Santa Claus might be the jolly, bearded, gift-giving symbol of Christmas, but in his original suit, Santa might have been an Amanita muscaria mushroom shaman. Santa Shaman? Shaman Claus?

For many of us, Santa was a seminal figure in our childhoods. As our parents tucked us into our beds on Christmas Eve, we couldn’t wait to wake up the next morning. There were some of us, perhaps, who tried to stay awake in hopes of catching Santa in his red-and-white suit, but our fatigue usually won in the end.

In what seemed like a split-second, our eyes opened to Christmas morning. We bolted to the Christmas tree in our pajamas to see if Santa had indeed paid us a visit. New presents were left under the tree. The snacks that we left for Santa and his reindeer—milk and cookies and carrots—had been eaten. Santa was here!

However, the revelation that Santa Claus was never there, never real, caused most of us, if not all, to dismiss the whole story as a fairytale. But what if Santa was real? What if the real Santa Claus was a shaman (with reindeer) who came down the chimney with a bag of mushrooms?

In the heart of winter, as cities worldwide twinkle with festive lights and children eagerly anticipate the arrival of Santa Claus, few are aware of the ancient, mystical origins of these beloved traditions. Deeply rooted in shamanistic rituals involving the Amanita muscaria mushroom, the story of Santa and the customs we cherish today weave a rich tapestry of history, spirituality, and cultural interconnection.

It’s time to put the trippy back in Christmas.

Santa Claus or Shaman Claus?

Our modern perception of Santa Claus, a cheerful, gift-bearing figure in a red-and-white suit, may find its origins not in the North Pole but in the frigid, snow-laden landscapes of ancient Siberia. Here, a shamanistic culture thrived, deeply connected with nature and the spirit world.

These shamans, dressed in colors mirroring the Amanita muscaria mushroom, were not only healers and spiritual leaders but also harbingers of joy and communal unity during the darkest days of winter.

The Evenki of Siberia

In this wintry wonderland, if you go searching for Santa, you may not find him or his Elvin factory–but you will find groups of indigenous people native to what we know as Siberia. Among these cultures are the northern Tungusic people, known as the Evenki. The Evenki were predominantly hunter-gatherers as well as reindeer herders. Their survival largely depended upon the health and vitality of their domesticated reindeer.

The reindeer provided the Evenki and other northern tribes with everything from clothing, housing material, wares and tools from the bones and antlers, transportation (yes, they ride reindeer!), milk, as well as cultural and religious inspiration.

The Evenki were also a shamanic culture. The word “shaman” actually has its roots in the Tungus word saman, which means “one who knows or knows the spirits.” Many of the classic shamanic characteristics that would later be reflected in cultures all over the world were originally documented by Russian and European explorers while observing the Tungus and related people’s religious life.

This includes the three-world system, the shamanic journey or soul flight, the use of altered states of consciousness, animistic belief in spirit, and so forth.

Amanita Muscaria Santa

A significant aspect of the shamanism practiced in this part of the world during that time was linked to Amanita muscaria, also known as the Fly Agaric mushroom. This mushroom is more widely accepted in the modern world as the Alice in Wonderland mushroom. It was held very sacred by these ancient people and was used by the shamans and others for ceremonial and spiritual purposes.

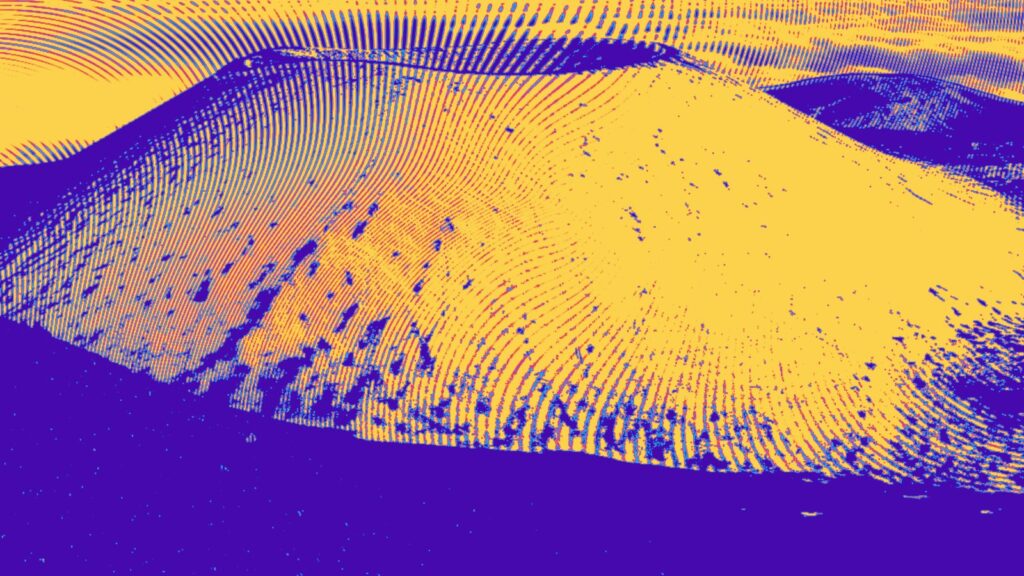

Amanitas—as you can tell by the pictures—range from brightly red and white to golden orange and yellow. They only grow beneath certain types of evergreen trees. They form a symbiotic relationship with the roots of the tree, the exchange of which allows them to grow. One of the reported ancient beliefs was that the mushroom was actually the fruit of the tree. Due to the lack of seed, it is also commonly held that Fly Agaric was divine—a kind of virginally birthed sacred plant.

Although intensely psychoactive due to the presence of muscimol, Amanitas are also toxic. One way to reduce the toxicity and increase the psychoactive potency was to simply dry them. When collecting the mushrooms, people would pick a bunch of them under the evergreen trees and lay them out along the branches while continuing to pick the mushrooms beneath other trees.

The result was something that looked very reminiscent of a modern Christmas tree: evergreen trees whose branches are dotted with bright red, roundish “decorations”—in this case, the sacred mushrooms. At the end of the session, the shaman or harvester would go around to each of their mushroom stashes and put them all in one large sack. Remind you of anything?

Not only this, as the story of the tradition goes, the shaman would then, carrying this large sack, visit the homes of his or her people and deliver the mushrooms to them. They would then continue the drying process by hanging them in a sock near the fire.

The Shaman, Reindeer, Mushroom Connection

We know the Evenki people relied upon their relationship with the reindeer. But how did this connection interplay with the Amanita muscaria mushrooms? Well, the reindeer were in on it!

Reindeer Took the First Bite

One way to reduce the toxicity of sacred mushrooms is through human filtration. Once passed through the body, the toxic elements are apparently filtered by the liver and the resultant urine that comes out contains the still intact psychoactive elements. So, they drank the filtered urine. But that’s only half the story. Somewhere in the mythic origins of this practice is the reindeer.

Because naturally the reindeer also love these mushrooms. They dig through the snow to eat them, and they also drink their own urine afterward. Perhaps, long ago, one of the first shamans witnessed the reindeer’s love affair with this peculiar mushroom—as well as its propensity for eating its own freshly yellowed snow—and saw how peculiarly it behaved as the mushrooms took hold.

The curiosity (indeed a hallmark characteristic of a shaman) couldn’t be contained, and the shaman did what he had to do: he first ate some of the yellow snow himself…and without a doubt realized the profound wisdom and magic not only in the mushroom but in the reindeer.

The Flight of Santa Shaman

The connection between the reindeer, the mushroom, and the shamanism is apparent. A very common vision that one has while under the influence of Fly Agaric is precisely that: flying. Massive distortions of time and space occur, affecting scale in dramatic ways. Not only do you observe yourself flying, but also other things…like reindeer. It is not that difficult to connect the dots here.

Shamanic people are deeply invested in their environment. They learn the magical and mystical properties of the natural world and often assign a great deal of importance and sacredness to the bearers of that magic.

For some of these ancient Siberian people, this power was charioted by the reindeer and the sacred mushroom. That the reindeer should have the ability to fly is evident not only in the vision or their clearly altered state once intoxicated but also in the wisdom they offered to the shamans by eating the mushroom in the first place, and for guiding them to do so just the same.

It wasn’t only the reindeer who could fly, but the shamans also took flight. As mentioned, the shamanic journey, or soul flight, is a keystone in shamanic practice, especially in ancient Siberian culture. In order to interact with the spirits, the shaman had to be able to leave this world and enter theirs. This was accomplished by projecting his or her spirit from the physical and into the immaterial.

They either needed the power to do this on their own or used a spirit helper to take them. It is very common for shamans to develop relationships with birds, naturally, as they have the power to fly. But here, in the frigid tundra much like the North Pole, what better animal to use than the magical, flying reindeer?

World Tree and the North Star

There is one other component to the shaman’s flight that corresponds to our Christmas exploration, and this has to do with how they got to the other worlds. The shamanic cosmology often consists of three worlds: the Lower, Middle, and Upper Worlds. Connecting the three worlds is a cosmic axis, which is also commonly known as the World Tree. The World Tree served as a bridge or portal that allowed a shaman and spirits to move between the three worlds.

It was the gateway as well as the highway. In ancient Siberia, the same tree that also bore fruit to the Amanitas was also a symbol for the world tree. The Evenki and other indigenous groups lived in roundish teepee-like structures called yurts. Sometimes they would place a pine tree in their yurts for ceremonial purposes. This symbolized the World Tree, and they would harness its symbolic power to propel their spirit up and out of the yurt—through the smoke hole, i.e. the chimney.

Once the journey was complete, they would return through the smoke-hole/chimney with the gifts from the spirit world. They also believed that the North Star was the very top of the Upper World, and because the World Tree was an axis that connected the entire cosmology, the North Star sat upon the very top of the World Tree—which is where the tradition of placing a star at the top of the tree comes from.

Ritual of Gift Giving

One of the final elements of the Christmas tradition that we know today is the whole concept of gifting. What are we celebrating? When you begin to unravel the experience of the shaman’s flight and dance with Amanita, you enter a world that is deeply sacred. These shamanic cultures were intimately interwoven with their environments through the reindeer and the mushroom in a way that honored and celebrated the mysteries and magic that life and experience brought to the people. The shaman’s journey and return were ultra-important to the survival of the whole community.

What they brought back with them was often a matter of life and death. Time and again, the shaman and the people would learn knowledge and wisdom through these experiences. They deemed these experiences not only sacred but divine, deriving insights directly from the sacred plants, their journeys, and the spirits with whom they interacted.

This was a kind of lifeblood for their way of being. This was the gift. The celebration was actually a kind of celebration of life, continued survival, and renewal. It was an honoring of the spirits, animals, plants, and natural world that gave them the gift of life and knowledge of life.

Birth of the Sun (not Son)

This brings us to the grand finale, the big present hidden way back under the tree: Jesus Christ, and the timing of his arrival on Earth. Concurrent with Jesus’ storied birth is a yearly alignment with the sun. On the December 21st winter solstice, the sun reaches its furthest southern point, bringing the northern hemisphere its longest night.

For three days, the sun remains apparently unmoving. On the morning of the 25th, the sun begins its northern ascent once again. This can be looked at as the birth of the sun, which has spent the winter traveling in the lower world, or the world of darkness.

When the sun begins to climb once again, it is a time to celebrate the light—literally the return of the light, the source of life on Earth, and ultimately the assurance of the coming summer, which also means the survival of the natural world, the animals, the plants, the people and their way of life. Hence, life and the people are saved.

To indigenous peoples who depended on the seasons’ movement and bounty—and especially for the far northern peoples of ancient Siberia—this was a monumental time. The sacred Amanita, with its red, golden, and orange coloring as well as its capacity to offer direct experience and connection with divinity, was also regarded as a symbol for the Sun and its life-giving and saving properties.

The Sun—or the Son—is the savior, born on the 25th of December as the bringer of light, harbinger, and liberator of life on Earth. This is the gift and the meaning of the holiday we know as Christ-Mass.

From Shamanic Rituals to Modern Traditions

The journey from the ancient shamanic rituals of the Evenki to the contemporary celebration of Christmas is a fascinating one. Over centuries, these practices evolved, intertwining with various cultural beliefs and customs. The figure of Santa Claus, as we know him today, is a composite of these ancient traditions, Christian influences, and modern storytelling.

In this light, the traditions of Christmas become more than mere customs; they are a tribute to our shared human heritage, a celebration of life’s magic and mysteries, and a reminder of the enduring power of joy, generosity, and the human spirit.

As we gather around our Christmas trees and exchange gifts, let us remember the ancient shamans who, in their red-and-white garb, brought light and warmth to the coldest nights and, in doing so, laid the foundations for one of the world’s most beloved holidays.