I keep having this nagging

notion that all life is sacred. That means animals and

plants. And that Life depends on Life to exist, however hard that is to accept.

So with years spent vacillating between vegetarianism and veganism, often

feeling justified in my moral uprightness by not eating meat, this concept

reduces my "rightness" to rubble.

Disclaimer: I respect all

omnivorous, post-modern dietary choices. Meat-eater, vegetarian, vegan,

raw-vegan, paleolithic, whatever! But lately this poking, tug-at-my-sleeve

thought prevails every time I eat a meal: all

life is sacred.

Then I begin to see that

eating a piece of beef and eating a head of lettuce are both the consumption of

Life. If the life being taken has been honored, cared for, given proper

respect, then the act of eating becomes about unity and connection to other

life forms, which is the underlying truth of existence on this planet. And for

that matter, the act of eating also becomes a direct relationship to death.

Plants, seeds, birds, all must die in order for me to live. Or using different

language: energy must be recycled that I may live. Energy can neither be created nor

destroyed, they said blandly in high

school science. I understand that to mean all energy; the energy of a beating

heart, of respirating breath, even the energy of cell division.

With that in mind, a meal

takes on deeper meaning. So that taking the life of a turkey to celebrate

family and community and give thanks on a holiday begins to seem somewhat

appropriate. Especially if that turkey lived fairly, cared for and raised in

the neighbor's yard and I am taking responsibility for its death at my table.

Indeed my own mortality is tied up with that turkey's mortality.

Death used to be

acknowledged in the very essence of daily life for humans. From our earliest,

more tentative existence to the death practices of our recent ancestors. Tending

the body in the kitchen, showing it in the parlor, digging the dirt, placing

the gone-flesh in the ground. Now we have very little to do with death, fear it

to the extent of subtle mania, expose such in our over-zealous cleanliness and

insistence on letting others do the work for us. How did my grandfather get

from the hospital bed to that casket? How did my turnips get on that grocery

store shelf?

(By the way, insects and

weeds must die for us to have fresh produce. I remind myself of this crawling

through the garden pulling up dandelion and chicory, squishing stink bugs off

the squash leaves.)

The problem with being at

the top of the food chain, and having the frontal cortex that allows

analyzation and self-consciousness, is that we are cursed with knowing what it is that we do. I know that bug will never fly again into the

cool night. You know you take a beautiful summery day or the acrid smell of

rain on hot earth away from that chicken. Does the chicken know? Does it

matter? We know. But the great gift of being human, of having that frontal

lobe, is the same as its curse: self-consciousness! Being present for every

moment of excitement, expectation, sorrow, anger, fear, and gratitude. All

emotions of daily life. All emotions involved in the reaping and preparing of

animals, birds, fish or plants for daily nourishment. This is the emotional

framework of the life/death cycle.

Whereas once upon a time we

were present with and mandatorily (by nature of the exchange) took

responsibility for taking life that sustains our own, now we can walk in a

grocery store and buy lamb chops cleaned and tidied in clear plastic wrap, or

reach for a sealed bag of spinach with perfectly formed leaves minus bug holes.

Perhaps the omnivore's dilemma is the same as the dilemma of contemporary

society; that is a seeking of connection to the nourishment that sustains our

life. Of seeking connection, God, community, all things that are just different

names for the same thing.

As I write this I still

have not eaten meat exactly. I did resume eating eggs (local pasture raised)

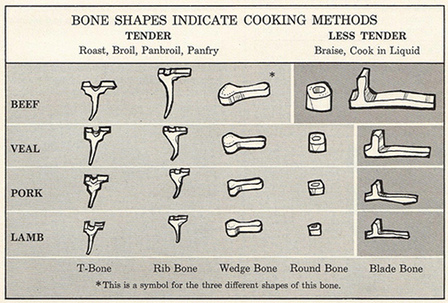

and brewing my own bone broth. Bone broth, as I have come to understand, is

full of easily absorbed essential minerals, glucosamine, and gelatin. I can

attest that my body has responded kindly to this new nourishment. As a matter

of fact I have fallen into a new weekly rhythm around my broth. I walk to the

local butchery a few blocks away, where the woman butcher and her employees all

know me and greet me when I come in. Every week I ask questions and they offer

answers, we laugh, talk about the upcoming local goings-on while I pick up my

poultry bones and a dozen farm eggs. My butcher believes in working with local

farmers and clean, properly-fostered meats. This makes me trust her. They find

me somewhat amusing, the new lady who only buys bones and eggs, who is too

timid yet to buy a whole bird to cook, eating the meat and utilizing the bones;

but we get along. I then walk home and brew the bones in a pot for six plus

hours. I spend those hours at home with the soft smell of food wafting through

my house as I clean or read or tend to phone calls with friends. On Sunday I

make a soup with the broth that when I taste it, has such a richness and depth

that my whole being feels nourished…from the friendliness at the butchery, to

the time spent preparing my food, to the sitting down and offering it to my

body. And every week I take a big bowl to my mother. All this from a simple

bone broth.

I still tend to find the

vegan option on the menu when dining out (unless it's an organic establishment)

because I lack trust in the typical sources of fish, meat, and eggs; and for

energetic and health reasons I choose not to put industrial-produced animal

products in my body. Though by now my undeniable hankering to take full

responsibility for my place in the food chain has proved worthwhile. I find to

do this authentically, I must acknowledge death in each bite as intimately as I

acknowledge the life. Still curiously surprised by where this strange notion — All life is sacred — is taking me; I go willingly. And giving proper

thanks.

Image by Thoth, God of Knowledge, courtesy of Creative Commons license.