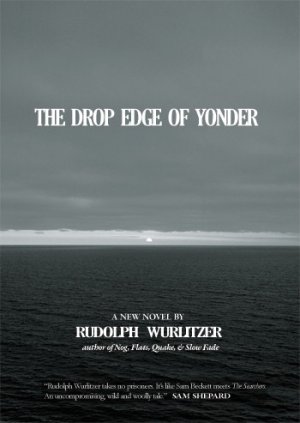

This story is excerpted from the new novel, The Drop Edge of Yonder, and is reprinted with permission of the publisher, Two Dollar Radio.

HATCHET

JACK AND ZEBULON RODE NORTH ACROSS THE high desert towards the Spanish Peaks of the Sangre de

Cristo Mountains. Two days later they reached the cabin, a hard little stand at

the end of a steep valley, quilted halfway to the roof with drifting snow.

Nothing much had changed. The cabin's roof still had

most of its shakes blown off, the makeshift corral hosted three starving mules,

and a curl of smoke drifted up from the chimney like a lonely question mark.

After they walked their horses over the ice-covered river that snaked in front

of the cabin, Zebulon hollered a long "Hallooo." When there was no answer, they

secured their horses inside the sagging corral and pushed through the stiff

door of buffalo hide.

An ancient stern-faced woman sat behind a three-plank

table in patched red long johns, pointing a shotgun straight at them. In front

of her a torn deck of cards was spread across the table for a game of

solitaire. Brown streaks of tobacco juice ran down her chin, and a thin curtain

of gray hair fell over one side of her ravaged face.

"I thought it was your Pa come back," she said to

Zebulon. "I was lookin' forward to smokin' the old grizzle-heel straight to

hell."

She looked him over top to bottom. "A bit off your

graze, ain't you, son? Last I heard you was hangin' out with flatlanders and gold-suckin' Argonauts."

"I was, Ma," Zebulon said.

"No more."

"You sure are a sorry piece

of used up sod," she went on. "You look like a damn ghost. Beat-up and thinner'n

a snake on stilts."

"I'm comin' around," he

reassured her.

"You might be comin', but

you ain't yet around."

"Howdy, Ma," Hatchet Jack

interrupted.

"Howdy yourself," she

replied, spitting a thick stream of tobacco juice in the general direction of a

copper spittoon. "And don't Ma me. Use my Christian name or put your

scrawny half-breed ass back on the trail."

"All right, Annie May."

Hatchet Jack picked up a bottle of whiskey from the table and took a long pull,

then handed the bottle to Zebulon.

"You got some big fat cojones

comin' back here," Annie May continued. "Last I heard you was down on the Brazos rollin'

steers and makin' mischief."

"No future in steers these

days," Hatchet Jack said.

"I'll vouch for that,"

Zebulon said, pulling off his bloody shirt and dropping it on the dirt floor.

"I'll just bet," Annie May

said, shooting him a weary glance. "Vouchin' bein' a particular specialty of

yours. That and poochin' stray women."

She turned her head towards

Hatchet Jack. "What brings you here?"

"I need to get square with

Pa," Hatchet Jack said. "I mean, Elijah. Finish my account with him."

"You gone to Jesus, or just

loco?" the old woman asked.

"He's become a healer,"

Zebulon explained.

Annie May cackled, slapping

her arthritic knees with her palms. "Well don't the sun just shine. You're too

late, Mister Healer-Dealer. He took his sorry ass to Californie. Who knows where?

Now you got me to deal with.

"It ain't the same."

"The hell it ain't. The

horse and traps you stole were mine the same as his. By rights I should plug

you for thievery and be done with you."

Hatchet Jack shrugged.

"That's up to you. I still got a horse to give back, even if I lost the traps."

"We'll eat," she said

firmly. "Then speculate."

She sighed, shifting her

gaze to Zebulon, who was slicing up a pair of his Pa's pants with his bowie

knife.

"To think you're all I

spawned," she said. "All that I care to recollect anyways."

She picked up the bottle of

whiskey, studying his bloody chest. "What happened to your pump?"

"I guess I been shot."

"You guess?" She hobbled

over to him and poured the rest of the whiskey on his chest, an act that made

him howl more from witnessing the last of the bottle than from the acute pain.

He shuddered as she carefully wrapped a strip of pant leg around his chest.

"How come there ain't no

bullet hole?" she asked.

"I wondered about that," he

said.

"Might be the slug passed

through you. Who done it?"

"Most likely a pecker-head

sneakin' a card off the bottom." He nodded at Hatchet Jack. "That's what he

says, anyway."

"You was there?" she asked

Hatchet Jack.

"I come in after the show

was over," Hatchet Jack said.

Satisfied with her nursing

skills, Annie May stood up. "Don't neither of you burden me with your sad

stories," she cautioned. "Or what you done or ain't done or what you're goin'

to do. I'm too old for that bullshit."

She took down a tin of

biscuits and a slab of jerky from a sagging shelf. After she dropped the food

on the table, she sat down, lit up a curved ivory pipe, and watched Hatchet Jack

and Zebulon eat.

"Raise many pelts this

winter?" Hatchet Jack asked, chewing hard on the jerky.

Annie May shrugged, then

let loose another streak of tobacco juice, missing the spittoon by a foot. "I

floated my share of sticks, but the haul was damn thin. Not much beaver, a few

muskrats and otter, the odd fox. Hardly worth the trouble. Far as I'm

concerned, the mountains be finished. Leastways for this old sow."

They passed around a second

bottle of whiskey. When the bottle was empty, Hatchet Jack and Zebulon lay down

on a pile of pelts, too tired to pay attention to the rats sniffing across the

floor for crumbs.

Annie May closed her eyes

and continued to smoke, enjoying the smell and presence of two snoring men.

When the memories of a newborn son and a mountain lover who wouldn't quit

threatened to overwhelm her, she stumbled off to her own bunk in an add-to

behind the stove.

~ ~ ~

The next morning Zebulon

cleaned out a weasel nest underneath a rafter while Annie May sat by the

window, watching Hatchet Jack sort out her meager display of pelts, then cinch

and slap them over the backs of two emaciated mules.

"Never thought I'd see both

of you at the same trough again," she said. "Not after what Hatchet pulled with

your Pa. Not to mention your Pa with him."

"He's askin' forgiveness,

Ma. That ain't easy."

"Forgiveness ain't in my

possibles bag. If your Pa was here, he'd give him a taste of forgiveness upside

the head."

Zebulon opened the door and

threw out the weasel nest, looking at Hatchet Jack who was kneeling on the

ground, carefully shoeing one of the mules.

"Hatchet's pulled me out of

a few scraps and shoot-outs," he said. "I owe him for that."

Annie May shrugged. "You

always were a sucker for idiot kindness. Truth is, your heart slammed shut when

Pa brought Hatchet back and he tried to drown you in the river. I had to pull

you out by your hair. Ever since then, you'll take any bone thrown to you."

She sighed, not remembering

how much Zebulon had been told about Hatchet Jack.

"I'll tell you some things

Hatchet picked up from your Pa," she said. "Dealin' off the bottom of the deck.

Settin' someone up and draggin' him to hell and then tellin' him he done the

opposite. For spite and pleasure."

"He's slick all right,"

Zebulon acknowledged. "I'll give him that."

"Never mind," she went on,

as if she was having second thoughts. "He's still kin. I raised him almost the

same as you, a fact that calls for some measurement, if not in the eyes of the

Lord, then from you and me. Poor lost-and-found half-breed bastard."

She took a deep breath

before she finally said what was really on her mind: "Tell you one last thing,

son. After I sell my pelts, that's it for me. I ain't about to wait for my last

days stretched out in a low-rent room over some dumb flatlander's store."

"Maybe I should pack you

down to old Mex," Zebulon suggested. "Let the sun warm your bones. Fix you up

in some little hacienda with a front porch and a cantina down the

street. There are worse ways."

"What the hell would I do

in old Mex? Chew my sorry cud with all them bean and chili-eaters? Nossir. When

I take my carcass to the misty beyond, the sky will be my blanket and I'll have

a mountain to lean against and a jug to pull on. That'll be enough."

He had grown up hearing

this statement, or at least variations of it, and depending on her mood he

always gave the same reply:

"You brought me into the

world, Ma. I'll see you out."

This time she interrupted

him: "I didn't raise you for false sentiments, son. You do what's in front of

you and I'll do the same."

THE

FOLLOWING MORNING THEY ALL RODE OFF INTO A SOFT spring rain. They took their time, as Annie May was in

no hurry to be shut of the only place she had known for thirty years, a place

she was beginning to realize she would never see again.

That night they camped among the crumbling ruins of an

abandoned pueblo, the wind howling around their fire like a chorus of

grieving widows. Halfway through a meal of Annie May's remaining biscuits and

dried jerky, Hatchet Jack stood up, his head swiveling back and forth.

An ancient Mexican stood in the shadows, his nearly

toothless face marked by an empty eye socket. His skeletal frame was wrapped in

torn leggings and a long white cotton shirt.

"You leave a trail like a wounded buffalo," the

Mexican said with a soft Spanish accent.

"Plaxico!" Hatchet Jack exclaimed. "How did you find

me?"

"I didn't find you. You found me."

"But -"

"Your problem is that you think too much. And not

enough."

Without another word, he turned and disappeared.

Spooked by the old Mexican's ghostly appearance, Annie

May paced back and forth, raising her arms against the elements: "Hurrah fer

mountain doin's and all the old warriors in all the times! My boys and I, we come in

peace and we'll leave in peace and we'd be grateful if all you dead and dyin'

red niggers and bean-eaters put the stopper on your salutes. One day soon I'll

pitch my tent inside the big circle. But not now. Not this night."

Zebulon and Hatchet Jack

joined her, shuffling their feet around the fire, faster and faster as they

hollered their mountain yells: "Waaaaaaaaagh…! Waaaaaaaaagh…! Waaaaaaaaagh!"

Collapsing on their backs,

they finished the last of the whiskey as they sang an old family song:

Old Long Hatcher gone under on the north

Platte,

Found him a bar but the bar laid him flat.

Hatchet Jack reached into

his pocket and removed a paper bag full of penny candies. Popping half of them

into his mouth, he threw the bag to Zebulon, who took a fistful and passed the

bag to Annie May, who gobbled up the rest.

"We're markin' the bush on

sacred ground," Hatchet Jack said. "Plaxico might make us pay for that."

Annie May sighed. "You seen

one old buzzard around these hide-outs, you seen 'em all. The hell with him.

I'll settle for a healing. What about it, Mister Healer-Dealer? Can you strut

your healin' stuff? Got me a bad knee, shoulder ain't right, arrowhead been

stuck in my leg for ten years, teeth gone or rotten, sluice line to my gut

plugged up. Not only that, but I'm spiteful with bad notions."

"I can handle that," Hatchet

Jack said, showing no confidence at all.

"Check out Zeb while you're

at it," Annie May suggested. "He's tough to figure, shot up with no bullet in

his pump. Like he don't know if he's here or down under."

Hatchet Jack shook his

head, not wanting to go ahead with any of it. "I never done two straight up. I

always been the helper."

"Yoke us up anyway,"

Zebulon said. "Never mind the windy complaints."

Hatchet Jack poked their

shoulders and cheeks with his forefinger, blowing tobacco smoke over their heads

and shoulders and into their faces. Then he stood up and opened his arms to

include the night sky and the black clouds drifting beneath a quarter-moon like

a procession of giant bones.

"Old Father," he cried out,

"don't contrary me now!"

Arching his neck and head,

he shut his eyes and sank to his knees, pounding his fists on the earth.

The wind stopped as if

turned off by a spigot.

Annie May shook her head in

wonder. "I'll be stripped naked and fried in goose grease. Maybe the boy ain't

such a lyin' shuck after all."

As the wind rose again,

Hatchet Jack disappeared into the darkness. Just when they thought he had run

out on them, he returned.

"Plaxico says it's all

right to join him."

They followed Hatchet Jack

down a steep path, descending a series of narrow, winding steps that led to a

stone platform lit by a fire and a single torch set into a cliff. Beyond the

platform, a deep canyon separated two mountains shaped like pendulous breasts.

Plaxico sat cross-legged on

one side of a large circle made from white flour mixed with corn shuckings and

colored stone beads. Above him on the crumbling walls, mounted warriors threw

lances at running mountain lions and antelopes.

Hatchet Jack motioned for

Zebulon and Annie May to sit opposite Plaxico, then took a position at the

lower end of the circle, behind an altar of flat stones. On one side of the

altar, a statue of the Virgin Mary had been placed next to an eagle feather and

a brightly colored Kachina doll. On the darker side, the skeleton of a rattlesnake

circled a human skull. A dozen tomahawks, as well as swords and hunting knives,

were stuck in the ground in front of the altar.

Hatchet

Jack stood up. "This medicine is from old Mex. It raises the dead and then some. It

has the power to cozy up to the underworld of the snake, the middle world of

the mountain lion, and the higher world of the eagle. I never tried it, but

that's what I been told. So here goes."

Plaxico sat behind the

altar pounding a flat drum and chanting an incomprehensible prayer. He broke

off a few times to yell instructions in Spanish to Hatchet Jack, who motioned

for Annie May and Zebulon to stand at the top of the circle. Then he approached

them holding a hollowed-out gourd in both hands.

Hatchet Jack drank, then

offered the gourd to Zebulon, who drank and passed it to Annie May. After she

drank, she handed the gourd to Hatchet Jack, who handed it to Plaxico, who

finished what was left. After a consultation with Plaxico, Hatchet Jack pulled

a long curved sword out of the earth and rushed straight at mother and son,

yelling and dancing around them as he slashed the sword above their heads.

Annie May and Zebulon stood

as if their feet had been nailed to the ground as Hatchet Jack replaced the

sword in front of the altar and collapsed by the fire. Behind him, Plaxico

swayed from side to side, shuffling around the circle, moaning and shaking his

rattle.

The medicine roared through

their bodies in noxious waves until they sank down on all fours, vomiting and

heaving until nothing was left inside them. They stayed that way until the

first light of dawn shuddered over the horizon. As the mountains grew bolder

and more defined, Annie May cried out at a long parade of skywalkers moving

towards them over the snowy peaks. Some were conquistadors and mountain

men, others Hopis, Navajos, Zunis, and Apaches. All of them were raising their

arms to greet the rising sun. Behind them, bringing up the rear was Annie May's

long-dead brother. He was followed by her mother and father and then the

preacher of her youth, who used to terrify her with fiery sermons on sin and

repentance, and who now seemed, as he looked over the valley, sad and confused.

The sky shifted and the parade dissolved as she saw an image of herself as a

young girl standing in the middle of a field of tall, wavy grass, a bonnet

pulled over her head, her bare feet planted on the black earth, crying out in

fear as an eagle glided towards her in slowly decreasing circles. Her mother

watched from the door of their homestead as the eagle gently lifted her up in

its talons and flew her across the grassy plains into the foothills and

mountains beyond. Fragments of her life appeared one after the other: her first

shoes; her marriage bed; the long white beard of her father as he stood behind

the mule on the last furrow of a plowed field; her husband, Elijah, whirling

her around a dance floor, then carrying her on his shoulders through the door

of the cabin he had built for her; and there was baby Zebulon crawling over the

dirt floor. She wept and wept, haunted by the memories and the approaching

shadow of her own death.

"Are we dead?" she cried.

"Or does it just seem that way?"

Zebulon cradled her frail,

broken body in his arms as Hatchet Jack, seized with his own visions and

oblivious to her racking sobs and sudden peals of laughter, smacked the earth

with his palms. "Who are my real Ma and Pa," he howled, "and why have they

forsaken me?"

The only answer was the

howling wind.

"Can you see the truth of

it, boys?" Annie May shouted. "Life and death. The eagle and the washing up and

the outhouse. The stove and the snow. The horse and the mountains and the 'baca

juice. No doubt about it. The whole stew is only a passing, you and me and all

the rest. The goddamn joke is on us, boys!"

Zebulon

made his way to the edge of the platform. In front of him the mountains were

undulating like three copulating snakes. He wept at the energies threatening to

consume him, motherly and loving, violent and terrifying, a warm hissing breeze

that flowed through the strangled knots of his being. He knew what he had

always known and had always forgotten: that he was composed of the same elements as the plants and

animals and the rain, which was now spreading in thick sheets across the deep

valley, followed by the sun and then a rumble of earthshaking thunder that

suddenly transformed into the roar of a mountain lion. He was part of it all, a

drop of water in the ocean, a crushed wild flower under the heel of an outlaw's

boot, a sun-baked skeleton in the desert.

When Hatchet Jack loomed up

in front of him, the vision dissolved into a vaporous fog.

For the rest of the night,

mother and son slept in each other's arms, each comforted by the other's

breathing. When they woke they were alone and the sun was shining directly

above them as if through a huge prism.

Behind them, the altar was

gone and the circle erased, as if none of it had ever existed.

Empty of thought or any

emotion, they climbed up through the ruins until they found Hatchet Jack

packing his horse. Plaxico sat against a crumbling wall, rolling a cigarette.

"I'm pullin' out." Hatchet

Jack's hands shook as he swung into the saddle. "Some of the medicine worked

and some went south." He looked at Plaxico, then at Annie May. "The spirits

told me it wouldn't be a good idea to give you the horse."

"Who cares about any of

it?" Annie May said softly. "It's all the same, horse or no horse."

They watched Hatchet Jack

gallop off without a wave or a look back, as if pursued by a confusion of

unknown mysteries.

"He talked to some of the

spirits all right," Plaxico said. "But he choked on the rest. Too big a meal

for a beginner."

And then he, too, was gone,

disappearing back inside the pueblo.

ANNIE MAY

AND ZEBULON SMELLED BROKEN ELBOW BEFORE they saw it. What had been a trading post and a few

shacks only a year ago was now a long, rutted street dominated by pandemonium

and open sewage. Drunken miners shouted back and forth in a dozen languages, a

naked Chinaman crawled past them into an alleyway pursued by a screaming whore,

half-dead oxen pulled overloaded supply wagons through mud and melting snow,

past signs advertising wares at outrageous prices: Boots $30, Flour $35,

Blankets $30, Washing $20. Every square foot of ground that was not lived on

was cluttered with mining equipment, dead dogs, pigs rooting in piles of

stinking garbage, wagon beds, spare wheels, barrels, and stacks of lumber, as

well as makeshift corrals where mules and horses stood knee-deep in muck.

Further away, on the banks of a swiftly moving river, hundreds of high-booted

men — most of them Indians, Mexicans, and Chinese — squatted beside cradle-like

gold washers and sluice boxes while others worked up a canyon in steep pits,

hacking at the soil with picks and shovels.

At the end of the street, they reined up in front of a

two-story trading post.

Inside the cavernous room, clerks ran back and forth

filling orders in Spanish, French, and English for rifles, canned goods,

farming equipment, wagon beds, and sacks of feed. A few of the older clerks

waved to Annie May as she approached a plump young man perched at a high-top

desk, adding up small sums inside a huge ledger.

Annie May pulled herself up

to her full height, which was barely up to the level of the desk.

"I'm Annie May Shook, and

I'm here to sell my pelts."

The clerk nodded, not

looking up as he took off his glasses and rubbed his strained red-rimmed eyes.

Annie May rapped on the

desk with the barrel of her shotgun. "I want both ears when I'm talkin',

Mister. Where be the major?"

The clerk took his time placing

his glasses over his nose. "Major Poultry sold out last winter. You'll deal

with me now."

"Always was partial to the

major," Annie May said. "Dealt with mountain folk straight up."

"Business is business," the

clerk said with measured patience. "Whoever be the buyer or seller."

Annie May scratched her

head, took out her pipe, began to light it, then shoved it back inside her

buffalo robe. "All right, then. What be the price of pelts?"

The clerk looked down at

Annie May as if her presence was an annoying fly. "The bottom has fallen out of

the fur market. It will never come back. That said, I'll give you fifty cents a

pelt. Take it or leave it."

She stared up at him,

unable to comprehend. "The hell you say."

"The numbers come down from

St. Louis, Ma'am. Trade or cash."

Her voice rose to a shout.

"Two dollars a pelt, Mister St. Louis. And my usual loan on 'baca, cartridges,

and flour. That's the way it's been for these thirty years, and that's the way

it'll be. Nothing more, nothing less."

The clerk shut the ledger

with a loud snap. "I'm afraid that's impossible."

"Well then, Mister St. Louis,

let an old mountain sage hen show you her possible bag."

Annie May waved her shotgun

at the clerk, then at a window, then at a row of pickle jars.

The terrified clerk backed

away, bumping into Zebulon who shoved him against a shelf of canned goods,

sending him and the cans crashing to the floor.

This was more like it,

Zebulon thought, looking around the room. This was what the old Spirit Doc

ordered when he needed to stir things up. He reached behind the counter for a

jug of liquor, uncorked it and took a long pull, then tossed it to Annie May,

who caught it in one hand. As the clerk staggered up from the floor, she

smashed the jug over his head.

"Hurrah fer mountain

doin's!" she shouted.

Hauling herself onto a

table, she fired her shotgun into the air. The pellets struck an overhead gas

lamp that exploded when it hit the floor, sending a rush of flames roaring

towards the ceiling.

"Hurrah fer mountain

doin's!" Zebulon shouted.

He yanked off a large gold

nugget that hung from a string around the clerk's neck.

"For settlement," he said.

Then he picked up an ax

handle and knocked over a shelf of air-tights and smashed a window as customers

grabbed whatever goods were close to hand and started for the door.

Zebulon found Annie May

slumped underneath the table, a bullet through her chest. As he gently gathered

her into his arms, a barrel of kerosene exploded behind them, collapsing the

ceiling, blowing out windows, killing two miners, and setting the building on

fire.

Zebulon carried Annie May

outside and laid her on the sagging wooden sidewalk. Around them, a line of men

were hand-rushing buckets of water to pour on the flames.

Annie

May's voice faded to a whisper. "Deer is deer… elk is elk and this mountain

oyster is a gone coon…. I done you wrong a time or two, son, as you did me… but that's family." She

raised herself up, trying to see him as her eyes clouded over. "Always figured

I'd go out the old way. Straight up and on my own breath…. But we caused a

commotion in this town, did we not, son?"

"So we did, Ma," he

answered.

"Did I ever tell how

Hatchet come to be with us?"

"You never did," he

replied, even though she had told him endless times.

"Pa won him from a Mex at a

rendezvous down on the Purgatory…. Everything was in the pot, everything the

Mex had – his traps, horses, pelts, and even little Hatchet as a throw in. No

more than a stump, he was. When Pa palmed the last card, he got caught, which

bothered him enough to carve the Mex up for callin' him out. Pa took Hatchet

back with him out of guilt, and maybe because he thought he could use another

hand. He was always one for slaves, your Pa…."

Her voice stopped and he

thought she was gone, until he heard her again.

"Are you with me, son?"

"I'm here, Ma."

"All right, then. Hatchet

was a weird boy. Always tryin' to drown you in the river. And then you tried to

do the same to him, just to get even…. When you find your Pa… tell him…. Hell,

don't tell him nothin'. He never did a damn thing for us except bring misery.

And now he's trotted off to the gold fields. The old cocksucker."

She looked up, her eyes

pleading with his not to ever let her go, and then she died.

He sat holding her as the

lines of water buckets were passed back and forth. When the fire was out, the

sheriff and the owner of the trading post, along with several clerks,

surrounded him with drawn pistols. One of the clerks carried a rope with a

noose tied at the end.

As Zebulon was pulled to

his feet, Hatchet Jack galloped through the crowd, pulling a saddled horse

behind him.

Shots were fired, but

before anyone could mount up to follow, Zebulon and Hatchet Jack had

disappeared down the street.

Ten miles outside of town

they parted company, Zebulon for old Mex, Hatchet Jack for California, where he

figured to make peace with Elijah.