Blissed-out, ecstatic union with our divine selves — we seek it at raves and rock concerts, and in the desert with the Burning Man. I try to get there when I'm jamming with my band — but I didn't realize until I wrote The Language of the Blues: From Alcorub to Zuzu how much this longing relates to Voodoo, and the concept of possession.

Vodou (the proper Kreyol/Creole spelling of Voodoo) is a neo-African religion that evolved in the New World from the 6.000-year-old West African religion Vodun. This was the religion of many slaves brought from West Africa to the Americas and the Caribbean. Vodun was brutally repressed by slave-owners, yet its powerful ethics and aesthetics endured. We owe our concepts of cool, soul and even rock and roll to it.

The roots of rock are in a West African word for dance — rak. And as Michael Ventura wrote in his important essay on rock music, "Hear that Long Snake Moan": "The Voodoo rite of possession by the god became the standard of American performance in rock'n'roll. Elvis Presley, Little Richard, Jerry Lee Lewis, James Brown, Janis Joplin, Tina Turner, Jim Morrison, Johnny Rotten, Prince — they let themselves be possessed not by any god they could name but by the spirit they felt in the music. Their behavior in this possession was something Western society had never before tolerated."

Vodou possession is not the hokey demon-possession of zombie movies; it's a state of union with the divine achieved through drumming, dancing and singing. It's becoming "filled with the Holy Ghost" in the Pentecostal Christian tradition, reaching Buddhist nirvana, or attaining the yogi's Samadhi.

In the Yoruba culture of West Africa, this ability to connect with one's inner divinity is called coolness (itutu). In traditional Yoruba morality, generosity indicates coolness and is the highest quality a person can exhibit. In American culture, we say someone is cool, or that a musician "has got soul." We notice "Southern hospitality."

The Trans-Atlantic slave trade carried these ideas to the New World, particularly as slavers burrowed inward from Senegambia on the West African coast to the Kingdom of Dahomey, a Vodun stronghold.

Dahomey spread across much of today's Togo, Benin and Nigeria and became heavily involved in the slave trade. Vodun practitioners were sent overseas by the thousands, for example, when the Fon people of what is now Benin conquered their neighbors, the Ewe, in 1729 and traded prisoners to European slave ships. Many Fon were also kidnapped and traded into slavery.

Vodu is a Fon-Ewe word meaning spirit, or deity. Vodun is God or Great Spirit. This supreme creator was an all-powerful, unknowable, creative force represented as the giant snake Dan carrying the universe in its coils. Today, in Haiti and in American Vodou strongholds like New Orleans, Dan is worshipped as Damballah, the Grand Zombie (the Bantu word nzambi means God). He's John Lee Hooker's Crawling Kingsnake.

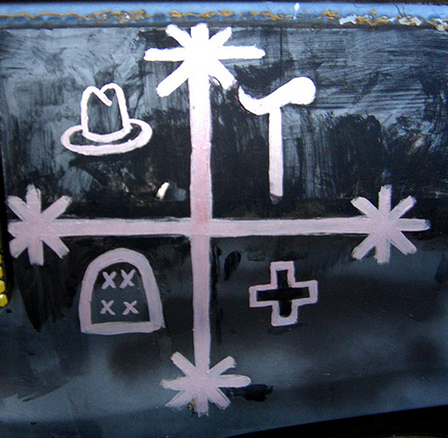

Branching off from this almighty God-force are spirit-gods called loa. During Vodou ceremonies, a loa may descend the center post of the temple to possess or "ride" a worshipper who has reached a sufficiently high state of consciousness. The morality implicit in this is stated in the Haitian proverb, "Great gods cannot ride little horses."

Vodun practices like drumming were definitely noticed by nervous colonists who had imported fierce warriors and tribal priests to work their farms. After a deadly rebellion in the South Carolina colony in 1739, the colonists realized slaves were using talking drums to organize resistance. The Slave Act of 1740 in South Carolina barred slaves from owning or using "drums, horns, or other loud instruments." Other colonies followed suit with legislation against the use of drums by slaves, such the Black Codes of Georgia.

Soon, religious repression was in full swing. Slaves caught praying were brutally penalized, as this excerpt from Peter Randolph's narrative "Slave Cabin to the Pulpit" recounts:

"In some places, if the slaves are caught praying to God, they are whipped more than if they had committed a great crime. The slaveholders will allow the slaves to dance, but do not want them to pray to God. Sometimes, when a slave, on being whipped, calls upon God, he is forbidden to do so, under threat of having his throat cut, or brains blown out."

Vodun practitioners taken as slaves to plantations in Haiti, Cuba, Brazil, and Jamaica were also harshly prohibited from practicing their religion. But enslaved Vodun priests arriving in the largely Catholic West Indies quickly grasped the similarity between their tradition of appealing to loa to intercede in their favor with the Almighty, and Catholics praying to their saints for intercession with God. By superimposing Catholic saints over the loa, slaves created a hybrid religion called Santeria (saint worship) in the Spanish Islands and Vodou in Haiti.

On August 22, 1791, Haitian slaves revolted, guided by Vodou priests who gave the signal to begin the rebellion and consulted their oracle to determine which military strategies would succeed. The revolutionaries defeated an army sent by Napoléon Bonaparte. They declared independence on January 1, 1804, and established Haiti as the world's first black republic.

In 1809, Vodou arrived in the United States en masse when Haitian slave owners who had fled to Cuba with their slaves during the Haitian Revolution were expelled from Cuba. Most relocated to the French- and Spanish-speaking port city of New Orleans, nearly doubling its size in one year. Today, fifteen percent of the population of New Orleans practices Vodou. It is also popular in other North American cities with significant African and Haitian communities.

Among the Haitians arriving in Louisiana was Marie Laveau, who became the leader of New Orleans Vodou practitioners in 1820 when she was elected the human representative of the Grand Zombie. (Fun fact: former White House Social Secretary Desirée Rogers is descended from Marie Laveau.)

Laveau kept a python named Zombi, and danced with it on her shoulders during the ceremonies over which she presided – an image appropriated, with other Vodou nods, for Britney Spears's performance of "I'm a Slave 4 U" at the 2001 MTV Video Music Awards.

Threatened by the successful slave revolt, the United States and Western Europe slapped economic sanctions on Haiti. These turned the prosperous colony into an impoverished state that couldn't sell the products of its fields. The sensationalistic 1884 book Haiti or the Black Republic by Sir Spencer St. John, slammed Vodou as an evil cult. The book contained gruesome descriptions of human sacrifice, cannibalism, and black magic–some extracted from Vodou priests by torture à la the Spanish Inquisition. It was a popular source for Hollywood screenwriters who began churning out voodoo horror flicks in the 1930s.

The first rock artist to embrace zombie imagery was Screamin' Jay Hawkins (born Jalacy Hawkins in Cleveland in 1929), who would rise from a coffin onstage in a cloud of dry ice fog. Hawkins had intended to record "I Put A Spell On You" as a soulful blues ballad. But once the producer "brought in ribs and chicken and got everybody drunk, we came out with this weird version," Hawkins admitted, adding "I found out I could do more destroying a song and screaming it to death." Hawkins kicked off the undead craze among rockers and Goths from Alice Cooper to Marilyn Manson.

Meanwhile, African Americans had grafted Vodun rites onto the Southern black Baptist church. Descriptions of African American church services in the late 1800s and early 1900s depict members of the congregation dancing in a circle around a center table, in a "rock" or "ring shout" as they follow the deacon, who bears a standard.

It was the deacon's job to whip the parishioners into a frenzy. Once people were fainting and speaking in tongues, that was called "rocking the church." The concept of a deity "riding" with a worshipper transferred to these Christian churches, where the cry "Drop down chariot and let me ride!" was often heard, as well as "Ride on!" and "Ride on, King Jesus!"

In West African tradition, loa like to hang at a cross roads. Robert Johnson recorded "Cross Road Blues" in San Antonio, Texas, on November 27, 1936. In the first verse, Johnson describes traveling to the cross roads and falling to his knees, crying out to God to save him. In the second verse, he stands and tries to flag a ride as dusk descends.

Standing at the cross roads, I tried to flag a ride

Didn't nobody seem to know me, everybody pass me by

Johnson's genius for metaphor and his intellectual sophistication made his songs classics. What's especially striking about "Cross Road Blues" is Johnson's expressed sense of failure at having dug into his spiritual resources and come up empty handed. Rather than giving us a pat story of being overwhelmed by the devil or raised to the heavens by God, Johnson stands at the crossroads, sinking down, crushed by existential dread. Christianity has failed him, and the loa are passing him by. The rites that might have taught him how to call for that ride are lost to him.

Yet, the enduring power of his own music proves that the Africans brought here as slaves carried with them incredibly strong aesthetic, ethical and cultural values that not only withstood the shock of their forced transplantation to the New World, but transformed and invigorated it. Africa's influence is what makes the United States uniquely American, and is why we respond to that Voodoo beat.

Image by battyward, courtesy of Creative Commons license.