You will think, perhaps, that I am too confidential and communicative of

my own private history. It may be so. The fact is, I place myself at a distance

of fifteen or twenty years ahead of this time, and suppose myself writing to

those who will be interested about me hereafter; and wishing to have some

record of a time, the entire history of which no one can know but myself, I do

it as fully as I am able with the efforts I am now capable of making. —

Thomas De Quincey: Confessions of an

English Opium Eater (1822).

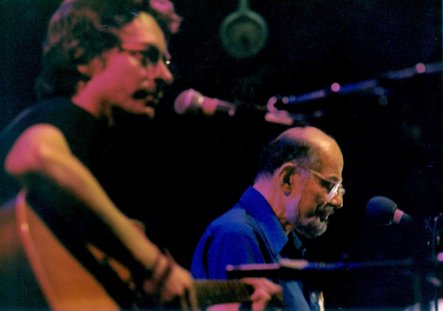

In the spring of 1976, I chanced to sit in as accompanist with Allen

Ginsberg at a poetry performance. We went on to live, work, and travel together

periodically until his death in 1997. A couple of years ago, as I was finishing

a book accounting my travels on the anarcho-punk scene, I began making notes

toward a memoir of Ginsberg and his milieu.

The project really goes back to our

first meetings, when Allen urged me to write my own history. This was the

mission he had shared with his first writer friend, Jack Kerouac. The Beats

made careers writing about themselves and their scene. In his middle years,

when I came to know him, Allen was still pushing the same project: you are

living history, you have to write it down.

At the time, I kept a diary, but

this writing is not a diary in the strict sense, it is rather a series of

scenes sketched from memory and presented in a more or less random sequence,

unstuck in time, like Billy Pilgrim.

*

I was twenty-one his fiftieth year. We met, two young men in the Jersey

barrens. I got sick, too much marijuana, he held my hand.

*

It's December 1980. Half way through a long tour, Allen Ginsberg, Peter

Orlovsky, and I are seated in the hanging tram that circles the German city of Wuppertal.

I'm writing in my diary.

–What you writing?

–I'm writing a book about us.

–What'll you call it?

—Travels With My Aunt.

There was a touch of meanness in my answer. On long tours, nerves fray. Nevertheless he approved. You

have to write your own history. No one's going to do it for you.

I didn't know it at the time, but my years of traveling with Allen did

mirror Graham Greene's fictional account of an Englishman who doesn't venture

much beyond his town house garden until he meets an aunt who shows him her

world; I was an English immigrant who hadn't ventured much beyond the Garden

State until I met an older man who showed me his.

*

Peter has gone down to the far end of the platform to smoke. Not dressed for

Germany in

December, Allen and I pace and shuffle in the swirling snowfall, collars turned

up against the cold. A train roars in.

–Frankfurt, it's going to Frankfurt.

–We're not going to Frankfurt.

He flushes, yelling.

–It's going to Frankfurt! It's going to Frankfurt!

–We're not going to Frankfurt!

A few commuters straggle out. The train pulls away.

The snow stops. Stars appear. We pace, smoke, shuffle some more.

As our train arrives, an old man approaches and introduces himself. He has

recognized Allen. He says he is a professor of literature.

The prof takes a window seat, I sit to his right. Allen sits opposite me,

arranging his book bag, winding a mic cable around his cassette recorder.

–You have been traveling. You must not have heard the news.

–What news?

–John Lennon was killed last night.

Allen crumples forward and weeps an eerie, wordless dirge into the machine.

*

At

the start, our respective realities were worlds apart, but our differences kept

us engaged, and we came to know each other well. We began with a few things in common.

We were both, in various ways, outsiders: he the queer son of a refugee mother,

I an immigrant having difficulty adapting. We both knew what it was to struggle

to get by. Our taste in literature and music was the same, though he had a more

intricate knowledge of the one and I of the other, and that made us a match. He

used to say he was my poetry teacher and I his music teacher. What struck me

most during our first conversations was that although he was older than my

father, he spoke as I and my friends did. Allen had pioneered the argot and

attitude that I had adopted as my own. He had played a key role in

disseminating the synthesis of white boy gossip and Harlem street jive that my generation

assumed it had invented.

*

He seemed strange, except in his intelligence and his art. That

I understood. But the temper, for one thing, the roaring rage of it, was

something the like of which I had not experienced before. I remember being in a

downtown bar at some kind of party. The place was packed and, somewhat oddly

for a bar, brightly lit. There he encountered a man a bit older than himself,

and they exchanged barely a word and he flew into a deafening rage. I'd never

heard anything like it. It vibrated one's whole being like some catastrophic

event, like an avalanche. The whole room rumbled with it, then went silent, and

the guy fled, and Allen was instantly back to normal, and the bar chatter

started up again as if nothing had happened. Allen told me the guy had been

part of a plot organized by the mayor's office, under the Lindsay

administration, to get him arrested on trumped-up drug charges, a plant and

bust scheme.

The temper was a real problem for me, though I never got a full-on dose

of it. I did get brief shots. We'd be on stage somewhere in the early

days, and he'd want Peter to do a couple of poems, and me to do a song part way

through the show. And I just didn't want to do it, but I'd sing because he'd

bark at me if I refused. –Speak, poet! The strongest dose I ever got was in

the spring of 1989, when my girlfriend was having heroin withdrawal, and I went

to him to ask for codeine, which I knew he had in his medicine kit. "On

your knees!" he roared, "Suck my cock for your dope!" It was

part anger, part laughter, part despair. And he immediately went calm and said,

"you'll only get her back on, using, you know." He was right, of

course.

Whatever strangeness there was about him for my own strange kid

sensibilities, we worked through it. I loved the guy for half my life. The

novelty, the disjunctions were what was fresh about the relationship. So what

was he like? Or, as he would say "give me a for instance." He was fearless, let's

start there.

*

We're coming out of a restaurant in Kassel

and suddenly he yells "NOOOO!" and flings himself into a crowd of men. They are

about to beat a guy up — a queer

bashing — he'd seen it and understood in a flash what was about to happen and

he didn't hesitate. The gang is stunned stock still. They disperse.

*

Fearlessness doesn't really describe it. It was faith in his own experience

and moral intelligence, exacerbated by a fascination with death. This was not a

guy with a lot of self-doubt. And it wasn't blind faith. He had tremendous

clarity. He understood himself because he'd worked at it and paid for it in

spades. He'd seen his mother go mad and had feared for his own sanity and had

spent a year in the bug house and been analyzed to hell and back and had taken

every drug under the sun and come through it all wiser. He'd been wrong, in the

sense of not fitting the standard mold of American manhood, in so many ways

over so many years, that he'd had to come through it or die, and he did come

through it. In his poem America,

he said "you made me want to be a saint." He had to become a saint. It was that or go mad.

*

He

was frugal. his father kept two sons and a mad wife in a series of

cheap apartments on a teacher's salary. The money, such as there was, went to doctors. When Naomi was in the various

hospitals, her men worried together in the same bed. I see Louie comforting the boys. Ruth Etting is on the radio singing, "Poverty may come to me it's true, but what care I, say, I'll get by, as long as I have you."

Everything

is saved. Plastic shopping bags are stashed in the pantry, saved to wrap books,

photographs, manuscripts and files for goings too and fro. Brown paper sacks are kept to

preserve bread. The tin box on the counter is full of small brown bundles; you

don't throw bread away. Shopping lists, laundry receipts are archive material.

You have to write your own history.

*

We

go to Eastern

Europe.

Our gigs are booked through the US Information Service, a cultural exchange

agency run by the State Department. I call it CIA lite. Our American contacts

in Warsaw are all embassy

officials. One, a pleasant, gray-haired guy who wears tennis sweaters and

loafers, is a spy — it's a standing joke. At one point the embassy throws a

party and we are introduced to various persons of importance — the head of

state radio, the head of state television, the head of state publishing. Next

day, a US official asks if we

want to meet "the underground." We are driven to a vacant apartment and told to

wait. We are picked up and driven to another vacant apartment across town and

told to wait. Finally we are driven to a loft in the center of Warsaw. Here we meet the

underground. They are the same people we had met the day before at the embassy,

plus a few fugitives who live at the loft. A couple of years later, the revolution

was announced because it was no longer possible to present the system and the underground as opposing entities. The black market had become the economy.

*

Allen

is a member of the PEN Club's Freedom to Write committee. While traveling, he investigates situations of censorship. We have

heard that the editor of the Solidarity newspaper has been jailed, is ill, and

is not receiving proper care. We march into the military prison, present our

PEN credentials, and demand to see the prisoner. The officer in charge is furious,

red faced, beside himself. We are not admitted.

*

I

arrive at Allen's, let myself in, and meet Gregory Corso. He

strikes a boxing stance and says, "show me your hands!," the words bent

into a peculiar music by his toothlessness. I hold out my hands, palms up. He

says "you look like puckin Saint Prancis. You're gonna get yr ass kicked!"

This is the standard

greeting. You just have to ride it out. His follow-up routine is

–Are

you a poet?

The

young respondent typically hedges.

–Are

you a poet or not? If you are a poet, you should say so.

–Yes.

I'm a poet.

–So

tell me a poem.

More

hedging.

–You're

a poet and you can't puckin tell me a poem? Listen to this. A star is as far

as the eye can see and as

near as my eye is to me.

*

Owsley comes by the apartment and drops off a large jar of clear liquid.

Over a period of months, once a week or so, we open the fridge and

stand there, looking at the jar on the top shelf among the left-overs.

–Are we going to do it?

Are we going to do it in a 100-square-foot slum kitchen in stifling New York August? No thanks. Been there done that. We parcel it out to visitors.

*

I

play a string of gigs in Scandinavia with the Fugs, and then

fly to Macedonia to meet Allen at the

Struga festival. They're going to give him this year's laurel crown. The flight

from the capital into the mountains is all nervous men with moustaches. As the plane

taxis for takeoff, they all light up. They smoke all the way to Struga and

applaud when the plane lands. At the luggage claim, I am approached by two

beautiful young women and an older man, presumably their father. He asks if I

am Steve from the United States. I say yes, and am

warmly welcomed by all. Follow me, he says. Just then, two young men introduce

themselves as the festival guys come to pick me up. Apparently there was

another American Steve on the flight. I sometimes imagine how it might have been to

drive off into the mountains with pops, marry one of the girls, and spend the

rest of my days tending a vineyard. As it happened, I was driven to a hotel on

a lake where, strangely, I find the lower east side poet crew in the bar. Alan Ansen is in from Athens. His luggage has been

lost and he spends several days ripening in a frayed, too-small black suit.

We

are mindful of the recent nuclear accident at Chernobyl, but I have the sense of the helplessness of the people to avoid contamination,

and let my guard down. What, not swim in the lake, not eat and drink? We are

told that the nuclear contamination will wash off this year's produce, but will

be inside next year's. Berries, mushrooms, and deer meat are off menus all over

Europe.

Suomo,

a drum maker, tells us that he and his children had been in the yard of his

house in eastern Poland. It was a warm, clear

day and the children were playing naked in the grass. Suddenly, he said, he felt

a fine drizzle coming from a cloudless sky and, looking up at the treetops, saw the

leaves curling up like clenched fists. He hurried the

children inside and called various authorities, but no one could explain what

was going on. Within a couple of hours, medical teams were going door-to-door handing

out iodine tablets. Later, Allen and I sit in the airport writing a song about nuclear melt down as sullen police deconstruct our luggage.

*

We have an afternoon off in Philadelphia

and decide to go to the movies. Woody Allen's got a new film out. Al laughs at odd times. An ordinary scene of a guy

getting into a taxi is somehow hilariously funny. It's as if he's operating on

a different frequency from everyone else. There's something child-like about

it, like I'm there with my seven-year-old son and have to explain the jokes. Later,

we go to see a new movie of La Traviata, and he sings the overture, waving his

arms about, punching the air. He can't contain himself.

*

I take him to meet my parents. On the bus out to Jersey, I tell him that the local iron mines produced cannon

balls for Washington's artillery.

He begins to write the poem Garden State. After dinner, he puts his

cigarette out on his plate. I see my brother think, "the barbarian American."

We pile into my mother's enormous blue Plymouth

and drive the couple of miles to Greystone mental hospital. Inside the gate, we cruise up the long smooth blacktop between acres of perfect lawn. He says, "this is where I used to sit with my

mother," and he breaks down, the sensitive kid picnicking with mad Naomi,

smiling, trying to act like everything is fine, and the great man weeping in

the back seat of the absurd vehicle.

Generosity. That night, we are to give a performance at the local county college. My

whole family is in the audience. I'm afraid he'll read his new poem about dirty sex, but backstage, as we're preparing to go on, he hands me his books. –You pick the

program tonight.

*

Generosity again. I have a series of recording sessions in Chelsea.

One night, after a fourteen-hour session, about 2

a.m., I'm taking the A Train uptown to my place in Washington

Heights. Next to me, leaning

against the seat are two gig bags — my bass and my guitar. On the seat is my

briefcase. Like an idiot, I have my face buried in a newspaper. At 125th

St., a kid comes out of nowhere, grabs the bass and dashes into the next car, I

stand up to take off after him as another kid comes from the other direction

and runs off with my guitar. I turn to pursue him and someone shouts "your

briefcase!" In a flash I know the charts for the sessions are worth more

than the guitars and I hesitate. The train stays in the station, doors open,

and I know I'm not going to get in a fight with a couple of kids in the middle

of the night in Harlem.

Next day I tell Allen what happened. He says, –The only way you're going to

get over it is to replace the instruments. What'll it cost? –About a thousand.

–OK.

This is not a guy who makes a lot of money, and he's replacing my

instruments. Next day I go to Manny's and feel a lot better.

*

His voice on the message

machine: Allen Ginsberg

Beth Israel Hospital.

Important. Please call back as soon as possible. If this is the wrong number,

please leave a message for Steven Taylor at Naropa, at the poetics office,

thank you.

I call back and he says –liver biopsy, hepatitis C, cancer

untreatable with chemicals or surgery. I feel equanimity, I guess all those

years of Buddhist practice paid off. The doctor says four five months but I

feel maybe one or two.

He says carry on! I always loved you. He says I'll miss you, and I register

how odd that sounds. I'll miss you too, I say.

Three hours later in a synagogue basement in Denver

I crack a dusty old volume untouched for generations and read.

There is nothing under heaven, saving a true friend

unto which my heart doth lean. And this dear freedom hath begotten me this

peace, that I mourn not for that end which must be, nor spend one wish to have

one minute added to the uncertain date of my years.