Nothing against Barak Obama, but we'd be mistaken to consider his politics a complete break from the past, a renaissance in participatory government, or the realization of an Internet-enabled "open source" democracy. He's pretty damn good, don't get me wrong, and he may just represent the closest thing yet to a GenX, post-boomer, anti-sentimental and a-mythic candidate for president. But there are a few ways in which his candidacy also reinforces some of the branded, celebrity-based, and charismatic techniques of traditional politics. To make the most of his candidacy and, hopefully, his presidency, we'll have to distinguish one from the other.

When Obama was first emerging into national awareness, he showed both promise and predictability. I watched his speech to the Democratic Convention in 2004, and saw pretty much what the Democratic party wanted me to see: a hopeful young politician who appealed to people beyond their classic demographic divisions. He spoke of a "one America" beyond blue-state/red-state classifications. Like Mario Cuomo's convention keynote speech of a decade earlier, he cast the Democratic Party as the party of higher ideals, greater compassion, and a more united people.

Obama's speech was also calculated, however, to neutralize the "hot-button" politics of the right. Karl Rove and other right-wing strategists had by then almost perfected the technique of micro-casting specific, emotionally charged messages to the people whom they wanted to hear them. Their direct mail experts sent letters to fundamentalists explaining that John Kerry wanted to make the Bible illegal. They sent others to southerners who owned pickups threatening the banning of the Confederate flag. This inspired many of them to hold protests side-by-side with white supremacists and Nazis.

If the Republican party would be the party of divisions, the Democrats would – at least officially – be the party of unification. The less factions saw themselves as special interests in competition with one another, the less those emotionally charged, hot-button issues could be made to work. The Democratic party would be about transcending division, while the Republicans could keep fighting in the gutter. Problem was, at least in '04, most of America was still angry and desperate enough to choose division and self-interest over any other possibility.

The primary season pitted unifiers against factionalists again – so far, with different results. While Huckabee ran for the religious right and Romney ran for the wealthy conservatives, McCain ran as a guy with ideas he thinks are good for the country. Although not explicitly a unifier, he's not particularly tied to any of the special interests that make for good hot-button politics. That's why the conservatives hate him: he's not strong enough on abortion or gun control or Jesus for them to make convincing and polarizing arguments over these issues. In if they're not sufficiently activated, the crazies may just stay home.

Hillary Clinton, meanwhile, ran a similarly divisive campaign against Obama. It's probably why the two of them ended up surviving the longest: she best represented the politics of splinter demographics, while he best represented the ethos of united-we-stand. While Clinton broke down the party into Hispanics, whites-who-really-work, and even caucus vs. primary states, Obama sought to address everyone at once. Clinton most effectively thwarted Obama by recasting the electorate as a set of separate tribes with mutually exclusive goals.

Her argument for maintaining this stance was that the real world is a combative and terrible place. In a dog-eat-dog world, only a mean dog can lead. This is why she ended up selling herself as a "fighter." She would fight against Obama and the Republicans, and thus prove her ability to fight against the bad guys out there in the Arab countries or even Europe.

That Obama represents an alternative to this divisive, target-marketed pandering is certainly a step in a great direction. That the American electorate is capable of seriously considering him as a viable candidate and leader is a leap in the same one. Both McCain and Clinton pose "you're either with us or against us" dualities. McCain does it because he's promoting a neoconservative ideology dependent on simple black and white dichotomies. Clinton did it in a cynical effort to pander to the people she believes are stupid and angry enough to respond to divisive, faux-populist rhetoric.

Obama alone (well, actually he, Kucinich, and Biden) presents a more complex understanding of the challenges facing America. It's a "GenX" sensibility, really, that depends less on emotionality and choosing sides than on a post-ideological clarity, and an ability to embrace seeming paradoxes. One can disagree with certain things Reverend Wright says while still embracing his message and influence. To the post-boomer audience, this is not weakness but strength. The alternative, as outlined by right-wing extremists such as Sean Hannity, is that candidate Obama Hussein secretly agrees with Wright, Farrakhan, and black militants which is why he cannot condemn the preacher. He hopes to turn over America to the Muslims. But if Obama were involved in such a secret agreement, then wouldn't he have just condemned Reverend Wright from the beginning?

In all these respects, Obama does offer a non-polarizing and inclusive alternative to traditional political engineering, and we must embrace the possibility that America is ready to engage with itself and the rest of the world in this way. True, it would make it more difficult for us to drop bombs on other countries because we might see them as real people. But it might also make it less necessary to drop bombs on them, or even to kill or starve them in other ways. This is all good.

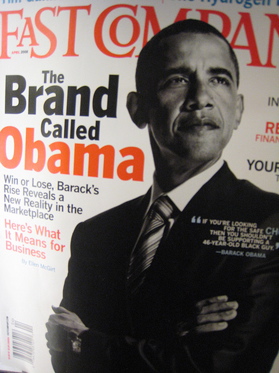

Where the Obama effort has always disturbed me, however, is in how branded it all feels. From the beginning of his candidacy, I felt as if the Obama name and image represented a new way of doing things more than it exemplified it. My own sense of cynicism reached a peak when Oprah Winfrey began campaigning for him. I've watched her similarly enthused by fakers from Tom Cruise to the founders of The Secret. Oprah's "energy," if you will, is that of national branding. Oprah + (insert your product here) = MegaBrand. Using Oprah to push Obama feels a bit like using rock to push religion. But it's not fair to criticize Obama for letting a powerful media celebrity attempt to teach her followers why he'd be good for the country, is it? He needs to get elected, after all.

Then there's Obama's efforts to reach out to new audiences online. And for sure, Obama's Facebook/YouTube/website representation is far beyond anything Howard Dean and his folks did last time out. Where Dean's people inserted their stock candidate into an online fund-raising campaign, Obama's message and media are more organically related to one another. His message is about invigorating bottom-up, grass-roots, community organizing – and the Internet is that, if anything.

Still, a closer look at Obama's online effort reveals many opportunities for work, and few opportunities for what I consider to be intelligent participation. We can sign up to make phone calls, send emails, volunteer in the streets, or become precinct captains. But where's the participatory democracy wiki? Where do we get involved in the conversations that help shape his policy positions? How is he incorporating the massive intelligence of his support network into his philosophy of governance? BarackObama.com is a great example of crowd-sourcing, but it's a far cry from even a fledgling effort at open source democracy.

Then again, by the very design and scale of national politics, no presidential campaign could offer more than a wink and a nod to true participatory politics. Activism isn't something that happens on TV for a general viewing audience, but at home with real people who aren't watching the tube at all. While a president can provide some inspiration – Oprah-style, if need be – for a whole lot of people, the executive isn't the locus from which real change occurs. As president, Obama could enact policies that make activism easier to accomplish, jobs easier to create, and corporations more easy to resist – but this activity itself would have to come from us.

Brands were invented primarily to replace local commerce and social activity with mass produced goods and corporate-provided services. Brand mythologies alienate people from one another and insert themselves in the place of real relationships. Instead of buying meat, corn, drugs, or soap from local producers, we buy them from A&P, Green Giant, Wal-Mart or P&G. These national brands have great mythologies, but serve to disconnect us from one another, and distribute power to those with capital and away from people who actually do work.

The danger in Brand Obama is that our focus on a heroic or mythic presidency could easily distract us from the hard work and reality of creating change ourselves. "Hard working" democrats loved listening to Hilary Clinton talk about how hard she was going to work for them because it made it seem like the president is in position to stay up all night and, through the extra effort, get food on our tables or money in our bank accounts. It just doesn't work that way, and Obama's refusal to, say, cut gas taxes over the summer to cater to this mentality speaks volumes.

The best thing about Obama is what appears to so many people to be his hesitancy. For many, it tarnishes his brand. As I see it, this is not lack of resolve at all but his greatest strength. He stutters and stumbles – but usually because he's trying to answer a question in a way that doesn't make himself out to be the answer to an abstract and collective problem. He understands that the presidency is itself a social construction, and that agreeing to "play" president is a mutual agreement – not a genuine ascendance. TV's West Wing may have done more damage to the Left than we know. It gave us undeserved solace during the darkest Right wing presidency in history, and created false hope of how much the White House could accomplish with the right leader in the Oval Office.

Those of us hoping to build communities, improve our schools, invigorate our local economies, restructure our land use, or reduce our energy dependence mustn't equate a presidential campaign with substantive change. Obama may be a convenient conceptual placeholder for these concerns, as well as a person capable of dismantling a good amount of America's more fascistic and militaristic infrastructure. But the only way he'll even have the latitude to behave in a slightly more enlightened manner than his predecessors will be if we, the actual people on the ground, have chosen to live more consistently with those goals. If he's president of a nation of fast-food-eating, bigoted, and selfish SUV drivers, he'll prove as powerless as Cheney was malicious. And the results will be the same.

Obama can help legislate some of the structural changes that will make it easier for us to renegotiate our civic, social, and commercial relationships with one another. But the job of actually changing society and its priorities will happen from the bottom up. He can help write laws that make it easier for us to build transportation alternatives, but we have to actually go do it. That's how representative democracy works; they represent our interests, but we do the actual stuff.

Yes, I'll be voting for Obama and, assuming enough votes are counted, will be happy to see him as our next president. But I'll also remember that this will only mark the beginning, not the conclusion, of my participation in the democratic process.

This article originally appeared on Rushkoff.com.

Image by MotherPie, used courtesy of a Creative Commons license.