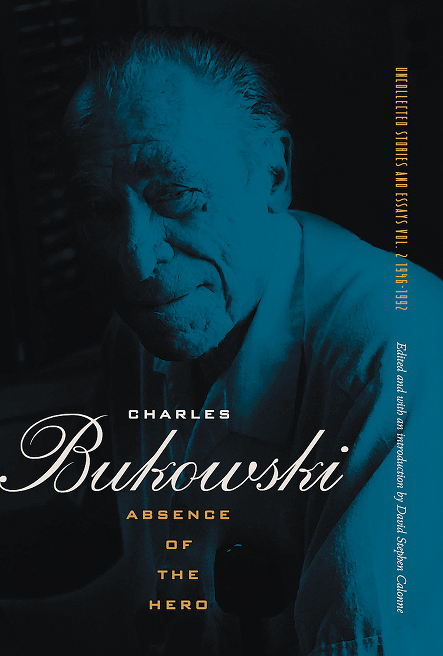

The following is from Absence of the Hero: Uncollected Stories and Essays, Volume 2, 1946-1992, edited by David Stephen Calonne (City Lights).

LA Free Press August 22, 1975:

Down around Sunset, about Sunset and Wilton, near the freeway exit and by the gas station, you'll see them sometimes in their uniforms with swastika. They wear pleasant looks on very white faces and hand out literature. They also wear helmets and some of the boys are big enough to play for the L.A. Rams. They are ready: members of the American Nazi Party. Well, it's Hollywood and one thinks of it more like part of a grade B movie, but then there are those who will tell you that it began that way over there, too — just a few guys standing around who should have been fingering girls in the back seat of the movie house. Next thing you knew they were sitting at the sidewalk cafes of Paris, getting it off. But then if you're going to allow the Communist Party and the Socialist Party and the Gay Party and the Demos and Repubs, you can't very well say, well, the Nazi Party has no right to exist. So there they are but they intend to get the average person more wrought up — memories of ovens and Pathé Newsreels of Hitler screaming, and then they are wearing uniforms that don't exactly remind some of Jack Oakiein bell-bottoms.

Sometimes the police arrive in three or four squad cars. I was gassing up at the station one day when it got very goosey around there. There were seven or eight cops looking very nervous, unsure, grim. The Nazis were gathered in squad formation, standing at attention except for the leader who was speaking to one of the cops. Then back toward Wilton was gathered a group of New York Marxist intellectual types, thin, some Jewish, black-bearded; most were around 5'6", wore old black coats — even in the heat of day — with white wrinkled shirts open at the collar, and they were screaming: "Hey, go back to Glendale, you bastards! Go back to Munich!"

One could sense conflagration, moil, and murder just a tick away. One curious wrong word and they would all be together, upon each other: cops, Marxists, and Nazis.

Sitting there in my car the old thought came back to me: How was it possible for people to believe in such opposite things with such rigor, such energy, such righteousness? How could some people be so sure there was a God and others so sure there was not? How were people unlucky enough to believe in anything? And then if you didn't believe in anything wasn't that a belief? Ta lala.

I got out of my car and walked toward the Nazi leader and the cop he was talking to. The cop saw me approaching first and stopped talking to the Nazi. He watched me. He had red eyebrows and looked as if he were wearing suntan lotion. I stopped three feet away.

"What do you want, buddy?" the cop asked me.

"I want a pamphlet. I want to know what this man's ideology is."

"You can't have one."

"Why not?"

"Because I have given an order to disperse and anybody within this area in five minutes will be under arrest."

"But I'm getting gas."

"That your car at the pump?"

"Yes."

"All right. Fill up and get out."

Cops can kill you and I've been jailed often enough but I can't help getting a sense of the comical out of them. I do suppose that the very fact of their ultimate and unmolested power is what makes them ludicrous. One realizes that power when given even to one man is a very dangerous thing and that man must be of very good soul and mind not to misuse it, and to use it judiciously. Yet in a city like Los Angeles thousands of men are given this power and sent among us with guns, clubs, handcuffs, two-way radios, and high-powered cars; and helicopters, disguises, green-beret training, plus gas, dogs, and even more dangerous: women.

Yet the sense of the comic remains. Once I gave a party at my place and drank too much. I passed out on the rug and the party went on. Then somebody pulled at me and I regained consciousness."Bukowski, somebody's at the door and wants to talk to you." Still stretched on the rug I looked up. It was a policeman with cap tilted rakishly and smoking a cigar. "You own this place, pal?"

"No, officer, but I pay the rent."

"Well, look, pal, I know this place. I've been here before." He inhaled on his cigar and took it out of his mouth and looked at the red and glowing end of it. Then he put it back in his mouth. "I've been here before, pal, and I've got to tell you this: one more call and I'm throwing you in the slammer!"

"All right, officer, I understand…"

Back to the Nazis. I sat in my car and got gassed-up. As I did I saw the leader of the Nazis leave the cop and then stand in front of his troops. Then he gave some commands and they marched off down the street. The New York Marxists followed somewhat behind, still cursing but feeling some minor victory. The whole moil of them turned north up Wilton and I paid for my gas and followed slowly in my car. I couldn't understand what attracted me. I suppose it was only the action, like horses breaking out of the starting gate.

One block up Wilton the troops crossed the street and marched toward a large van. The doors opened in back and the Nazis entered in orderly fashion, sitting down and facing each other, very straight, on long ledges on each side of the van. The doors closed and the leader and one other Nazi got into the front seat. One of the Marxists threw a rock which hit against the rear of the van and fell into the street.

The van full of Nazis moved off. I followed them and behind me were two carloads of Marxists and a police car. I looked back and one of the Marxists hollered at me: "Let's get those sons of bitches!" I nodded and looked forward again. When we reached Franklin I made a sudden right. The disparate fellows continued north. Like fights with women, history never ended. Maybe the balance of everything was the secret: all lawn and no weeds or all weeds and no lawn, and we're really doomed: all spiders, no flies; all lambs, no lions; all me and no you and we were doomed.

I turned south down Western and drove into the liquor store. Two six-packs. All you and no me.