After first reading Douglas Rushkoff's work here on Reality Sandwich, I decided to give his comic book series, Testament, a try. I highly recommend everyone go out and do the same.

Testament is a well-crafted, highly intelligent weaving of hopeful, contemporary grit and progressive Biblical story-telling.

Douglas retells Bible stories with a scholarly eye for the true complexity of their accurate cultural and historical context. While doing this, he hypertextually links the ancient influence of these story lines – their timeless archetypes – into a picture of reality that is neither distant nor imagined, though alarming in its implications.

Testament is unlike any graphic novel, comic book, or spiritual literature I've ever read, and so it's difficult for me to place it into a genre. How do you describe Testament?

Well, I'm hoping it's actually closest to classic spiritual literature in its form and intention. The original hearers of Torah didn't consider the text to be a historical document – even though these audiences were separated by many centuries from the narrative being described. That's because, in addition to telling the classical myths, the Torah and other classical texts had many winks and nods to the contemporary audience. Puns that only made sense to contemporaries, or analogies that had much more to do with contemporary politics than the "original" story being told.

The Passover Haggadah – the little book of the story of Moses that Jews read on Passover – is actually an allegory for the Bar Kochba rebellion against the Romans, shortly after Jesus's time. The book was being read aloud around the dinner table by people who were engaged in an active rebellion against the Romans. So that's basically the formula I use in Testament, except instead of using Torah stories to comment on Roman fascism, I'm using it to comment on corporate fascism.

The other big point of the book is to use the panels – the form of comics – in order to tell the story in a way that just couldn't be done in any other medium. Deep down, I'm media theorist. So I have a strong need to see media being used for their own particular strengths, rather than simply as test runs or sample scripts for more lucrative ones (like movies or an HBO series). Comics are unique in their relationship of text to image, and panel to panel.

What I've been thinking about since Scott McCloud wrote about the relationship of image to "gutter" – the space between the images – is what would happen if there were characters who lived exclusively in the gutter of the pages? And the gods of Testament turned out to be perfect characters for this.

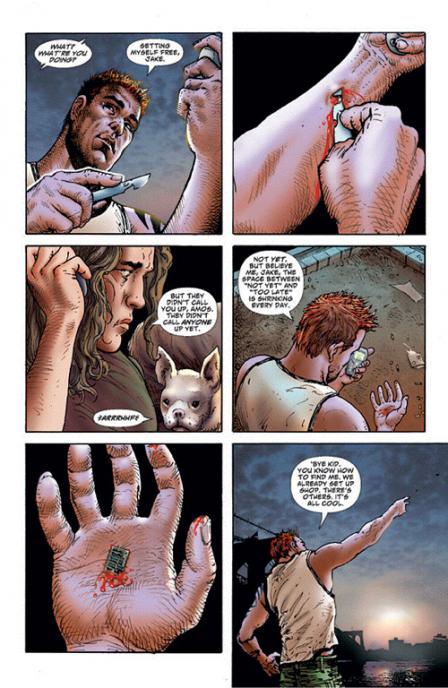

The sequential action of the comic takes place in the panels, like any ordinary comic. But the timeless action – the action occurring in the realm of the gods – takes place in the gutters between the panels. The gods can't even enter the panels, the realm of humans. If they push their hand into a panel, it transforms into something else as it passes the panel border. So Moloch's hand becomes fire, and so on.

It kind of explains the burning bush and other phenomenon in Torah where a god is attempting to speak directly with a person.

Describe the evolution of your work. How was Testament concieved and where did you find inspiration for the project?

I guess it was conceived in my head. I had a sudden opportunity to pitch some comics ideas to Jon Vankin at Vertigo. And I knew they wouldn't take this one, but I figured it'd be a fun thing to pitch. It started as just Bible stories, told raw and real they way they are in the Bible. I mean, most people don't know that Lot had sex with his daughters, and this is the line that pretty much every super-holy king ends up coming from. And most people don't get just how contemporary and relevant these myths are. They tell the story of how we got enslaved, not just by some Pharaoh but by a centralized monetary system, false scarcity – all the kinds of stuff people write about here on Reality Sandwich, actually.

The Bible tells the story of how a faulty model can get mistaken for reality, and how that can slowly rob us of our humanity. And given that we still sacrifice our children to false gods (oil), still worship idols (the dollar), and still enslave one another for financial gain ("developing" nations), it seems these myths are not only relevant, but living.

Then Jonathan thought I should make the modern aspect of these stories more specific, and so I developed a modern story of a group of contemporary, counter-culture, cyber-alchemist Burning Man type kids from Brooklyn who choose to rage against the machine they're supposed to become a part of. It's the near future, and everyone is supposed to be implanted with an RFID tag so they can be tracked for the military draft and, more importantly, their consumer behaviors. There's a big war in the Gulf, and the Bible stories seem to be repeating themselves.

So our characters end up playing their own roles in "real" life, and then serving as the cast for the Biblical stories that echo the same dynamics. Eventually, the characters wake up to the fact that they're living on more than one timeline, and that the stories in which they're trapped are not totally of their own making. The final revolution needs to be against the gods, and the story, themselves.

The story lines of Testament have a real urgency to them, but this is tempered by a sense of archetypal timelessness. What do you consider "the story" of Testament to be? Was there a sense of urgency for you as you wrote the series?

The sense of urgency is really the rapidity with which global corporate fascism is taking hold. No sooner do I dream up an outlandish possibility (workers being fired for not accepting RFID implants) than they happen.

For me, the urgency is helping people wake up before they surrender totally to the slave mentality that the Bible warns us against. These are really easy times to surrender to a myth – to see it as real. That's how most people are using the Bible, which is really ironic: the thing was written to help people break free of myths. God, in many ways, is the bad guy. But people got it all turned around.

I'm not satanic, don't get me wrong, but I read the Bible by actually looking at the words on the page and then researching the experiences and cultures of the people for whom the Bible was written. And then you get a very different picture of what these stories were meant to do than if you just listen to a televangelist say you're going to hell.

The urgency is to see what a totalized global economic empire does to consciousness and behavior. How much violence and destruction is required to maintain it? What leads to the least child sacrifice?

You present some pretty amazing Biblical scholarship. Have you met with any resistance from scholars in the Christian community? In what way is Testament a commentary on contemporary Biblical scholarship?

I tend to get more resistance from certain camps within the Jewish community. Christian scholars, like Jesuits in particular, play their scholarship a bit more fast and loose. They're more into the multi-disciplinary approach to literature. And they have less at stake in the "Old Testament" being true than do certain of today's Jews, who are still using the Torah as proof of a land claim, or of the legitimacy of the Testament.

Honestly, though, most trained Jewish and Christian scholars really enjoy the book and its riskier interpretations. Right in the first issue, I suggest that it's the Canaanite god Moloch (and not Hashem or the main Bible god) who instructs Abraham to kill Isaac. Now the actual Torah doesn't quite say this, but if I say so myself, it's a fascinating possibility. Even conservative scholars would agree that what makes Abraham unique is that, unlike the others around him, he decides not to sacrifice his son. (It's what people did to appease the gods, after all.) This was the beginning of Judaism: a new religion, dedicated to a new, kinder god who did not require child sacrifice.

So why not have the command to Abraham to kill his son come from one god, and then the countermand come from a different god? It makes the shift from one set of gods to another much more explicit.

And then (this is the scholarship part) if you look back to the Torah text, you begin to see all sorts of hints that it really was Moloch who told Abraham to kill Isaac. But you don't get to have any of this really deep, James-Joyce-Finnegan's-Wake-like experience of Biblical literature unless you don't need it to be historically true.

So the answer is, yes – there's been a little bit of upset, but not nearly as much as when I wrote a much simpler book (Nothing Sacred: The Truth About Judaism) explaining how all this works, and not nearly as much as all the positive speculation and discussion that's been prompted in the more liberal Biblical scholarship circles.

You mention that the Bible might be understood as an "open source" collaboration in the intro to the series. Could you explain this?

Well, unless you need to believe that the Bible was really handed down to the character Moses on Mt Sinai, you are free to engage with the overwhelming evidence that these stories were developed over centuries by many different cultures, and slowly amalgamated into the text we now call the Bible. And the process took centuries, and was the work of a kind of debating society of scholars and scribes.

The books were put in, taken out, changed, added to. There were real negotiations – which is why sometimes both endings of a contested story end up appearing. Hell, there's actually two contradictory creation stories in Genesis, just a page part. (I end up telling both in Testament – one as a "rewrite" by the gods who don't like how the first one turns out.)

More significantly, Jewish law really was an open source proposition. It was written and amended, each new generation interpreting and changing the law as they saw fit. And certain aspects of the "kernel" were agreed upon, others left for future discussion. So the hypertext, always-edited Talmud really is an open source effort.

Do you see the potential for a hypertextual collection of religious scriptures and stories from around the world? What would have to happen to make this kind of project happen?

It'd be hard, since the people who generally have enough knowledge and dedication to make something like this happen are also the people who are committed, in particular, to a certain faith. Most of these really committed folks don't like to find out how similar their beliefs are to someone else's. (You should see how upset Jews and Christians alike get when they find out how many other religions have flood mythology, but with heros other than Noah, and entirely less particularist outcomes. Or when they find out that the Genesis creation story was added way late to the Bible, and cobbled together from a bunch of other people's myths.)

I myself own the domain name for "open source religion" – though I wasn't invited to the Open Source Religion conference, which means maybe I should give it up to someone who was! I tried to start something called Open Source Judaism, and got as far as a Haggadah that lets people add their own interpretations, select from those by others, and print out their own final version. In the end, there wasn't enough interest or money around to fund it.

There's another site out there called RitualWell that puts together rituals from a number of different religions. But the giant, editable, hypertext mythological compendium will probably have to wait until this stuff is easier and cheaper to program. Wikipedia can't even pay its bills in the current climate.

What has the creative, collaborative process for Testament been like – working with illustrators, for example? Do you find collaboration more difficult than creating art independently?

It's really only more difficult because the artist is in the UK. I've never met him, and the D.C. process is one that's extremely writer-driven. There's been so little time that we don't get to discuss much. He gets a script, draws the pictures, and then I have to change my script to match them. Some characters ended up looking so very different from how I conceived them that I ended up writing entire storylines just to get the characters switched around and responsible for the actions that they'd have to be taking later in the story.

[Testament artist, Liam Sharp] is a tremendously talented guy, with a really complete vision of how things can be. We really owed it to each other, and to the series, to have a few beers or joints and spend a month together before the mad rush to meet the monthly schedule began. That may work for oversimplified superhero books, but it's really hard when you're telling this much story at the same time.

So yeah, it was really difficult. For the next series, I've already been working live and up close with the artist. And that really helps. Plus it's going to be a simpler book.

Who have some of your influences been? Did you ever feel these folks entering into the world of Testament?

Jack Kirby, for sure. I wanted to do Eternals, but that's Marvel and the people interested in working with me were D.C. Grant Morrison is a good friend, and he's influenced me more through his personality and approach to writing than his actual comics. It's hard to explain – you'd have to meet him. He exudes something.

My editor, Jon Vankin, taught me how comics work – quite literally. Scott McCloud, for sure. Jeff Newelt aka JahFurry has consistently demonstrated that comics generate a community of "love" in a way that regular literature never has. All the guys at Act-i-vate, like Dan Goldman and Dean Haspiel, have taught me about the way artists work, and made me a better writing partner for Liam.

As far as more intangible influences, I'd have to say Jonathan Lethem, Samuel Beckett, James Joyce, Richard Metzger, Genesis P-Orridge, William Burroughs, Paddy Chayevsky. Sometimes their names pop up on my pages in special little places.

The next issue comes out later this month. (I have my copy pre-ordered from Amazon.) What should we expect?

The third collection is available now, and the final collection will be out next spring. There will be 22 issues in all – at least of this particular incarnation of the series. But the collections are where you get the footnotes to the whole series (there, or online) and those really do help make the experience richer for a lot of people. I keep saying that there's no need to know anything about the Bible to enjoy it. In some ways, not knowing the Bible makes it easier. But people are really interested these days in original sources, so the notes help people find the chapter and verse or the historical reference I'm making.

As for what to expect, you should expect Exodus. The release from bondage. The last issue will be called "Full Bleed," so if you know anything about printing, that should be a dead giveaway about what happens to the realm of the gods.

What do you see coming after Testament? Do you have any visions for future work? How about a comic-book Bible!

I'd love to do the entire Bible as a comic book, fully annotated. Not all preachy and devout, but rich, historical, and highly Midrashic (interpretive). It's too early to put the Bible to bed.

But what I'm doing next is a book (a regular, printed book with words) on corporatism. I'm looking at how we have internalized corporate values. I no longer see "corporations" as the enemies we need to attack. Rather, we need to look at how to build another society that uses different organizing principles than the ones created in order to keep corporations and other central authorities in power. It's a really easy concept, but unraveling the obstacles to seeing it will take some real work on my part. Right now the book is called Corporatized: The Myth of Self Interest, but I have a feeling that title might change.

I'm also starting on another comic book, but it isn't announced yet. And I'm more fully committing to my column in Arthur magazine, which I hope will become a sustaining piece of work rather than a pure labor of love. Finally, I'm working on a dissertation about the biases of media that I plan to publish as a book (in a simpler form) after that. In some ways, that one looks like the most fun to me, because I get to tell the whole truth without any concern for whether people feel like spending centralized currency for it.