I first heard about San Pedro de Casta because the village is the access

point for Marcahuasi, an allegedly ancient archeological site high in the arid

western slopes of the Peruvian Andes. Here, people claimed, humans had

lived for 10,000 years and left behind sculptures that depicted the various

races of humanity and a wealth of other oddities.

My discovery of the village’s existence happened at a peculiar spot in Lima

in the mid 1970s. I was in one of the downtown tourist shops near Plaza

San Martin, looking for an ancient jungle weaving that I had heard may have

been for sale in one of the boutiques. Such weavings were purported to represent

an old language that used mathematical symbols, developed by an antediluvian

culture that thought in mathematical terms, unlike our present cultures that

express language with phonetic and pictographic alphabets.

A foreign woman in the store, dressed in a lavishly beaded dress with

bangles on her arms and layers of silver necklaces covering her bosom, inquired

as to my mission. I politely explained

my interest in ancient Peru and she quickly asked if I knew about

Marcahuasi. I did not, so she gave

me basic facts. The site was located on a plateau about three thousand three

hundred meters above sea level yet only eighty kilometers from Lima, a day hike

above the village of San Pedro de Casta.

Marcahuasi was held sacred by many indigenous groups and apparently contained

an unparalleled set of ruins, including depictions of all the major human races

and much, much more. Getting there would present a challenge, she went on, but

the rewards were worth the effort.

During the 1970s public transport was spotty in many different regions of

Peru. I already knew this. So, how was one supposed to get to San

Pedro? The only option, my new friend explained, was to take an early

morning bus from the squalid market area near Plaza San Martin in downtown

Lima, head for the resort town of Santa Eulalia, and then hitchhike along the

road to Huancayo, debark at the fork that led straight up the side of a steep valley to San Pedro, and stick

my thumb out for that segment, too.

I soon arranged to visit San Pedro with an English friend, Michael. I had further business in Lima for the

next couple of days so we agreed to meet in San Pedro in a week’s time.

He would make the trip first, procure accommodations, and we would hike

together to up the mountain to Marcahuasi.

He departed two days before I did. Early in the morning I decamped

from a modest hotel to the marketplace bus stop, my head dizzy from an all night

rap session with a young Australian female acquaintance. I am quite sure

we solved all the world’s problems that evening, but come morning our brilliant

ideas had disappeared with the rise of the mist-laden Pacific sun.

I made my way to the proper bus and boarded. The vehicle, an old and

rickety American Bluebird, was packed with local campesinos. The

only available seat was a spot at the rear on the vehicle’s floor and I sat

there, making a cushion from my pack.

The bus departed in due time and made its way through the barrios

jovenes that ringed the city. But soon we began to climb from the

coastal desert; the sun appeared as we gained altitude, leaving the seaside garua

fog below. I was happy to get away from Lima. One grows weary of

the endless traveler babble sessions in the hotels there, and the empty

promises, made during furious mental marathons, for working out great world

changes. Yet here was a promise I had kept, perhaps more simple than

most, but still, I was on my way to a remote village to meet Michael and hike

to one of the most controversial archeological sites in South America.

What could go wrong?

The

first trouble arrived unexpectedly at a police checkpoint, twenty kilometers

from Lima. Officers boarded the bus and began to shout at the passengers,

demanding identification and other proof of their right to travel. The

burly men, dressed in ill-fitting uniforms and who handled their assault

weapons with sloppy indifference, soon tired of questioning the Peruvian

travelers and spotted me, a lone gringo with a British army surplus field pack,

surrounded by other meager possession in the back of the bus. “Get up here

and off the bus!” they barked. I complied with haste. Once

outside the old school bus, they noticed a plastic baggie hanging from my shirt

pocket. “What do you have in there? Show us!” I

produced the bag, which contained Dutch Drum tobacco. “That’s

marijuana! ¡Vamos a la comisaría!” So I tagged after them

into a one-room adobe shack by the roadside. Indoors, they rifled my

belongings and found another baggie, this one filled with white powder.

“¡Cocaina!” they cried. “You are under arrest.”

By now I had tired of the harassment. First, I rolled a cigarette, lit

the thing and blew smoke in their faces. “See, this is tobacco, not

marijuana.” They were skeptical but couldn’t deny the smell.

Then I took off a shoe and thrust my foot on the desk of the commandante.

“Look, I have athlete’s foot. The white powder is sulfathiazole,

which helps alleviate the symptoms. Here, put it up to your nose but

don’t inhale. It’s toxic if taken internally.” The cops did

not believe this story but I showed them an empty packet of the drug from my

pants pocket to prove the substance’s provenance. I stated, “I am a

tourist who has come to see your beautiful country and to help foster

understanding between your citizens and ours. How dare you accuse me of

being a criminal?”

With that comment they relented and returned my plastic bags — the bag of

white powder was in fact cocaine — and reluctantly gave me permission to

board the bus. Luckily the driver had waited to see the outcome of my

interrogation. The passengers burst into applause when I climbed the

stairs. Score one for the good guys!

The bus trip ended as advertised in Santa Eulalia. This was a quaint

town with many restaurants and river-side pensións, where limeños

with sufficient means spent weekends away from the polluted streets of their

home city. Otherwise the place had little to recommend it. So I

stuck out my hand and flagged a passing truck. The driver was headed to

Huancayo and he let me off at the intersection of the track that led up the

hills toward San Pedro de Casta. I began to talk with a few men who were

standing nearby. They asked me what the heck I was doing here, so I explained the

reason for my journey. One of them was about to walk up the mountain to

San Pedro, and he invited me to accompany him. By walk, I mean that he was

planning to trek some 7000 vertical feet uphill on a barely-negotiable path.

I declined.

No other traffic passed by that day, so I pitched my tent by the river,

behind some trees to keep out of sight, and spent a restless night listening to

the flow of the current and to all manner of unidentifiable noises. The cocaine I had carried for

companionship evaporated in the humidity of the night and left me feeling lost

and forlorn.

The next morning, feeling stressed, tired, and hungry, I managed to secure a

ride on a truck that was going to a town near San Pedro. The driver, who held

a bottle of aguardiente in one hand and a bag of coca leaves in the other,

appeared ready to set a land speed record for mountain travel. By now I

was too burnt-out to care, so I jumped into his cab and we took off, tires

screeching in the dirt.

The road climbed the mountain in a series of zigzags.

At every hairpin turn the driver, after helping himself to a nice belt of

moonshine, fishtailed around the corner, coming within inches of falling off

the road and thousands of feet to the valley floor below. Then he would

turn to me and grin, the wad of coca leaves in his mouth showing a bright green

tint on his teeth. Only fatigue prevented me from having a nervous

breakdown.

He finally let me off at another intersection, where I saw the village of

San Pedro, perhaps an additional six kilometers distant. The view was

magnificent. But I had a long uphill walk ahead of me, with no prospect

of any vehicular traffic with which to hitch a ride.

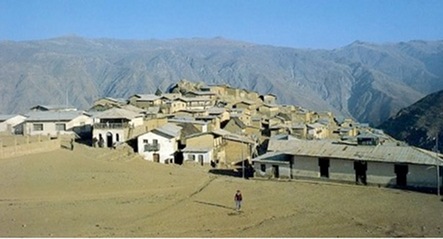

San Pedro village perched on its mountaintop location, as seen from

my drop-off point. A lot further away than it looked.

I reached the village just before nightfall. The town was small, so small

that my Brit friend saw my approach an hour before my arrival. “You

made it!” he exclaimed. “Did you bring any food?”

“Food,” I replied weakly. “Why would I do

that?” “They don’t really have any here,” he said.

Oh boy. That was great news. “Do we have a place to stay?”

I asked.

“Yes. They gave us a house.” Sure enough, Michael

led me to a one-room hovel with a dirt floor and a pile of unidentifiable offal

in the corner. No furniture, no electricity, just a front door, with a

thatched roof to complete its list of charms. “How much do we have

to pay?” “Nothing, they gave it to us for free and said we can

hang out as long as we like. They

don’t have any money here and so they don’t have any use for cash.”

“Where’s the outhouse?” I said. Michael shrugged. “They

don’t have loos, either. You go out back into the fields to shit or

whatever.” By now he could have told me that we were required to

take our dumps in front of the town council every morning and I wouldn’t have

cared.

“Hey,” Michael now informed me. “Know what? The hillsides are

covered with San Pedro cactus. There’s mescaline everywhere growing wild.

When we go up to Marcahuasi we can take a batch.”

“Whatever,” I said, only wanting to unroll my sleeping bag and get

some rest.

We lingered in the village for a few days gathering information about

Marcahuasi and related subjects. The locals had seldom seen outsiders —

we were there before the place became a New-Age pilgrimage focal point — and so

they were delighted to share their knowledge and experiences.

First, the village was a hot spot for UFO activity. Night after night

strange lights appeared in the sky and on at least one occasion a saucer had

dive-bombed the town. The Catholic priest, who did not want to hear such

nonsense, told the villagers that these sightings were devil’s work, causing

the townspeople to promptly kick out the priest and close the church.

This was nearly the only place in Latin America where I’d ever heard of the

Church in modern times being run out of town.

Old men told us of cave entrances that could only be seen by moonlight at

certain phases of its orbit around the Earth. What was inside these

caves? I wanted to know. Entrada gratis pero no hay salida, came

the invariable answer. In other words, you can check it out but you can’t

leave. Don Henley and Glenn Frey would have appreciated the sentiment.

One afternoon I asked the villagers why they no longer dressed in

traditional clothes. The hamlet was laid out in its original pre-Hispanic

street grid and clearly the modern world had yet to intervene. They

replied that in recent times, people had dressed the same as their forefathers,

but this was no longer the case. Their castaway rags of Western clothing

belied the sadness behind these remarks.

As for Marcahuasi, they believed fervently that the site was special, and

had been settled long ago by an unknown civilization. Go visit for

yourselves, they said. You’ll see what we mean.

At last Michael and I made the necessary preparations and hiked to

Marcahuasi. The mountain’s summit formed a plateau a thousand meters

above San Pedro, with ravines and deep valleys cutting into the arid landscape.

We took sleeping bags, food, and mescaline, but didn’t bother with my tent, hoping

to save weight during the hike.

Well, we explored Marcahuasi after spending a frigid night camped under the

stars. The Milky Way shone like a giant headlamp crossing the night sky,

and strange lights buzzed back and forth between the stars until dawn. As

to their nature I cannot say, except that these odd lights moved in non-linear

fashion and did not behave like any airplanes or satellites I have ever seen.

We saw the famous “Monument to Humanity” as it is sometimes

referred to, a rock that is supposed to depict different human races from

selective angles. We walked around it countless times. I believe

that this formation is a natural structure, and any human shapes that appear

are the result of our brains’ tendency to form pattern recognitions in

otherwise random features. I

formed the same impression when examining more of the “statuaries.” At this altitude, with the extreme

temperatures caused by the equatorial sun followed by inevitably clear nights,

rocks eroded in peculiar fashions, chunks falling in sheer lines almost as if

carved, due to moisture expanding in pre-existing fissures.

We brewed several pots of San Pedro; I had been taught how to do so in

Vilcabamba, Ecuador, home to South America’s most potent variety of the drug. But the substance chose to show us

nothing we couldn’t see with our own eyes. Its properties had no power over the energies of Marcahuasi;

this was a site meant to be experienced by humans using their own

divine-inspired senses. That the

plateau held answers to some of humankind’s riddles was clear, but it was up to

us to understand the answers. We

were left, as humans so often are, to rely on our natural devices. Michael and

I reached the same conclusions independently: the story of the Marcahuasi civilization

dates from such ancient times that modern academic attempts to try to pinpoint

its beginnings constitute an exercise in egotistical foolery.

And we did see ruins, lots of them. Mostly low stone structures that

had been built as mausoleums. Crawling into one I saw skulls, clay pots,

jewelry and other offerings, but did not touch the objects out of respect for

the ancient peoples who had placed them there.

In due time we returned to San Pedro, staying in our hovel a few more days

and making more friends whom I would return again to visit in later

years. These were the nicest people, poor in the extreme, but happy to

share whatever they had without asking for money or anything else in return.

We did experience hunger most of the time, but the villagers had enough potatoes

on hand to keep our bodies functioning.

When told of the tombs we had discovered, the elders nodded their heads

solemnly. “You were respectful,”

one old man allowed.

“What would have happened if we had tried to remove something? I said.

The man moved a finger in a silent horizontal motion across his throat. “We guard these places always,” he

finished.

When we departed San Pedro for the long walk back to the road and the modern

world, we bade goodbye with reluctance. As well as saying farewell to

some amazing people, we understood also we were saluting a way of life that was

vanishing in real-time. With every

visit I made during ensuing years the people had become more jaded, less

hospitable, and more anxious to collect the copious but well-intentioned

tourist cash.

Nowadays every UFO freak and New Age adherent includes San Pedro in their

Peru itineraries, and you can even travel there with groups. I have even

heard of tourists taking ayahuasca at Marcahuasi, a practice that makes as much

sense as dropping acid in a junior college remedial English class.

True, the local population now has money and the means to enjoy modern

consumer conveniences. But at what

price? The old ways are

gone. You can check it out but regrettably you can now leave.

All photos are by the author.