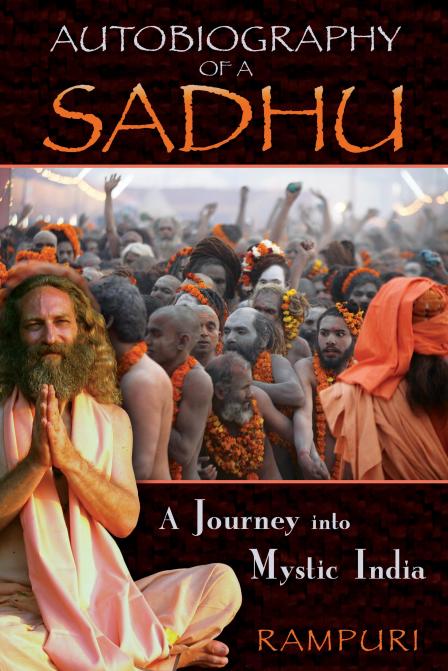

The following article is excerpted from Autobiography of a Sadhu: A Journey into Mystic India (available from Inner Traditions).

Becoming Rampuri

If I were a rishi-sage, a suta-bard, or some other ancient hearer or teller of tales, or even an overzealous devotee, I might say that when Hari Puri Baba was born, the gods and the goddesses rained fragrant flowers from heaven, cows tripled their flow of milk for a month, and for once, there was peace on Earth. But, no, I won't say that. I will give you only the facts. I will tell you that he was a far from ordinary child. He came from a Brahmin family, the royal astrologers to the kings of Mandi, in what is now Himachal Pradesh. An old traditional family, it passed the treasure trove of the knowledge of past and future as well as the timing and suitability of important events from father to son from at least the time of the Rishi Bhrigu, millennia ago. Kings from the four directions, yogis, scholars, and even great astrologers would come for consultation for the predictions and advice were infallible.

Hari Puri Baba's mother fainted when informed by her husband that their firstborn son would become a great sannyasi. Anything but that. She knew her husband had the power to counteract certain influences that could be interpreted from the heavens, and begged him to do something. Not that Hari Puri Baba's father wanted his son to become a sadhu, but he knew a baba when he saw one.

On the day of a lunar eclipse, when the world hides in fear inside their homes, Sandhya Puri Baba, the great and famous Siddha, a wizard who had accomplished superhuman yogic powers, came for consultation with Hari Puri Baba's father. On that day ten-year-old Hari Puri Baba's world changed. Enchanted by the baba, and always hardheaded, the boy decided to follow Sandhya Puri Baba. He didn't want to become an astrologer, telling other people what to do. He wanted to be free as the wind, wandering here and there, learning and practicing siddhis like Sandhya Puri Maharaj. His mother's tears couldn't stop him (his mother did, however, give him both permission and blessings to leave), and his father, impressed by Sandhya Puri Baba, reasoned that if his son were to be a sadhu, then at least he would be the disciple of a great saint.

Even by the time he left home, however, he had already achieved mastery over several intellectual/spiritual traditions in Sanskrit (including astrology), and was considered somewhat of a prodigy in language and mantra.

As a disciple, he trained under Sandhya Puri, wandering barefoot "hither and thither," as he would later say, throughout the Himalayas, in Kashmir, Punjab, Nepal, Yarkhand, Tibet, and other parts of what is now China. Sandhya Puri would take him for darshan, the auspicious seeing and meeting of other siddhas who lived and practiced austerities in high Himalayan caves. He would leave his young disciple there for a year at a time to perform seva, auspicious service, to the great ones.

This is the guru shishya parampara, the path of discipleship: Perform service to the guru, please him, and if you are lucky, then perhaps he will give you his blessing, an ashirvad. Let the ashirvad grow, and over decades a transmission takes place in which the disciple absorbs the Tradition as well as the personality of the guru. Please him a lot, and you may compel him to do your bidding, as humans have compelled gods, by pleasing them a lot, since story took birth.

Over the years, Hari Puri Baba obtained a number of siddhis. I knew him for only a short time and cannot vouch for whatever powers he might (or might not) have had, but I can attest to his great knowledge of language. Sanskrit and Indian languages, even Tamil, Telegu, and Maliyalam are one thing. His sophisticated "foreign-returned" sounding English is not rare in a country like India. The European languages-French, Italian, and Spanish-raised my eyebrows a little, even more when I heard him speak German, which he had picked up in less than a day. But when I saw him in conversation with crows, my order of things became disorderly. He spoke Ka Bhasha (crow language), the language of birds.

Until recently I never met another Naga Sannyasi of Juna Akhara, the Old Order, who spoke any English. It was a boon for me that my sharp transition into Hindi would be cushioned by the fact that my guru spoke my mother tongue.

In 1959, Hari Puri Baba visited the Bhrigu Shastri, a great astrologer, in Hosharpur, Punjab, who possessed the Bhrigu Shastra, a text composed thousands of years ago by the Rishi Bhrigu, his ancestor. The Bhrigu Shastri also has a highly guarded section of that ancient text, which contains horoscopes for those who would approach his lineage for thousands of years to come. He is able to find the horoscope for anyone who approaches him. He simply notes down the precise moment the client crosses the threshold of his simple house, makes a few calculations, and then starts poring through his palm leaf manuscripts, looking for that particular individual in his nonlinear chronology of horoscopes. Hari Puri Baba stayed with the Shastri for several weeks while they went through Baba Ji's life, as well as his past lives.

Baba Ji learned that he would have only three disciples. One would perish in a fire, one would lose his powers and eventually be murdered, and the third would be a foreigner. I asked Hari Puri Baba Ji several times what would happen to the foreigner, but he never told me. All he would say was that he knew the exact moment I would cross the threshold of his ashram at Amloda Kund in Rajasthan ten years later.

I was blissfully unaware of all this as I sat among naked yogis in what could have easily been the twelfth century. I was also unaware that I had already been included in the story of Hari Puri Baba. All I knew at the time was that I was about to be initiated into the Tradition of Knowledge-whatever that meant.

When the barber arrived, I knew I was in trouble. The babas all had long hair, much longer than mine. I decided that my hair was far too precious to give up without being certain that I could trust Hari Puri Baba. Maybe all these babas were just playing around with me?

"I can't go through with this, Swami Ji," I said. "I don't want my head shaved."

"You do what you like," said Hari Puri Baba, flashing his disarming smile. "But how will you become like a baby in order to obtain new knowledge? I should have him shave all your hair, down there too, not just your head and face. How will the three worlds know you are my disciple, Rampuri, if you don't follow the Path?"

I asked him what this "rampuri" business was all about. He assumed that I understood much more than I did, including that I had acquired a new name. I had been in Amloda Kund only half a day and had already lost my own name. Anyone becoming a sannyasi is given a new name, a name for entering into a new world. It was then that I discovered that Hari Puri Baba had named me Ram Puri.

He explained to me why he had given me this name. Puri is like a last name, passed down from guru to disciple in the tradition of the sannyasi. In the fifth century BC, Adi Shankara formalized preexisting groupings of renunciates, shamans, and yogis, into an order that became known as the Order of the Ten Names, the members of which became known as Sannyasis. One of those names was Puri, and it has been passed down, guru to disciple to the present day. Ram is a common Indian name taken from the god Vishnu's incarnation as the prince from Ayodhya who rescued his princess from the demon Ravana. The name Ram was chosen by Hari Puri Baba largely on the basis of an astrological calculation. Rampuri also means a distinctive knife-a switchblade-that comes from the town of Rampur, after which it was named.

Adi Shankara, who many believe was an incarnation of Shiva, was perhaps India's greatest thinker and reformer. He renounced the world at the age of eight, having mastered the sacred books of the Vedas, and in twenty years he not only composed many of India's greatest philosophical and devotional texts, reformed the religion of the Brahmins, established India's four great centers of learning, and formed the Order of Sannyasis, but taught a way of knowing oneself that is still widely practiced around the world-Advaita Vedanta. He vanished from the world (literally) at the age of twenty-eight.

A small troop of children followed me to a shaded area in the rocks where the barber would practice his art on my scalp as I considered my options. Should I make a break for it and run? How far was it to the main road? How could I escape?

But, hold on. I wasn't a condemned man walking slowly toward the gallows clinging to his one hopeless fantasy of freedom. It was only a haircut. Drop your attachments, I said to myself.

The barber handed me a small mirror in a rusty frame so that I could watch the clumps of hair fall from my head. The children giggled as they watched him shave my beard and then my scalp with his open blade. He smiled as I felt my smooth cranium, with one short tuft of hair remaining on the top back of my head. "Guru Ji," he said, giving it a slight tug.

Hari Puri Baba had assembled four other sadhus in the ashram's puja room. The room was dark, and it took a few moments for my eyes to adjust. The walls were covered with rotting photos of awe-inspiring sadhus and posters of Indian gods and goddesses. Straw mats were spread on the floor, and a few sticks of incense burned on an altar housing several deities and a few small Shiva lingas. Amar Puri Baba placed a bundle in front of Hari Puri Baba consisting of an ochre dhoti, a coconut, a rudraksha seed strung on the janeu string of the twice born, and two strips of white cloth that serve as a lingoti. Raghunath Puri, Silverbeard, a tall sadhu with long arms, directed me to sit down facing Hari Puri Baba.

Pandit Shesh Narayan entered the room with a brazier burning with red coals from the havan between two iron tongs. The pandit, Hari Puri Baba and I formed a triangle, with the brazier in the middle, and the room started to fill with smoke.

With his eyes turned upward, the pandit intoned a river of mantra, magic syllables that flowed out of his mouth. I understood that he was invoking the great powers of the universe. At the end of each verse, each Vedic sloka, he would toss fragrant powders onto the glowing coals, pronouncing "Svaha!" consecrating the offerings in the name of the fire deity's wife.

I watched the white smoke rise from the coals, carrying the sacrifice of these sacred syllables to the gods. He dripped holy water into my right hand, then rice, flower petals, and more water, all the while intoning mantras. When he had completed the ritual, he took a small brass bowl, a katori, from the altar and commanded me in English to drink from it. The greenish liquid looked and smelled very strange.

"What is it?" I asked Hari Puri Baba.

"Oh, nothing much," he replied, "a substance to remove all your bodily impurities, a nectar that pleases nature."

"What's in it?" I asked.

"The five products of the cow: milk, curd, ghee, cow urine, and cow shit," he replied matter-of-factly.

"Really? And I'm supposed to drink this?" I asked, praying that he was making one of his jokes. It didn't taste as terrible as I thought it would. I imagined myself turning to gold as the liquid permeated my body. Pandit Ji turned and smiled at me as he left the room to us babas. Raghunath Puri placed the bundle in my hands.

"Now is when you ask me to make you my disciple, my shishya," Hari Puri Baba said.

I picked up the bundle and placed it at his feet, asking him to make me his shishya.

Raghunath Puri interrupted on a minor point. All I could understand was the word "guru."

"I am not his guru!" Hari Puri Baba shouted at him in English.

"You're not?" I was stunned. What was going on?

Pointing to the altar, Hari Puri Baba told me that, in fact, he was not becoming my guru but only my shakshi guru, a "witness guru" to my becoming the disciple of the lord of yogis, Guru Dattatreya, he who shows the Path. The small bronze icon of Dattatreya on the altar had three heads, those of the gods Brahma, Vishnu, and Shiva. Dattatreya is the naked one.

"It is by his grace that you enter this world of discipleship and knowledge," Hari Puri Baba said. "It's at his feet that you sit. He is your guru. I'm just doing my duty.

"He is there on the altar and also here in our circle, our little mandala, in the form of five sannyasis who walk the Path. These sannyasis will be your five gurus. I have many presents for you, and the first are your five gurus. Each will give you his own gift. My second gift will be the guru mantra, those syllables, those sounds that will anchor you to me, and through me to the Path, and act as a foundation and ultimate refuge."

Hari Puri Baba pulled the hairs on his chin and frowned. "Do you commit your life to the knowledge of God? To the knowledge of Self, the Brahmavidya?" he asked.

Because this was the first real vow I had taken in my life, I hesitated. What if I'm wrong? I asked myself. Maybe I shouldn't be doing this. And then I knew in my heart that either through this initiation and this guru, some other, or maybe none at all, I would always seek the Path of Knowledge. The vow I made to myself was the most important. "Yes, I do," I replied.

"Will you return to your village and abandon this guru/disciple tradition?" Hari Puri Baba asked me sternly. No, I answered him three times as he asked me three times. I knew that I could never return to my life in California.

Mangal Bharti, another of my five gurus, flung the ochre dhoti over my head. I heard a few sanctifying drops of water hit the dhoti, as the cloth was held tight by three gurus. Hari Puri Baba entered my ochre cave with knife in his hand. "Don't worry. This won't hurt a bit," he whispered, as he bent my head and sliced off the remaining hair with a rather blunt knife.

He took my shorn shining head in his hands and turned it so that the right side of my face was now facing his mouth. His breath tickled my eardrum. "Now close your eyes, concentrate, and listen very very carefully," he whispered even more quietly. Time stopped, there was utter silence, the world ceased to exist, the universe retreated into the void. And then the wind, a hot hurricane. My right eardrum exploded in flame as Hari Puri Baba's loaded breath entered it. In harmony with the ringing came the syllables, one after the other, holding onto each other, tied on a string: the guru mantra. It played way too fast, and I couldn't hear it properly. I didn't concentrate enough. The most important of mantras! How could I let my mind wander at a moment like this? Then he blew it into my left ear, and back and forth between ears, until three times it had reached each ear. As the cloth was pulled away, a chorus of

namah parvati pate

hara hara mahadev!!

greeted us.

Hail to Shiva,

that Lord of the

Lady of the Mountain!!

I was sent to the spring for a quick ritual dip, and then returned to the dark puja room, where I was made to remove my loincloth and stand naked before my five gurus. "He looks like a Muslim. He's circumcised just like them!" joked the balding Mangal Bharti, slicing one index finger with the other as if it were a scalpel. Everyone laughed.

"You look so funny!" laughed Hari Puri Baba, holding his sides. "Just like a big baby! You see, nothing in your hands, nothing on your body, you have nothing. See? No more luggage! By the authority vested in me by all the mad people of the world, I declare you cleansed of all sin!"

Ramavatar Giri grunted at Hari Puri Baba, showing him two strips of white cloth. "Oh yes," he continued, "your guru, Ramavatar Giri, wishes to give you the gift of the loincloth, the lingoti." Ramavatar Giri tied one of the white cotton strips around my waist, and made me double over the other strip, sliding it over the first, then covering my genitals, before tying it around the back. Then he tightened it.

"This gift of lingoti will push your vital airs, pranas, upward and awaken the sleeping goddess Kundalini deep within you. It will make you strong, able to perform austerities, and sharp of intellect. It will direct your attention up, past the five elements that constitute the material world, to the spiritual world," Hari Puri Baba instructed me.

Raghunath Puri mixed white ash, called vibhuti, with water in a small brass bowl to make a paste. Vibhuti is no ordinary ash, but a substance of power. "Vibhuti is from the sacred fire, the dhuni, which never goes out. We make all our sacrifices into the dhuni, and use it as a means of exchange with the powers of nature. It has in it the fruit of countless sacrifices, and indeed is illusion burned to ash. Duality cannot stand the test of fire. The gift of vibhuti is your material wealth and your clothing. It is the ultimate medicine, it can heal, but then you can make anything you want out of it. It's primal stuff," he said. Raghunath Giri applied the thin paste to my forehead in three horizontal lines. He then handed me the bowl so that I could smear the mud of ashes like a mask over my face and body.

As he repeated a mantra, Amar Puri Baba slipped the rudraksha bead on the janeu string, over my head.

"My brother, your guru, has given you the gift of rudraksha. This bead, which as you can see, is a seed from a tree, contains the power of discipleship. It is the manifestation of the covenant between humans and the Great God Shiva that the Path of Knowledge would be passed down through the tradition of discipleship. Shiva's most uncompassionate manifestation, Rudra, shed a tear of compassion for mankind, and this became the Rudraksha tree. It pulls the pranas upward, and can be worn anywhere on the upper body to focus energy, but the one the guru gives you is worn over the heart, where your connection with the guru is established."

Mangal Bharti concluded the giving of the five gifts by wrapping me in the ochre dhoti, creating little sleeves for my arms as he folded and tied the cloth in the traditional sannyasi way. "This final gift of the five is your protection and sheltering of Mother Earth. You see, it is the color of her soil, ochre, her life-blood. You see how long this fine cloth is when unfolded? It is a flag marking that you are in her hands, and that you are on the Path."

From the waist folds of his own dhoti, Amar Puri Baba pulled a hundred-rupee note, and a rupee coin. He put the money in my hand and motioned to me that I should give it to Hari Puri Baba. I went to put it in his hand, but Amar Puri Baba grabbed my wrist, directing me to place the money under Guru Ji's foot.

"Areh wah, baccha!" Guru Ji said. "This is a large dakshina. Well, you are from London, or some such place, where the streets are paved with gold, no?" It mattered little that Amar Puri Baba had given me the money nor that I was as broke as any starving Indian peasant. In that moment, cash was not just money. "This is the sacred fee for the teacher. What do you call it, your tuition, no?" Hari Puri Baba said, chuckling. Holy money, I thought.

Amar Puri Baba put my hands together in an attitude of prayer.

om namo narayan!!

om namo narayan!!

He saluted, and I repeated,

om namo narayan!

"This is the mantra we use to greet the guru, and to salute each other, Om namo narayan!" Guru Ji instructed me. I was then shown how to make obeisance to the gurus-omkars-every morning and evening to all gurus. Squatting flatfoot, with my hands on the ground, I touched my thumbs to my pinkies and learned how to count on my fingers as I repeated:

om guru ji! om dev ji! om datt ji!

om swami ji! om alakh ji!

om namo narayan!!

Each time I made a mistake, and I made many, I was corrected. I performed five cycles to each guru, bending down, touching my forehead to my thumbs at the end of each cycle. Amar Puri Baba provided me with a rupee coin to give to each guru as dakshina.

Invoking Shiva (Lord of the Lady of the Mountain), my gurus shouted:

namah parvati pate

hara hara mahadev!!

Raghunath Puri Baba took the sacrificial coconut in his hands and examined it. The small, round, bearded fellow was not to have a surgical beheading. He was brutally smashed on a rock. Cleanly. One head became two skull bowls, each spilling sacred liquor. Smashed open as an offering to the gods, to mark the initiation and begin the marriage. Like smashing the wineglass at a Jewish wedding.

The coconut was full of milk. "A good sign," said Hari Puri Baba. "You will be a fruitful disciple; see how much milk there is!"

Raghunath Puri then scraped off the coconut flesh and mixed it with gur, natural brown sugar made from boiling and then cooling sugar cane juice, that solidifies into golden brown cakes. "The taste of the goddess Lakshmi," Hari Puri Baba said. He picked up a small chunk of gur with his fingers and put it in my mouth. I then, on cue, placed a chunk of gur in his mouth. Raghunath Puri studied me for a moment and asked, "Gur sweet, or guru sweet?" I answered, "Guru." He repeated the question twice more and each time I gave him the right answer. He lifted the thali, or tray, over his head and shouted three times,

Mahant Hari Puri Baba Ji ka chela . . .

Ram Puri Ji!!

Having made the pukar, the announcement to the three worlds that I had become Hari Puri Baba's disciple, and that my new name was Ram Puri, he distributed the mix of coconut and gur first to the sadhus present, then sent the thali out to the other sadhus and to the Brahmins making the havan, the fire sacrifice.

The sacrament of the five gurus, the panch guru sanskar, was complete, the guru–shishya relationship initiated. Now that I was his shishya, Hari Puri Baba told me that he would have me made a sannyasi at the coming Ardh Kumbh Mela in Prayag Raj, Allahabad, after Makar Sankranti, when Surya the Sun entered the house of Makar the Crocodile, approximately Aquarius. Until then I would need training, lots of training.

I felt very different after the initiation. I felt I could walk on air (without crashing to the ground). I knew that if I bought a lottery ticket, it would be the winning one. I stared at my shaved head in the mirror. It was naked. That's not the me I used to know, I thought. But I wasn't a new person; I just carried a little less baggage.

I had made a solemn vow before holy men. That night before sleeping I sat for a while at the spring, surrounded by the gods and prayed that I might be worthy of my intentions. My bare head felt cold, unprotected from the elements.

om purnamadah purnamidam

purnat purnamudacyate

purnasya purnamadaya

purnameva vasisyate

om shanti shanti shantih !

That is whole, this is whole.

From the whole, the whole is manifested.

When the whole is taken out of the whole,

The whole still remains!