The release of director Sean Penn’s film Into the Wild renews the controversial debates generated by Jon Krakauer’s book of the same name. At their roots, these charged deliberations have little to do with Penn’s ambitious directing or Krakauer’s compelling prose and focus instead on our collective interpretations about the tale’s real-life protagonist, Christopher “Alexander Supertramp” McCandless.

Now the stuff of common lore, the details of McCandless’s dramatic departure from mainstream culture and his traumatic demise in the Alaskan wilderness provide fodder for fierce debates about everything from the virtues of drop-out culture to nitty-gritty strategies for extended survival. Too many discussions have honed in on a crass character analysis of the deceased, describing the young vagabond as a naïve kook and arrogant idiot – just another white male iconoclast who, in hoping to commune with the land, has only further conquered and contaminated it.

One especially blunt commentator that Krakauer cites puts it this way:

“Such willful ignorance amounts to disrespect for the land and paradoxically demonstrates the same sort of arrogance that resulted in the Exxon Valdez spill – just another case of under-prepared, over-confident men bumbling around out there and screwing up because they lacked the requisite humility. McCandless’s contriverd asceticism and pseudoliterary stance compound rather than reduce the fault.”

Even if these assessments are the inevitable and necessary counterpoint to Krakauer’s and Penn’s sympathetic and romantic portrayals of a wild young hobo monk, inspired by the likes of Jack London and Henry David Thoreau, I find the posthumous focus on the precarious minutiae of McCandless’s impractical tactics to be an unnecessary distraction motivated by a moralism as harsh as the one that apparently motivated McCandless. Truth be told, I count myself among the staunch McCandless apologists and find Krakauer’s book, Penn’s film, and rocker Eddie Vedder’s soundtrack to be an emotionally haunting and spiritually memorable trilogy – poetic meditations on the possible evacuation routes from the perpetual madness of civilized insanity and technophilic postmodernity. Beyond my appreciation for the story itself and the care with which its tellers convey to a wide audience, we can locate within it many layers of commentary on the alienating aspects of mass society, as well as current speculations about a coming cataclysm that may force many of us to change our relationships to nature and each other.

The selfishness and sadness about how this tale ends, in sacred foolishness, deflects some aspects of courageous dissent that come with the clarity and ferocity of McCandless’s initial break with society. While Abbie Hoffman once burned money as a public prank, the self-made mythmaker of Alexander Supertramp burned his last stash of cash as private prayer – a perverse theater of the self that takes the voluntary simplicity rap to its youthful extreme. This brash purge of modest barter power came after McCandless donated a much larger sum to Oxfam, shredding bank cards and personal identification, and generally denouncing his preparation for participation in the world – a likely path guaranteed by his upper-middle class credentials and recent college degree.

Shot entirely on location in the places that McCandless visited, Penn’s profound rendering of Krakauer’s book gives off an emotional power and visual weight wrought by precise and hungry cinematography. When tramping under the assumed name of his adopted archetype Alex, McCandless is often carefree and careless, yet compassionate to the people he encounters. Penn captures the elation of Alexander Supertramp’s early adventures with celluloid passages that inevitably conjure thoughts of other great American road art, from the epic historical movie Easy Rider to Jack Kerouac’s On The Road and its “bop prosody” – jazz-like riffs of wide-eyed drunken beauty. Despite the unwashed material poverty of it all, the early chapters of the Supertramp-McCandless odyssey offer a sense of unencumbered jubilation, to be later matched by the conclusion’s emaciated devastation.

Once in Alaska, the lonely spartan reality of the McCandless quest offers a poor example of how to live as a solitary forager-hunter. From the point of view of what has been called “re-wilding,” people have the potential to recover lost lessons from our ancestral heritage, learning practical and tactical skills that might serve the outback escapist today and the person who outlasts the catastrophe tomorrow. The survivalist critique of the McCandless story avoids condemning survivalism. From either the naturist or the collapsist point of view, what’s wrong with this picture stems not from the possibility of retreat but with the errors that lead to the inevitable defeat.

We will never know for certain all the factors that fuel McCandless’s starvation, and I wish to engage in an entirely different kind of speculation. As much as there is some Alexander Supertramp within me, I never “pulled a Christopher McCandless” when I was young because of the love I have for my parents. Today, I resist the temptation for the illusory exultation of escape in part because of the love I feel for my partner and children. In leaving the noise of society for the silence of Alaska, McCandless found that he could not silence the noise of his psyche, a noise that almost pulled him back from the brink.

Even in the evils of a malevolent society that people of conscience for centuries have rejected, there always remain the seeds of a different society. Rather than reject the social entirely, McCandless meant to follow the path of the temporary monk. When Krakauer extrapolates from the journal that McCandless kept, his book suggests that before McCandless’s life ended, the lonely exodus was about to end. Indeed, before the fatal transport to the other side, McCandless was likely “ready, perhaps, to shed a little of the armor he wore around his heart, that upon returning to civilization, he intended to abandon the life of the solitary vagabond, stop running so hard from intimacy, and become a member of the human community.”

The question for us, then, is how to preserve “human community” without “returning to civilization.” Indeed, McCandless’s accidental and individualist suicide wish might be instructive in helping us avoid collective suicide. Rather than a rejection of the social, anarchism might revise how the social gets organized. Far less romantic than the burnt dollars and torched flags of pure rejection, compromise and cooperation can still provide motifs for communal change. At the end, investigating Alexander Supertramp’s individualist anarchism encourages us to invest in a nuanced rejection of pure individualism in favor a social and socialist anarchism that supports and honors already the individual.

Interestingly, McCandless visits just such a vision before departing forever. Even though his excruciating excursion fails to extol the larger narrative of individualist escapism, it grants some gravity to the gracious necessity of collaborative and communal escape. Clearly, the most heartfelt moments in Penn’s film do not take place in a perfect, out-of-the-way place. Rather, having rejected his family of birth, McCandless finds a family just by wandering the earth. The relationships McCandless cultivates with fellow tramps and travelers demonstrates the undeniable ubiquity of love.

One of the movie’s most memorable sequences takes place at “the Slabs” – an amazing autonomous zone that Krakauer describes as “an old navy airbase that had been abandoned and raised, leaving a grid of empty concrete foundations scattered far and wide across the desert.” In this no-go zone, we witness a kind of cooperative escapism. Like festivals, gatherings, and communes, places like this could grow to be not only an antidote to the disaster of individualism depicted in McCandless’s miserable fate, but also an answer to the inauthentic virtual worlds where so-called “social networks” exist entirely in the ether. In words that could have been scribbled by Hakim Bey, Krakauer depicts “some five thousand snowbirds and drifters and sundry vagabonds” who “congregate in this otherworldly setting to live on the cheap under the sun.”

Indeed, when he constructed the notions of temporary and permanent autonomous zones, Bey probably envisioned places like this: “The Slabs functions as the seasonal capital of a teeming itinerant society–a tolerant, rubber-tired culture comprising the retired, the exiled, the destitute, the perpetually unemployed. Its constituents are men and women and children of all ages, folks on the dodge from collection agencies, relationships gone sour, the law or IRS, Ohio winters, the middle-class grind.”

Krakauer contemplates what he calls McCandless’s particular “variety of lust,” a monastic passion seduced more by open spaces than sexual places. From the lessons of this lust, we might develop an equally devoted passion to creating a slab of reality not unlike the Slabs: a new autonomous zone where rejecting the daily grind does not require us to lose our minds; where we can reject society without ejecting the social, and form loving and lasting contacts with other souls similarly disenchanted with civilization.

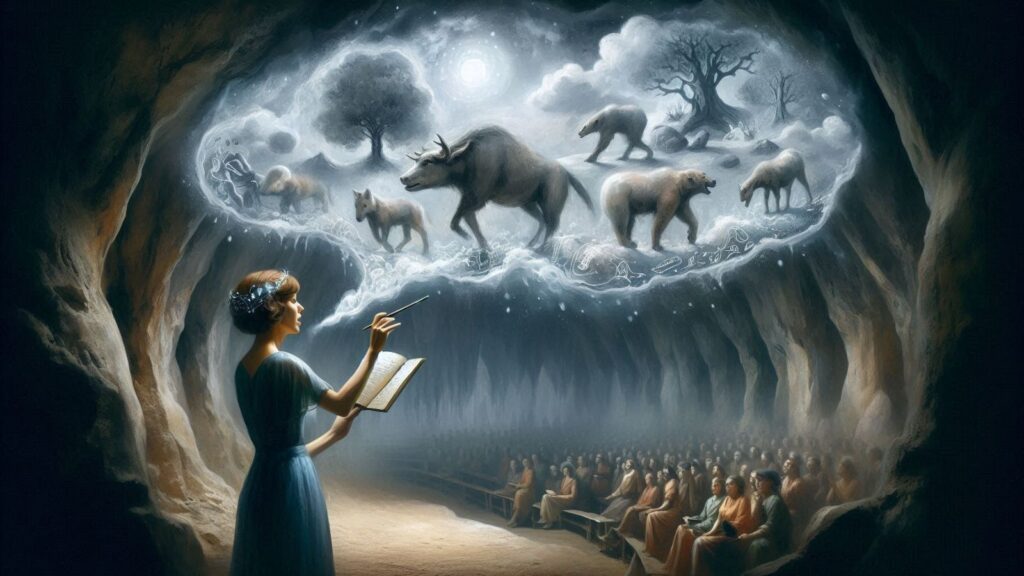

Image credit: Into the Wild by Travis S., used under Creative Commons license.

This essay also appears in the current edition of Fifth Estate, North

America's longest-running, anti-authoritarian periodical. Please visit

http://fifthestate.org for more information.