Ptolemy Tompkins is New Age royalty. The son of bestselling author and explorer Peter Tompkins – the man who taught us to talk to plants, search for Atlantis, and probe the inner meaning of the pyramids – Ptolemy is an acclaimed writer who produced Paradise Fever, his influential memoir of growing up in the ferment of New Age culture. He has written probingly on Mesoamerican spirituality, the mysticism of nature, and, more recently, the question of extra-physical survival. Ptolemy collaborated with Eben Alexander, M.D., on the mega-seller Proof of Heaven, and this past February Ptolemy published his Proof of Angels.

He does not document these topics in a sensationalized, psychic-friends-network kind of way. Rather, he brings deep intellectual seriousness to his subjects and pushes mainstream detractors to defend (and reexamine) their conviction that life is solely material.

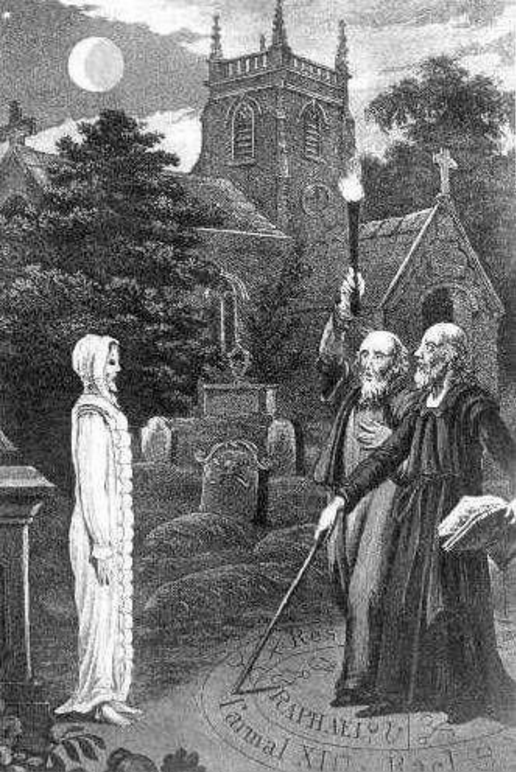

Ptolemy joins me on the evening of Wednesday, April 6th, for our latest Morbid ACADEMY dialogue, Tales from the Crypt, at Brooklyn’s Morbid Anatomy Museum. Here, in a preview of our talk, I ask him about the reality of heaven and hell, how to verify life after death, and the spiritual practice of underlining things in books.

- Is heaven real?

Yes. The big problem in our culture is that we have to ask the question to begin with. Not that asking questions is bad, but heaven should be such a core intuition that the notion of asking whether it’s real should appear ridiculous. If there’s an uncertainty about the existence of a larger dimension that contains and sustains our core being, and if that uncertainty manages to thoroughly penetrate and infect us, so that we go around constantly with the nagging, and terrifying, notion that when we die we simply cease to exist, it affects every aspect of our lives. So many esoteric traditions point to a time before this happened – when the physical environment was felt, was concretely experienced, to exist within a larger, spiritual domain. Then, for one reason or another, we lost that certainty, and became stuck in the physical world, desperate little ghosts trapped in our material brains, with nothing out beyond us but other poor saps, stuck in their own brains, and destined, like us, to extinction once those brains stopped functioning. “Heaven” is, of course, a word that’s been trampled to pieces. It’s hard to use it and have anyone – even people open to spiritual matters – take it seriously. It has a nudge and a wink attached to it; which is too bad, because it really is a beautiful sounding word.

- If there’s a heaven or an afterlife, is there a hell?

This larger, spiritual domain that peoples before us experienced as vivid realities typically contained an “up” and a “down” element. There were infernal regions, and these were often seen not as domains of punishment but of harrowing and purification. You passed through them, got the bad stuff burnt out of you, and then moved up. Of course, the question of what this means from our modern perspective, of whether this cleansing was genuinely ethical in a way we would understand, or more ritualistic and in line with the established (and sometimes memorized) rules and regulations of the culture in question … That gets mighty complex. Certainly complex enough that I don’t even remotely have a grasp on all the literature, both esoteric and academic, that discusses this question. But all that literature, all that scholarship, valuable as it is, shouldn’t drown out the basic, fascinating fact of the universality of this intuition: that physical life, the life we are all stumbling through, exists within the context of a larger geography, some parts of which are terrifying, but which in its higher regions contains the fulfillment of all our desires, the wholeness that we constantly intuit we are lacking, down here in the “middle” section of physical embodiment.

- How do you respond to critics who say near-death experiences (NDEs) are more or less dreams?

What the hell is a dream? It’s a (for most of us) muddied and confused continuation of the consciousness that we at all points are, that we never lose even at the deepest and most (seemingly) unconscious levels of sleep. “Consciousness” is another one of those totally trampled words. Yet, like “heaven,” it’s a word we need. Everyone knows what it is to be conscious, but of course no one can define it. The Eastern traditions tell us (I’m generalizing of course) that consciousness is eternal and indestructible, that it is our ever-present connection with Divinity, the place where we overlap with God, Brahma, whatever you want to call it. The Western traditions say the same thing, though they tend to do so in a more underground fashion, and with a greater focus on the durability and reality of individual, personal consciousness. (More generalizing, of course.) NDEs are dreams, but so is physical life, and so is the life that waits beyond the death of the body, if we take “dream” to mean a situation of consciousness in which the experiencer is partially experiencing, and partially creating, what he or she experiences. Typically, when someone objects that NDEs are “just” dreams, what they are really saying is that dreams, like ordinary daily consciousness, are both (here’s another over-used word) epiphenomenal in nature. Waking and dreaming consciousness is just steam rising off the physical brain – something evanescent and basically unreal. But what if our inner conscious awareness is actually the real thing, and physical reality, that dull business we encounter when our eyes flutter open in the morning, is in essence no less “dream-like,” no less insubstantial, than the crazy stuff we were experiencing just before our eyes opened? I’m saying nothing new here. You could hear Alan Watts or Aldous Huxley rattle off that same basic argument. But I think it’s the best way to respond to the materialistically minded person who might choose to proclaim the fantastically vivid descriptions of higher (and lower) regions of existence brought back by NDE-ers as “just” dreams. It’s a non-argument.

- What is the single most persuasive piece of evidence you’ve found for life after death?

There are books, certain books, that when reading them have shifted my consciousness into a zone in which the continuation of life beyond the death of the physical body became a fact, simple and almost laughably obvious. Books are, among other things, remarkable spiritual tools. I think it was the author Marilyn Robinson who said that there’s nothing more human than a book. For me, there have been no tools of access to realms of certainty above and beyond mundane life more powerful than certain books. Jane Sherwood’s The Country Beyond. Owen Barfield’s Unancestral Voice. Valentin Tomberg’s Meditations on the Tarot. Certain poems by the Swedish Poet Tomas Tranströmer….Passages by these authors haven’t taken me up and beyond, but they’ve momentarily unlocked those certainties that I carry, deep within me, of the reality of that larger landscape and my place within it. I realize: Jesus, I KNOW this stuff already. Then – boom! – I shut the book, get up to do the Sunday chores, and it’s gone. The gates swing closed again. But it was there, that certainty, and I think if you manage to get this kind of glimpse enough times as an adult, it weakens – terminally – all the arguments coming from this level of experience that there is nothing more beyond, and nothing real about the descriptions people have brought back. I think – I’m not sure, but I think – the talking about an experience that a lot of people out there have had, this business of getting a momentary experience of total grounded certainty about the reality of the worlds beyond. The task, it seems to me, is to find a way to keep that certainty alive, and to build it, so that it doesn’t always vanish when the book shuts, or when one gets up from meditation, or the drug wears off, or whatever else it is that brought it on. States of consciousness shift in an instant. One second we have it, the next second we’ve lost it. That’s the way it works down here, as far as I can see, at least for most of us.

- How has your research personally changed you?

It has allowed me to keep those moments of positive, intuitive connection to the fact of that larger landscape going for longer and longer periods. It has grounded me more in the certainty of that life, my life, won’t come to a stop at death, just as the world, the real world, doesn’t come to a stop with the physical. I’m no mystic, and when it comes to spiritual exercises of any kind I’m pretty lame, too. I used to worry about this. “I should meditate.” “I should go to church.” “I should go down to South America and take a bunch of ayahuasca.” And so forth. One day I read a line in a Joseph Campbell interview. I’m paraphrasing, but basically the interviewer asked Campbell if he had a particular spiritual practice he did regularly. Campbell said he underlined books. I thought that was so great. There are a million ways of getting into contact with the larger reality, with accessing that inner certainty that there is more, that we’ve been around longer than we think we have, and that we’re on our way somewhere as well. Any activity that increases this awareness, that helps to recover this lost but crucial certainty and shore it up so that bit by bit it lasts longer and longer, is a spiritual practice. Or at least I think so. Then again, maybe I’m just trying to rationalize the fact that I’m too lazy to meditate.

***

Join Mitch Horowitz and Ptolemy Tompkins on Wednesday, April 6th at 7 p.m. for Morbid ACADEMY Presents: Tales From the Crypt at Morbid Anatomy Museum in Brooklyn.