The following is an in-progress essay from the Immanence of Myth anthology. An early version of the Introduction for this project was run on Reality Sandwich in October of 2009.

Now that much has been said about the positive possibilities of myth, it is time that we look at the darker side: not the darkness of evil, but rather of ignorance. When we look out into the world, it is our myths that look back at us. Myths conceal as well as reveal, and the resulting ignorance can be devastating. Clearly, an exploration of this may evoke Weltschmertz in some of you, and an easy reaction to that is to brush it all off as pessimism. I ask you to look past that. Deep uncertainty evokes a terror that is assuaged by belief, but the real enemy is blind certainty.

It should already be clear that the civilization that we live in is the direct result of our ideas and understanding of the universe. Gravity does not work because it obeys Newton's laws, however we used just such theories to get men to the moon and back. Thus we glean the nature of things by extension, extrapolation, and representation, like a cosmologists studying distant galaxies without having ever been there. However, the scientific method and its atomizing focus on the external world has its drawbacks when coupled with an industrial, corporate mythology. The resulting culture neither engenders nor supports spiritual or psychological insight. While we advance exponentially in technological capability, standing, as it has been said, "upon the backs of giants," our spiritual or interior knowledge, in other words our maturity as a race, has yet to advance in any significant and lasting way since the so-called dawn of western civilization.

This is not to say that there have not been amazing advances in the areas of astronomy, mathematics, literacy and education, medicine, and so on. I am casting no aspersions on the scientific method itself, nor the use of reason to derive theoretical natural laws. Science and reason do not, in themselves, determine what end the results are put to.

Many modern myths are based on presuppositions that were ground-breaking in 500 B.C. Certainly, the worldview of the fundamentalist is grounded in such an archaic past. But they are not the only ones. In their day-to-day lives, how many are willing to truly question everything — why do we do things the way we do, why do we think as we do, what are the end results, at what cost? The "common man" of our society wants to get by, get his paycheck, and that means following protocol and playing the game dictated by the unhealthy symbiosis of corporate and consumer culture. Questioning such things is tiring, and if done too loudly, it can get you in trouble. Adolescents are more prone to question the status quo, though they are generally not equipped with the tools to do a whole lot about it. Their rebellion is predictable, and generally toothless, but the underlying motive is valid. Eventually, as they transition into adulthood, the demands of survival require compliance.

It is often only in the few statistical and cultural outliers, most of them misunderstood or even persecuted in their time, that any knowledge outside the fortified walls of cultural orthodoxy carries forward at all. Even amongst these brave and inquisitive, those few who are strangers to their time and place, it can be difficult to wrestle with the weight of several thousand years of invisible cultural history. Finally, there is no clear-cut means of absolutely valuating the answers that we may gather from such questions, though the process of question and answer itself does seem to allow us to gain new insight that can lead to growth outside culturally defined boundaries.

It is our inherited myths that define our way of being in the world, and even when the results they yield are abhorrent we often cling to them to the bitter last. This is not restricted to existential or philosophical issues. Just look at some of the push-button topics of our time: there is little evidence that torture is a useful method of gathering information, solitary confinement has never been proven an effective means of generating reform, and a war on something such as "terror" or "drugs" most likely never be won with bombs, guns, or prison terms. And yet we continue to follow these methods, in the open or in private, because they are a part of our accepted myths.

The basic premises people hold as given, and the realities we each live in, are a direct product of archaic beliefs that are often incongruous with the universe as we currently know it. New myths are framed within the context of the myths of the past, as is demonstrated in the scholastic period of Christianity as the budding mythology of science and reason challenged the beliefs of the time. Those that did not clothe their new methods of thinking in theological terms faced torture or death. Right through the enlightenment, science was framed within a view of divinity first proposed by Aristotle. Only when science was rendered within the framework of religion was it safe. Who can say how the history of science may have otherwise developed. This is just one example of countless legions, and the atrocities that accompany transgressive ideology is not restricted to religious zealots.

Our very nervous systems are dedicated to pattern recognition techniques which serve to make the world around us simpler, so as to build a coherent picture out of chaos. It is arguable to what extent these processes falsify, but it is inarguable that they vastly simplify, distort, or even delete incongruities that don't fit into the schema. Culturally, this functions like a set of blinders; everyone does as they have always done until such a time that something breaks through, at which point the past suddenly becomes alien. The supporters of the singularity hypothesis claim that the rate of progress is speeding up greatly in the past hundred years, possibly putting a great deal of strain on a neurology not yet acclimated to such constant paradigm shifts, but exploration of this is far outside the scope of this survey.

The metaphor of geological stratification seems the easiest way of getting at how myths layer, one atop the other. Ideological histories, or belief structures, build upon each other like layers of sediment. It is never a simple linear progress, each "layer" is composed of a selection of some myths, and yet not others. For example, the initial American government was founded on Masonic ideals, themselves predicated on myths that can be traced back to Rome and Greece, and so on, leapfrogging through time. Our cultural heritage is a palimpsest; the beliefs held in the past continue to effect the world we live in today, regardless of if we see them, or presently believe in them. Cultures and belief systems through time create a mesh-work that contributes inevitably to new forms in coming generations. These cultural underpinnings may co-exist harmoniously, or they may lead to acts of fascism or genocide, depending on the combination of influences and circumstance.

This actually goes beyond metaphor. When speaking of the terms meshworks and hierarchies used throughout 1000 Years of Nonlinear History, Maneul De Landa writes "…we need to employ something along the lines of engineering diagrams to specify them. A concrete example may help clarify this crucial point. When we say (as Marxists used to say) that "class struggle is the motor of history" we are using the word "motor" in a purely metaphorical sense. However, when we say that "a hurricane is a steam motor" we are not simply making a linguistic analogy; rather we are saying that hurricanes embody the same diagram used by engineers to build steam motors — that is we are saying that a hurricane, like a steam engine, contains a reservoir of heat, operates via thermal differences, …" The layers of mythic or ideological accumulation may also operate exactly like geological sediment, including the sorting mechanisms that inhibit or excite the flow of particles, such as mountains and rivers, which block and aid in cultural diffusion.

Due to the invisibility of cultural belief when viewed from the inside, most people act upon this heritage without ever seeing it. The universe we exist in experimentally was formed by Newton, by Kant, by Picasso, and equally by the lives of thousands if not millions of unknown cultural sculptors. In a sense, their ghosts are all still with us. Many of those who contributed the most to the creation of the cultural fabric were simply serving their role within it. Intent is irrelevant in the long-view. After all, it isn't as if Albert Einstein pulled the curtain off the atom so we could turn around and bomb Hiroshima. The river, as I said previously, forever flows downhill; none of us can truly foresee what the next group standing in line will do with our creations, or how our children (real or figurative) will behave once they have left the nest.

The following passage from Jung's autobiography, Memories, Dreams, Reflections is one of the clearest demonstrations of just how complete the "invisibility" of a culture is to those living within it:

"We always require an outside point to stand on, in order to apply the lever of criticism…. How, for example, can we become conscious of national peculiarities if we have never had the opportunity to regard our own nation from outside? Regarding it from outside means regarding it from the standpoint of another nation. To do so, we must acquire sufficient knowledge of the foreign collective psyche, and in the course of the process of assimilation we encounter all these incompatibilities which constitute the national bias and national peculiarity."

When speaking with Ochiaway Biano of the Pueblo Indians, this seems to come together most clearly:

"See," Ochiaway Biano said, "how cruel the whites look. Their lips are thin, their faces furrowed and distorted by folds. Their eyes have a staring expression; they are always seeking something. What are they seeking? The whites always want something; they are always uneasy and restless. We do not know what they want. We do not understand them. We think they are mad."

I asked him why he thought the whites were all mad.

"They say that they think with their heads," he replied.

"Why of course. What do you think with?" I asked him in surprise.

"We think here," he said, indicating his heart.

I fell into long meditation. For the first time in my life, or so it seemed to me, someone had drawn for me a picture of the real white man…. I felt rising within me like a shapeless mist something unknown and yet deeply familiar. And out of this mist, image upon image detached itself: first Roman legions smashing into the cities of Gaul, and the keenly incised features of Julius Caeser, Scipio Africanus, and Pompey. I saw the Roman eagle on the North Sea and on the banks of the White Nile. Then I saw St. Augustine transmitting the Christian creed to the Britons on the tips of Roman lances, and Charlemagne's most glorious forced conversions of the heathens; then the pillaging and murdering bands of the Crusading armies…. What we from our point of view call colonization, etc., has another face — the face of a bird of prey seeking with cruel intentness for distant quarry — a face worthy of a race of pirates and highwaymen.

Though I don't want to stray too far off course, there is a striking passage I would like to share from Noam Chomsky's essay After Pinkville that further demonstrates the scope of cultural subjectivity, even, or perhaps especially, in the face of genocide.

"Some time ago, I read with a slight shock the statement by Eqbal Ahmad that 'America has institutionalized even its genocide,' referring to the fact that the extermination of the Indians 'has become the object of public entertainment and children's games.' Shortly after, I was thumbing through my daughter's fourth-grade social science reader. The protagonist, Robert, is told the story of the extermination of the Pequot tribe by Captain John Mason: His little army attacked in the morning before it was light and took the Pequot by surprise. The soldiers broke down the stockade with their axes, rushed inside, and set fire to the wigwams. They killed nearly all the braves, squaws, and children, and burned their corn and other food. There were no Pequot left to make trouble. 'I wish I were a man and had been there,' thought Robert.'"

These two passages show two very different cultural biases. Clearly, each culture has its own, and within each culture, there are divisions and sub-divisions down to the view of each individual. This is the very kind of cultural relativism that so many academics desperately want to dismiss, for it implies a groundless chaos, but with the revisions of the word "relativism" to "contextualism," I think it most clearly demonstrates the way our world works, horrifying or no.

This is not said to posit a stance that genocide is a strictly "white" phenomenon. Far from it. "Rebelling Indians in Peru and African slaves in Haiti, for instance, committed genocidal massacres of European settlers and planters. Elsewhere mass killing occurred in the absence of colonialism" (Kiernan, Blood and Soil). These examples just pose some of the most stark examples of the extreme power of cultural bias.

The development of technology also follows the course of myth. The concept almost always moves a step ahead of actualization, so it was only after the myth of the atom was born that we could develop technologies that harnessed its power. Underlying the technological history of the western world is the ever-present myth of progress, which found its crystallization in the Enlightenment that reformed the 18th and 19th centuries. This myth presupposes that time moves in a straight line, a teleology with man at its center, approaching god-hood by half-steps through the divine providence of reason.

However, this myth did not end there. As the industrial revolution progressed, this myth was reformed in the likeness of industry, rather than divinity. This had far-reaching repercussions. Our public education system was fashioned after the machinations of the factory, a regimented process developed to create good workers to tend the machine, sent from task to task by the ring of an alarm bell. Increasing populations and a cultural emphasis on quantity rather than quality structured, and continues to structure our grading system. Our technology, too, focused on the utility of the consumer market that supported it.

To put it bluntly, much of our technology is ecologically and spiritually stupid. In recent years this statement has become self-evident: an increasing majority of the scientific community now agrees that our very way of life is unsustainable without serious modification. Western culture — certainly American culture — has dedicated its effort almost exclusively toward industry and the worship of God money. As a result, the technology we have developed has been smart in the terms defined by the corporate / consumer mode of thinking, but not in any other way. For example, designed obsolescence makes perfect sense from a consumer and manufacturing standpoint: it keeps people buying new units, and with the rate of technological advance, most of us want to buy a new laptop every couple years, so we don't mind so long as the technology is relatively affordable. However, it also means committing non-renewable, often highly toxic material resources to be transformed into short-lived devices that wind up in a landfill. An even more clear example of this came about when corporations realized they could sell us bottled water: packaged in plastic, oftentimes shipped halfway across the world, and bought at nearly the price of fruit juice. Our culture simply doesn't support the consideration of value outside the economic matrix of desire and fulfillment.

None of this is to say that there is anything inherently wrong about corporations or industry. However, when they become the sole indicators of cultural and personal value, there are considerable repercussions. Rather than being a system that we use, it becomes a system that uses us.

Let's consider another example. It is hard to imagine that just seventy years ago, there was no real military industry in the United States. The second great industrial boom in America came on the heels of World War 2. The war was one of the factors that brought about the industrial demand necessary to pull us out of the depression of the 1930s. The department of defense now takes up more than half of the federal budget. In 1961, President (and former General) Eisenhower gave a speech about the military industrial complex that has an almost prophetic air to it. I think the following extensive quote sheds light not only on this particular issue, but much of what has been discussed in this section:

"This conjunction of an immense military establishment and a large arms industry is new in the American experience. The total influence — economic, political, even spiritual — is felt in every city, every State house, every office of the Federal government. We recognize the imperative need for this development. Yet we must not fail to comprehend its grave implications. Our toil, resources and livelihood are all involved; so is the very structure of our society. In the councils of government, we must guard against the acquisition of unwarranted influence, whether sought or unsought, by the military industrial complex. The potential for the disastrous rise of misplaced power exists and will persist. We must never let the weight of this combination endanger our liberties or democratic processes. We should take nothing for granted. Only an alert and knowledgeable citizenry can compel the proper meshing of the huge industrial and military machinery of defense with our peaceful methods and goals, so that security and liberty may prosper together."

Akin to, and largely responsible for the sweeping changes in our industrial-military posture, has been the technological revolution during recent decades. In this revolution, research has become central; it also becomes more formalized, complex, and costly. A steadily increasing share is conducted for, by, or at the direction of, the Federal government.

Today, the solitary inventor, tinkering in his shop, has been overshadowed by task forces of scientists in laboratories and testing fields. In the same fashion, the free university, historically the fountainhead of free ideas and scientific discovery, has experienced a revolution in the conduct of research. Partly because of the huge costs involved, a government contract becomes virtually a substitute for intellectual curiosity. For every old blackboard there are now hundreds of new electronic computers.

The prospect of domination of the nation's scholars by Federal employment, project allocations, and the power of money is ever present and is gravely to be regarded. Yet, in holding scientific research and discovery in respect, as we should, we must also be alert to the equal and opposite danger that public policy could itself become the captive of a scientific technological elite.

It is the task of statesmanship to mold, to balance, and to integrate these and other forces, new and old, within the principles of our democratic system — ever aiming toward the supreme goals of our free society.

Another factor in maintaining balance involves the element of time. As we peer into society's future, we — you and I, and our government — must avoid the impulse to live only for today, plundering, for our own ease and convenience, the precious resources of tomorrow. We cannot mortgage the material assets of our grandchildren without risking the loss also of their political and spiritual heritage. We want democracy to survive for all generations to come, not to become the insolvent phantom of tomorrow.

Yet this is precisely what has happened. In the time since, the financial demands of this military industrial complex have required the invention of wars-without-end based on what is a faulty concept, even in an economic sense. (Wars may help failing economies recover, at least in the Keynesian model, but they are a drag on healthy economies.) I am not making this point to political ends. This is just another instance of how each point in history draws on its past: now we must contend with this complex, and it makes its demands upon us, rather than the other way around.

The corporate / consumer system carries us forward to an inevitable end, and that end is the end of history, the end of its own desire, its own motivation. The motivating factor behind our growth to the furthest reaches of our planet, even to outer space, is nothing other than the urge to compete, destroy or multiply.

We like to frame our Promethian jaunt to the moon as a journey motivated purely by scientific curiosity, but it was surely more motivated by our ongoing race with the Russians. After the cold war, we see no such concerted drives, and our space program languishes under the weight of bureaucracy and poor funding. I am also using this purely as an example, I'm sure you can think of many others.

These are the motivations of man as animal: health, wealth, progeny, conquest, and so on. In fact, all of the basic animals drives, which essentially power civilization as gasoline powers a car, is libido. Despite the fact that the term, in common parlance, has been reduced strictly to sexual energy, that doesn't tell the entire story. Carl Jung helped explore this in Wandlugen und Symbole, which he paraphrases on pg. 208 in Memories, Dreams, Reflections,

My idea was to escape from the then prevailing concretism of the libido theory- in other words, I wished no longer to speak of the instincts of hunger, aggression, and sex, but to regard all these phenomena as expressions of psychic energy. In physics, too, we speak of energy and its various manifestations, such as electricity, light, heat, etc. The situation in psychology is precisely the same.

What is of note, then, is not that libido is the fuel powering the machine, but rather the direction that the driver seems to be taking us in. The corporate / consumer paradigm is yielding poisons rather than elixirs: disease, vastly unequal distributions of wealth, and a looming population crisis. Most curiously, they are being carried out as if they willed their own annihilation. This paradigm is our suicide machine. Though Ray Kurzweil's predictions in his book The Singularity Is Near about the exponential growth of processing power seems correct, it seems he forgot to realize that such "progress" bears no necessary relation to our own internal evolution. A tool is only an extension of its maker. Modern man is an ape with a rocket launcher.

This brings us to another facet of our predicament. For most of us, the bulk of the technology which we receive in the private sector may as well be magic devices. Without the relative few who truly understand the principles used in the manufacture and upkeep of these devices we would be plunged back into the technological dark ages. I am not proposing this as some sort of doomsday scenario, but it says something about our cultural role as consumers. Most of us are no longer equipped to deal with the harsh realities that such a dark age would entail. This makes nearly all of us – including myself – dependents upon the system, domesticated animals without any capacity to thrive or even survive on our own without accepting our role as the cog in a cultural machine which is primarily beneficial to those who build and propagate this machine, such as it is.

We may feel a kind of Stockholm Syndrome, and many of us are certainly afforded many comforts, even luxuries, as a result of our place within this system, but we are nevertheless to one degree or another complicit in the results that this machine renders. Any successful cultural solution to this problem must take this to heart, as all "escape to the forest," Luddite communes are doomed to failure from the inception in a cultural sense, when founded on an idealized concept of survival truly "off the grid." Thoreau could have been correct when he said "most of the luxuries and many of the so-called comforts of life are not only not indispensable, but positive hindrances to the elevation of mankind." However, it is unlikely that the future of mankind will be lived out in log cabins, and a mass-culture of isolationists seems improbable to say the least. Despite the fact that teleological progress is a myth, it is impossible to move backwards. We are all connected, and we cannot undo what has been done, only take action in the present.

This "suicide machine" is the ultimate result of ideological forces, carrying themselves out through the theater of history. In a historic sense, America is moments past its industrial boom, with countries like China and India rushing even more quickly through theirs, with just as little attention paid to the ultimate results of such blind progress. (It is especially interesting to me that India and China in particular are going through this process. Though the "cultural revolution" in China did distance them from their past in some ways, both have an ideological history that is on the whole much richer in psychological and spiritual insight. Nevertheless, the demands of developing in an industrial sense seems to require turning a blind eye towards that. Where their industrial revolutions will lead them is anyone's guess.)

We will very soon reach a crisis point wherein these technological and cultural ignitions will either lead to paradigm shifting technologies and a new way of being in the world for all of us, or nature will force that change upon us — the latter route being, most likely, on the heels of a die-out event unlike any we have seen, at least since the bubonic plague. That's where we are in "interesting times," as the famous Chinese curse refers to.

None of this is to say that the society we live in is the direct result of conscious planning on the part of a government, or some secret Illuminati or Masonic order. Though there are surely sociopaths at the helm of many major corporations, this "suicide machine" does not require any conscious malice to run its course. Even the best intentions, when rendered within the framework of this system, will yield the same results so long as you follow its definition of success and progress. The machine is simply the result of unchecked ideological forces.

We will be providing possible solutions to this, by way of new possibilities for the interpretation and creation of myths, in the full anthology. Visit here if you would like to contribute.

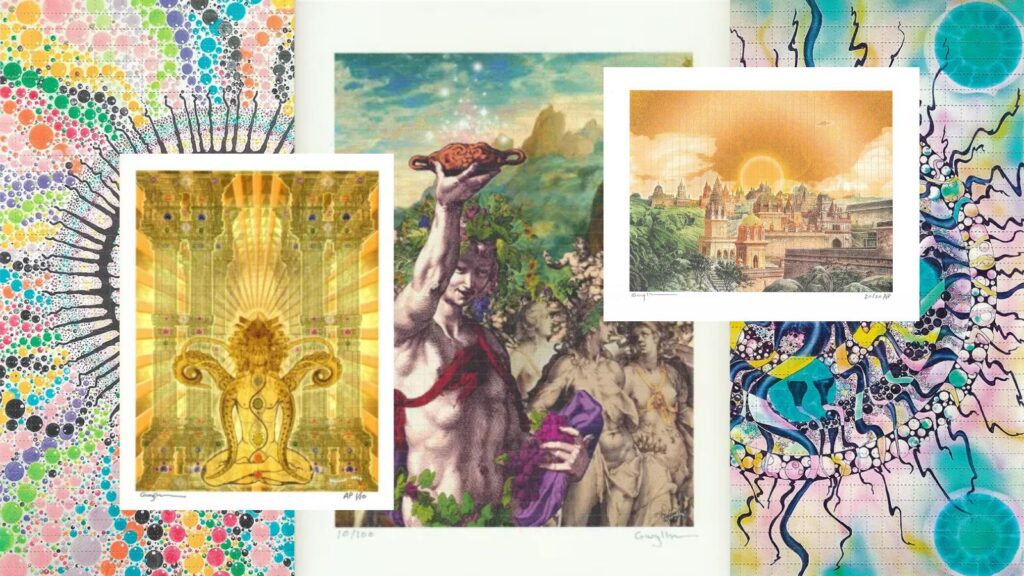

Image by .sandhu, courtesy of Creative Commons license.