This article originally appeared on The Archdruid Report

One of the least constructive

habits of contemporary thought is its insistence on the uniqueness of the modern

experience. It's true, of course, that fossil fuels have allowed the world's

industrial societies to pursue their follies on a more grandiose scale than any

past empire has managed, but the follies themselves closely parallel those of

previous societies, and tracking the trajectories of these past examples is one

of our few useful sources of guidance if we want to know where the current

versions are headed.

The metastasis of money through

every aspect of life in the modern industrial world is a good example. While no

past society, as far as we know, took this process as far as we have, the

replacement of wealth with its own abstract representations is no new thing. As

Giambattista Vico pointed out back in the 18th century, complex societies move

from the concrete to the abstract over their life cycles, and this influences

economic life as much as anything else. Just as political power begins with raw

violence and evolves toward progressively more subtle means of suasion,

economic activity begins with the direct exchange of real wealth and evolves

through a similar process of abstraction: first, one prized commodity becomes

the standard measure for all other kinds of wealth; then, receipts that can be

exchanged for some fixed sum of that commodity become a unit of exchange;

finally, promises to pay some amount of these receipts on demand, or at a fixed

point in the future, enter into circulation, and these may end up largely

replacing the receipts themselves.

This movement toward abstraction

has important advantages for complex societies, because abstractions can be

deployed with a much smaller investment of resources than it takes to mobilize

the concrete realities that back them up. We could have resolved last year's

debate about who should rule the United States the old-fashioned way, by having

McCain and Obama call their supporters to arms, march to war, and settle the

matter in battle amid a hail of bullets and cannon shot on a fine September day

on some Iowa prairie. Still, the cost in lives, money, and collateral damage

would have been far in excess of those involved in an election. In much the

same way, the complexities involved in paying office workers in kind, or even

in cash, make an economy of abstractions much less cumbersome for all concerned.

At the same time, there's a trap

hidden in the convenience of abstractions: the further you get from the

concrete realities, the larger the chance becomes that the concrete realities

may not actually be there when needed. History is littered with the corpses of

regimes that let their power become so abstract that they could no longer

counter a challenge on the fundamental level of raw violence; it's been said of

Chinese history, and could be said of any other civilization, that its basic

rhythm is the tramp of hobnailed boots going up stairs, followed by the whisper

of silk slippers going back down. In the same way, economic abstractions keep

functioning only so long as actual goods and services exist to be bought and

sold, and it's only in the pipe dreams of economists that the abstractions

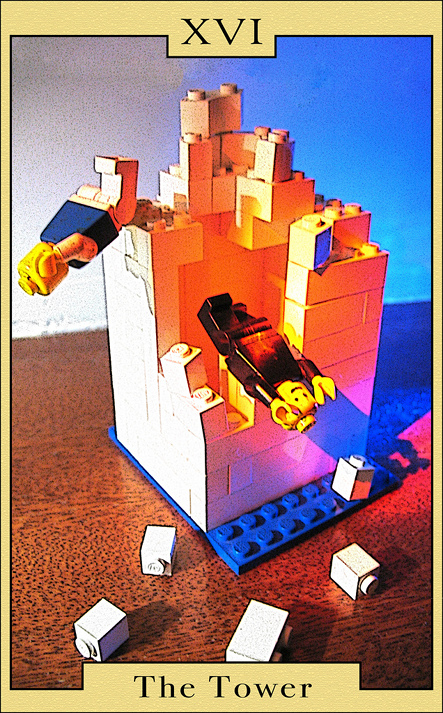

guarantee the presence of the goods and services. Vico argued that this trap is

a central driving force behind the decline and fall of civilizations; the

movement toward abstraction goes so far that the concrete realities are

neglected. In the end the realities trickle away unnoticed, until a shock of

some kind strikes the tower of abstractions built atop the void the realities

once filled, and the whole structure tumbles to the ground.

We are uncomfortably close to such

a possibility just now, especially in our economic affairs. Over the last

century, with the assistance of the economic hypercomplexity made possible by

fossil fuels, the world's industrial nations have taken the process of economic

abstraction further than any previous civilization. On top of the usual levels

of abstraction — a commodity used to measure value (gold), receipts that could

be exchanged for that commodity (paper money), and promises to pay the receipts

(checks and other financial paper) — contemporary societies have built an

extraordinary pyramid of additional abstractions. Unlike the pyramids of Egypt,

furthermore, this one has its narrow end on the ground, in the realm of actual

goods and services, and widens as it goes up.

The consequence of all this

pyramid building is that there are not enough goods and services on Earth to

equal, at current prices, more than a small percentage of the face value of

stocks, bonds, derivatives, and other fiscal exotica now in circulation. The

vast majority of economic activity in today's world consists purely of

exchanges among these representations of representations of representations of

wealth. This is why the real economy of goods and services can go into a

freefall like the one now under way, without having more than a modest impact

so far on an increasingly hallucinatory economy of fiscal abstractions.

Yet an impact it will have, if the

freefall proceeds far enough. This is Vico's point, and it's a possibility that

has been taken far too lightly both by the political classes of today's

industrial societies and by their critics on either end of the political

spectrum. An economy of hallucinated wealth depends utterly on the willingness

of all participants to pretend that the hallucinations have real value. When

that willingness slackens, the pretense can evaporate in record time. This is

how financial bubbles turn into financial panics: the collective fantasy of

value that surrounds tulip bulbs, or stocks, or suburban tract housing, or any

other speculative vehicle, dissolves into a mad rush for the exits. That rush

has been peaceful to date; but it need not always be.

I've argued in previous articles

that the industrial age is in some sense the ultimate speculative bubble, a

three-century-long binge driven by the fantasy of infinite economic growth on a

finite planet with even more finite supplies of cheap abundant energy. Still, I

am coming to think that this megabubble has spawned a second bubble on nearly

the same scale. The vehicle for this secondary megabubble is money — meaning

here the entire contents of what I've called the tertiary economy, the

profusion of abstract representations of wealth that dominate our economic life

and have all but smothered the real economy of goods and services, to say nothing

of the primary economy of natural systems that keeps all of us alive.

Speculative bubbles are defined in

various ways, but classic examples — the 1929 stock binge, say, or the late

housing bubble — have certain standard features in common. First, the value of

whatever item is at the center of the bubble shows a sustained rise in price

not justified by changes in the wider economy, or in any concrete value the

item might have. A speculative bubble in money functions a bit differently than

other bubbles, because the speculative vehicle is also the measure of value;

instead of one dollar increasing in value until it's worth two, one dollar

becomes two. Where stocks or tract houses go zooming up in price when a bubble

focuses on them, then, what climbs in a money bubble is the total amount of

paper wealth in circulation. That's certainly happened in recent decades.

A second standard feature of

speculative bubbles is that they absorb most of the fictive value they create,

rather than spilling it back into the rest of the economy. In a stock bubble,

for example, a majority of the money that comes from stock sales goes right

back into the market; without this feedback loop, a bubble can't sustain itself

for long. In a money bubble, this same rule holds good; most of the paper

earnings generated by the bubble end up being reinvested in some other form of

paper wealth. Here again, this has certainly happened; the only reason we

haven't see thousand-percent inflation as a result of the vast manufacture of

paper wealth in recent decades is that most of it has been used solely to buy

even more newly manufactured paper wealth.

A third standard feature of

speculative bubbles is that the number of people involved in them climbs

steadily as the bubble proceeds. In 1929, the stock market was deluged by

amateur investors who had never before bought a share of anything; in 2006,

hundreds of thousands, perhaps millions, of people who previously thought of

houses only as something to live in came to think of them as a ticket to

overnight wealth, and sank their net worth in real estate as a result. The

metastasis of the money economy discussed in previous posts here is another

example of the same process at work.

Finally, of course, bubbles always

pop. When that happens, the speculative vehicle du jour comes crashing back to

earth, losing the great majority of its assumed value, and the mass of amateur

investors, having lost anything they made and usually a great deal more,

trickle away from the market. This has not yet happened to the current money

bubble. It might be a good idea to start thinking about what might happen if it

does so.

The effects of a money panic would

be focused uncomfortably close to home, I suspect, because the bulk of the

hyperexpansion of money in recent decades has focused on a single currency, the

US dollar. That bomb might have been defused if last year's collapse of the

housing bubble had been allowed to run its course, because this would have

eliminated no small amount of the dollar-denominated abstractions generated by

the excesses of recent years. Unfortunately the US government chose instead to

try to reinflate the bubble economy by spending money it doesn't have through

an orgy of borrowing and some very dubious fiscal gimmickry. A great many foreign

governments are accordingly becoming reluctant to lend the US more money, and

at least one rising power — China — has been quietly cashing in its dollar

reserves for commodities and other forms of far less abstract wealth.

Up until now, it has been in the

best interests of other industrial nations to prop up the United States with a

steady stream of credit, so that it can bankrupt itself filling its

self-imposed role as global policeman. It's been a very comfortable

arrangement, since other nations haven't had to shoulder more than a tiny

fraction of the costs of dealing with rogue states, keeping the Middle East

divided against itself, or maintaining economic hegemony over an increasingly

restive Third World, while receiving the benefits of all these policies. The

end of the age of cheap fossil fuel, however, has thrown a wild card into the

game. As world petroleum production falters, it must have occurred to the

leaders of other nations that if the United States no longer consumed roughly a

quarter of the world's fossil fuel supply, there would be a great deal more for

everyone else to share out. The possibility that other nations might decide

that this potential gain outweighs the advantages of keeping the United States

solvent may make the next decade or so interesting, in the sense of the famous

Chinese curse.

Over the longer term, on the other

hand, it's safe to assume that the vast majority of paper assets now in

circulation, whatever the currency in which they're denominated, will lose

essentially all their value. This might happen quickly, or it might unfold over

decades, but the world's supply of abstract representations of wealth is so

much vaster than its supply of concrete wealth that something has to give

sooner or later. Future economic growth won't make up the difference; the end

of the age of cheap fossil fuel makes growth in the real economy of goods and

services a thing of the past, outside of rare and self-limiting situations. As

the limits to growth tighten, and become first barriers to growth and then

drivers of contraction, shrinkage in the real economy will become the rule,

heightening the mismatch between money and wealth and increasing the pressure

toward depreciation of the real value of paper assets.

Once again, though, all this has

happened before. Just as increasing economic abstraction is a common feature of

the history of complex societies, the unraveling of that abstraction is a

common feature of their decline and fall. The desperate expedients now being

pursued to expand the American money supply in a rapidly contracting economy

have exact equivalents in, say, the equally desperate measures taken by the

Roman Empire in its last years to expand its own money supply by debasing its

coinage. The Roman economy achieved very high levels of complexity and an

international reach; its moneylenders – we would call them financiers today –

were a major economic force, and credit played a sizeable role in everyday

economic life. In the decline and fall of the empire, all this went away. The

farmers who pastured their sheep in the ruins of Rome's forum during the Dark

Ages lived in an economy of barter and feudal custom, in which coins were rare

items more often used as jewelry than as a medium of exchange.

A similar trajectory almost certainly

waits in the future of our own economic system, though what use the shepherds

who pasture their flocks on the Mall in the ruins of a future Washington DC

will find for vast stacks of Treasury bills is not exactly clear. How the

trajectory will unfold is anyone's guess, but the possibility that we may soon

see sharp declines in the value of the dollar, and of dollar-denominated paper

assets, probably should not be ignored, and cashing in abstract representations

of wealth for things of more enduring value might well belong high on the list

of sensible preparations for the future.

Image by herval, courtesy of Creative Commons license.