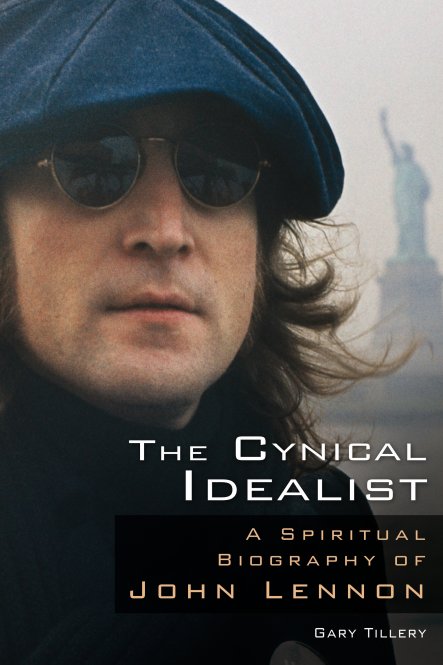

The following is excerpted from The Cynical Idealist: A Spiritual Biography of John Lennon (Quest Books, December 2009).

Consider the pieces of decorated paper in your wallet that give you the power to walk into a shop you’ve never visited before and leave with whatever strikes your fancy. Consider how traffic laws are observed on a normal day in the city versus how they are observed while a riot is taking place. Consider how you behave when surrounded by thoughtful, polite people, but how petty you would become if marooned somewhere with a group of self-gratifying, devious individuals.

Human society is founded on agreement. Paper money has power only as long as everyone agrees on its value. Laws are relevant only as long as a significant percentage of people agree to observe them. Each of us has a set of values we find valid, but if the group surrounding us is playing by a different set of rules, we’ll find it extremely difficult to resist conforming.

What we agree on shapes society. Once enough of us agree that character is more important than skin color, racism will tend to vanish. Once enough of us agree that it is absurd to pay a woman and a man different wages for performing the same job, gender bias will tend to wither away. Once enough of us agree that cigarette smoke is harmful, the acceptability of smoking will tend to diminish.

Now, what if a significant number of us were to agree that — starting next Monday — we would treat everyone we encountered with respect, compassion, and love?

John Lennon realized, then propounded, that since as humans we have the ability to change our own habits and convictions, the only barrier to our living in a better world is agreement that we are committed to it. He implied the concept in “All You Need Is Love,” “Instant Karma (We All Shine On),” and “Happy Xmas (War Is Over).” However, he crystallized his point of view in his masterpiece, “Imagine.” In simple but resonating lyrics, he sketched the framework of a harmonious world he and other dreamers had in mind, concluding with an invitation to the listener to join them.

Then he read a book called Mind Games, by Robert Masters and Jean Houston, published in 1972. Just as the Maharishi had come along at precisely the right moment in Lennon’s life, echoing his point of view plus offering a proven method to help reach the goal he wanted to reach, Masters and Houston confirmed Lennon’s own insights about psychic exploration and provided a structured process to help others expand their consciousness.

The authors had been involved in LSD research in the 1960s. After the government ceased to license such research, they developed alternative approaches to mind exploration based on meditation, assisted trance, and guided imagery.

In Mind Games they set forth a series of mental adventures for small groups designed to tap into four levels of the psyche: the sensory, the psychological, the mythic, and the spiritual. They placed the “games” in the tradition of mystery schools of the distant past; seekers could find personal meaning and enlightenment in decoding the symbolic language of their own dreams and trance images and, by use of creative visualization, could improve their daily lives and stretch their own boundaries of what they thought possible.

The objective was to learn to access the unconscious mind for creative solutions to conscious problems. Not only was the unconscious mind a rich and endless resource that could be called upon whenever needed, but working within a deep trance a person could take advantage of an entirely different unreeling of time. That is, a clock in the room might register the passage of five minutes, but the perception of that elapsing time to someone who is meditating can be tremendously distorted. In five minutes of a trance state, a person might mentally rehearse an hour-long speech or go on a yearlong quest in search of the Holy Grail.

By means of the mind games in the book, participants could free themselves from negative attitudes and inhibitions and become more creative, more confident, and more mentally adventurous. In short, they could become more fully realized human beings.

The training ignited Lennon’s imagination. He saw it leading to a cadre of mentally liberated people infiltrated throughout a less-enlightened society — “mind guerrillas” working toward a higher purpose than their contemporaries and having a positive influence on them. To him, expanding legions of mentally liberated people would inevitably build the level of agreement necessary to bring into existence the peaceful society that was his goal.

He wrote a song of encouragement, also titled “Mind Games.” Speaking in the language of dreams (clearly Lennonesque language and Lennonesque dreams), he equated the mind games process with pagan rites. In terms such as “druid dudes,” “ritual dance,” and “stones of your mind,” he evoked the Salisbury Plain-initiates surrounded by trilithic arches, ritualized motion, earnest chanting, and communal commitment.

To those who were beginning to believe that the spirit of the sixties had died, he was advising: don’t give up, keep on; keep chanting the mantra of peace and love. Let’s work together as an invisible army. We’ll use the power of visualization — some call it magic — to project our image of peace in space and time. We’ll create an “absolute elsewhere” in our minds, an ideal so detailed and realistic that our intentions will make it manifest.

Just as athletes, speakers, entertainers — people from all walks of life — were beginning to discover the power of visualization to improve their real-life performance, Lennon suggested that peace could be manifested in the real world through the concerted efforts of individuals to visualize it.

Lennon and Ono even had a name for the absolute elsewhere, and a description. On April 1, 1973, they held a press conference to reveal them. The media assembled as requested, expecting some newsworthy comment regarding the couple’s ongoing struggle to avoid deportation from the United States. Instead they listened to the following declaration: “We announce the birth of a conceptual country, NUTOPIA. Citizenship of the country can be obtained by declaration of your awareness of NUTOPIA. NUTOPIA has no land, no boundaries, no passports, only people. NUTOPIA has no laws other than cosmic. All people of NUTOPIA are ambassadors of the country. As two ambassadors of NUTOPIA, we ask for diplomatic immunity and recognition in the United Nations of our country and its people.”

The subtlety of the artistic concept was like enciphered text to most of those who had gathered to report the announcement, as well as to the fans who read it afterward — even when the declaration was reprinted on the album sleeve for Lennon’s Mind Games. It seemed that almost no one comprehended the idea they were advancing. However, what had the hallmarks of a simple April Fools’ Day joke on the media (and it was, on one level) actually had much deeper import.

NUTOPIA was a proposed emotional, intellectual, and spiritual union of people. It would be an imaginary union, but certainly no more imaginary than the artificial boundaries that separated people in the “real” world. According to the announcement, an individual could become a citizen of the conceptual country simply by declaring his or her awareness of it — in other words, by understanding what Lennon and Ono were trying to communicate between the lines. (Perhaps behind the words would be more accurate.)

“Citizens” of NUTOPIA would recognize how absurd and artificial it was to place labels on human beings: black, white, yellow, red, Japanese, British, Congolese, American, Muslim, Christian, Jew, Buddhist, conservative, liberal, socialist, capitalist, etc. Absurd because, for example, how do we categorize the offspring of a black man and a yellow woman? Or a Japanese woman who emigrates and becomes a British or American citizen? Or a Jew who converts to Christianity and later converts again to Buddhism? Is any label applied to an individual as important as his character? As important as how much personal integrity she possesses? As important as how compassionate and considerate the person is?

Citizens of NUTOPIA would mutually recognize their common humanity and their preference for peace and harmony, and they would interact in accordance with cosmic laws. Cosmic laws because those are the laws that make up our innate sense of justice. To kill each other or not to kill each other? Steal from or not steal from? Respect or not respect? Cosmic laws make sense to us, as opposed to: we should not kill except when the act is sanctioned by the proper political or religious leader, or we should never steal unless the legal machinery says that it is permissible this time (the Indians are being relocated to another region — stake out the land you want), etc.

As a citizen of NUTOPIA — that is, someone who “got it” — each individual would be an example and a proponent of the common human bond. Each would qualify to serve as an ambassador to those who had not yet gotten it.

Lennon ended the statement with his customary whimsy (much as he had ended the note returning his MBE medal with a reference to “Cold Turkey” slipping down the charts). He and Yoko asked the UN for diplomatic immunity and recognition.

The very name of the imaginary country was whimsical, as well as being cryptically self-referential for Lennon. NUTOPIA — New Utopia — was of course a modern version of the land Sir Thomas More invented in the book he published in 1516. More coined the word Utopia from two Greek words, ou (not) and topos (place) — that is, “no place”-or “nowhere.” As a citizen of NUTOPIA, then, Lennon officially became a Nowhere Man.

Those perceptive listeners who understood and embraced the absolute elsewhere of NUTOPIA would constitute the invisible army Lennon described in “Mind Games.” Acting individually, but in concert, they would bring about a more harmonious world through communal visualization.

The book Mind Games inspired Lennon’s song, but his source of inspiration for the technique of visualization was Yoko Ono. She had been telling him about it, he said, since they met. The technique has an occult derivation, the idea being that on some ethereal level we are constantly in contact with the forces of the universe and that our heartfelt wishes, our prayers, communicate through the cosmos and can attract to us what we desire. A more mundane explanation is that if we focus on something we truly want, our subconscious mind will take the hint and work toward arranging it for us (i.e., if we wish passionately for riches or love or health, we will tend to motivate ourselves and be attracted to situations or behavior or opportunities that will make that outcome feasible).

Of course, the technique has its dark side. We can focus so much psychic energy on one goal — riches, for instance — that while it is becoming reality we lose our health or family. On a macro scale the implications are correspondingly greater. Wherever a society’s collective imagination is focused will tend to gain power and inevitability. If that is a looming depression or foreign threat or shortage of an important resource, we can create through our words and actions the very outcome we dread.

Because Lennon believed that we all “shine on,” he felt that each of us bears responsibility for part of the problem. “If you speak, what you say doesn’t end here. I believe scientists could prove that vibrations go on and on infinitely, and therefore every action goes on and on infinitely and has its effect. If you carefully think out the effect you’re going to create, there’s more chance for all of us. It’s hard to think of your every move. But your attitudes to life will have an effect on everyone — and thereby, the universe.”

Once, while commenting on a radio report about a demonstration against nuclear power, he provided an excellent example, on a smaller scale, of the problem of misdirected focus. Without being conscious of the fact, he said, the protesters taking part in the demonstration were calling more media attention — and ultimately more attention by the general public — to the very industry they opposed. They were giving it greater power. However, regardless of how laudable their goal, everyone knew that the energy produced was essential. Therefore, their efforts were counterproductive and their positive energy squandered. Lennon argued that what they ought to be doing was devoting the same time and resources to finding and calling attention to an alternative. They ought to be focused on the solution.

The coin had two sides. Just as the collective focus could become the problem, it also presented an opportunity.

Consistent with his own insight, Lennon had already used the principle of collective visualization to plant a positive image in the public psyche. He had already written a song that offered his solution, his alternative to the nightmarish futures on which the people of his era were focused — the endless quagmire of Vietnam, world famine, Orwell’s 1984, nuclear winter, apocalypse in the Middle East — as well as his prescription to end the perennial strife of our species.

He recorded and released it in 1971, a song that would become his most famous anthem.

Gary Tillery was born in Phoenix in 1947. He served in Vietnam with the United States Air Force (1968-69). After two decades in the business world, he turned his time and energy to his lifelong passion for literature and art, producing a collection of stories set in Vietnam titled Darkling Plain, and a series of detective novels. Tillery is also a sculptor. His best-known work is the sculpture for the Vietnam Memorial in Chicago, the bronze bust of Steve Allen for the Steve Allen Theater in Hollywood, and the life-size bronze of Luis Aparicio at U. S. Cellular Field. Find Gary Tillery on Twitter @garytilleryart and on Facebook garytillery.com