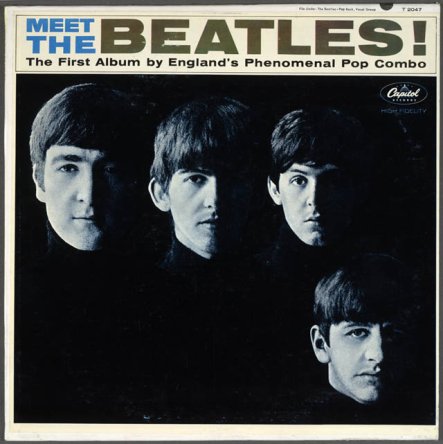

This September, various media announced the release of several new Beatles products — a video game, a complete set of monaural recordings, and a set of albums remastered for stereo. Now, forty years after their last fresh produce, suddenly, they are everywhere. Yesterday, I sat in a bagel shop on First Avenue while speakers played one Beatles tune after another. This morning, in a coffee shop off Union Square, it happened again. (OK, so I live in coffee shops.) It made me wonder if, having announced the last big cultural shift, the Beatles are now announcing the next.

Since last fall, everybody's been talking about the "Great Recession," the economic crisis that Nobel Prize economist Paul Krugman predicted (six years ago) would be "the great unraveling." Many in my community are occupied with the "next age" that they see commencing as we speak. Maybe the Spirit of History, feeling the next great change coming on, cast around for the best available music to announce the birthing, and found that nothing worthy of the gig had been produced in four decades. (But what's forty years in the great cycle of the eons? Nothing. Nothing.)

In his Noise: A Political Economy of Music, economist Jacques Attali argued that when a major social shift is about to happen, it will show up in the music first. He also said that you can tell which particular music is the prophetic vehicle, because people will say, "that's not music, that's noise." When I first read this, it struck me as a bold and far-reaching idea, maybe too far-reaching to have come from a respected social scientist. But having thought about it for a few years, and having considered various possible examples, it strikes me as sort of a no-brainer.

The last really big wave of cultural change commenced in the west on October 17, 1962. I was there. It happened in my living room. There was a local TV show called "People and Places." It was low-budget, bare bones live television at its best, what used to be called a "magazine show." The host, Bill Grundy, announced a group from a neighboring town. They had just landed a recording contract and released a single. The song they sang had been written by their bassist in 1958, when he was sixteen years old. When they had finished their strange number, my mother said, "That's not music, that's noise." Then came the big shift. Now my mother thinks their songs are cheerful and charming. (At one point, she asked me to invite the rhythm guitarist and his second wife over for tea, but we couldn't work it out.) The point is, their music isn't noise anymore, because the world it announced has come.

(Some would point to the so-called "collapse of communism" in 1989-90 as the last big shift, but the Beatles played a role there too. See Leslie Woodhead's documentary film: How the Beatles Rocked the Kremlin.)

Of course, the big shift that we came to think of as "the sixties" didn't suddenly start when the Beatles signed to Parlophone Records. In the 1950s in the US, a big change was building momentum, and again, it can be said to have happened in the music first. The Supreme Court's decision that segregation of public buses is unconstitutional (1957), and the first new Civil Rights legislation since Reconstruction (1958) were prefigured by the at-first-sporadic cross-over of black vocalists into the top of the mainstream pop charts a decade earlier. Maybe the self-declared "brown-eyed handsome man" couldn't live in your neighborhood in ‘55, but he (Chuck Berry) was already in your daughter's room, courtesy of Chess Records.

Elvis and the Beatles may have been the last really big white artists to present black music to white kids who (like me, I must confess) didn't know it was black music. (Amiri Baraka says, "if Elvis is the King, what is James Brown, God?") The success of Motown Records in the ‘60s may have been the breakthrough moment (and that material was deliberately aimed at the white mainstream audience) though it must be noted that it took MTV until the 1990s before a black artist attained a slot in major rotation (Michael, Michael, you are sorely missed).

In 1993, I spoke with Allen Ginsberg about his recollection of early sixties rock. He said that he had been at the Dom, the old Polish community hall in the East Village that was a popular bar at the time. He said that the Beatles came on the jukebox, "I Want to Hold Your Hand," and everybody started dancing. He said his first impression of the music was its unbounded joy. Later, he called rock music "the revenge of Africa." He said it was a return to the body after centuries of living in the head — that the hyperintellectual culture of the capitalist industrial militarist west was finally being taught to shake its ass.

Here we could credit the mind-body split to the birth of modern philosophy, with Descartes in the 17th century, and note that the body crawls back with Sartre in the twentieth. (I mean, if it's all about the brain, then wither Sartrean nausea?) The vogue for French existentialism affected Liverpool in the 50s and 60s, just as it did New York. Beatniks and Beatles shared more than the black turtleneck. But the crucial conjunction was the beat, which is the body.

Musicologically speaking, the Beatles weren't all that revolutionary. In some ways, it was big band music without the band. Then again, in some ways, a single electrified guitar is a sax section if you drive it hard enough. If the arrangement is right, three guitars and a drummer are a big band. If the guy who is wacking out the six saxes with just two hands can sing, so much the better. If three of them can sing in harmony, well, as they say in Liverpool, Bob's your uncle.

The Beatles were the Andrews Sisters backed with a 17-piece band, and it all fit into four guys and one Ford van.

In the 1940s, innovations in microphone technology (driven in part by the rise of radio) fed the trend whereby the competition between big bands came increasingly to depend on the featured singers. (Remember those old movies where four girls or four guys or a small group of mixed voices swing tight, jazz-inflected harmony around one big juicy lollipop of a mike? Deeelicious.) And you could dance to it. That's what's going on here — 1940s jazz harmony, songs modeled on the so-called Great American Songbook of Gershwin and Porter, and a new generation of non-scary white guys in suits bringing you a little spice from the ghetto. Scream.

Word War Two killed the big bands. Among the stranger factors in the bands' demise was that wartime rubber rationing killed off the bus tour — a major vehicle for the propagation of the music. And after the war, thanks in part to cheap GI-Bill mortgages, people moved to the suburbs to sit around the radio rather than go out dancing. Big ballrooms gave way to small bars, and the Mills Brothers swung the black gospel quartet sound with one guitar and a set of drums. Bye bye big bands. (A similar down-sizing happened in classical music. It's no accident that classical composers wrote a whole lot of music for small ensembles in the post-war years. It was the money — orchestras are expensive.) It was also the demise of the dance craze that made swing, brought on in part by the emphasis on radio, records, and the crooners. But the kids couldn't sit still for long — adolescent ants in the pants and the need to dance once again drove the rise of new music. It was, as Ginsberg said, the return to the body.

Some scholar-critics compared the Beatles to J. S. Bach. Snobs may guffaw at this, but it is a fair comparison in some ways. The point is that Bach did not so much innovate as sum up everything that had gone before him. He finished Baroque music. (The end of the Baroque era is generally considered to have come in 1750, the year of his death.) The Beatles, for their part, finished Tin Pan Alley, and they did it in a couple of senses. They produced the last fresh work in the style, and they killed it.

Their early work in particular (and much of McCartney's work throughout, I think) imitated the popular songs of the "golden age" of American songwriting — the commercial pop hits cranked out by Irving Berlin, George Gershwin, Cole Porter, etc., — but they kicked it into a new dimension, where the song itself was no longer the point, the experience initiated by the music was. These songs were vehicles for ecstasy. This was ritual music. It was psychedelic before that term came to be applied to a particular style of rock (of which the Beatles were initiators).

In this sense, the white evangelical Christians who banned rockabilly records as "negroid trash" in the 50s and burned Beatles records in the 60s had it right, the songs did invoke "the devil," which was their name for alternative consciousness, or alternative anything for that matter; in a monoculture, difference in mind, ethnicity, sexuality, etc., is simply wrong. And the Beatles' invocation of something other than ordinary, mainstream consensus consciousness was, in fact, an invocation of ethnic difference, because their music has multiple African connections.

On one level, it is simply that the early Lennon is modeling his songs on Smokey Robinson's, and McCartney is trying to sound like Little Richard. The Beatles were sponges, and they soaked up R&B bigtime. But at a deeper level, it's that in African musics, there is always something else going on: it's never just one rhythm, one tone, one timbre.

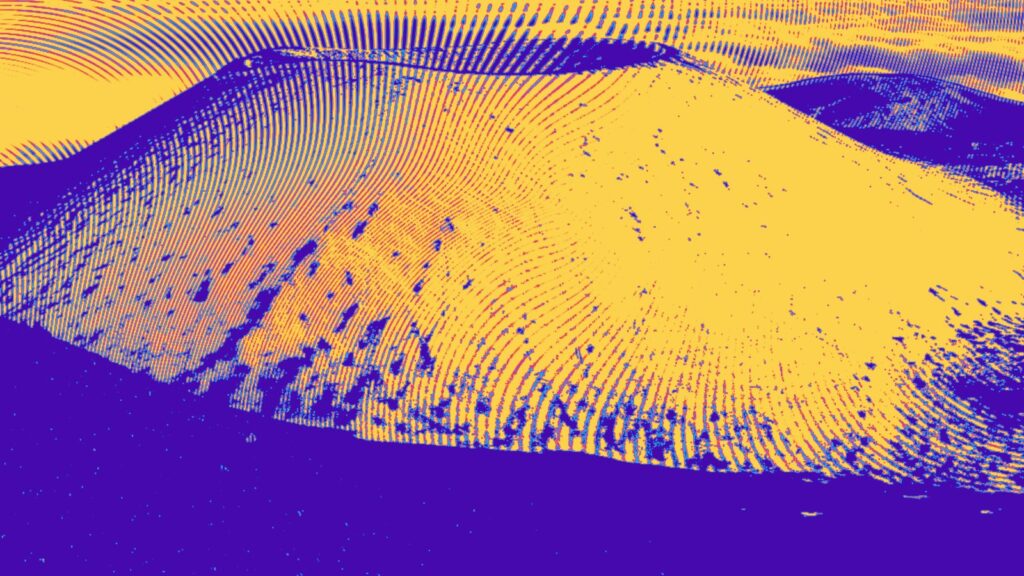

In the west, most pieces of music have a rhythmic base of either two or three. The West African musics that embarked on the middle passage to the Americas, mutated, and then traveled to England via jazz and its progeny, take as a rhythmic base two against three, both two and three at the same time.

Another example of this "something else" can be seen in the instruments themselves. In the west, if an acoustic guitar produces a buzzing or rattling sound, then it has something wrong with it, and it is taken to be repaired so that the buzz no longer happens. By contrast, an African guitar like the tidnit (which is played by the nomads of the western Sahara), has pieces of metal attached to it so that, in addition to the "pure" sound of the string, there is a noticeable buzz and rattle. The overdriven guitar sound that came with the rock of the late '60s is a return to that mutliplicity of tones.

There is another way that this sense of "something else going on" applies to African-influenced musics in the west, and it's crucial to understanding the shift that happened when rock went really big, as well as rock's capacity to drive a change of mind.

Michael Garfield recently reminded me of his notion of "visionary music," about which he has written eloquently on his Evolver music discussion page. In the course of responding to one of his posts, I came to the idea of switching the term from visionary to psychedelic (and applying the latter term more broadly than it was applied in the 60s).

"Psychedelic rock" came about when popular musicians with broad intrests beyond "pop," ranging from folk music to the "classical" and jazz avant-gardes (electronics, chance operations, free jazz), simultaneously discovered first marijuana and then LSD. Although the term is conventionally associated with artists such as Pink Floyd, as Clinton Heylin has pointed out in some detail, Lennon and McCartney were pioneers in psychedelic rock, beginning as far back as 1965 with Dylan's turning them on to marijuana, and with McCartney's research into the technology-driven "new music" fringe of electronic music and tape loops that increasingly fed the Beatles work after '65.

The sense of distance from the conventional mindset, or the objectivity or estrangement with regard to consciousness that comes with chemically-induced psychedelic experience can be seen in the irony that crept into pop music at the same time. The Beatles and other artists may have still been singing romantic love songs, but there was an increasing sense that that wasn't the point at all.

"Psychedelic" (from the Greek psyche, mind, soul, spirit, and d?loun, make visible) conventionally means "marked by or generating hallucinations and distortions of perception," but the etymology would let us apply it to something that makes visible the soul.

According to ethnomusicologist Steven Feld (in his Sound and Sentiment), the Kaluli people of Papua New Guinea believe that the birds of the forest are the souls of their dead. The story goes that there was a little boy who went with his older sister as she gathered food in the forest, and the boy was hungry, and he kept asking his sister over and over for something to eat, but she ignored him. Eventually he died, and as his repetitive complaint changed into a bird song, his body changed into that of a muni bird.

This is an example of music as psychedelic, as something that makes visible the soul, and its agency or triggering mechanism is repetition. As musicologist John Miller Chernoff has noted, his West African informants say that repetition creates depth. A linguist might say that repetition emphasizes the musical aspects of language at the expense of lexical meaning. Perhaps the most notable way in which European and African traditional musics differ is in their use of repetition. In the west, repetition gives way to variation. In Africa, repetition is stricter, and this, I believe, is where the reality shift, ecstasy, or "visionary" comes in.

Let's use the example of two hymns. In the straight Protestant church, the hymn is mostly about the words, it's a vehicle for prayer in the conventional sense of praising or petitioning God. "Abide with me, fast falls the even tide . . ." A whole narrative unfolds, and the music serves the message. In much black gospel music, the words are not more important than the music, at times they become the music, at which point conventional meaning goes unstable. Words and phrases tend to repeat, and ultimately, meaning shifts, becomes strange, or dissolves altogether. It's the difference between "Lord, hear my prayer," and "yes o yes o yes o yes." It's the ecstasy that counts, it's the experience, not the message, or the experience is the message. At a certain level, the words fail to signify, they become music. That's what I mean about the African element in the Beatles music, and the removal of the Tin Pan Alley popular song into another dimension. The song, in a sense, is emptied out in favor of the dance.

You're not going to sit there and ponder the profundity of "Hold me tight, let me go on loving you, tonight, tonight, making love to only you." It's extremely thin poetry, a poor parody of the lyrics of greats like Oscar Hammerstein and Ira Gershwin. But the lyric isn't the point, it's that driving riff in the guitars that makes you jump up and scream, and it just keeps going, even (maddeningly, beautifully) through the middle eight. (That's Lennon's genius right there — on the surface, the song goes extra-sickly-sweet with McCartney crooning about how nice it is to be alone with you, but Lennon just keeps beating the shit out of the Rickenbacker throughout.)

That's what I mean about the Beatles finishing the Tin Pan Alley style. Song, the experience of song, was something different after that. Of course, this was not a new thing, but it was for the majority white audience reached by the Beatles. The great riff-based jazz of bands like the Count Basie group had done the same thing for club audiences in the 1930s. It's the repetition that does it. Repetition makes things strange and deep, and if it swings, it can make you mad with joy. So there's that big band thing again. The Beatles were Basie for honkies. That repeating, driving riff-based music made songs into vehicles for transcendence, not sentimental reflection. Of course, the Beatles wrote ballads too, but that was not where they innovated.

The emergence of African-based styles into the mainstream, or rather the new emphasis on the fundamentals of African-based styles in the mainstream after about 1955, is why Broadway no longer produces new work of value. Music isn't about boy meets girl anymore. That's why Broadway is incredibly lame, year after year. (And the lamer it gets, the more it costs; it's that over.) That's why South Pacific was such a hit last year. All they've got to show for themselves is music that premiered in the pre-rock era, unless it's fake rock. The Who's Tommy, the original album, is about Pete Townshend's right hand and Keith Moon's absolute insanity on the drums. All the other stuff is just window dressing. Four bars into the overture, Tommy on Broadway was dead dead dead, because Pete and Keith were not in the pit. Broadway is actually doing lame parodies of the music that killed it. Saints preserve us. Rock bested Broadway five decades ago. The last great writing talent to come out of the Broadway milieu, Stephen Sondheim, premiered a musical in 1991 called Assassins. The storyline had to do with America's historical line-up of presidential murderers. In the last scene of the show, the assassins all turn to face the audience, and then shoot them. Sondheim, thank gods, finally killed the Broadway audience. Now it's a bunch of zombies from New Jersey.

The Beatles finished Tin Pan Alley in another way. They were not the first mainstream performers who wrote their own material, but they were the biggest, and they set the pattern for the singer songwriter to take over. Elvis relied on a battalion of professional song writers. After the Beatles, the best stuff was written by the people who sang it. I had a teacher in the late 60s who had written songs for the Four Seasons. He sat in an office and wrote songs, but he got no credit. Nowhere will you find his name attached to those hits. He told me that one time he went to his bosses and said he'd like to get credit for his work. They asked him if he'd like to have his legs broken. When the artists — some of them at least, for a certain time at least — took over the business, it's encouraging to imagine that the leg breaking stopped for a time. That precedent is why we now see multitudes of singer songwriters who are also producers and distributors. The Beatles set that up.

So maybe that's the message this time around. Maybe the dying dinosaur of the corporate record business is a sign that now is the time to reinvent music, or is it the other way around? The new music and the new business model it is creating will shift the culture into the next next age. Maybe the new Beatles stereo boxed set will be the last $250 set of recordings ever issued, so that the band will have done one last job of finishing off an old horse. What then, Cassandra? We'll see.