Spoiler alert: Author Peggy Nelson says: "I've received a few comments from people who haven't seen the films yet, and I think they're right, we should let them know that I'm giving some things away!"

Houston, we have a problem. It's outer space again, and the aliens. We think they're trying to make contact. Two films of recent vintage, Moon and District 9, very different on their surface, seem to be carrying the same disturbing message underneath. I think you'd better take a look at this.

Sorry, did I say outer space? Turns out they're a lot closer than that.

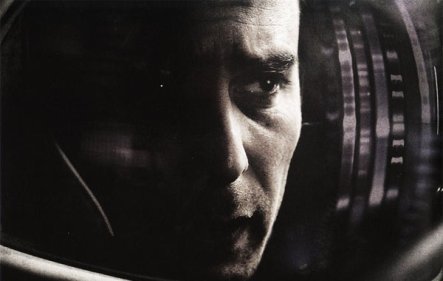

In Moon (dir. Duncan Jones, 2009), a lunar mining base provides helium for an utopian energy grid on earth. Sam Bell (Sam Rockwell), the only occupant of the base, oversees the regular scrapings of lunar rovers, and the just-as-regular transports of rocks. His tour is for three years, after which his replacement will arrive, in efficient military metaphor. There are no aliens; there are no other people. Just Sam, his robot (GERTY), and pre-recorded video from the folks back home. He fills the silence by working out and whittling.

In Moon the look is clean, spare. Interiors are smooth, the moon is empty, and the fonts are appropriately bold. There are a few inconsistent notes in this modernist meditation — a post-it note on the robot, Sam's beard, some disturbing dreams — but overall the look is streamlined and functional, an architecture of reassurance and control.

District 9 (dir. Neill Blomkamp, 2009) is, on the surface of it, a completely different film. Messy, crowded, chaotic, it concerns a giant spaceship hovering over Johannesburg à la Arthur C. Clarke's Childhood's End. But unlike Clarke's endtime emissaries, the occupants of this spaceship are pathetic, injured and confused. When the military finally breaks in (after no signal from the ship for weeks), it finds a neglected refugee camp of insectoid, weakened aliens in the hull, which it wastes no time in transferring to a neglected refugee camp of insectoid, weakened aliens just outside city limits. The aliens probably would have been dispensed with immediately except for their superior weaponry, laser guns that evaporate targets on contact. These have a catch, literally — only aliens can fire them. And only aliens can fly the spaceship, their technology works on a biotech interface right out of the X-Files and Area 51.

Collaged together from shaky handheld camera and faked news video, the look of District 9 is the artless presentation we associate with reality TV – and reality itself. This is control scrambling for reassurance, and not making it.

So far these are not similar at all: no aliens : aliens. Clean : messy. Stylistic : reality TV. Empty : chaotic. Space : no space.

We need to go deeper.

Sam Bell is a clone. He discovers this when the system, literally, breaks down. He revives the previous clone, left for dead in a crash with the rover (generally old clones break down and are disposed of before new ones are revived, in about 3-year cycles). The crash is a manifestation of the degradation inherent in the copying process; with each copy a little more data is lost, a few more errors creep into the system. As memories morphed to hallucinations, Sam1 had started to see his wife and daughter on the lunar surface, which lead directly to the crash.

GERTY is also complicit: it has been programmed, along the lines of Asimov's Laws of Robotics to "Help Sam." In this case helping means eventually revealing to him the truth about his nature as a clone: all Sam's memories have been implanted, like the androids in Blade Runner (dir. Ridley Scott, 1992). There are no live video feeds from his family because — it's not his family. It's the family of the original Sam Bell, who may or may not know about his cloned "spawn."

District 9, meanwhile, has actual aliens, "prawns" in the film's slang, resembling 9-ft cockroaches with tentacles. Upon their removal to earth they've immediately displaced the underclass in a race to the bottom. It's not great, but it's relatively stable. Wikus, a middling bureaucrat at MNU, the multinational agency whose mandate it is to "manage" the aliens, is appointed to head up a field census team. But the census is only a thin cover for another forced relocation, weapons searches, and violence.

While in District 9, the aliens' decrepit shantytown, a vial of mysterious black liquid sprays into Wikus' face. The liquid is a special alien biotech used to interface with the spaceship, and the weapons. But we don't know that yet. Wikus starts mutating into an alien, one appendage at a time.

In both films this is only the beginning. It's not that things are not as they seem, the paranoid narrative that's fueled all Noir, all mysteries, all horror tales — and our political landscape since Watergate. It's that we are not.

Outer space is the great escape, the jumping-off point from the all-too-messy planet, a final divorce of the mind from the body, a rational teleology where everything is clean, logical, and moves at the speed of light, or thought. Kubrick's 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) falls safely within this Cartesian trajectory, where Dave's final apotheosis occurs far out in space, or "far out" in his mind, and is presented as an evolution from earth and the body into the purely mental realm, where physical distances are as nothing, atmospheres are beautiful mirrored nebulae, and there is room for all the Italianate palaces of the imagination one might possibly wish to inhabit.

Italianate palaces are notably absent from Moon and District 9. To wish to evolve away from the body betrays a dangerous ignorance of what the body is. Because what it is, is a mutant: a hodgepodge of cells and information, a nightmare of maintenance and redundancies, an inefficient delicacy in the face of logic, a porous envelope for a magpie's trash; some glittery, some useless, and none having any relation to another except as an accident of proximity. All this is collected together in the scrapbook we call DNA; a language that, despite having only 4 letters, comes trailing etymologies that precede the human.

(And if this reminds you of a certain other Book, cobbled together from multiple, often contradictory sources so ancient as to be untraceable, which we have declared to be a single, infallible entity — you would not be far wrong.)

We can't escape into some dream of perfection, we have to deal. We are always already mutants. This is an idea that carries within it the seeds of its own implementation: to understand is to start to mutate. Sam and Wikus are both exaggerations, the unwilling products of advanced biotechnology — one very planned and project-managed, the other accidental and "wild." Significantly, neither gets anything done alone. Only once they have accepted their essential plurality — Sam in company with Sam2 (the other revived clone), and Wikus in company with the alien cells in his body — do things start to really happen. And the otherness at the heart of the self is only the beginning: the whole thing is open to manipulation, the entire social contract and everyone in it can be rewritten and mashed up, DNA as art material. Because it always already is.

It's not all good. But watching them run, we start to realize that the possibilities for being are much wider for a mutant. Their feats become appropriately cinematic. They break into and out of impenetrable fortresses. They defeat unstoppable enemies equipped with advanced technology. They forge impossible alliances and make them pay off. And they both finally do, in a way, escape.

The superhero is meant to be human, or almost human, but with some larger-than-life capabilities. But what if these capabilities were actually rebranded deficiencies? What if the biotech attachment was actually a prosthetic, needed to partially compensate for some terrible loss? And what if the biotech was at the cellular level – you didn't lose your arm, but you're growing a new one from the inside out. Or an entire new self, with of course greater capabilities than your old self. In the conventional superhero story, this is great! Here, it is — horrifying.

And then it is great.

The mutation spreads, from cells, to self-consciousness, to society. Sam2 stows away on a helium transport; we hear news reports from the trial (for illegal cloning) of the mining company, a mediated soundtrack against a moon-based background of stars. Wikus disappears. We're left with some final clues that he may now be an alien, but with human memories and mind. Meanwhile, the ripple effects percolate through the final credits and the exodus of the audience, unresolved, unpredictable, uncontained.

The films are not cynical about our possible futures among the stars. But both use outer space more as a metaphor for inner exploration, where boldly going requires that those 4 letters be manipulated by more than the correct font. Look deep enough into space, they say, and you'll find the aliens. They will be you.