This article is excerpted from the memoir Ayahuasca in My Blood–25 Years of Medicine Dreaming.

I started traveling to Peru and had my first ayahuasca experience in 1984. I returned in 1985 to begin jungle survival training with a former Peruvian military jungle specialist named Moises Torres Vienna, his son Junior and an associate, Mauro. Moises introduced me to the man who became my healer and great friend, Julio Jerena. Julio was an elderly curandero who lived on the Aucayacu River, about 200 km upriver from Iquitos. At the time it was a pretty isolated place. For me it was worth the trouble to get there because spending time with Julio was always fascinating. His knowledge of jungle medicines, his compassion, his simple life as a fisherman never failed to impart important lessons to me. I simply loved being with him and his family.

This particular story took place in 1988. At the time, I hadn’t drunk ayahuasca since 1986, when I’d had a very powerful experience of associating with a large snake. In the year and a half since that experience, I made several trips to the Aucayacu during which I didn’t use ayahuasca. Not that part of me didn’t want to, it was simply too powerful to use unnecessarily. I still didn’t understand the concept of talking with plants or communicating with the spirit world, but I’d lost what remained of my skepticism and knew that it was not something to be played with. When the appropriate time came for me to use it again, I would know it.

That time came in the summer of 1988. Moises and I took a long jungle trip — one that saw us walk across the Peruvian jungle to the Yavari River, the border between Brazil and Peru. The journey ended with a three-day ferry ride from Leticia, Colombia, back to Iquitos. Among the people onboard was a Peruvian named Roberto whom I’d known off and on for years. As his game was bilking tourists for phony environmental causes and I was a tourist, we weren’t close. Still, we talked occasionally.

“Hello, Peter,” he said when we both found ourselves at the ferry’s refreshment stand. “Have you done any ayahuasca lately?”

“No.”

“There’s a fantastic curandero now living in Pevas you should see. I’ve taken lots of tourists. What visions they have! Much better than that old man you see. Maybe I’ll take you.”

“Thanks, Roberto. No need.”

“Well, then, have you heard about the ayahuasquero fight?”

“No.”

“You probably don’t know anything about them.” He went on to explain that many ayahuasqueros used their spirit connections to accumulate personal power or wealth, frequently by making bad things happen to people at the behest of their enemies–what is called brujeria. The brujeria needed to be countered by a curandero working for the good, which supposedly led to great battles between good and evil ayahuasqueros. Those battles were said to be fought with invisible arrows called virotés, which could inflict great physical harm or even death. I’d heard something about those battles somewhere but had never believed they were taken seriously. Not that the idea of witchcraft seemed improbable, it just seemed more complicated than necessary.

“Well,” Roberto said, drinking a beer I’d bought him in exchange for his story. “One ayahuasquero in Santa Clara has been slowly poisoning another in Iquitos. Very well done. By the time the man in Iquitos realized his illness came from virotés it was almost too late. Fortunately, one of his sons has been studying with him and now he too is in the fight. Everyone says that all three of them will be dead before long. Now that’s a story, eh?”

While I acted skeptical at the time, when we reached Iquitos I made plans to see Julio to ask him about this aspect of the medicine. I had no real intention of asking him to make ayahuasca for me, but while I was still in Iquitos I had a dream which changed my mind. It was about my father, Tom, who had been dead for nearly 16 years at that time. In the dream he told me that he could no longer see my mother–also dead several years–and asked me to find her and find out why. It was an eerie dream and I decided to use ayahuasca to try to discover what it meant. I don’t know what I expected, or whether it was just an excuse to use ayahuasca again, but it made sense to me that that was what I should do.

I brought along a friend from Iquitos who had never been to the Aucayacu, and at the last minute discovered that Moises had found four tourists who would also be going. Junior and Mauro would be accompanying them–Moises did not come–which made our party enormous. Worse, when Moises learned that my friend, Jarli, and I were planning to use ayahasca, he immediately sold the idea to his group.

Despite the size of our party, the time we spent on the little river was glorious. Mauro and Junior took care of Moises’ gang, while Jarli and I were left to our own devices. I was saddened to learn that Salis, Julio’s apprentice, had been killed in a dispute with a Matses man, one of Papa Viejo’s sons. It seems that Salis had been recruited by one of the big tour companies operating out of Iquitos to offer ayahuasca once a week to large groups at a camp just outside the city. It had evidently gone to his head that he was important and when back on the little Aucayacu he took advantage of his position and money to seduce some of the women there. Among them was a young Matses woman, the main wife of a Matses man named Antonio, who, like Salis, had been my friend for a couple of years. The seduction occurred while Antonio was out in the jungle hunting for a few days. When he returned and was told of it, he put a shotgun to Salis’ belly and fired, then headed off with his wives and children to Brazil.

When I raised the subject of the invisible arrows with Julio, he was at first reluctant to discuss it. And even when he finally agreed, he prefaced his remarks with the comment that I wouldn’t really understand what he was talking about.

“This is not something for people to talk about,” he said, “so I won’t say too much. You ask if there are spirit arrows–of course. When I was younger and still in Pucallpa there was a brujo there who hated me. At first he used them on my house and chickens. I would come home from fishing and find everything in disarray, or some chickens dead. Healthy chickens he killed with his invisible arrows. And then he began to use them on me. One day I could no longer walk. I stood at my table and just fell over.”

“What happened?” I asked.

“When I could walk again I went into the woods to talk with the plants. I didn’t know what else to do. I really thought he was going to kill me. There I found this.” He took out a small stone axe-head. It was very old and perfectly crafted. I’d seen it before but didn’t know anything about it. “This is from the Incas, the ancients,” he said. “It has a lot of power. It saved me from that brujo.”

He stared at me to see if I understood. I didn’t.

“I said you wouldn’t understand. Look, ayahuasca is a strong medicine. That is why we call the four colors in our song: red, green, white and black. Each represents a different kind of magic. Some people practice all of them. But if you concentrate only on one there is no balance and the magic can take you over. Some people fall in love with money, or power or women. All different things. But they do not control the magic that brings those things, the magic controls them. Entiendes? Understand?”

Again I shook my head.

“Ah, Pedrito…Everything has a spirit. This house, these trees, the river, the fish in the river. Ayahuasca helps you reach those spirits. But when people learn to work with those spirits there is a temptation to forget that they are only the doctor, not the medicine, and they lose their balance. They are the ones to watch out for. Muy peligroso. Very Dangerous. They are drunk with power.”

I’d never heard Julio speak so much, and though I knew I’d missed a great deal of detail with my weak translation, I was thrilled. I still didn’t really understand the concept of virotés, but I didn’t press him further.

Before I left I asked if he would make ayahuasca the following night. He asked for how many and then why. I told him about my dream.

“You’ll have to go to the world of the dead,” he said. “Muy lejos, very far. I’ll make it strong.” He said it plainly, as though it wasn’t much different than taking the ferry to Iquitos.

By dawn we could hear the sound of Julio chopping wood for the ayahuasca fire and that evening at eight our whole group set off on the short walk from the small house to Julio’s. All but Junior and Mauro sat in the circle around the blue plastic sheeting on the porch. We sat quietly for an hour before Julio brought out the ayahuasca, began to chant, then passed the gourd.

I had spoken to the others about what they might expect but as they drank they were on their own. When the gourd reached me I almost choked getting the ayahuasca down. It was thick and still warm, tasting of burnt grapefruit and dank smoke. I knew I would vomit easily and soon.

Julio’s chanting was clear and strong. I suddenly leaned for the edge of the platform to retch. Violent empty bursts swelled and pulled deeply from within me. In the back of my head I could hear the words Julio sang, “Limpia, limpia, cuerpocito, cuerpocito…” urging my body to cleanse itself. Over and over my stomach contracted tumultuously. The sounds seemed to come from a far place, echoing from across the river, water cascading onto stone. I’d never felt that kind of power course through my body, and though I was utterly helpless I felt fantastically strong.

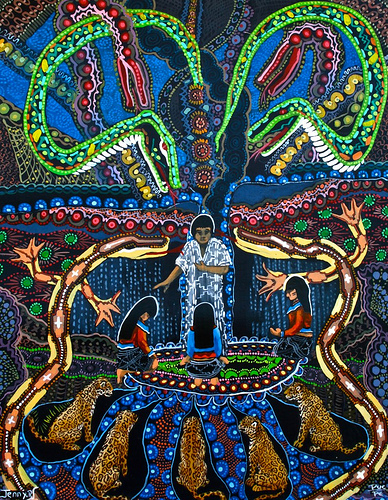

When my stomach settled, I closed my eyes. All around me were insects, visions of marching insects crawling over me, alternately tickling and annoying. As in a movie, the insect wings became the scales on a boa so broad and long I could only see a small portion of it at one time. The snake was undulating gently, slowly. In the black pitch of its scales glinted a hundred hues of red and blue. I was mesmerized. It turned its head to me and flicked its tongue. Its eyes, almost as large as the scope of my vision, were a fine black and yellow. Its underbelly was strong and white.

In an instant the serpent changed its size to normal dimensions and we moved underwater. Eels and boas swam gracefully amid rocks. I followed their motion and tried to swim with them. I was awkward and ungainly and they ignored me.

The sound of vomiting brought me back to the porch. One of the others, a British fellow named Mark, was leaning over the platform’s edge and retching violently. He tried to stand and I reached to calm him. He told me he was about to shit; I tried to help him but could hardly find my own footing and called to Junior to lend a hand. One of the others was beginning to get ill as well.

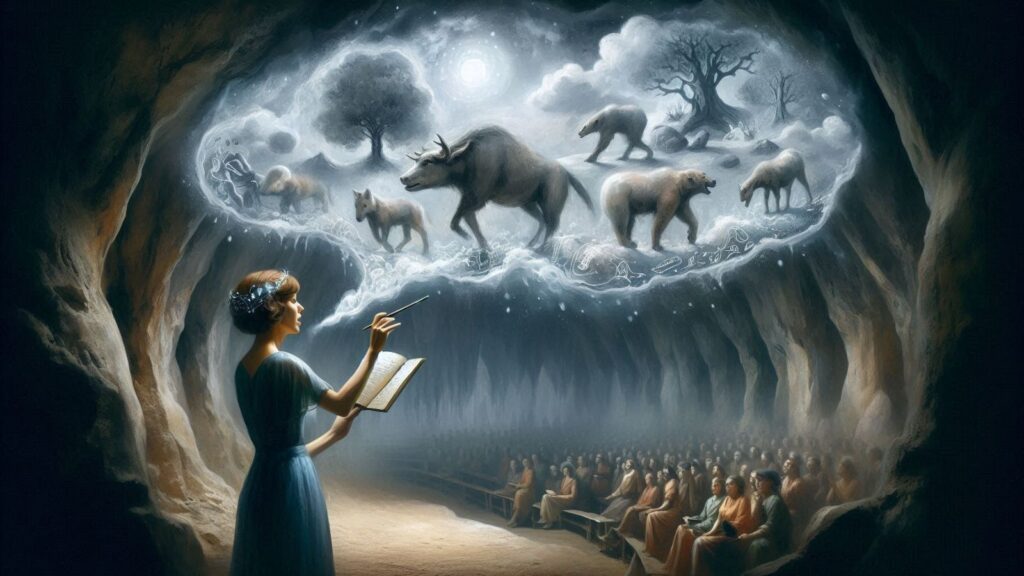

I closed my eyes again and thought about the dream I’d had. Suddenly I felt myself moving. I wasn’t with the snake and I wasn’t flying. I don’t know how to describe it except to say that perhaps I was still and the world was rushing past me. In moments I was surrounded by darkness. More than that I was hurtling through a kind of vacuum with no body, no sensations. I don’t know how long I continued but I suddenly found myself stopping abruptly at a sort of white wall. It wasn’t a solid wall, but it wasn’t passable either–like a wall of gauze or clouds. I sensed that it was the wall to the world of the dead. Even as I admitted that thought, it seemed preposterous and I began to scratch at it. It fell away like fog in my hands, but however much I tore at it, I didn’t get through and suspected that I would never get through no matter how long I tried.

I began to call out to my mother while I worked. After some time had passed, a figure began to appear on the other side of the wall, just out of reach–not really on the other side of the wall, but coming together from the stuff of the wall itself, recognizable but as flimsy as the ether. It was my mother. I watched her for a long time, then said hello and told her why I’d come. I expected her to smile, but she didn’t.

“Hello, Peter,” she said, finally. “It’s good to see you but you have to stop calling me like this. It’s hard to come together in a shape you can recognize as me.”

“Where are you?” I asked. “What are you doing?”

“It’s not something you could understand. Things are different here. I’m not your mother anymore, but you won’t understand until you get to this place.”

A feeling of abandonment like I’d never known washed over me. “What place? What do you mean you’re not my mother anymore?”

“I’m doing something else now.”

“But what about Tom? Why can’t he see you anymore?”

“Don’t worry about Tom. That was just a dream you had. When it’s time for us to be together we will be, but you needn’t worry about him, or me either. Things are good here. Trust me.” Her voice began to grow heavy, as if talking was a strain. “Just know that I love you and the gang and I always will. But don’t call me. It’s just too difficult and I’m doing something else now. If you really need me I’ll come, but you can’t just call me like this or in your dreams anymore. I love you, kiddo.”

She began to disappear back into the gauze and I was back on the porch, crying, wondering whether I’d really seen what I’d seen. In all the reaches of my imagination, I couldn’t have conceived of her saying what she’d said when she first appeared. But I knew it was crazy to think I’d gone to the world of the dead, if such a place even existed.

I sat on the porch, confused, angry, abandoned, unable to distinguish one reality from the other, the dreams from the visions. And then Julio’s song caught me, and I was a snake. I was not traveling with a snake. I didn’t see a snake. I simply knew I was a snake, or that the snakeness in me had come out for a time. It was fun, sensual. I invited the mosquitoes and other insects to land on me, watched them with flat eyes, then ate them. Mark began to trip up the notched ladder back to the porch, reeling in a spooky windmill motion, his great scarecrow arms and legs nearly disconnected from his body. I had to stop myself from grinning at him like easy prey.

Suddenly everyone was vomiting at once and there was moaning and groaning. It was not good vomiting, it was sick vomiting and I found out later that nearly everyone had ignored my request that they not eat past breakfast. One of the tourists kept saying he couldn’t breathe and was going to die. I tried to calm him down, to breathe with him. Two of us had to carry him back to the small house and sit up with him all night.

The next day I washed in the river early, and though I was weak and still upset from my encounter the night before, I knew I was well. I noted that I couldn’t find any bites from the insects, though I know I felt them all over me. Either I had just been hallucinating them or I ate more than I remembered.

Later that day I returned to Julio’s to thank him. I brought some presents of salt, sugar, batteries and money. He asked if everyone was alright. I assured him they were.

When we returned to Iquitos two days later, Moises was waiting for us at the top of the steep muddy hill that served as the ferry dock. After he got his group settled back in their hotel, he came to my room.

“The old curandera, Maria, asked me to give you these,” he said, handing me a packet of hand-sized, oval leaves wrapped in newspaper. They were datura leaves, used for making toé, a very powerful medicine, one that I knew a little about, but had never used.

“She said to tell you to put one leaf behind your head and one leaf on your forehead just before sleeping. Then crumble a third leaf, make a cigarette and smoke it.”

“What for?”

“She says it will help you dream. You will be able to dream who has stolen your things and where they have hidden them.”

It was a surprising suggestion and one I didn’t give much thought to until I returned to New York some days later to find that my apartment had just been robbed. I called Moises and asked him what else Maria had told him.

“Nothing,” he said. “But why did she give you the leaves for me?”

“I thought you’d asked her for them.”

I told him I hadn’t and he said he’d ask her when next they met. He called me two weeks later.

“She says she was thinking of you one night while using ayahuasca and saw a house in a big city that was in shambles. She thought it must have been yours and that’s why she gave you the leaves. Have you used them yet?”

“No,” I answered. I had thought about using them, but didn’t know what was to be gained. The burglary had happened days earlier and my things had long since been sold. More importantly, the idea of datura frightened me, especially since its use would be unsupervised. It was sometimes the called “the wind that blows you over the edge of the world.”

“But thank Maria for me,” I said. “And tell her the vision was true. Tell her I still have them, in case it happens again.”

Thinking about Maria’s true vision, and unable to forget what my mother had told me, I began to make a mental list of the things I could have imagined my mom telling me if I met her this many years after she died.

No matter what I came up with, I could not imagine that she would have talked about it being difficult to come together in a shape I could recognize as her. It simply wasn’t a thought of mine and it wasn’t a thought I could imagine her having. It wasn’t something I’d seen in a movie or read in a book, and if I’d had endless paper and endless time and wrote down a list of 10,000 things my mother might say on my meeting her after she died, that would not have been on it. When I realized that I realized I knew the difference between a real vision and an hallucination. I had a workable way to think about it, anyway. If something wasn’t on a list of 10,000 possibilities, it was probably a vision.