Between the real and its representation is an unseen world that photographer Shannon Taggart has learned to capture with her camera. Shannon is the true medium, channeling the phenomena of belief and its manifestations. Casting herself deep into the culture of spiritualism, Shannon’s work is reminiscent of people like the ethnobotanist Dr. Richard Evans Schultes who studied the ritual use of hallucinogenic plants by indigenous cultures by not only living among them, but participating in their rites. Shannon is an anthropologist of the spirit world, documenting the precarious nature of belief, while allowing for chance, accident, and error to shape whatever truth might emerge. In 2017, we suffer from a demythologizing that is rendering our lives empty and cynical. Shannon’s photographs are a deliberate re-enchantment of the world.

Shannon has launched an Unbound campaign to support her new book SÉANCE: Spiritualist Ritual and the Search for Ectoplasm. She describes the book a work that “seeks to amplify the reflexive relationship between Spiritualism and photography and to explore the ideological, material, geographical, historical and metaphysical correspondences between the two.” Shannon and I corresponded over email about her work, the new book, and how sometimes the most authentic experiences are those that inhabit the liminal.

Looking at your photos recently I was reminded of musician and composer Kim Cascone’s “Errormancy” where he writes: “In the hands of the right artist, a glitch can form a brief rupture in the space-time continuum, shuffling the psychic space of the observer, allowing the artist to establish a direct link with the supernal realm.” Do you see you work as corresponding to this idea of accident and chance?

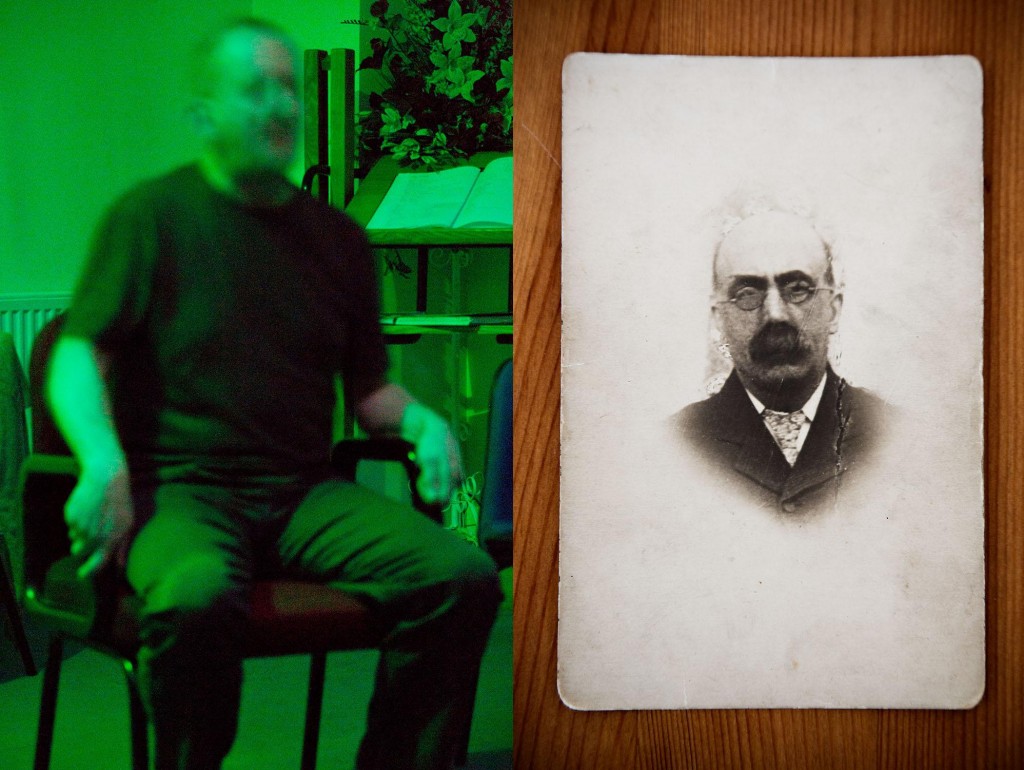

Yes. I became inspired to experiment with the photographic process after some happy accidents happened with my camera. When I embraced chance and error, it felt as if I had opened a door to someplace else. I began to use photographic artifacts and messy conventions like blur, motion, and flare. These unpredictable elements rendered the invisible exchanges between mediums and spirits in unforeseeable ways. In this play with the process, my camera handed over some striking synchronicities. The resulting images consider the conjuring power of photography itself.

One example happened during a trance demonstration with the English medium Gordon Garforth. I documented Gordon in the depths of a mediumistic state, using long exposures. In every image I made, he looked very different. I was afraid to show him one of the pictures which oddly seemed to depict him with Hitleresque facial hair on his clean-shaven face. Gordon loved the image, saying it perfectly revealed what he referred to as his “ectoplasmic masks.” He then took me to his home to see a photograph of his Great-Grandfather, who wore the exact same mustache.

Why do you think the camera can capture the ineffable in way that the eye alone cannot?

Photographs are bizarre slices of reality. Light and time are its raw materials. They render three-dimensional space compressed, flat and silent. I like to think of photographs as layered manipulations. It is also interesting to consider that a photographer’s conscious attention embeds itself within the frame. There’s almost a telepathic element of communication that comes through in the work of great photographers. I don’t know if photography can actually capture the ineffable, but it can refer to it, or resonate with it.

So we are really talking about art and its ability to communicate something that is often impossible to capture accurately. In avoiding the literal, it appears you are not trying to “prove” spirits exist.

Exactly. I am not trying to prove or disprove anything. I am trying to delve into the mystery of both Spiritualism and photography. I am seeking to amplify ambiguity. I purposely try to blur the line between cause and effect and to confuse the point where one technique stops and the other begins, like a feedback loop. I strive to make pictures that use photography’s own mechanisms to question these spiritual experiences. I am interested in images that contain both mechanical and spiritual explanations, requiring an interpretation to be made by the viewer.

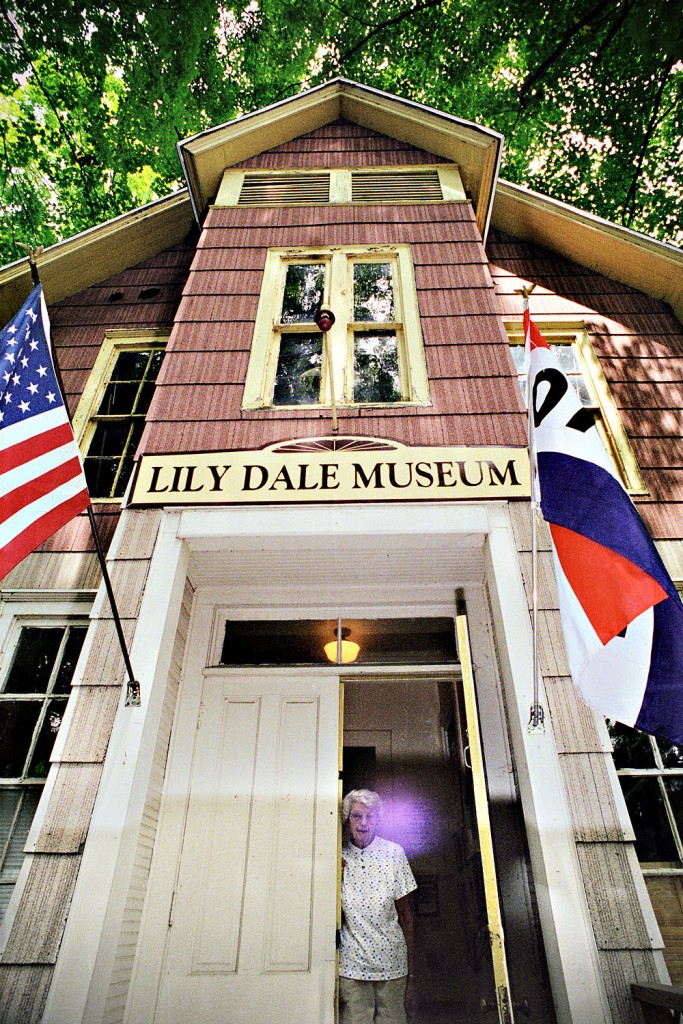

Your new book focuses quite a bit on Lily Dale, the Spiritualist community in upstate New York. These are folks that tend to believe wholeheartedly in the existence of spirits and our ability to communicate with them. How did you get them to trust you, given your own mercurial stand on these ideas?

The friends I have photographed in Lily Dale welcomed me in because they knew I was sincerely interested in learning about their religion. Spiritualists believe in communication with spirits of the dead, but they do not preach a doctrine to others. The Spiritualists I know invite questions and encourage visitors or clients to be discerning. And, there is plenty of room in Lily Dale for a variety of viewpoints, which is one of the reasons why I love the town so much.

Have you ever had an experience at Lily Dale or with medium that your photo after the fact felt lacking somehow?

Yes, particularly while photographing mental mediumship. I’ve witnessed profound moments that were wrought with emotion and intensity that ended up looking very boring when photographed. I’ve also taken pictures of mundane situations that became something phenomenal through the camera’s mechanism. Photography creates its own reality.

Your ectoplasm photos are the more “literal” than others insofar as they are capturing supposed supernatural phenomena at play. Can you tell me about the experience of seeing and then photographing this kind of physical mediumship?

Witnessing ectoplasm in real life was a surreal experience, like watching vintage spirit photographs jump to life right before my eyes. During the ectoplasm séances I tried to make pictures that were as straightforward as possible, because the spiritual had already been fully realized and made visible through the performative action of the medium. I felt there was nothing to do other than to carefully document the ectoplasmic event.

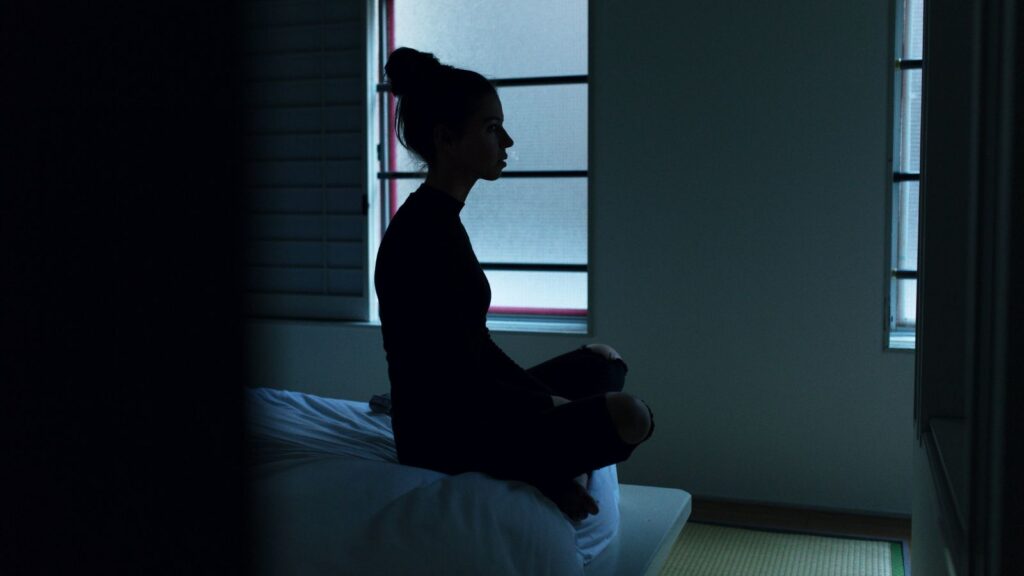

Some of your other work documents Vodou ceremonies in New York. What is about people in states of spiritual trances that you find so evocative?

I’ve always been interested in psychological space, and also in photographs that somehow manage to speak to its presence. In religious ritual–when reality blurs and mysterious shifts in the psyche occurs– I find myself fascinated and very drawn to make photographs.

One example of this happened while photographing a woman I knew during a Guédé vodou ceremony in Brooklyn. I had seen possession before, but never so close. Mambo Carmen’s eyes flickered, then reopened, seemingly free of her. Her body was wrapped, covered in powdered and then presented to the room. We were called to greet this god, Baron Samedi–the kingpin Loa of the dead. Someone ushered me over, and I picked up her heavy arms and danced the crisscross salutation over her body, the whole time searching for the Mambo Carmen I knew within her blank stare. A feeling rushed over me that I was actually in the presence of this archetype. I became so excited by this thought that I accidentally dug my fingernails deep into her hands. She did not flinch.

Magic, both in its stage and spiritual forms, is performative. It requires in both cases an element of trickery (tricking the mind as it were), insofar as we have to suspend disbelief to allow ourselves to be transformed. Do you use tricks in this way?

I embrace the camera’s ability to trick or fool. Crossing the boundary of what is considered unprofessional in the practice of photography–playing with uncontrollable elements like motion blur, lens distortion, light leaks, flare–feels magical to me. Giving control over to the process and seeing how the camera can render events differently from the way the eye sees is fascinating. It’s exciting to be shocked by your own photographs.

Why are we often afraid to live in this liminal place when it comes to the occult and the supernatural? There is tendency to either dismiss these experiences and ideas completely, or to accept them without reservation.

Liminal space (the threshold between two opposites) can be unsettling, chaotic and destabilizing. Betwixt-between states can bring about dramatic shifts or sudden change. For some, ambiguous positions are uncomfortable. There is a feeling of stability that comes with a solid viewpoint or a definitive answer. This question also brings to mind George P. Hansen’s masterful work The Trickster and the Paranormal, an epic resource that directly addresses the inherent mystery of the liminal realm.

Can a photograph alter consciousness?

Photography can create shifts in a person’s emotional state or point of view, and this is why it is such an effective means of communication. Photography also has metaphysical ramifications. It’s ability to trap time, freeze the reflection and preserve a person’s disembodied presence blurs the line between life and death, and allows a type of time travel to occur. Photographs invite you into a space that only exists within its frame.

Where do you place yourself, if at all, in the tradition of spirit photography?

Spiritualism’s photographic past contains some of the most bizarre, absurd, and uniquely unsettling images in the history of photography. My work builds on this strange record, which has been a resource and an inspiration to me. My book is an attempt at a next chapter.