How do you know but that ev’ry Bird that cuts the airy way,

Is an immense world of delight, clos’d by your senses five?

–William Blake

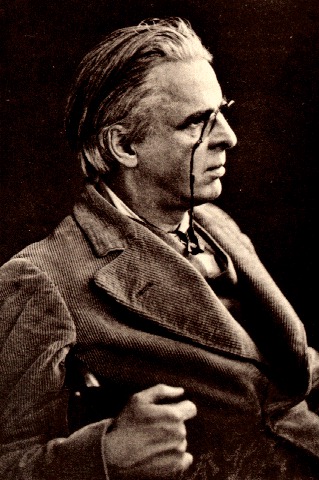

William Butler Yeats, the celebrated Irish poet, was a little cuckoo and a lot genius. His mystical beliefs about life and the soul seem strange to some, but his poems and ideas have influenced many contemporary thinkers. Yeats himself might have suggested that there was a connection between the cuckoo and the genius–that perhaps you have to be some kind of strange bird to uncover immense, visionary worlds of prophecy, torment, and delight.

In his 1919 poem, “The Second Coming,” Yeats turned his gaze to the future. He suggested that we are reaching the end of one historical cycle–and that the passage into another would be full of violence, division, and uncertainty.

Turning and turning in the widening gyre

The falcon cannot hear the falconer;

Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold

The ceaseless “turning and turning” depicts a world spiraling way out of balance. We humans are the falcons, and we are dangerously far from a guiding source of power and love vital to our well-being.

Yeats’ poems drench the reader in a storm of language and imagination. They dazzle and penetrate with a force rarely seen this side of William Shakespeare.

Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world,

The blood-dimmed tide is loosed, and everywhere

The ceremony of innocence is drowned;

The best lack all conviction, while the worst

Are full of passionate intensity.

Surely some revelation is at hand;

Surely the Second Coming is at hand.

Some critics have interpreted such lines as “the blood-dimmed tide is loosed” and “the worst are full of passionate intensity” as foretelling the rise of statism in Europe and the mass slaughters orchestrated by Stalin and Hitler. But in the post-9/11 era of perpetual war, we sense a growing possibility that tyranny or anarchy might soon be unleashed again at an equivalent level. And not even the “worst” know how this revelation will play out. “The Second Coming” leaves us suspended in anxious (yet thrillingly hopeful) uncertainty. Apocalyptic fantasies, after all, are crude hopes for rebirth through barbaric destruction.

Yeats’ luminous language paints the human world in its arresting beauty and jarring turmoil. Yeats helps us know ourselves more deeply and remember that we are alive in a time of great error, tension, and possibility, what he termed “the filthy modern tide.” His poems provide examples of powerful, precise language that chronicles the vicissitudes of the modern heart blasted by the winds of history.

The Second Coming! Hardly are those words out

When a vast image out of Spiritus Mundi

Troubles my sight: somewhere in the sands of the desert

A shape with lion body and the head of a man,

A gaze blank and pitiless as the sun,

Is moving its slow thighs, while all about it

Reel shadows of the indignant desert birds.

The darkness drops again; but now I know

That twenty centuries of stony sleep

were vexed to nightmare by a rocking cradle,

And what rough beast, its hour come round at last,

Slouches towards Bethlehem to be born?

Beware! Something is happening here and we don’t know what it is. The poet drives himself into a state of dread thinking about what a new divine intervention might look like. A disturbing image from the soul of the world “troubles his sight.” He sees something approaching in the distance–a sphinx from the sands of the desert–and it doesn’t look friendly. Phrases like “a gaze blank and pitiless as the sun” and “shadows of the indignant desert birds” create an ambience of overwhelming, inhuman doom. The rough beast in the distance slouches to be born in Bethlehem, birthplace of Jesus.

For Yeats, the Second Coming was not a literal return of Jesus Christ, but the arrival of savage, atavistic forces: the death and birth pangs of an old epoch making way for the new. Yeats hoped this tumultuous transition would be a precursor to a new, revivified world, but he suspected that the rough beast being born would be more terrifying anti-Christ than gentle Jesus. The rough beast of the new revelation hates gentleness, imagination, and community and feasts upon violence, fear, and alienation. If you ever drive on the highway, watch the news, or walk down the street and look in people’s eyes you may have already seen its shadow.

Yeats the Wandering Star

In order to understand Yeats and his visionary power with language, you must first know of his early life and background. Yeats grew up in the Sligo countryside of northwestern Ireland in the late 19th century. Even though he came from an Anglo-Irish, Protestant family, he was first known in Ireland for his important contributions to the Celtic literary revival. Along with his distinguished patron Lady Gregory, he gathered forgotten Irish myths and tales, incorporated their characters and themes into his stories and poems, and encouraged other artists such as playwright J.M. Synge to do the same.

Yeats thought himself to be one of the last of the classical Romantics; he celebrated the power of imagination to help people see and empathize deeply, he recognized the dangers of abstract reasoning divorced from imagination and the natural world, and he sought a kind of lost knowledge not taught in schools or churches. Yeats rejected realistic, imitative art. He believed that only art that recognized and celebrated the panpsychic power of imagination, myth, and symbol could reveal the deeper truths and intuitive meanings underlying everyday experience.

In his poem “Who Goes with Fergus?” Yeats invokes the ancient king of Irish legend who abandoned his high office and its grating, relentless demands to head to the woods and learn the mysterious “dreaming wisdom” of the Druid priests.

For Fergus rules the brazen cars,

And rules the shadows of the wood,

And the white breast of the dim sea

And all dishevelled wandering stars.

Fergus is a hero of the imagination who leaves the everyday human world to revel in the mysteries of nature and spirit. The “shadows of the wood” and “the white breast of the dim sea” represent primeval knowledge and beauty that can only be glimpsed through experiences of wilderness solitude, trance, magic, and meditation.

Full of fantasies of a better world, the young Yeats struggled to accept regular life on earth and sought desperately to find a way into other dimensions of space and time. In “The Stolen Child,” he portrays an alluring, otherworldly kingdom that calls us from the frustrations of everyday life to the eerie phantasm of the faery dance.

Where the wave of moonlight glosses

The dim grey sands with light,

Far off by furthest Rosses

We foot it all the night,

Weaving olden dances,

Mingling hands and mingling glances

Till the moon has taken flight;

To and fro we leap

And chase the frothy bubbles,

While the world is full of troubles and is anxious in its sleep

Come away, O human child!

To the waters and the wild

With a faery, hand in hand,

For the world’s more full of weeping than you can understand.

The landscape is lit up with moonlight, under which things dark and hidden become visible. The powerful faeries (creatures who in Celtic tradition are emphatically not small, cute, or winged) call the poet to “the waters and the wild,” the fluid, frothy, and sometimes freaky realm of visionary trance and imagination.

Yeats could have continued writing poems of luscious Romantic sorrow and yearning as he did as a young man for the remainder of his life and achieved wide recognition in Ireland. But he chose something more. He challenged himself to test the limits of language and consciousness. He hoped that the images he conjured would arouse trance-like states of mystical awareness in the reader and deep insight into the world around them. Yeats, dishevelled wandering star that he was, continued to develop his poetic style and thought until the time of his death. He labored heroically to combine his idealistic, escapist perspective with an unflinching look at life in the world with all its messy particulars and wrenching agonies, what he dubbed “the fury and the mire of human veins.”

Most great writers either excel in the realm of the imaginative or of the realistic. A select few, like Shakespeare, Pablo Neruda, Emily Dickinson, and Yeats, deftly fuse both spheres. Yeats performed a sort of linguistic and philosophical alchemy to mix the imaginary and the real in a way that created something altogether new. Yeats’ ability to bring together the world of intensified, glittering poetic inspiration with the quotidian world of stumbling struggle set him apart from all his contemporaries and almost all other poets to ever write in English. By the end of his life, Yeats was writing multidimensional poems such as “Easter, 1916” and “Lapis Lazuli,” which combine visionary perception and realistic detail. For his achievements, he received the 1923 Nobel Prize for Literature and T.S. Eliot’s unofficial designation as poet of the age.

Yeats the Mystic

Yeats was engaged in numerous esoteric practices: he performed ceremonial magic, studied Hindu philosophy and meditation, investigated Japanese Noh drama, and as a young man interviewed rural Irish elders about their experiences in the uncanny realm of faery. Yeats attended séances to communicate with the dead and married a woman who claimed she could transcribe mantic teachings from discarnate teachers. In “Byzantium,” Yeats describes the cryptic realm of spirits for which he so fervently searched.

Before me floats an image, man or shade,

Shade more than man, more image than a shade;

For Hades’ bobbin bound in mummy-cloth

May unwind the winding path

The world of spirits is obscure; the speaker doesn’t know if he is beholding “an image, man, or shade.” Eventually he decides that the apparition is ultimately composed of an image. Unraveling this image reveals still more mysterious pathways into the spectral realm of Hades, the invisible foundation of the daylit world.

The mystical and invisible dimensions of life and consciousness fascinated Yeats. He was not convinced by the teachings of dogmatic Christianity, nor was he satisfied by his father’s insistently skeptical outlook on matters spiritual. Rejecting these two contraries, Yeats pursued his spiritual yearnings in the ancient yet experimental Western esoteric tradition. In his poem “To the Rose upon the Rood of Time,” Yeats expresses his bold intention.

But seek alone to hear the strange things said

By God to the bright hearts of those long dead,

And learn to chaunt a tongue men do not know.

Yeats was not content to merely read about or profess belief in a divine reality. He wanted nothing less than gnosis, knowledge and insight of this hyperreal dimension culled from direct, trance-like experiences of supersensory, subtle realms of consciousness.

This pursuit of unorthodox–some would say bizarre or dangerous–forms of knowledge not only piqued Yeats’ curiosity about the nature of life and the depths of the mind, but also provided him with an abundance of potent ideas and images for many of his poems. “Byzantium” evokes a world of phantasmagoric rapture and revelation.

Dying into a dance,

An agony of trance,

An agony of flame that cannot singe a sleeve.

Astraddle on the dolphin’s mire and blood,

Spirit after spirit! The smithies break the flood,

The golden smithies of the Emperor!

Marbles of the dancing floor

Break bitter furies of complexity,

Those images that yet

Fresh images beget,

That dolphin-torn, that gong-tormented sea.

Yeats and The Critics

Some critics, such as Yeats’ contemporaries W.H. Auden and George Orwell, considered his preternatural inclinations to be peripheral to his literary enterprises, not to mention outrageous and silly. They recognized Yeats’ rare gift with language, but openly mocked his metaphysical yearnings. “How on earth, we wonder, could a man of Yeats’ gifts take some nonsense seriously?” asked Auden. “How could Yeats, with his great aesthetic appreciation of aristocracy, ancestral houses, ceremonial tradition, take up something so essentially lower middle-class–or should I say Southern Californian… Mediums, spells, the Mysterious Orient–how embarrassing.”

Orwell, who wrote a scathing essay outlining what he considered Yeats’ reactionary political tendencies, was only slightly more forgiving: “One has not, perhaps, the right to laugh at Yeats for his mystical beliefs–for I believe it could be shown that some degree of belief in magic is almost universal–but neither ought one to write such things off as mere unimportant eccentricities.”

But a generation later Kathleen Raine, a scholar and poet firmly embedded in the Romantic tradition, insisted that Yeats’ unconventional quest to glimpse the living mysteries of life was central to his poetic power and achievements. Raine reminds us that the esoteric ideas that captivated Yeats, while not dominant in our culture, have a long, storied history of their own stretching back to ancient Greece and the Renaissance, two creative pinnacles of Western Civilization. In addition, seminal modern thinkers in the realm of mythology and psychology such as Norman O. Brown, C.G. Jung, and Mircea Eliade have taken seriously notions about magic, spirits, and imagination almost identical to those held by Yeats. All three championed important forms of knowledge that stretch back to the origins of humanity. In the poem “Fragments,” Yeats descends into these primordial roots of the gnosis he so desired.

Where got I that truth?

Out of a medium’s mouth,

Out of nothing it came,

Out of the forest loam,

Out of dark night where lay

The crowns of Nineveh.

The Poet summons a non-rational mode of perception that existed long before civilization began in ancient Mesopotamia. Yeats was in search of dynamic symbols and images with the power to blow apart the intellect’s ability to comprehend or analyze them. This ability to express evocative images from the depths of psyche such as “that dolphin-torn, that gong-tormented sea” is central to Yeats’ greatness as a writer.

Yeats believed that his pursuit of supersensory knowledge gained through meditation, magic, and trance, even if considered odd or unorthodox by many, was essential for his life task of creating meaningful, prophetic poetry. Über-critic Harold Bloom notes, “Yeats knew himself to be the heir of a great tradition in poetry, of the visionaries who have sought to make a more human man, to resolve all the sunderings of consciousness through the agency of the imagination.”

Yeats the Avatar of Culture and Imagination

Culture is partly a conversation with the past. We can read newspapers or watch the latest movies, but without the opportunity to reflect and test our ideas and experiences against the backdrop of history we remain psychologically and politically naïve and our conversations stay on the surface. And culture, of course, does not mean just what happens in a university or at the art museum. Culture in its essence means vigorous engagement with the great questions and discussions of human life.

Throughout a lifetime of art and study, Yeats maintained lively intellectual interchange with Plato and the Greeks, Shakespeare, William Blake, Hindu spiritual traditions, philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche, and the ancient Celts. For Yeats, the idea of conversation with the past was not a mere metaphor. He continually read, mulled over, and argued in his mind with many thinkers who came before him. He viewed the pursuit of truth as a living process and found inspiration to create something significant and new by engaging in a virtual symposium spanning space and time.

For Yeats, the soul, the imagination, and possibilities for cultural renewal were one in the same. And for him, there was no better way to advance this great conversation and find vision for the future than through the study of philosophy, magic, and mysticism. Although no political progressive, his profound insight into the nature of consciousness and imagination blazed the way for a 20th-century rebirth of holistic spiritual values that Beat poet and ecological activist Gary Snyder considers a “surfacing of the Great Subculture which goes back as far perhaps as the late Paleolithic.” Yeats, convinced that modern Westerners had lost touch with certain essential, archaic psycho-spiritual experiences, wrote poems that hearkened a time of stone-age paganism, fifty-foot high fires, yowling giant beavers, and ecstatic rituals in honor of antlered, dancing gods.

Yeats was greatly influenced by early nineteenth-century artist William Blake, who emphasized the supreme importance of visionary imagination. For Blake and for Yeats, imagination is not merely the province of children. Imagination is the archaic, ineluctable power of the psyche and consciousness itself to form not just art but cities, architecture, laws, religions, and relationships. Before you have sex or paint a mountain landscape or start an accounting business, you have an intuition or vision that starts the whole process going.

To this way of thinking, imagination is at the root of all human thought, action, and endeavor. Along with psychologist C.G. Jung, Yeats believed in the primacy of consciousness, that everything we do, think, feel, create, and are is filtered through the lens of consciousness and the psyche. Yeats’ explorations of the esoteric helped give him deep access to this primary field of consciousness and imagination.

The mystical gospel according to Yeats:

1. That the borders of our mind are ever shifting, and that many minds can flow into one another, as it were, and create or reveal a single mind, a single energy.

2. That the borders of our memories are as shifting, and that our memories are part of one great memory, the memory of Nature herself.

3. That this great mind and great memory can be evoked by symbols.

The above tenets, outlined in Yeats’ 1901 essay “Magic,” greatly informed his artistic pursuits. Yeats was intrigued by phenomena like telepathy and magical cures that lay outside the purview of science. Throughout much of his life he engaged in various practices designed to connect with the world of spirits and the great memory of “Nature herself.” Magic to Yeats did not refer to sleight-of-hand tricks like pulling a rabbit out from a hat, but rather to attempts to gain access to non-ordinary dimensions of life through the use of symbols, rituals, incantations, and creative visualizations. Yeats believed there was a direct connection between his magical and artistic endeavors in that both activities draw upon the power of symbols and imagination. “I cannot now think symbols less than the greatest of all powers, whether they are used consciously by the masters of magic, or half-consciously by their successors, the poet, the musician, the artist,” he proclaimed.

As a young man Yeats became interested in the Order of the Golden Dawn, a group dedicated to helping its members practice Western esoteric magic and realize spiritual truths in a direct, experiential way not available in more orthodox traditions. The OGD drew inspiration from various spiritual traditions, but gave special emphasis to the mystical Jewish tradition of the Kabala. In 1884 the Scotsman S. Liddell Mathers (who changed his name to MacGregor Mathers to reflect his penchant for things Celtic) founded the order with the intent to renew certain secret and ancient spiritual traditions. Yeats remarked, “It was through him [Mathers] mainly that I began certain studies and experiences that were to convince me that images dwell up before the mind’s eye from a deeper source than conscious or subconscious memory.”

Yeats was eager to explore non-ordinary experiences and states of mind because they gave him access to an ocean of living symbols and revelations previously unseen that would illuminate human conflicts and aspirations. As a poet who aspired to express the highest registers of intensity and truth about human life, Yeats sought to find and convey numinous images that sliced through the surface news of the day to a realm of naked, pulsating revelation.

According to Jung, this mysterious, spiritual dimension of life Yeats sought access to is the Collective Unconscious, the part of the unconscious mind shared by all people, past, present, and future. The Collective Unconscious is a sort of cosmic Internet that contains the myths, dreams, symbols, hopes, terrors, and life patterns of all people from throughout space and time.

Yeats, like Jung, believed that all the memories and potentialities of the human race from the primeval past through the present are contained in a matrix of transcendental symbols and images. Yeats called this dimension spiritus mundi, or the spirit of the world. He hoped to connect with the sublime, imagistic depths of this collective soul through his sundry esoteric practices and to relay what he found there in his carefully wrought poems.

Yeats the Prophet of a New Age

Since our culture’s main criteria for truth is a scientific, empirical true or false, we leave little room for the truth of stories that the ancient Greeks called mythos. To the standard, literalistic way of thinking, either something is true or it isn’t. This form of black-or-white thinking is useful in many technical realms of life, such as building bridges or conducting surgery, but deadly to spirituality, art, and the realm of relationship. People forget that many things, such as a religious story, a novel, a passionate feeling, or a mystical experience, can be real and meaningful without being literally true or measurable. Entering into the realms of mystical insight and visionary poetry requires a move into this symbolic yet real world of mythos. Yeats insisted that visionary, mythic knowledge is not less real than scientific forms of knowing, and can help us apprehend truths about life that science cannot.

Along with Blake, Yeats decried the materialistic values that permeate modern civilization and prevent us from directly experiencing the reality of mythos and direct spiritual revelation. Materialism in this context refers to the belief that reality is nothing more than what we can perceive externally with our five senses and discern through rational thinking and science. Philosophic materialism views consciousness and the soul as a pure product of chemical reactions in the brain, rather than an infinite, holy web in which we live, dream, and die, what Yeats describes as “Heaven blazing into the head.”

In his book Re-Visioning Psychology, James Hillman challenges the claims of literalism and materialism and posits an intermediary zone between the pure, abstract world of spirit and concepts and the mundane, manifest level of human material existence. This in-between realm–known as the imaginal or daimonic realm–is the home of imagination, angels, demons, spirits, fantasy, planetary gods, elements, fairies, and the dead. Some regard these presences as mere poetic metaphor while others consider them discrete entities in and of themselves. Hillman and Yeats both understood that this imaginal realm couldn’t be understood or defined with literal thinking or rational analysis.

Yeats immersed himself in this imaginal realm through experiences of visionary trance, yet these sorts of experiences are not only possible for a mystic or master poet. Yeats did not provide a specific prescription to follow in order to enter these visionary states of mind. Yet his life and work led the way for people to consider how they might best enter into more imaginative and cultured perspectives on life and the soul. He was willing to take risks and even appear a little foolish for the sake of finding a more vibrant and transcendent experience of life, and for that he stands as a worthy model for those who have strong, eclectic spiritual yearnings yet do not feel welcome or comfortable in mainstream religious traditions.

In our profane age of accelerated, mind-numbing consumer and media overload, Yeats’ intrepid example inspires us to seek a more animated, complete worldview rooted in direct experience and study. Humans live in an increasingly disconnected world: disconnected from the natural world, from each other, from meaningful spirituality and dialogue, and immersed in a virtual world of television, electronic blips, and purely human concerns. Despite changes in technology and outer appearances, we still have the same psyches as our ancestors. A deep explorer of the soul like Yeats directs our attention to important, perennial patterns and images, reminding us of key forms of knowledge that lead to connection and vitality rather than alienation and fanaticism.

Although some of Yeats’ ideas seemed and still seem strange to many, he felt that many in modern times had a narrow view of what constitutes consciousness and reality. He also felt that the time was coming when more people would recognize the reality and power of the mystical and imaginal. When he wrote “The Secret Rose,” he foresaw a time when the soul–represented here as a hidden rose–would revolt against the domination of the literalistic intellect.

I, too, await

The hour of thy great wind of love and hate

When shall the stars be blown about the sky,

Like the sparks blown out of a smithy, and die?

Surely thine hour has come, thy great wind blows,

Far-off, most secret, and inviolate rose?

Yeats imagines that the beautiful, shocking truths of the secret rose will be revealed only after great tumult. Some kind of star must flame out spectacularly before we recognize what is most essential in our lives.

Even though he entertained dramatic possibilities about the future of human life and avidly explored the arcane world of magic and mysticism, Yeats always maintained some level of skepticism throughout his life about the ultimate validity of his esoteric theories. He seriously considered that the meanings he so ardently pursued might be mere fiction. His skepticism somehow makes his views more convincing, though. What could be more human than to experience uncertainty and doubt in the face of an awe-inspiring, multi-faceted universe?

As an older man, Yeats lamented the loss of his bodily power, and wondered in “Sailing To Byzantium” what, if anything, outlasts the decay of the human physical form. His answer, the result of all his spiritual and artistic wandering, restates his faith in the power of visionary art to touch the eternal within us.

An aged man is but a paltry thing

A tattered coat upon a stick, unless

Soul clap its hands and sing, and louder sing

For every tatter in its mortal dress,

Nor is there singing school but studying

Monuments of its own magnificence

We live in desacralized times: political leaders blatantly manipulate language, frightened citizens cling desperately to narrow systems of belief, and people have more communication technology yet feel more isolated than ever before. Yeats’ writings help illuminate our confusing inner experiences in this age of historical and psychological upheaval. He points us to an ancient worldview in which soul and imagination are primary, forging a vital middle ground between consumer materialism and rigid fundamentalism. Still relevant nearly seventy years after his death, Yeats conveys a timely, humanizing vision that challenges us to explore the mysterious spiritual foundations of our lives and create a culture receptive to beauty and a meaningful sense of the sacred.