While the media in the U.S., Mexico and beyond often focuses on an inflated image of Santa Muerte as a so-called ‘narco-saint,’ her devotees come from a broad spectrum of those who have stepped beyond, or been pushed outside of, the status quo. She stands as a loving matron for those who accept lives lived in the liminal areas of social identity. As violence, economic disparity and often haphazard social engineering tear apart traditional boundaries, those left unattended by official support and recognition must seek solidarity within spiritual spaces that provide for their needs. In the Americas, Santa Muerte has come forward as a powerful patroness of those whose devotion occurs in the borderlands of social upheaval and her presence has become one of the most potent images of the drastic changes occurring in contemporary culture.

When we take a closer look at her position within the narco-culture we find that she does not appear here due to some preference for cartels or drug gangs, but rather because she does not judge those who come to her for help. At Dona Queta’s shrine in Tepito, a neighborhood that the media has branded as one of Mexico DF’s most notoriously violent, petitions are more often heard for health and well being than the media’s reports of ill repute would have us believe. Despite the image of Santa Muerte as a criminal saint, Dona Queta is often seen aggressively pushing away “fucking thieves” and those who seek to petition the Bony Lady for what she feels are untoward ends.

Introducing Tepito for a recent article, Judith Matloff, a Columbia University professor writing for Al Jazerra America, highlights how establishment media frames the social margins that Santa Muerte oversees:

“Even for many city residents, the neighborhood of Tepito is a no-go zone, 72 blocks of Latin America’s biggest black market, a labyrinth of stalls that serve as refuge and home for outcasts: drug dealers, pickpockets, transvestites, thieves and sellers of contraband.”

Here we have a strange incongruity, amid a list of those active in illegal activities Matloff includes transgender individuals, whose only ‘crime’ would be not fitting within a naive status quo vision of gender and sexuality. In creating this false association, however, the article gives us a key as to why Santa Muerte has become one of the fastest growing devotional traditions in the Americas. She vividly represents the growing disparity that exists not only on an economic level, but also on the level of social understanding between those who exist within the official comfort of privilege and those that exist outside of protection of mainstream institutions. In a very real way, she also represents the growing realization of the majority (for the dispossessed far outnumber the privileged few) forced to the margins by the establishment structure to say –

“We have no need of you, la Madrina, our Godmother, will take care of us.”

An academic article titled Devotional Crossings co-authored by Cymene Howe, Susanna Zaraysky, and Lois Ann Lorentzen shows a more nuanced sense for this in its discussion of transgender sex workers who migrate between Guadalajara and San Francisco, providing us with a deeper understanding of the ability that Santa Muerte has to reassert individual empowerment for those that are considered cast offs by the small percentage of those within the mediated norms of social privilege:

“Transgender sex workers, who feel ostracized or unwelcome attending church, respond to their spiritual needs by crafting their own devotional practices among themselves. These religious rites are eminently portable, and knowledge about them is shared among friends. While not necessarily sanctioned by the Church, these practices are sacrosanct to those who perform them. Religious practices in Mexico, as in many places, rotate around the repetition of particular rites: going to church every week, saying prayers, making pilgrimages to significant churches, shrines, and sites, and performing specific rituals at celebrations and for the saints’ holy days. Likewise, sex workers say their daily prayers, wear pendants and religious symbols, and construct altars to the Virgin of Guadalupe, St. Jude, and Santisima Muerte. Though the objects of their devotion may differ from those found in the churches of their childhoods, they nonetheless continue the practice of worship by maintaining a spiritual’ element of their lives and looking to each other for guidance on prayer and devotion.”

Yet, even here we are faced with the disturbing reality that gender and sexuality remain taboo subjects, where sex work and transgender identity find themselves conflated into an area of curiosity and marginality for scholarly inquiry. The piece is sensitive in its depiction, but still speaks to the fact that the cold eye of academia does not fully capture the very human relationships being put under the microscope.

Even though it is still largely under the radar in the United States, Santa Muerte’s tradition as it relates to the LGBT community in Mexico is illuminated by one of the largest public shrines in the U.S. A vibrant sacred space dedicated to La Flaca in Queens, New York is overseen by Arely Gonzalez, who, as a piece from Faith in the Five Burroughs explains, “is an immigrant and transsexual. In Mexico, she suffered discrimination and was kicked out of Catholic churches. In the U.S., she has become a leader in the community of devotees to Santa Muerte. Each August, she organizes a large celebration for her saint. This year, she expects over 500 attendees, and has already booked one of New York’s most prominent mariachi bands. Devotees at Arely’s celebration come from all walks of New York’s Latino immigrant community—proof that Santa Muerte’s reach has expanded.” Here we see that rather than illegality, Santa Muerte is a patroness to all of those who find themselves ostracized by official organizations, whether due to their marginal status as individuals pushed to the side by U.S. immigration policy, or those who have for one reason or another found themselves unsupported by the structures that are assumed to uphold our society.

One of the most nuanced Christian theologians of the 20th century, William Stringfellow, wrote extensively on the role of marginality in faith. For him, the powers and principalities mentioned in the Christian New Testament were the driving force behind society’s ills, yet his exposition of this fact goes far beyond the considerations of mainstream Evangelicals or Catholics, both of which he saw as themselves representations of demonic powers. In his book An Ethic for Christians and Other Aliens in a Strange Land, he observes that:

According to the Bible, the principalities are legion in species, number, variety and name. They are designated by such multifarious titles as powers, virtues, thrones, authorities, dominions, demons, princes, strongholds, lords, angels, gods, elements, spirits…

Terms that characterize are frequently used biblically in naming the principalities: “tempter,” “mocker,” “foul spirit,” “destroyer,” “adversary,” “the enemy.” And the privity of the principalities to the power of death incarnate is shown in mention of their agency to Beelzebub or Satan or the Devil or the Antichrist…

And if some of these seem quaint, transposed into contemporary language they lose quaintness and the principalities become recognizable and all too familiar: they include all institutions, all ideologies, all images, all movements, all causes, all corporations, all bureaucracies, all traditions, all methods and routines, all conglomerates, all races, all nations, all idols. Thus, the Pentagon or the Ford Motor Company or Harvard University or the Hudson Institute or Consolidated Edison or the Diners Club or the Olympics or the Methodist Church or the Teamsters Union are principalities. So are capitalism, Maoism, humanism, Mormonism, astrology, the Puritan work ethic, science and scientism, white supremacy, patriotism, plus many, many more—sports, sex, any profession or discipline, technology, money, the family—beyond any prospect of full enumeration. The principalities and powers are legion.

He continues with:

“Corporations and nations and other demonic powers restrict, control, and consume human life or order to sustain and extend and prosper their own survival.

…

The principalities have great resilience; the death game which they play continues, adapting its means of dominating human beings to the sole morality which governs all demonic powers so long as they exist–survival.”

No stranger to the realities of these powers and principalities, Stringfellow himself was a civil defense lawyer in Harlem during the Civil Rights era. His theological ideas come directly from his involvement with the struggles of those marginalized by the system who were caught in the midst of social systems they had no power to change or defend themselves against. Within this matrix Stringfellow identifies the source of this demonic power as death itself, as he puts it:

“[H]istory discloses that the actual meaning of such human idolatry of nations, institutions, or other principalities is death. Death is the only moral significance that a principality proffers human beings. That is to say, whatever intrinsic moral power is embodied in a principality—for a great corporation, profit, for example; or for a nation, hegemony; or for an ideology, conformity—that is sooner or later suspended by the greater moral power of death. Corporations die. Nations die. Ideologies die. Death survives them all. Death is—apart from God—the greatest moral power in this world, outlasting and subduing all other powers no matter how marvelous they may seem for the time being. This means, theologically speaking, that the object of allegiance and servitude, the real idol secreted within all idolatries, the power above all principalities and powers—the idol of all idols—is death.”

It is important to reflect on these ideas here, in the context of Santisima Muerte, or Most Holy Death, and of Santa Muerte, Saint Death, for in her emergence as a prolific and potent patroness in the Americas she represents a very real enemy to the power of death as a negative force. Perhaps more than any other theological exploration of Christianity, Stringfellow’s work provides a very direct context for seeing the threat that Santa Muerte poses to the current social structure, and gives insight into why mainstream media, orthodoxies and officials all react with such disgust and abhorence to her presence in the world.

Transgender issues arise from the same conflict of control, where the abandonment of gender norms takes away a very powerful weapon for maintaining the status quo which privileges those who identify with normative gender distinctions. This is why a piece like Judith Matloff’s in Al Jazeera America places transgender individuals in a list related to criminality, the crime being breaking down the barriers of social control. Highlighting graffiti that says “Tepito Exists Because It Resists,” the article admits that the discomfort here is based on a lack of official order within the space. In this light it is interesting to see that the powerful matrons of the community, the ‘Cabronas’ mentioned in the piece, are also placed within this criminalized marginality.

All areas of liminal resistance represent a breach in the world order, for better or worse, and those forces in place to maintain that order react with varying levels of violence towards anything that threatens their position, transgender individuals, strong women, heterodox devotional traditions and anything that unveils the illusion of normalcy through which the powers that be maintain their control.

“If the world hate you, ye know that it hated me before it hated you. If ye were of the world, the world would love his own: but because ye are not of the world, but I have chosen you out of the world, therefore the world hateth you. Remember the word that I said unto you, The servant is not greater than his lord. If they have persecuted me, they will also persecute you; if they have kept my saying, they will keep yours also. But all these things will they do unto you for my name’s sake, because they know not him that sent me.”

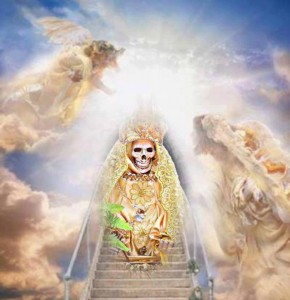

Standing over those demonized by the establishment she holds the scales of justice in one hand, and the scythe of judgement in the other. Those who would bring her children peace she smiles upon, for those who bring violence she bears a grimace. Her face a skull, her eyes empty, she can only be petitioned by the true heart of those that fall beneath her power. As death, this includes every living creature. How fearsome she must seem to those who have something to hide and to those who haven’t found the freedom of true devotion in the borderlands beyond the safety of the status quo.

Note: The quotes taken from William Stringfellow’s An Ethic for Christians and Other Strangers in a Strange Land were taken from a post on Experimental Theology blog.

Special thanks to the beautiful Santa Muertista community on Facebook for the images included in this article.

Interested in learning more about Santa Muerte? Check out SkeletonSaint.com a new collaborative project with Dr. R. Andrew Chesnut, Chair of Catholic Studies at Virginia Commonwealth University, and author of Devoted to Death: Santa Muerte, the Skeleton Saint