A radiant morning sun shone warm and bright on my face, and a feathery breeze teased my hair as it blew across the high desert. The air smelled fresh and clean, redolent with sweet, delicate fragrances of dried flower blossoms on small bushes and the mild aroma of sticky creosote being coaxed out of the chaparral by the warmth of early spring. The last week of March was still early for the yuccas, spidery ocatillo, jumping cholla and opuntia cactus, which were just beginning to burst forth with their floral profusion. But the wildlife was out in full force, and the desert was teeming with living creatures, from yucca night lizards to kangaroo rats, sidewinders, tarantulas and stinkbugs.

I was taking a week off prior to a business trip to hike and photograph some of the medicinal plants in the high desert of southern California. No phone, no to-do list, no meetings. I welcomed the solitude, the peace, the distant removal from frenetic civilization. The first night of my stay I had a wild, tangled dream of howling ghosts and phantoms rising up out of a basement shaft. They swirled and yowled, whooshing up into the atmosphere. Expurgations of the deep psyche? Post civilization stress syndrome? I awoke to buzzing bees, chirping birds and the rustling leaves of bright green oleander bushes in the morning breeze.

I stayed just outside the western entrance to Joshua Tree National Park, at the Institute of Mentalphysics, a spiritual retreat center built in the 1940’s according to the visions of a man named Ding Le Mei, who had learned unusual yogic methods while mapping territory as a surveyor in Tibet. I had lived in a small farm house at the northwest corner of the center for about a year in the late 70’s, and the place felt like home. After a long, limbering yoga session I drove my rental car into the sleepy little one horse town of Joshua Tree and ate breakfast at a comfortable hippie dive whose garish, hand painted day-glo green and orange roadside sign advertised cappuccino, beer and healthy food, in that order. A smiling brunette earth mama named Kathy served me a Depth Charge — two shots of espresso in 16 ounces of strong coffee, and a big bowl of crunchy granola with chopped apples. Thus bio-fueled with calories and caffeine, I felt ready to ramble the mysteriously lunar landscape of the area.

After breakfast I enjoyed a leisurely walk along a flood wash, a wide dry river bed that holds no water, except when there is a rare heavy rain. There were big jackrabbits with absurd, huge ears, bounding across the chaparral like kangaroos, and smaller, nervous cottontails hopping and scurrying away in response to the slightest odd sound. I saw lizards and road runners and quail, and watched one very large gray hawk soar off the top of a Joshua tree and glide on an invisible thermal current up and over a distant hill and out of sight. Songbirds chirped and called to one another in high pitched exuberance. On a ridge I observed three coyotes trotting together. Observing all the wildlife infused me with a great sense of wonder.

Around mid day I drove out into Joshua Tree National Park, a hiker’s and rock climber’s paradise, for a long trek into the hills to observe and photograph medicinal plants. I seemed to have the entire desert to myself. The area is dramatic and majestic, a half million acres of protected open space with an exciting diversity of terrain, vegetation and wildlife. There are palm oases, arroyos, and rugged mountains with crenellated, rocky slopes that drop thousands of feet. Long ago, Pinto Man, among the earliest inhabitants of the southwest, hunted and gathered there. Later the Serrano, Chemehuevi and Cohuilla Indians harvested cactus fruit, acorns, mesquite beans and pinyon nuts in the area, leaving behind basket pieces, pottery shards and rock paintings to mark their passing. Miners in the 1800’s built dams and dug mine shafts. There are still remnants of the Desert Queen and Lost Horse mines. Horse thieves kept stolen mounts in Hidden Valley. I could imagine hard riding men with leathered faces driving their mounts into the remote places of the area, camp fires at night, pistols on every hip, danger in the air.

I spent the following three days climbing and hiking out in the vast park, following long trails to mountain tops, abandoned mine shafts, and surreal landscapes filled with thousands of awkward, spiny joshua trees, many of them hundreds of years old. While the air in the valley conveys the fragrance of chaparral, out in the monument the perfume is pinion pine and juniper, with occasional whiffs of animal scat, fetid snake holes and sweet floral scents. Even though the trails were well trod and marked, I felt as though I was wandering past time and history out there, treading with each step further into a dimension of raw natural power, leaving all traces of civilization behind. The rugged, rocky terrain hosted a profusion of animals and plants. The desert lay under the spell of a vast, haunting silence, and I could hear my own heart beat.

Along the Eagle mountains in the southeastern region of Joshua Tree National Park, I photographed early blooming flora, including large white blossoms of gnarled, spiny joshua trees, yellowish, waxy blossoms of Mojave cactus, and stunning magenta flowers of needle-sharp hedgehog cactus. I shot several beautiful specimens of prickly-pear and beavertail cactus, both of which were foods of the early peoples in that area. Along the way I spotted red-tailed hawks perched on joshua trees, antelope ground squirrels nibbling carefully at the flower buds of prickly cholla, a Costa’s hummingbird sipping the nectar of ocotillo blossoms, and a leathery chuckwalla — a prehistoric-looking reptile, sunning itself on the top of a large slab rock.

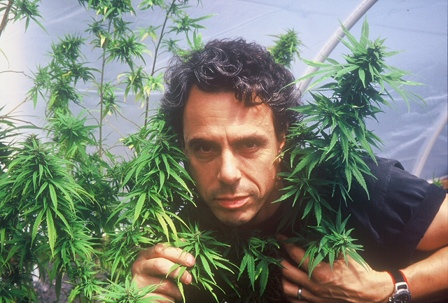

On the fourth morning, I awoke feeling prepared for an experiment I had planned. For many years I had maintained a strong interest in sacred, psychoactive plants. Used as sacraments by numerous cultures around the world, sacred plants are considered keys to a luminous reality, a spiritual realm that others call the kingdom of heaven. I had practiced yoga daily for over twenty years, and was familiar with a variety of non-ordinary states resulting from deep meditation and focused practice of various yoga methods. But I also knew that the judicious use of psychoactive plants could quickly deliver a person to many of the states that took a long time to achieve through these practices. I had brought to the desert with me a chick pea-sized ball of Nepalese black hashish, which I intended to eat. Hashish is the concentrated, pure resin deriving from the flowering tops of cannabis. For while smoking cannabis produces a high state, eating cannabis, especially in its most concentrated form as hashish, can produce a greatly more intense and revelatory experience. I had read various accounts of hashish eating from Hindu and Arabic texts, and in European literature. One to another, they portrayed vivid journeys into fantastic spirit realms, and a sense of the immanent presence of the divine. I wanted to find out for myself. I wasn’t the least bit interested in getting stoned, and hadn’t done so since my first year in college. But I was greatly interested in breaking through the veil that separates this phenomenal world from what Carlos Castaneda so aptly referred to as a separate reality. I counted on this “bio-assay” to show me if such a breakthrough was indeed possible.

Through my many years of intensive daily yoga practice and meditation, I had developed an easy talent for achieving serene states, for stimulating internal energy flow, and for accessing unusual realms of consciousness. Yet I was aware that another set of tools, pulled from another magic hat, if you will, existed for such attainment. Hundreds of accounts suggested that such a possibility was likely, and that sacramental plants such as hashish, peyote, San Pedro cactus, and the fabled Amazonian brew ayahuasca, every bit as intrinsic to nature as ourselves, provided keys to the conscious and spiritual locks within us, and offered express passage to other worlds. Many people further claimed that these plants were not simply chemical transporters, but fully conscious allies in such pursuit. There was no reason to imagine that the sages of the east held all the answers to spiritual exploration. Other people in other lands had also engaged in deep explorations of a spiritual nature, utilizing other methods. Could I use the hashish to, as the hit song by the Doors put it, break on through to the other side? There was really only one way to find out for sure. Swallowing the material and letting it take me where it would was the short path.

My choice of hashish as an agent for journeying was by no means random. I knew from a great deal of research that hashish possessed the power to produce a full and significant psychedelic experience. Coined by psychiatrist Humphrey Osmond, the term psychedelic literally means soul manifesting, or mind-manifesting. The psychedelic agents in nature all possess the ability to provoke powerful expressions of mind, and a deep sense of inter-connectedness with all things. It is the latter effect that so faithfully reflects teachings in both yoga and Buddhist thought, of everything being one and indivisible. As an agent of consciousness modification, hashish enjoyed thousands of years of use. Many yogis claim that the god Siva himself provided cannabis, its source plant, to humanity, so we could commune directly with the divine.

Despite the best efforts of botanical experts to pinpoint the exact origin of cannabis, this information remains elusive. There is general agreement that Cannabis sativa is native to central Asia, north of the Himalayan range. Cannabis sativa is the name given to the plant in 1623 by botanist Caspar Bauhin. The name means cannabis — “cane-like” and sativa — sown or planted. Throughout time many botanists have maintained that all cannabis plants are Cannabis sativa or sativa sub-species. But Russian botanists as well as Drs Richard Evans Schultes and LSD discoverer Albert Hoffman assert that there are two other distinct species, Cannabis indica, or so-called “Indian hemp,” and Cannabis ruderalis. Cannabis sativa tends to be a taller plant whose branches start higher up on the stalk. Cannabis indica is typically shorter and more densely branched. Cannabis ruderalis is short and sparsely branched. Of these, Cannabis indica is most consistently of high potency as far as psychoactivity is concerned.

For most users, cannabis delivers an expansive, spacious high. For many, cannabis heightens sensory experience. It makes music more rich, food more tasty, colors more vivid, touch more sensual, sex more erotic. In some people, cannabis stimulates creativity. In many, it provokes laughter. “Taken moderately, hashish cheers a person’s mind, and at most, perhaps, induces him to untimely laughing. If larger doses are taken, producing the so-called fantasia, we are seized by a delightful sensation that accompanies all the activities of our mind. It is as if the sun were shining on every thought passing through our brain, and every movement of our body is a source of delight.” –Dr. Jacques-Joseph Moreau

Cannabis plants grow between 1 and 20 feet in height, with a furrowed central stalk from which numerous branches grow. The branches are covered with green leaves with long, green toothed blades. Virtually all parts of the cannabis plant above ground are covered with trichomes, fine hairs. Among the various types of trichomes, those known as capitate glandular trichomes contain a resin rich in cannabinoids, the phytochemicals which produce the distinctive psychoactive effects of this plant. Of these, over 70 are currently known. Cannabis plants are either male or female, and the difference between the two becomes most apparent at the onset of flowering. Males flower prior to females, and pollinate the females as they flower. Then the males begin to lose vigor and wither, while the females prosper and thrive.

The flowers and leaves of cannabis plants are used to smoke, to eat, or to make hashish, which is the concentrated resin. Flowers have a greater number of resin glands, and are thus the most prized parts of the plant. Leaves of both male and female plants contain comparable levels of cannabinoids. But the flowers of the two sexes differ greatly. In high quality cannabis, male flowers can produce a high. But in lower grades, they may not do so at all. Female flowers, however, will be resinous and will produce a high. For this reason growers apply their best agronomic efforts to increasing female bud size and yield, as well as potency.

Cannabis produces its satisfying and euphoric effects thanks to the cannabinoid THC, or tetrahydrocannabinol, which is found in the resin which accumulates in cannabis leaves and flowers, and which determines the potency of the material. THC binds to specific receptor sites in the brain, producing euphoria and relaxation. The acute toxicity of THC is extremely low, and there has never been a single reported case of a death due to THC or cannabis consumption in any form. THC is lipophyllic, and thus mixes well with various oils. For this reason, THC is readily dispersible in butter and other fats used in the making of cannabis baked goods and confections.

Cannabis is well-loved and widely employed by hundreds of millions of people worldwide. Thus it is no surprise to discover that the brain is uniquely fitted to accommodate the active constituents of marijuana. In August 1990, researchers reported in the journal Nature the discovery of receptors in the brain which specifically accommodate the cannabinoids in pot. Cannabinoids bind to particular neurological sites in the brain, as though the brain was specifically designed to utilize this plant. Did nature toss cannabinoid receptors into the brain by random chance? Are these physical structures accidental neurological junk? Or are cannabinoid receptors part of an intelligent design for deriving maximum benefit from cannabis? Is cannabis a divine elixir of sacred communion for which we are ideally suited?The most potent and concentrated form of cannabis is hashish, which is the pressed resin glands of mature female cannabis flowers. When cannabis is mature and the buds are sticky with pregnant resin glands, then hashish can be made. This is performed by various methods. In the Himalayan foothills of India and Nepal, collectors run their hands up and down against the resinous flowers of mature plants, until their palms are covered with resin. They then rub their hands vigorously together to clump the resin into little balls. These little balls are rubbed together into larger balls, or into “fingers” of a regional hashish called charas. This charas is fragrant and sweet, with a floral aroma, and conveying a pleasant, lively high. As romantic as the hand-rubbing method of hashish production may seem, it is very inefficient, and really only suitable for those instances in which there is a large amount of ganja available. This is certainly the case in the Himalayan foothills, where the yards of most homes feature a plot of cannabis for charas, hemp fibre and nutritious seeds for cooking. The people in that region enjoy a super abundance of high quality cannabis.

For the most part, hashish is made by sieving. In this method, ripe cannabis plants are harvested and dried, usually by hanging them upside down. When the plants are reasonably dry, they are then shaken or lightly beaten against a fine sieve, through which the tiny resin glands fall. This results in a pile of fine, dust-like resin which is highly maleable and easily molded at room temperature. The resin may be rolled into balls by hand, hammered into concentrated blocks, or mechanically pressed into squares. Some hashish is even stamped with a seal of origin.

Some old methods of hashish manufacture involve rubbing the plants against coarse carpet before sieving, or sieving through fine cloth. The important part of the process is that as much resin as possible is collected, and after that, any pieces of leaf or other debris are removed by the sieve. Fine quality hashish is free of debris, contains no mold, is uniform in color and texture, and is malleable in the hand at room temperature.

Different types of hashish come from different regions. The legendary Nepalese Temple Ball and Manali cream varieties are both black and smooth. Hashish from the Bekaa Valley in Lebanon is often red. Most Afghani hash is greenish-brown. Some Middle Eastern hashish is blond or pink. Whatever the type or the origin, the goal of any real quality maker of hashish is to produce a uniform product made solely from resin glands, to ensure purity and potency.

Hashish is either smoked in a pipe, or eaten. As a smoke, it is typically pleasant and lofty. As an eaten material, it can be wildly powerful. For this reason, the eating of hashish should be approached with care and caution. All things considered, hashish is the cognac of ganja products. Throughout much of India, Nepal, Kashmir, Turkey and the Middle East, hashish is the preferred form of cannabis. This is owing to its rarified nature and exquisite effects.

Cannabis has most likely been a companion of humans since the advent of agriculture, around 10,000 years ago. The Chinese emperor and revered herbalist Shen Nung wrote about cannabis in 2000 B.C., recommending its use for rheumatic pain, constipation, constipation and female disorders. The emperor commented that cannabis “makes one communicate with spirits and lightens one’s body.” In early China, cannabis was used in magical ceremonies for divination. Later around 200 AD, the herbalist and surgeon Hua Tuo employed cannabis in wine as an anaesthetic.

In India, cannabis fit well into the traditional folk medicine. The plant was referred to in the ancient Artha Veda, which may have been written as early as the treatise by Shen Nung. The plant was recommended for a variety of health needs, from relieving dysentery to improving digestion, easing headache to improving judgement. The Rajanirghanta, penned around 300 A.D, recommended cannabis for alleviate flatulence, stimulate appetite and boost memory. The later Tajni Guntu described cannabis as a strengthener, a promoter of success, a mover of laughter, and a sexual excitant. In the Hindu tantras, cannabis was described as an empowering intoxicant. The plant was made into “pills of gaity.” Its psychoactive properties gave cannabis high status, as a divine elixir, a life-promoting, soul-vitalizing agent. In the Indian Himalaya and the Tibetan plateau, cannabis achieved high religious esteem.

Cannabis has traveled far and wide, carried on the backs of pilgrims, traders, and sailors. One historical account states that in ancient times an Indian pilgrim introduced cannabis use to Khorasan (northeastern Iran). From there, cannabis spread to Chaldea (southernmost valley of the Tigris and Euphrates rivers), into Syria, Egypt and Turkey. Hair analysis of Egyptian mummies dated back to 1070 BC reveals high levels of cannabis residues. This puts the spread of cannabis into Egypt prior to that time. Early Arabian manuscripts describe the Garden of Cafour near Cairo as a major location for the use of hashish by fakirs.

Sometime around 450 B.C. the Greek historian Herodotus recounted the use of cannabis by Scythian horsemen in central Asia. The Scythians lived in an area now known as the Siberian Altay. I have been there myself, and have seen vast tracts of cannabis stretching out over hundreds of miles in that region. The Greek writer said “they make a booth by fixing in the ground three sticks inclined towards one another, and stretching around them woolen felts, which they arrange so as to fit as close as possible: inside the booth a dish is placed upon the ground, into which they put a number of red hot stones and then add some hemp seed…. The Scythians, as I said, take some of this hemp-seed, and, creeping under the felt coverings, throw it upon the red-hot stones; immediately it smokes and gives out such a vapor as no Grecian vapor bath can exceed: the Scyths, delighted, shout for joy…” The account given by Herodotus has been confirmed in archaeological digs, with the discovery of apparatus as described. However, to correct the record of Herodotus, residues show that cannabis leaves and buds were the materials which produced Scythian euphoria, not the seeds. The Scythians took cannabis, their joy-giver, across Asia westward to Europe. An urn found in Berlin and dated around 500 B.C. contained cannabis leaves and seeds. Within a short period, cannabis had made its way to England, Scotland and Ireland.

Archaeological evidence shows that the Assyrians used cannabis for incense during the first millennium B.C. Hashish especially became popular, spreading throughout Asia Minor during the first millennium A.D., and from there into Africa. Tribes-people in Africa, notably the, Bushmen, Kaffirs and Hottentots (who called cannabis Dacha ), embraced the euphoria-producing effects of cannabis. The plant and its use were taken up enthusiastically throughout Africa.

In the 13th century, Marco Polo recounted the tale of the hashishan, or assassins, who were followers of a mysterious “Old Man of the Mountain.” According to history, the warlord Hasan ibn al-Sabah, resided in the mountain fortress of Alamut, south of the Caspian Sea. Hasan ibn al-Sabah reputedly intoxicated young recruits with hashish, and indulged them with women and all manner of pleasures. Informing the soldiers that such rewards would be theirs as a result of unwavering service to him, he garnered extreme loyalty among his troops. The young hashishan were bold, fierce, fearless, and willing to sacrifice themselves for their leader’s cause, assured of a hash-intoxicated and highly sexual idyllic afterlife. The assassins spread throughout Persia and Syria, and became a much feared sect. Marco Polo traveled along the fabled pan-Asian “silk road,” where he saw many marvelous things. I have been on part of that route, in the far northwestern Autonomous Region of Xinjiang, a Uighur-inhabited territory of China, where cannabis grows in super-abundance. From the eastern capital of that region, all the way west along the verdant Borohora Shan, along the fabled Naladi Grasslands, all the way to the rugged and majestic Tian Shan mountain range, cannabis is the single most abundant plant in sight. It is literally everywhere.

Cannabis may even have been mentioned as pannag in the Bible, in Ezekiel, Ch. 27 v. 17. Pannag is linguistically similar to the Sanskrit bhang. Are the visions of Ezekiel the psychedelic results of cannabis consumption? It is not preposterous at all to imagine that when Ezekiel saw a giant wheel in the sky, he may have been under the influence of a potent psychoactive plant. In Jerusalem, remains of burned cannabis show its use there around 400 A.D.

The morning of my planned hashish journey, I hiked from Cottonwood Spring out to Lost Palm Oasis, a recondite, isolated stand of shady palms nestled in a small arroyo. Once there, I sat in the cool shade of a tall rock, with the unceasing desert breeze tickling my face. I unwrapped the ball of hashish and chewed it thoroughly with a small handful of dried apricots and some water. And then I waited. Within half an hour I began to feel expansive, as though my physical and mental boundaries were melting away, dissolving into the desert breeze. A short while later I began to hear a faint buzzing sound in my head which steadily grew in intensity, until it seemed to come from all directions at once. The buzzing grew increasingly intrusive, and eerie in its loud volume, enveloping me. At first it sounded like one huge cicada, then like several, then like the amplified buzzing of millions of locusts. I stood up to walk, but didn’t make it very far. The sound seemed to press down on my body, a heavy atmosphere pushing me down. I was overcome by the irresistible pull of gravity, and felt compelled to lie down on the sand, stretching out on my back. I felt alternately ten feet long, and too spacious to determine my own form. My entire body and mind vibrated with the buzzing sound, which enveloped me and pressed me into the ground. My mind was strangely disengaged and slowed down, and I mused lazily to myself that I hoped everything was alright, and that no wild animals would hurt me in my disadvantaged condition. I began to dissolve, a human grain of salt dispersing in the vast waters of time.

Behind closed eyelids I viewed the vaulted mysterium tremendum of space. Elaborate geometric patterns undulated in my field of vision, a spectacle of brilliant fractals and forms in luminous, shimmering colors. After an undetermined period of time on the ground, I felt a strong urge to move my bowels. But as though I was pinned down by a gigantic weight, I couldn’t get up, and it occurred to me that I would defecate in my pants. Then the sensation changed curiously, and what initially felt like a bowel movement was something else, forcing its way slowly up the inside of my lower spine. I had the distinct feeling of a round, smooth object about the width of a wooden rake handle pushing up my lower spinal canal. As the sensation urged upward, the loud buzzing shifted, replaced by a single, high-pitched whine of extraordinary intensity. I imagined that the whine was vibrating the sand all around me, pulverizing it into fine dust which then dispersed up into the air, scattering shimmering particles to the far-flung reaches of space. The world was disintegrating.

The sensation in my spine continued, and when it reached the middle of my back I “saw” a dark, shiny snake slithering forcefully upward through my spinal canal. Oddly, the knowledge that a snake was rising up my spine was comforting to me. Was this the kundalini, the so-called serpent power, whose arousal and full awakening is a goal of yoga practice? When the snake forced up into my neck, the pressure became extreme, as if the snake was too wide and was cracking the bones of an internal passage that was too small. I mused that perhaps giving birth felt something like that. The serpent just kept rising, steadily and smoothly slithering up into my brain, producing an aching pressure. I thought my head would split from the pressure. The volume of the high pitched whine intensified to a thrilling, overwhelming pitch. The entire world whined.

When the snake reached the top of my head, it strained against the inside of my skull and cracked through the bones. I felt tremendous relief, and took a long, sighing breath. Once outside my skull, the snake elongated and fanned itself wide like a huge, hooded cobra. It raised its head high, eyes glittering yellow, mouth open and razor fangs sticking out. Then in one deft strike, the snake drove its fangs into the center of my forehead, causing a blinding pain that seized every muscle in my body and made my ears pound. I thought that my bones would crush from the tension. Then as quickly, the snake yanked its fangs from my forehead.

The whining sound changed again, increasing to tornado intensity in my skull. Dozens of distinct sounds roared, blared and howled, each one louder than the most violent storm. As the sound current increased far past what I imagined possible, an electrical vibration coursed throughout my entire body, causing all my molecules to dance wildly. My interior was unimaginably vast. A roaring current of sound surged from my feet up through my head as loudly as if a train was hurtling over my body. Every cell of my body was being pulverized by energy. Up through the center of my spine a wailing current of almost unbearable intensity coursed. The roaring sounds and raging sensations were accompanied by a stunning display of vivid colors, brilliant jets of gold, yellow, red, blue, purple and silver surging upward through my body, clearly visible to my interior sight. I was suffused with undulating waves of rose and blue color, and streaks of pure, clear white light, which coursed through my entire body. The energy and colors surged through me, bathing every cell in my body, dissolving all thoughts, questions and ideas, stripping my mind clean. Tabula rasa.

Before me, an immense, yawning tunnel gaped open, the pupil of a gigantic eye, bigger than the ocean, bigger than the sky. The last remaining tiny bit of my self identity ripped up and out of my body. As if launched by a gigantic catapult, “I” hurtled upward into the vast heavens, through the center of the great eye and into a blazing realm of fire. Flames raged above, below, before, behind. I was consumed in fire. And there before me, resplendent, magnificent, beyond all comprehension, spirits and forces of antiquity rolled on by my field of vision. All around me streamed waves of radiant light and blinding orange fire. The entire universe, and all that is known and unknown, collapsed and was obliterated by the flames.

Several hours later in the cool desert dusk, I rose alert and hungry. I stood, shook the sand off my pants, and looked out at the San Jacinto mountains. Visible waves of blue-white energy streamed over the peaks. I smelled the delicate honey scent of blossoms far away, and heard lizards crawling on the palms. High above the oasis, a hawk dipped in a long, graceful ark. I watched it until it was gone from sight, flying over the mountains without once flapping a wing. I gathered my thoughts as best as I could, slowly taking in what had transpired. Everything about me felt more alive. My senses were keener. My mind felt burnished and radiant.

Most of us, to some extent or another, intuit the presence of greater or divine power. Some call it God, some The Great Spirit, some The Creator. Cults and religions apply various names and descriptions. Pundits, intellectuals and priests argue over its nature. Religions claim special relations, and offer to negotiate with this power on our behalf, petitioning for our “salvation.” We get a sense that this power suffuses creation, provides an ocean in which we swim. And yet, for most, spirit remains an abstract notion, something beyond our experience, something we invoke in times of stress and crisis. We may yearn for more, but few receive it. Religions are often dry wells that pass on tales of mystic experiences, but only as relics of the past, attainable by bearded others in antiquity, but not by us.

Yet others, carrying forth vibrant archaic practices, have found ways to encounter spirit directly. Their charging mounts are meditation, drumming, dancing, mind-bending rituals and sacramental plants. Employing these as if riding on furious steeds, they crash through the guard gates of the luminous reality in which this power can be encountered. These methods provide an all-access, backstage pass to the spirit landscape.

In one of my favorite yogic scriptures, the Rosary of Gampopa, it is written that “circumstances arise from a concatenation of causes.” Try to identify the origin or source of something, and invariably you will find strings that when pulled lead to other strings, and that when pulled lead to yet others. The smallest moments, conversations, events and scenes aggregate like microfibrils, twisting into endlessly varied threads, that weave into the fabric of our lives. The design, patterns and colors of each life are unique, born of trillions of such concatenations, reaching back to the beginnings of time. In fact, we can never find the beginning of anything, as there is always someplace further back to go. But I can say nonetheless that the incident at Joshua Tree quickened my interest in other practices beyond yoga, and traditions that utilize not only cleverly constructed ceremonies, but psychoactive plants as gate-crashing agents for gaining access to the spirit world.