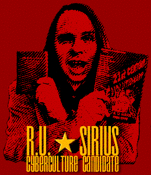

RU Sirius is a writer, musician, and counterculture icon. The magazine he co-founded and edited, Mondo 2000, was a staple of the psychedelic cyberculture in the early ’90s. His latest book, True Mutations is a collection of interviews focusing on the potentials of technology and consciousness, and the emerging relationship between the two. Sirius also takes an active interest in politics, running for president in 2000 as a candidate of the Revolution Party. He has written for Wired, Time, and Rolling Stone, and co-authored Timothy Leary’s last book, Design for Dying. In this interview, RU Sirius shares his thoughts about the future of biological and cultural mutations such as transhumanism, Virtual Reality, and life extension; the philosophies of Terence McKenna and Robert Anton Wilson; and Open Source politics.

TG: Hello, RU – thanks for talking with me. In 2004 you published a book called Counterculture Through the Ages: From Abraham to Acid House which chronicles the existence of various “countercultures” and revolutionary figures throughout history. I’ve recently been reading some of Jacques Derrida’s writings, and one of his most interesting ideas is that there is a perceived “center” and “margin” binary distinction in culture which attempts to separate mainstream from fringe ideologies. Derrida argues that although, there is thought to be a difference between the “center” and the “margin” of culture, actually they are inseparable. How do you think the counterculture and mainstream culture are related? Will there always be a subversive counterculture as long as society exists?

RU: Regarding Derrida, obviously human beings who share a place and time, and most of all a language, together are going to influence each other and have commonalities and shared underlying assumptions. So there’s not some kind of non-permeable boundary around counterculture – or the notion of counterculture – and mainstream, although in the context of the Counterculture book, I would refer you to certain discussions in there. For instance, the Qalanders in the Sufi tradition – they were forest-dwelling, hairy, sexually-free, hallucinogen imbibing wild men and women in thirteenth-century Middle Eastern Muslim culture. Since I wasn’t there, I have no way of knowing, but it’s lovely to imagine them as way “dropped out” – radically different from the mainstream culture or cultures around them at that time. Genuinely apart. I’d say the same thing about some of the Taoist hermits and “blockheads” in ancient China, as discussed in the book.

In some ways, I like to see some of these as examples of drop-outs from the Darwinian evolutionary struggle. It seems that there are reward systems that are built into our brain chemistry – they reward success (it feels like cocaine) and social approval, or at least acceptance. I like to think that certain dropped-out groups in human history have discovered a different reward system that is also somehow built into the human system – one that might be related to a mind-opened engagement with experience itself. Or it might simply be related to the absence of stress from refusing to participate in whatever rat race was particular to that culture.

Anyway, in terms of language, sure – for the purposes of the book, the word “counterculture” was used out of convenience. We could quibble about or deconstruct the language, but hopefully people will read the book and sense that there have been cultural movements throughout human history that had similarities with the twentieth-century movements commonly identified with the word counterculture. And they’d perceive that this book would describe and display some of these cultural movements or tendencies and show how these kinds of dynamics between a “mainstream” and a “counterculture” seem to reoccur with great frequency.

Now as to your question of how counterculture and mainstream culture are related. Since you ask the question in the present tense, I think the question is mostly moot. I don’t think there is a mainstream culture anymore, or perhaps I should say the mainstream isn’t really a culture anymore. When we say something is mainstream, I think we’re often just talking about a bunch of miscellaneous purchase selections that happen to be made by large numbers of people: what are the most popular brands and what types of entertainment are people choosing? And that’s pretty much our shared “culture.”

And deconstructionism to the contrary, I think you can drive yourself nuts trying to attach too much significance (or trying to find too much resonance) from what people purchase as consumers. At its core, I think that our version of consumerism is just the pretty vacant response of lots of people passing the time without a clue, in a society where nothing much coheres.

Another way of looking at it is that the “mainstream” is now a faux counterculture. It’s got your Starbucks café society: all the various hip brands as reflected by their advertising, all the cool gadgets with their well-advertised youthful hipster appeal for connecting and having fun. It all kind of strives for “counterculture lite.” People are encouraged to “think outside the box,” which is a sort of utterly neutered version of the idea of transgressing taboos that was vital to authentic “countercultures” and a notion that is very much central to our book (I must acknowledge my great co-author Dan Joy).

Before leaving this question behind, I want to say that I’m personally very unenlightened and not a dropped-out Taoist blockhead master by a long shot. In fact, I despise being perceived by people with money, power, and influence as “marginal.” I think it harms me – it assumes that I can’t have as much agency in this world as they have. I think there’s some kind of dynamic at work there where those with a certain lingering market-consensus mentality assert their dominance by taming people and ideas that might otherwise be challenging. They do this by “loving” outsiders qua outsiders, and defining them within the marketspace as having there own little place of acceptance – a place on the far end of the “long tail.”

There’s also a kind of cultural tourism at work there. For instance, radical pranks from the margins of politics and culture become entertainment by the time they’re reported in The Wall Street Journal or Time or Wired. And then you had the whole Gen X mentality where hipster cultural tourists gained some sort of satisfaction out of digging on obscure artists or genres and so forth, and then felt that their pleasure was ruined if those things became less obscure – their small cultural tourist scene got commercialized. I never cared for that mentality, but then again, I’m a boomer. And, you know, people tried to put us down just because we got around. Dude, it like totally harshed my mellow!

Yeah, the faux-radicalization of mainstream culture is always kind of pathetically amusing. Corporate marketing reaches out to the radical and socially disenfranchised elements of society because they are untapped market space. How ironic. Good thing there are still people like you out there to carry the perennial torch of true weirdness! *Laughs*

On a more serious note, one of your many interests as a writer and social thinker is politics. In 2000 you ran for President of the United States as a candidate for the Revolution party. More recently, you published a manifesto of sorts for your new “Open Source” and “Question Authority” political organizations. In these writings you offer some reasonable criticisms of our current governmental structure and a plan for a new political party, the Open Source Party. After discovering a plethora of information indicating that both the 2000 and 2004 elections were severely compromised by various forms of fraud and disenfranchisement, I came to the conclusion that our current democracy is in dire need of restructuring if it is meant to serve the interests of the people. When I talk to people about these issues it seems that not just myself, but many people are losing faith in our current political system – the corporate “duopoly” as you have referred to it.

After putting some thought into the problem and researching about our current form of government, I realized that our current system of representative democracy in America is rather antiquated, and with the rapidly increasing development of information technologies, computer networking, and the ease of transmitting and organizing information through the Internet, a new form of government is now possible which would enable each citizen to have their own vote on each issue, a system in which there would no longer be a need for politicians or lobbyists or political parties: a true democracy.

‘There are literary precedents for such a governmental system in science fiction; several popular SF authors have already envisioned similar political scenarios. For example, in Dan Simmons’ Hyperion saga, characters across multiple planets within the inter-planetary government are connected through a cybernetic neural network, enabling them to instantly access information on political issues and cast their vote on any issue that’s on the table at any time. In The Golden Age trilogy by John C. Wright, powerful “post-human,” technologically augmented characters interact with the political system on individual terms, making their own decisions within a telepathic collective government, without need of political representatives.

So after considering these ideas, I am very interested in your new political party, which seems to be proposing a system similar to what I’ve described. What is the intention behind the idea of “open source” politics?

First of all, Open Source Party is a proposed political party and Question Authority is a proposed political organization.

I think the most important and immediately useful connection between the idea of open source and its application to politics is not so much the direct democracy ideas that you suggest as it is the idea of transparency at a real deep level – everybody has access to the source code and can use it any way they want.

In addition to transparency, Jon Lebkowsky, who is very much a partner in this project, has described collaboration, emergent leadership, and adaptability as qualities of open source that can be applied to politics. How this can be applied to our current politics is really complex and would require an essay of its own. In fact, it requires more than an essay. It requires the collaborative process we’re trying to engage by creating the Open Source Party.

Ultimately, yes, I agree that new forms of government are possible. Back in 1973, Timothy Leary wrote an essay titled “The End of Representative Government” that pointed out that sending people to Washington to represent you was an artifact of the horse-and-buggy era when communication with Washington D.C. was days away. Leary argued that with contemporary communications technology (this was in 1973!), people should be able to represent themselves. In Leary’s ideal, people would fire off signals that represented their desires and the government would try to please everybody! This is, of course, typical Leary-esque hyperbole and futique, post-scarcity thinking. It’s there to inspire, not to be institutionalized.

I definitely think that policy should ultimately be largely democratized, but there are also a number of problems with that. You need a deeply ingrained libertarian streak within the body politic, and probably a beefed up bill of individual rights. The rights of the minority need to be protected from majoritarian interventions, so you’d be talking about democratized policymaking within a context of limited government. You also need checks and balances against majoritarian hysterias, so we don’t “nuke Iran” or start burning everybody who seems a little creepy at the stake, as “pedophiles.” I’m pretty serious about this. The tendencies for large masses of people to be drawn into irrational and even hallucinatory hysterias is well-documented.

And then there is the simple question of time and attention. How many people really can (or want to) have time to track the nuances of policy so that they can deal with it intelligently? Of course, our representatives don’t bother to do this anymore either. Here is where the open source principle of having as many eyes on a problem as possible can come into play. One Senator couldn’t possibly have read the Patriot Act in the day or two they had to read it before they were pressured to vote on it. But a dedicated collaborative group could have nitpicked the shit out of it. So, somehow instituting effective, distributed collaborations may help solve problems better than massive instant democratic plebecites.

Wow, I never quite realized that Timothy Leary’s political ideals were so visionary. I recall reading somewhere that Leary ran for Governor of California against Ronald Regan in 1969. Apparently one of his political initiatives was to disband the prison system and instead establish a “frivolity tax” for criminals to pay, rather than going to jail. This may seem absurd or impossible to some, but many people these days seem to be disillusioned with the idea that the prison system actually functions to “rehabilitate” criminals the way that politicians claim it does. Where did the satire end and the reality begin in terms of Leary’s political ideas? Do you think his ideas merely reflect the fashionable idealism of the time, or was there some real substance behind his radical re-imagining of the political process?

I don’t think Tim took his candidacy all that seriously, but who’s to say that he didn’t feel like he could win during some particularly exalted and chemically-enhanced moments. Remember, he announced the candidacy spontaneously after winning the Supreme Court case that eliminated the absurd marijuana tax, so it was possibly a moment of “irrational exuberance.” Also, of course, once he left Harvard, Leary was the breadwinner not just for wives and kids, but frequently for communes and hangers-on and friends and so forth. And his way of bringing home the proverbial bacon was to keep the “Timothy Leary Show” on the road. He always made his primary livelihood as a popular public speaker and he had to keep his name and his personas in circulation in order to do that.

By the way, there’s no shame in that. Just about everybody you’ve heard of in public life does that consciously to some degree at some point. Leary just did it well, while at the same time, he wasn’t very good at concealing his showman aspect, which stuck in some people’s craw. I don’t know – some people prefer inauthentic authenticity to authentic inauthenticity in their public figures. As for me, I’m a Warhol fan.

As far as his political ideas are concerned, he wrote and commented eloquently about political matters from time to time (sometimes under a fake name. He appeared as a frequent critic of the Reagan Administration’s policies towards Central America in letters to the editor in the L.A. Times, for instance. (They would generally reject letters signed Timothy Leary.) I think Leary’s best ideas, politically and otherwise, were expressed after the ’60s, when fewer people were paying attention.

Your political platform advocates ending the so-called War on Drugs. Bill Hicks famously commented that the drug war is actually a war on various forms of human consciousness. That view seems accurate to me: the war being waged by governments against drug use is not in reality being waged against the drugs themselves, but against the governments’ own citizens. How do we deal with a government that is ignorant enough (willfully or not) to categorize marijuana in the same penal class as heroin? If this drug war is in fact a war against certain states of consciousness, then how can anyone ever hope to “win”?

There are a lot of cracks in the drug war façade. For example, spokespeople for the War on Drugs now like to deny that people actually go to prison for mere drug possession. It’s a lie, but it’s a lie that speaks of a tremendous change in our social attitude towards drug use. And certainly, casual drug use is sort of winked at as an optional part of adult (and teenage) life in America today.

There was a period during the Reagan Administration’s big drug war escalation when the media was intimidated and drug humor was virtually eliminated from TV. Now John Stewart and Colbert and Bill Maher get cheers from the audience whenever they mention pot; you’ve got shows like “Weeds”, the kids on “That 70s Show” smoke pot, and even Tony Soprano had a sort-of-meaningful peyote experience. Most of the major Democratic candidates say they’ll leave medical marijuana alone. And, of course, starting in the ’90s, the FDA began allowing some psychedelic research and there have been all kinds of positive news reports. I was particularly amused by the New York Times headline a few months back that was based on some John Hopkins studies with psilocybin. It read, “Mushroom Drugs Produce Mystical Experiences.” Wow! Scientists Discover Ass Not Elbow!

So yes, I think there’s some hope. On the other hand, there’s a huge drug war industry and the prison-industrial complex is one of America’s biggest businesses, so those are powerful forces for maintaining the drug war. And hysteria about teens taking drugs is something politicians can still demagogue about. I think those are the reasons why the drug war continues. I don’t think the powers that be are that concerned about altered consciousness itself anymore. That cat is already out of the bag and it’s a market that they cater, too. Realistically, it doesn’t threaten the power all that much.

One of the topics covered in your book True Mutations, and also in Mondo 2000, is transhumanism. This is a field of futuristic study and speculation that can be defined in many ways. How do you describe its basic tenets?

I don’t know that I would claim to describe its basic tenets, but I’ll say what the intrigue is for me. I see it in terms of hacking. One of the basic ideas behind hacking is that you take a technological system or object and you get it to do things beyond what it was apparently intended to do or was capable of doing. So I like to think of the transhumanist movement as an ongoing project to hack the human body and the brain, and the social and material worlds outside our bodies and brains, and get them to do things that they can’t do now – including things that humans up to this point would have perceived as being in defiance of “nature.”

That has, of course, been the story of technology and technique and science and human ingenuity since day one, but now we’re looking at hacking our biologies for extended lifespans, hacking our brains for increased intelligence, hacking molecules for material abundance, building intelligences that are greater than ours – or different from ours – and so forth. We also might be looking at engineering our level of happiness or bliss, engineering out painful forms of insanity, hacking our skin pigmentation color or our physical design. As Debbie Harry put it in our Mondo 2000 interview back in 1990, “A tail might be nice.”

By the way, this is all terribly ambiguous and potentially “Brave New World.” In some ways, I’m less interested in arguing about whether it’s socially responsible to push forward with all this and more excited by the sense that it’s an irresistible manifestation of a human impulse that has been expressed in various adventure myths involving grail quests, magick, religious imaginings, science fiction imaginings, and so on. So it pleases me to imagine that human beings could win the prize, even though I’m not quite sure what the prize is. I don’t think long life, in and of itself, is a huge value. I’m interested in how all of this might open out into something extraordinary and profoundly psychedelic.

So are you saying that the transhumanist impulse to transform the body through technology is similar to the magical or alchemical goal of transforming the inner substance of a person’s consciousness? Is the modern concept of “hacking” the human brain with transhumanist modifications similar to the idea of casting a magic spell on the human mind and body, a theme often found in mythology and ancient folklore?

These imaginings, whether magical or religious or science fictive and so forth, were generally about transforming the external as well as the internal worlds. And if you study occult literature and mythology and folklore, you find magical desires that have already been satisfied by technology: the desire to fly, to project our images and thoughts and voices across great distances, travel out into the cosmos – even the desire to heal illness.

And of course the computer screen is a sort-of magic window through which a skilled hacker can cast a spell and bring him or herself all kinds of virtual magical gifts. Eventually, perhaps, we will arrive at something like Terence McKenna’s vision in which what we imagine simply comes to be.

I agree, these days humans are increasingly developing the powers of psychic manifestation of the world. And technology seems to reflect that process. I’ve been interested in the idea of transhumanism for some time now, after reading Ray Kurzweil’s seminal text The Age of Spiritual Machines: When Computers Exceed Human Intelligence. I’m a member of the World Transhumanist Assocation, and an advocate of transhumanist ideas about the positive potentials for merging technology and humanity through bio-engineering and artificial intelligence.

Kurzweil’s idea of the technological “Singularity” is essentially that the growth of technology can be understood as an exponential curve of progress, meaning that at some point in the near future the exponential value of the complexity of technology will skyrocket, and we will be suddenly be dealing with computers that are much smarter and faster at calculation than the human brain. Do you think that this kind of Singularity, the birth of A.I., as described by computer scientists and futurist authors such as Vernor Vinge, Ray Kurzweil, and Terence McKenna, will someday become a reality?

Well, here’s where I have to express my more pragmatic side. As much as I’d love to see us “break on through to the other side,” I’m not a true believer in The Singularity per se. I’m not inclined towards the sort of gospel of inevitability that appears in Kurzweil’s timelines of technological development; nor am I a believer in the psychedelic/spiritual versions of inevitable transformation. In terms of Kurzweil’s theories, I don’t assume there’s some absolute correlation between exponentially increasing processing power in machines and intelligence as we understand it. It could turn out that way, but it’s just so hugely complex. In fact, this exo-stuff could surprise us and start doing amazingly smart or strange things way before expected or, more likely, it may disappoint us.

The Singularity as imagined by Kurzweil and so forth may be an infinite regress, always just over the event horizon. Or the Vingean concept of The Singularity – the idea that when we create machines that are smarter than us, everything changes beyond our ability to comprehend – could turn out to be just so much bullshit. The human ability to snatch banality out of the jaws of the extraordinary may survive and dominate well into the post-human era. In fact, isn’t it amusing that some of the earliest expressions of the transhuman era are steroidal sports stars, massive boobs and housewives having botox parties?

Well, if artificial intelligence does eventually come onto the global scene, what do you think might happen? Some authors such as McKenna engage in wild futurist speculation involving immersive virtual reality worlds and technological utopias, while others like computer scientist Bill Joy describe the potentially catastrophic dangers of newly developing technologies such as nanotech.

Do you think that if technology is allowed to continue with little or no major restrictions, we will experience major changes in the next few decades? Is it possible that we will eventually have a technological utopia like the kind described by Terence McKenna and some science fiction authors in which the nanotech machines can do most of the physical labor and humans would be free to engage in more complex artistic and/or hedonistic pursuits?

As you may already have noticed, I shy away from predictions, but I’ll start with my boring, pragmatic answer. There are dangers, but on the whole, I think these technologies that you mention (artificial intelligences, nanotech and so forth) will most likely help us solve problems – particularly energy and suffering from scarcity and illness. And maybe we’ll even be able to use it to heal the environment of earth, and ultimately move some of the earth’s human passengers elsewhere (voluntarily, of course). So I think it’s most likely that, on the whole, these things will produce material wealth and health and give us pleasant and entertaining diversions. (And then, they will kill us! Bwah-ha-ha! Err, just kidding…)

Since you mentioned Terence McKenna, I’d like to say a few words about what an incredible visionary he was. He had this vision that the interior and exterior would change places, long before people started talking about “virtual reality.” I think that’s just incredible. Now we begin to see the outlines of a world in which younger people seem quite ready to upload their entire lives and personalities onto social networks, and we’ve got sketchy worlds like Second Life that serve as examples of this McKenna-like world where “what we imagine simply comes to be.” The end point of all that could be when consciousness is uploaded into virtual reality and we become creatures of pure imagination.

I find that one kinda scary. There have been other science fiction visions that I frankly don’t completely understand technologically in which the physical world is engineered or programmed to respond to us much like an imaginal world would. That seems preferable. It also seems like something we might not see in this century. So McKenna’s insight might remain a powerful metaphor more than an absolute.

It seems equally possible that we will be thrust into some kind of totalitarian technological hell in which our every movement is watched and our perceptions are closely monitored, a la A Scanner Darkly or 1984. It’s interesting to observe how a force as powerful as technology can simultaneously invoke great dread or great hope in people based on different perspectives of its usefulness in our lives.

Yeah, I think that’s actually more of a parallel vision than an opposite vision. These technologies could solve problems and not be disastrous in a physical sense, but they seem to almost inevitably bring on the death of the Western concept of privacy. The scenario could be hellish, considering the current political dynamics: authoritarian tendencies married to paranoias about security are at war with authoritarian outsider anti-imperialists who hate technology and modernity.

But I don’t think the scenario will necessarily be particularly hellish. It could easily resolve into a very liberal control system. In some interview during the ’80s, someone asked William Burroughs about Brave New World and he said (in that great Burroughs voice), “I think it would be an improvement.” I can imagine a very liberal society – pampered by machines – in which people are free to carry on wild festivities in the hippie/pagan/Burning Man traditions, or do just about whatever pleases them, and where the margins on behavior are set really wide, but if you slip over those margins, everybody immediately knows about it and your brain is instantly corrected so that you can’t do that taboo thing again. Instant rehab!

Hmm, that’s certainly an interesting idea. The kind of optimistic futurism that surrounds speculation about developments such as biotech reminds me of Terence McKenna’s brand of neo-pagan, techno-utopian idealism. His Alien Dreamtime video/rave lecture comes to mind. As editor of Mondo 2000, I know you are very familiar with the kind of giddy prognostication that accompanied the remarkable advances in technology and computing at the beginning of the Information Age in the twentieth century. What do you think it is about technology and the human mind that encourages people to have wild dreams of future utopias?

I think there are three answers. First of all, they may be, in some part, correct. And if you follow some of the discourse about how human intelligence works, like in John Hawkins’ book On Intelligence, the two major themes that seem to emerge are pattern recognition and prediction. To oversimplify: the brain recognizes and retains certain patterns about how the world will work, and then we act based on a mechanism that uses the pattern recognition to predict the results of our action.

So when we look at a new technology, or the emergence of lots of new technologies, our brains do what they naturally do – they perceive patterns and then make predictions based on the patterns. People were predicting the emergence of a global humanity and the breakdown of boundaries and nation states and all those sorts of things immediately following the invention of the telegraph. Thomas Friedman wasn’t even yet an arrogant little spermatozoa in his daddy’s reproductive system when visionaries first imagined that global communications could or should result in a sort of global culture – and some of them expected it all to happen very quickly and suddenly. And then, of course, even more people started predicting this same thing during the cybercultural ’90s. But old patterns (and old memes linked to old patterns) have a lot of staying power. So the new societies imagined by visionaries may tend to happen more slowly and less absolutely than they expect, or hope for.

The second answer, which is related to the first, is that there may be some kind of ingrained feedback loop between the evolution of consciousness and technology. We could do worse than consider Leary’s eight circuit model of the human brain and nervous system in this context. In this model, in very simplistic terms, new brain circuits or new patterns or novel possibilities that are inherent in our brains are awakened by technological changes. So, technologies that allowed for a leisure class also gave rise to aesthetic pursuits that may not have seemed an obvious fit for the Darwinian model. And then, a sufficiently electronically-linked up society gives rise to other types of experience and social organization and awakens other circuits or patterns or possibilities inherent in the human brain. And the same thing happens as we gain control over biology, over the molecular structure of matter, and finally perhaps over the quantum world – or we penetrate other-dimensional worlds, or whatever.

I’ve got to say, if you allow for the fact that it was written in the 1970s and was based on the science (and some pseudoscience) of its time, and if you stand back far enough and squint, you might find that, in broad terms, Leary got the pattern recognition and the predictions right even if many of the details were wrong. I’d recommend his entire 1970s Future History Series to anybody who can maintain that perspective. I also think we may, as a culture, want to look at psychedelic drugs in terms of pattern recognition.

Finally, the third answer: There is presumably some evolutionary, biological value in hope and imagination – there’s survival value in being energized and inspired. And when visionaries like Arthur Clarke or McKenna or Heinlein imagine worlds and possibilities, other generations actually try to realize those visions. One of the amusing aspects of this whole techno age is the degree to which it has been inspired by fiction.

While the possibility of full scale, perceptually immersive virtual reality as imagined by authors like McKenna may not have come into existence just yet, I think it’s arguable that crude forms of VR are available and, in fact, widely used today. For example, the world of online gaming resembles a virtual reality experience in many ways. Players assume an anonymous new identity in the virtual world which allows them to act out a life completely different from their own if they so desire.

Many MMORPGs have memberships that include millions of people in dozens of countries across the world, linking cultures technologically through the Internet. World of Warcraft has over nine million members, and several other MMORPGs have more than one million active members. Articles have been written analyzing the time spent building virtual economies in MMORPGs, showing that the labor time spent creating trade goods in online games is equal to the output of some small countries. There are millions of people who now statistically spend more time living inside those online games than they do living in the real world. Is it accurate to say that these MMORPGs represent a form of primitive virtual reality? How do you define what qualifies something as a virtual reality experience?

I’m not the first to say it: you can take it back to the cave paintings. Any shared mediated abstraction might be seen as having some sort of virtuality. So how we qualify a virtual reality experience is, appropriately, entirely subjective.

Jaron Lanier’s idea, the one that popularized VR in the early ’90s, was that it had to be immersive to at least one important sense – the visual sense. You had to block off the eyes from all outside input and put your visual sense inside of a three-dimensional visual “world” that is non-physical – presumably, initially it would be conjured by digital technology. And that’s a virtual reality that has been achieved and is used for all sorts of things, but not yet for entertainment and interaction and communication in the way that it was imagined during the tremendous hype around VR in the early ’90s.

I do appreciate the fact that game worlds – interactive imaginal worlds – are eating up a lot of mental space. I think it confuses and complexifies our shared reality. If fantasy money and value sufficiently leaks into our real world, it may become one of the mechanisms through which we – as a society that is hostile towards “welfare” – can trick ourselves into allowing ordinary people to get their fair share of “money for nothing.”

Another noteworthy trend in information technology is the increasing popularity and efficacy of peer-to-peer networks. In recent years there has been quite a lot of legal havoc about p2p networks, mainly due to pressure from the RIAA to stop file sharing on the Internet. So far, it looks as though their efforts continue to be futile. People are still sharing millions of files every day, all over the world. The war against p2p file sharing resembles the War on Drugs; they are both wars that are ultimately unwinnable because the authorities are trying to legislate peoples’ personal behavior on a scale that is not feasible to enforce. To me, it seems that p2p networks are an essential part of the Internet the same way that “meatspace” networking is essential to cocktail parties. If you get a bunch of people together in any context, they are going to share things. I think it’s very interesting how your group has conceived of a new form of politics, the open source idea, as a collaborative model that somewhat resembles a political peer-to-peer network.

When thinking about the open source idea and the potential for p2p networks to function on a social and political level to coordinate and redefine society, it occurs to me that the these p2p networks (and the whole structure and complexity of information sharing on the Internet in messageboards, in instant messaging conversations, chat rooms, online games, etc.) seems to be approaching a technological version of the “noosphere” imagined by some visionary philosophers.

The noosphere, for those who may not be familiar, is the idea that there is a level of thought-energy that surrounds the planet in a manner similar to the way that the invisible atmosphere surrounds our planet. The idea of the noosphere, or some kind of “Gaian mind” or global telepathic intelligence network, has been proposed by several authors in various contexts – most notably by Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, José Argüelles, Peter Russell, Ken Wilber, and Howard Bloom. Some authors have also related the increasing inter-connectedness of technology with the development of a global noosphere. Terence McKenna, Erik Davis, and Mark Pesce come to mind in this respect.

Do you think that if your open source idea is taken seriously, it could lead to some kind of political scenario that would resemble the concept of the noosphere? With the immense popularity of social networking sites like Myspace and Facebook emerging on a global scale with millions of users, is it accurate to say that the increasing inter-connectedness of p2p networks and social networking on the Internet is beginning to function as a type of global telepathy through information exchange? McKenna put forward this idea several years ago in his lectures about A.I. He said that with the advent of the Internet, computers had quietly become telepathic without anyone realizing it. I wonder if that’s an accurate metaphor. Erik Davis explores the idea of a relationship between information technology and the proposed noosphere extensively in Techgnosis, as does Mark Pesce to some extent in his “Hyperpeople” essays. Will the future of global politics be modeled after p2p networks?

Does this global network become the noosphere when we say so, or does it somehow announce itself or identify itself as a sort of meta-entity? At what point does it become this “thing” – this Singularity? I’m inclined to think that any perceived singularity can also be perceived as a potential, infinitely-branching multiplicity, so maybe President Bush’s blunder about “the internets” will prove to be visionary.

As to whether online computers are telepathic – well of course they are, in the sense that every machine that’s online “knows” everything that every other machine that’s online knows the instant it’s known. I’m not sure that’s interesting unless or until the machines start to become also autonomously alive, conscious and intelligent. Otherwise, it’s sort of like saying I’m psychic because I can read my own mind. Yes, I have access to the things that are in my mind. (Well, most of them anyway. On a good day.)

I guess the question then becomes whether (or at what point) we credit these machines as being alive or conscious. The broader question may be to what extent we, as pattern recognizers, impose our patterns and endow our conceptual linguistic concepts with a life of their own – and to what extent something objectively other is here, or emergent. I certainly think something objectively “other” is probably emergent but not here yet, however that’s just a guess. (I’m talking here about the “other” that might emerge from networked computers, not other “others” that might be hanging around. I’m strictly agnostic in that regard.)

As far as whether Open Source politics is modeled on p2p networks, I think open source economics, in some sense, may be based around p2p. Implicit in p2p is the idea that wealth that is infinitely replicable should be shared, and that hoarding ideas and other digital stuff in a networked world is both silly and impossible. If we get into molecular engineering, where we’re dealing with physical matter as replicable information, p2p becomes the mechanism for liberating the codes for making material wealth. It also presents a challenge to construct new economic relations that will allow and encourage the people who create the “content” – the digital stuff that gets replicated and shared – to do their best and most valuable work within what is fundamentally a gift economy. Open Source politics, on the other hand, probably implies a confluence of all the tools that seem implicit in open source culture, including wikis, p2p, social networks, game cultures, and all other collaborative, fundamentally non-hierarchical tools.

True Mutations documents advances in biotechnology which may eventually allow humans to live for hundreds, or even thousands, of years. These transhumanist possibilities seem to be hovering on the not-so-distant horizon these days. How do you think our lives and culture would change if humans were able to live for several hundred years? Do you think most people would choose life extension? Would these technologies become a highly sought-after medical commodity in the future, similar to how cosmetic surgery is now in demand among the people who can afford it?

Whether people would choose longevity depends on so many different things. Right now, death is a relief for a lot of people. It’s the end of economic struggles, it’s the end of psychological torments and various wounds and pains. If, or when, we overwhelm scarcity and have effective treatments for the worst types of emotional and psychological pain, I think most people would want longevity. Some may not. They may find life more meaningful by allowing the body to run down and die within a limited time. The mortals may form an interesting and honorable “counterculture.”

As far as how culture would change, science fiction writers have written marvelous speculative scenarios that are more interesting than anything I could conjure up. One of my favorites is still Schismatrix by Bruce Sterling from way back in 1985. That was an incredibly hip vision – “mechs” versus “shapers.” The mechs are cyborgs, altering their bodies through hardware, and the shapers mutate themselves using biotech.

While I’m ultimately pro-longevity, because I think that it might produce worthwhile and amazing results in terms of human experience and human consciousness, my fear is that longevity will produce a risk-averse culture. Why risk your life when there’s so much life left to risk? People might be even more unwilling to confront abusive power, particularly so long as the abuse is aimed at others. Actually, I suspect that we’ve already entered into that mentality at some kind of unconscious level.

I’m curious as to how you choose the name RU Sirius. The absurdity of it calls attention to the trickster side of your personality. I imagine you’re familiar with the bizarrely synchronistic stories of popular science fiction authors Phillip K. Dick and Robert Anton Wilson, both of whom went through serious (Sirius?) spiritual revelations and began to believe they were in telepathic communication with entities from the Sirius star system. Dick’s experiences were written into the VALIS trilogy, and Wilson’s experiences were written into the Cosmic Trigger trilogy. Does the Sirius star system have some significance for you, or is the name just a clever pun?

Yes.

Or in other words, it was just a clever pun, and I’m a huge fan of Dick (heh heh heh) and Wilson, and particularly of VALIS and Cosmic Trigger. You nailed that one! But I don’t honestly have any experiences or attachments particularly related to the Sirius star system. I’m just a quippie.

Speaking of tricksters and RAW, you’re teaching a course for the late Robert Anton Wilson’s Maybe Logic academy. What sort of education does the Maybe Logic academy provide? Am I correct in thinking its a sort of pseudo-occult mystery school, based on some of Wilson’s philosophical ideas? What is your class about, and how do you teach it?

Maybe Logic Institute was inspired by Robert Anton Wilson and was set up primarily for him to teach online courses. The online institute expanded out from there, inviting people who might loosely be seen as fitting into a Wilsonian orbit to teach online courses as well. I’ve taught a few of them – I worked my “Question Authority” concept over in one of them.

A lot of the courses do have an occult/magic/witchcraft kind of theme to them. I think those are the most popular courses there, but I could be wrong. Erik Davis taught a course on P. K. Dick there and Doug Rushkoff has done a few courses, and so on.

My class is on “Pranks, Pranksters, Tricksters and Tricks.” We’ll look at the ways that pranksters and tricksters create a kind of space for psychic liberation in a world dominated by dour moralists and earnest predators – or is it earnest moralists and dour predators? Anyway, at the same time, we’ll interrogate the prankster-as-revolutionary narrative. Is it really an effective method for changing politics and culture, or is it just a great personal-existential release?

I was rather impressed with Robert Anton Wilson’s “Maybe Logic” video which was released a few months before his recent death. As a philosopher, he practiced what’s sometimes called non-Aristotelian or “multi-valued” logic – a system of logic in which multiple, seemingly opposed truths can co-exist simultaneously. This form of logic is found in the I Ching, the ancient Chinese divination book. Wilson adopted the symbol of the Sacred Chao as part of the Discordian anti-religion to show this chaotic paradox of the connectedness of opposites.

I’m particularly interested in Wilson’s idea that humans have different “reality tunnels” or limited points of view, based on our learned associations, beliefs, and assumptions about the world. Wilson notes that our brains are constantly receiving millions of different informational signals all the time, but we form our ontological understanding of the world based on which information we choose to pay attention to, and which we choose to filter out of our belief system. This is essentially a form of postmodern relativism, a philosophy which has been debated and for the most part rejected in the academic and scientific world, but Wilson makes a convincing case for it.

I find this philosophy appealing because if we believe that everyone is to some degree experiencing their own subjective reality, then it becomes a lot easier to come to a place of understanding with people who you have disagreements with. People who we would normally think of as “evil” are not evil in a morally absolute sense, but rather they are just acting as they believe they should based on their own subjective “reality tunnel.”

Have you been influenced by Wilson’s writings? What do you think of Discordianism and his other philosophical ideas?

I’ve been massively influenced by Wilson as a philosopher. You’ve said so much of what he was about so well already in your question, but let me state my main lessons from “Bob.” I think it’s clear from all of my answers in this conversation that I agree with Wilson’s dictum that “the universe contains a maybe.” I think I generally answer any reasonably complex inquiry with some sort of maybe and avoid absolute, totalistic predictions and dogmas. There’s a Wilson quote, or proverb, that I think about almost every day, particularly when I’m reading someone’s political opinion or when someone is trying to prove a point. Wilson said, “The prover proves what the thinker thinks.”

I think being aware of that, and as the result, being fairly cynical about what the prover is proving, presents a bit of a conundrum because you don’t want to fall into the trap of the Bush administration official who ridiculed the press for being in a “fact-based reality.” Right? When the government is trying to scam you into war and repression and other types of horseshit, facts matter. And when religious fundamentalists are trying to take us back to the days before Galileo or maybe even Copernicus, scientific facts and scientific methods matter. Even though facts are always, in some sense, approximate and contingent, they matter.

And I think that’s why there’s currently a hostility towards postmodernism. The times require pragmatism, and postmodernism has a tendency to crawl up its own ass. Also, people tend to confuse pragmatism with certainty; the pragmatist is presumed to want hard facts not squishy, ungraspable fluidity. In truth, certainty is the enemy of pragmatism, since it’s vital that pragmatists be open to new data that challenges their assumptions or they won’t succeed. The trick, I think, is to be able to act on fuzzy, temporary, contingent, utilitarian “truths” without turning them into big, rigid, inflexible “Truths.”

One idea I find particularly interesting in your writings is the “mutation” of humans. What exactly are you referring to here? The most apparent kind of mutation I can think of in our culture is the alteration and evolution of the mind with psychedelic drugs. There has been some research by well known authors as to how psychedelics substances have affected human consciousness through the ages. Timothy Leary developed the “eight circuit model” of the brain which links consciousness and psychedelics. In Food of the Gods Terence McKenna proposed the theory that psilocybin mushrooms altered human evolution and helped develop the neo-cortex part of the brain.

From what I’ve read, it seems reasonable to say that psychedelics have affected human biological evolution and modern culture to an extent that may be far greater than what we publicly recognize today. These “mutations” have occurred not just on a biological level, but also very much on an artistic and spiritual level. It’s interesting to see how scenes like the psychedelic counterculture, rave culture, Hip hop, local café open mic scenes, and even mainstream subcultures seem to be increasingly spiritually oriented. It seems like intelligent people are becoming more interested in compassion and collaboration rather than destruction these days. Are these the types of mutations that you’re advocating? How do you view the relationship between psychedelics and human consciousness?

First of all, of course, since evolution happens via mutation – mutation, natural selection and genetic drift – and a mutation is a genetic alteration, we can now begin to talk about self-directed genetic mutation, with germline engineering being the most obvious expression of this possibility. It’s something that has already been done in animals. So when I talk about mutation, in some sense, I’m really talking literally about mutation. I’m talking about freaking freely with our corporeal bodies and brains: “Maybe a tail would be nice.”

On another level, this word mutation, or “mutant,” has been out there as a meme since the mid-1960s, when the organizers of the Be-In declared the hippies a new generation of mutants. Frank Zappa formed “United Mutations,” Timothy Leary started using the term to define the “post-Hiroshima generation,” and so forth. So there was this sense of newness, of otherness in “freak” culture; nobody quite knew how we could or would mutate, but it seemed to involve the ways that our perceptual apparatus was being made different by psychedelic drugs. The new technologies as defined by McLuhan (who told us that we were a whole different type of human being) and the opportunities that economic privilege allowed us to search for different ways of living. Or a way of escaping P.K. Dick’s “black iron prison,” or whatever (it was all fairly inchoate). Of course, that sense of positive alienation had a limited shelf-life. We were human, all too human, after all.

Finally, yes, there’s this group evolution or mutation that seems to have grown out of the counterculture – a new and possibly evolutionary, collaborationalist mind-meld that’s expressed by these hip subcultures you mentioned (and also by Wikipedia, even by the way Google works, and so forth.) And psychedelics and empathogens like ecstasy seem to be playing a role in this emergent mind-meld.

I’m not enough of an anthropologist to comment on the role of psychedelic plants in the evolution of human consciousness up to this point. They clearly have played a role in contemporary culture and seem to have played a role in our understanding of DNA – at least they seem to have inspired Sir Francis Crick. They played an important role in the evolution of thinking machines, as documented by several recent books. They’ve played a role in preparing us for the “neuro-age,” in which we will hopefully have chemical and other types of control over (and access to) our brains for performance enhancement and problem-solving, bliss, perceptiveness, emotional intelligence, and so forth.

Finally, it may be all about feeling really good at a really highly evolved level, you know? It’s like, when I go to a Singularity or a Transhumanist conference I’m always left with this feeling: yeah great, we can get incredibly smart, live long and process incredible amounts of information. Hell, we can even seed the galaxy with information processors, but what the fuck is it all for? And maybe what it’s all for is this intimation or message or sense that some of us have gotten from psychedelic experience that expanded, enhanced human consciousness liberated from the mundane is at once peaceful and exhilarating. And indescribably ecstatic. It’s all about the Agape, stupid.

* * *

Tune in to RU Sirius’s podcast radio show, and check out his social newtork website, Mondo Globo.