This article is excerpted from Singing to the Plants: A Guide to Mestizo Shamanism in the Upper Amazon (University of New Mexico Press, 2009).

It is getting dark, and the room is lit only by a few candles. People are beginning to gather. They talk quietly in small groups, or lie in mute and solitary suffering on the floor. People tell jokes and exchange stories; they talk about their neighbors, about hunting conditions, about encounters with strange beings in the jungle. Some of them will drink ayahuasca, and some will not; some will drink for vision, and some for cleansing. Some drink in order to see the face of the envious and resentful enemy who has made them ill, or the one who has caused their business plans to fail, or the one with whom their spouse is secretly sleeping. Some drink to find lost objects, or see distant relatives, or find the answer to a question. Some may use la medicina as a purgative, a way to cleanse themselves. All are here for don Roberto to heal them.

Except for me. I am here not to be healed but rather to learn the medicine. I am here to be the student of el doctor, la planta maestra, la diosa, ayahuasca, the teacher, the goddess; to take the plant into my body, to give myself over to the teacher, to become the aprendiz of the plant, while under the powerful protection of don Roberto’s magical songs, his icaros. I have been following la dieta, the diet — no salt, no sugar, no sex, eating only plantains and pescaditos, little fish. I have drunk ayahuasca with don Roberto before, and with other mestizo healers around Iquitos — doña María, don Rómulo, don Antonio. I am nervous about the vomiting. I wonder what I will see tonight; I wonder if I will see anything.

Don Roberto comes into the room, moves from person to person, joking, smiling, asking about mutual acquaintances, gathering information, talking about matters of local interest, getting the stories of the sick. Some people laugh at a joke, feel the brief light of his full attention on them and their problems. He spends some time talking informally with each person who has come for healing, and often with accompanying family members, quietly gathering information about the patient’s problems, relationships, and attitudes. In addition, as himself a member of the community, don Roberto often has a shrewd idea of the tensions, stresses, and sicknesses with which the patient may be involved. There are about twenty people present. Everyone is given a seat and a plastic bucket, filled with a few inches of water, to vomit in….

Don Roberto then goes around the room, putting agua de florida cologne in cross patterns on the forehead, chest, and back of each participant, whistling a special icaro of protection called an arcana, and blowing mapacho smoke into the crown of the head and over the entire body of each participant. Don Roberto usually sings the same protective icaro at each ceremony. The song has no special name; don Roberto simply calls it la arcana.

The goal is to cleanse and protect, on several levels. The arcana calls in the protective genios, the spirits of thorny plants and fierce animals, and the spirits of birds — hawks, owls, trumpeters, screamers, macaws — which are used in sorcery and thus the ones who best protect against it. Moreover, the good spirits like — and evil spirits hate — the strong sweet smell of agua de florida and mapacho, which thus both cleanse and protect the body of the participant. The goal, as don Roberto puts it, is to erect a wall of protection “a thousand feet high and a thousand feet below the earth.”

Don Roberto sits quietly on a low bench behind his mesa, lights another mapacho cigarette, picks up the bottle of ayahuasca, and blows mapacho smoke over the liquid. He begins to whistle a tune — a soft breathy whistle, hardly more than a whisper — as he opens the bottle of ayahuasca and blows tobacco smoke into it. The ayahuasca, don Roberto says, tells him — in the resonating sound of his breath whistling in the bottle — which icaro he should sing, and he “follows the medicine.” The initially almost tuneless whistling takes on musical shape, becomes a softly whistled tune, and becomes the whispered words of an icaro, which may be different at different ceremonies.

When the icaro is finished, he whispers into the bottle the names of everyone present, adding “… and all the other brothers and sisters” if there are people present whose names he does not know or remember. Finally, he whistles softly once more into the bottle, the breathy whistle fading into his whispered song, his icaro de ayahuasca. He is jalando la medicina, calling in the medicine, summoning the spirit of ayahuasca.

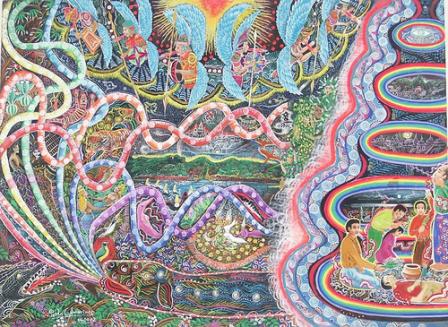

Image: Hondas de la Ayahuasca by Pablo Amaringo, courtesy of Howard G Charing on Flickr via Creative Commons license.