The following is excerpted from Culture and Horticulture by Wolf D. Storl, published by North

Atlantic Books.

No joy is so great in a life of seclusion as that of gardening. No matter what the soil may be, sandy or heavy clay, on a hill or a slope, it will serve well. –Walafrid Stabo, Horulus, ninth century

Agriculture started about ten thousand years ago, as archeological evidence from Asia Minor suggests. Ten thousand years is a long time for observations to accumulate and techniques to develop. Indeed, agriculture and culture are intimately linked, as anthropologists have shown many times in relating the connection of quality and form of lifestyle with various subsistence patterns. It might be claimed that a healthy agriculture is the basis of a healthy culture and healthy culture implies a healthy agriculture.

Early forms of agriculture include the irrigation practices of Mesopotamia, Egypt, the American Southwest, and other parts of the world; and swidden (or slash-and-burn) systems developed in the forested areas of the world.

Swidden entails cutting or girdling trees; burning brush, thus releasing nutrients in the ashes; and sowing or planting food plants in the spaces. The soil is usually exhausted after a few years, forcing the primitive agriculturists to move to another location, to return to the same plot for a new cycle of clearing, burning, and planting perhaps even after a number of decades. When the forest has regrown the swidden farmers often return to the same area for a new cycle of clearing, burning and planting. Some of the early American pioneers practiced swidden, as did the Native Americans, for instance the Iroquois, who subsisted on the "three sisters" of maize (corn), beans, and squash.

The early ancestors of the Europeans practiced slash-and-burn agriculture until the time that the population increased and a more stable way of life developed, when more permanent forms of agriculture were devised. The fusion of barbarian and Roman lifestyles brought about the feudalistic, medieval way of life. Most of the populations were peasants engaged in agriculture, while a small percentage of the population, the nobility, provided protection, ensuring the peaceful agricultural cycle would not be unduly interrupted. The clergy provided guidance in the moral and ideological sphere.

Generally, land was held in common, with each family tilling what it needed to survive and to pay as tax to the nobility and the church. If the family grew larger or became smaller, the amount of tillage in tenure would vary correspondingly. The crops were grown in a three-field system of rotation. One field was planted with summer crops, one with winter crops, and one lay fallow. The fallow field was permitted to grow over with weeds, which helped restore the fertility to a large extent. The fields were also manured from time to time. On the average, the yields were low, but the fertility of the soil remained fairly constant. The animals were grazed on the common lands beyond the confines of the village and the common woodland served as a source of firewood, herbs, berries, beechnuts, and acorns for swine in the fall, etc.

A whole way of life and a cosmology supported by centuries of observations and lifetimes of experience were linked with early agricultural systems.

There was nothing resembling modern scientific research at the time. The closest to such research was the activity in cloister farms and cloister gardens. Here, medicinal herbs were grown; along with vegetables such as carrots, leeks, onions, cucumbers, cabbages, lettuce, peas, parsnips, rampion, and chards; as well as some that are nowadays considered weeds, such as mustard, purslane, and lamb's-quarters. Plants for dyeing cloth were there, such as madder (red), weld (yellow), or woad (blue), and teasel flowers, used for combing the fibers or raising the nap. Plants rich in symbolic meaning, such as the rose, the lily, and the violet, were tenderly cared for. New insights were gained through meditation and observation, rather than by a method of controlled experiments. Old knowledge, the horticultural and agricultural writings of the old Greeks and Romans (Pliny the Elder, Cato, Theophrastus, Virgil) were kept by the monks and eventually filtered down to the illiterate country population in the form of oral folklore.

The cosmology of the Middle Ages was suffused with the belief in numerous "supernatural" beings. Various elemental spirits were at work in nature: gnomes in rocks, nymphs in water, sylphs in the air, and fire spirits in fire and warmth. Each had certain tasks: the gnomes helped form the roots; the nymphs helped form the leaves; the sylphs wove the flowers; and the fire spirits helped the fruits ripen. There were other nature spirits, house spirits, and seasonal spirits that were taken account of by prayer, propitiation, or magic. Many of these, of pagan origin, had acquired a Christian veneer, reappearing as saints or angels. Each day of the year had a saint's name, rather than merely a number, and the nature of the day was associated with the nature of the saint. Thus, for example, it was noted that May 12, 13 and 14, bearing the respective names St. Pancras, St. Servatius, and St. Boniface, usually bring cold weather and the last frost. They were known as "The Ice Saints." Some saints had prophetic characteristics, such as St. Urbain (May 29): whatever the weather on St. Urbain, it would be the same later during the haying season.

Certain saints' days were good for sowing this or planting that, harvesting this or reaping that. The saint himself was thought to be active in helping the plants sprout, grow, ripen, etc. — just as a person born on a certain day would have a special relation to the saint of that day and often would be named after the saint, as is still the custom in rural Latin America. The craft of gardening, especially vegetable gardening, was watched over by St. Fiacre (August 30), with an open book and a spade. The saints remind one of the functions of the revered powerful ancestors among the agricultural people of Africa and China.

The old gods of the Romans and of the Slavic, Baltic, or Northern peoples did not disappear with the coming of Christianity — how could they, since they symbolized the forces that constitute the world? They continued to exist, metamorphosed into beings acceptable to Christian ideology (i.e., the thunder bearer Thor becomes identifiable as the archangel Michael; Mercury or Odin are metamorphosed into Gabriel, the messenger; the Celtic spring goddess Birgit becomes St. Bride; the ancient Mother Goddess reappears as Mary, etc.) or, in the later Middle Ages and Renaissance, the gods were associated with the spheres of the seven planets (Saturn, Mars, Jupiter, the sun, Venus, Mercury, and the moon) as expressions of the various heavenly spheres.

These spheres did not just exist "out there" but were active on earth as well, through mysterious influences (in-flowing) and correspondences. The signature of the planets marked every creature, thing, or state of being. For example, Jupiter's signature is found on earth in the color yellow; in the liver and its functions; in the metal tin; in plants such as dandelion, maple, liverwort, and others; and in the psychic characteristic of wisdom or the negative character trait of debauchery and drunkenness. The signature of Mars, to give another example, is found in the color red; the gall bladder; blood; iron; courage, fierceness, and anger; fiery steeds; and plants such as the solid oak, nettle, hops, plantain, etc.

The fixed stars, which form the background against which the planets (Greek planétés = "wanderers") move and operate, were considered to belong to a higher realm, a more majestic sphere. This region, divided into twelve zones, constitutes the zodiac, twelve archetypal forces that influence the events here on Earth, modifying and influencing the planetary forces. Thus, a sun shining from Leo (in July) is a different sun than that shining from another background, such as from Pisces (in February). A full moon shining from Taurus, the cosmic bull, has very different qualities than a full moon, in Scorpio, for example. The sphere of the fixed stars, the zodiac, was experienced anthropomorphically as a giant man, a Meganthropus. Aries was considered to constitute the head of this macrocosmic man, Taurus, the neck, Gemini, the shoulders, and so on down to the feet, which were in Pisces. Each of these zodiacal signs was assigned to one of the four elements (earth, air, fire and water) and had great relevance as to when anything should or should not be done, when to plant, sow, till, cut nails, cut hair, cut timber, etc.

Predictions and prescriptions based on saints' days, planetary and atmospheric conditions, and also on observations of animal behavior were stated as rules, often fitted into rhymes and couplets and passed on through the centuries by word of mouth. The rules are countless but we can give a few examples, such as the following weather oracles:

St. Vincent's sunshine

brings corn and wine.

This refers to the prediction that if the weather is clear on the twenty-second of January, St. Vincent's day, the harvest will be bountiful.

When April blows his horn [thunders]

it is good for hay and corn.

All the months of the year

curse a mildish Februeer.

Green Christmas, White Easter,

That is to say, if Christmas is mild, it will surely snow around Easter.

When clouds appear like rocks and towers,

the earth's refreshed by frequent showers.

In the waning of the moon

a cloudy morn, a fair afternoon.

Other sayings concern the proper times to engage in this or that activity:

Cut herbs just as the dew does dry

Tie them loosely and hang them high

If you plan to store away

Stir the leaves a bit each day.

Sow peas and beans in wane of the moon

Who soweth sooner, he sows too soon,

That they with the planet may rest and rise

And flourish with bearing most plentiful and wise.

The moon in September shortens the night

The moon in October is the hunter's delight.

Fruit gathered too timely will taste of wood

will shrink and be bitter and seldom be good.

At hallow tide [All Saint's Day, November 1] slaughter time

entereth in

and then doeth the husbandman's feast begin.

As January doeth lengthen

winter cold doeth strengthen.

The provident farmer on Candlemas Day [February 2]

has half of his fires [wood] and half of his hay.

When the likker's low

or ceases to stew,

The farmer doeth know

the winter is through.

Onion skin very thin

mild winter coming.

Onion skin thick and rough

coming winter's cold and rough.

There are numerous sayings that regulate the right time to sow, plant, and reap and in which astrological sign to do so; and finally, there are some of definite humor, lest anyone become too serious, such as the following:

A husbandman can surely know

on the thirtieth of February there's never snow.?If rain falls on the rye,

the wheat and clover won't stay dry.

On Sylvester [December 31] snow, then clear

no more snow the rest of the year.

This, then, is what constituted the "science" of the old agriculturist. It was a science that was not yet divorced from religion, psychology, or everyday life; it was rather part of a holistic way of being. Their agriculture was a sacred way of life, as Jacob Burkhardt once remarked, not just a business to be carried on.

As the peasantry became more literate, these rules found their way into Farmer's Almanacs, or into publications such as Thomas Tusser's Five Hundred Points of Good Husbandry (1683), which was a standby for the New England pioneers. It is surprising that despite education and scientific progress, the almanacs are still being used by a number of farmers and gardeners today; but the users are generally considered to be backward, quaint, and superstitious. These almanacs contain a calendar for the year with the daily corresponding astronomical data, a weather forecast, list of the holidays, tips on gardening, farming, fishing, horoscopes, recipes, weights and measures, and other items. Popular almanacs currently printed in the United States include Old Moore's Almanac, first published in 1697, The Old Farmer's Almanac (since 1792), Grier's Almanac, first published in 1807, and Baer's Agricultural Almanac of Lancaster, Pennsylvania since 1825.

The medieval way of life and cosmology did slowly come to an end due to a variety of demographic, socio-economic, and political factors, all of which are common history. By a series of enclosures, wealthier landowners saw to it that the common land disappeared from the manor. Country folk were forced off the land and absorbed as laborers in an industrial revolution that has not come to a halt since. Many peasants immigrated to the newly discovered continents and found themselves in new and unusual ecological and socio-economic situations.

Other factors, also, helped destroy the old way, such as the calendric reforms of Pope Gregory XIII in the sixteenth century, whose replacement of the old Julian calendar brought about a shift of eleven days and fixed the beginning of the year in January — instead of March 25, as had been the case for centuries. This very much confused such issues as the saints' days. Also, by this time, the gradual shifting of the relative positions of the planetary cycles to the zodiac (i.e., the spring equinox) had caused a discrepancy between the dates of the conventionally fixed signs and what could actually be observed in the nighttime sky.

Finally, the new skepticism concerning old traditions and the empirical-logical scientism of the Enlightenment detracted greatly from the credibility of such folk rules. Many of the folk rules were applicable only in certain restricted ecological and geographical regions, and did not lend themselves to the formulation of general rules, as scientific standards demand.

Early settlers brought their rules and almanacs with them to America, but found them difficult to apply under such novel circumstances. Here and there they have managed to hold on to them, and even to found new local adaptions, as with the Amish of Pennsylvania and the mountaineers of Appalachia.

The Foxfire Book lists a number of such beliefs among the Appalachians of Rabun-Gap Nacoochee in Georgia. Rules about Groundhog Day, on February 2 (if the groundhog sees his shadow, there will be six more weeks of winter) and about poison ivy (leaves of three, let them be) in the Midwest are of this nature. In the Williams region, in southern Oregon, there is a rule about Grayback Mountain:

Seven on Grayback, heavy with snow,

all summer long, water will flow.

This permits the farmer to plan management of his water resources for the coming summer since it refers to whether the springs will dry up or not. Though here and there these rules live on, a newer philosophy and commercial orientation have little use for such passed on traditions and homegrown observations that do not lend themselves readily to controlled experiments. And it is not to be denied that many such rules seem trite, redundant, or even nonsensical.

The Newer Agriculture

With the rise of the new experimental, scientific spirit, steady improvements in agriculture and horticulture can be registered. Jethro Tull invented drilling grain instead of broadcasting it, which permitted "interdrilling" or cultivating. At the same time in the 1730s, Lord Townshend of Norfolk developed a modern system of crop rotation: a four-year rotation of wheat, turnips, barley, and clover or beans with manure plowed in to boost production. New varieties of livestock and plants were bred. The yield per acre was significantly increased. In the 1810s, Albrecht Daniel Thaer discovered the significance of humus, and legumes were introduced as green manure.

The chemist Justus von Liebig inadvertently provided the impetus for chemical agriculture, which became the backbone of twentieth-century agribusiness. Von Liebig carried on convincing experiments in which he incinerated plants and analyzed the ashes for their content of elements and minerals. He reasoned that when a crop is harvested, a certain percentage of nitrogen, phosphorous, and potassium (NPK), as well as calcium, magnesium, and others are removed from the soil. In due time, the soil will deplete unless these elements are replaced in a chemical form or in an organic form (manures or composts) because nitrogen is nitrogen, phosphorus is phosphorus, and potash is potash, no matter in which form they are found. In 1842, a disciple of Liebig, J. B. Lawes, began to experiment with fertilizers on his estate of Rothamstead in Berkshire.

He succeeded in producing and marketing superphosphates extracted by means of "vitriolization" from the bones from slaughterhouses and even old battlefields and from mineral calcium phosphate. In 1843, J. H. Gilbert, a chemist, joined him and helped wed chemistry to agriculture. Continuous experiments have been run in Rothamstead with basically three fields. One field has no fertilization, one is dressed with manure, and the other is given pure chemical fertilizer. The chemical fertilizer holds its own against the manure, while, of course, being a lot cheaper and easier to manufacture and handle.

The experiments of Rothamstead seemed to show the way for a future of prosperity; the black horse of the apocalypse, famine, was forever banned; the old country folks' dream of the "land of cockaigne" ("Schlaraffenland," the land of milk and honey) seemed to come true. The flaws in the theory did not become evident until this century. For the time being, a completely materialistic worldview had it that the plant was considered a chemical factory needing a certain input of NPK, water, CO2, and energy, which provide an output of sugars, starches, O2, etc.

Phosphorus could be derived as a side product of the ever-expanding steel production-from the slag. Potassium was found in underground deposits, as those of Strassfurt, Germany. Nitrogen was derived from the sodium nitrate deposits of Chili, the famous Chile saltpeter, and from side products of coal-gas production. Farmers were, however, on the whole, slow to take the bait and before the 1890s, few actually used chemical fertilizers.

The First World War gave a big boost to chemical fertilizer usage. The Allied blockade had successfully cut the Central Powers off from imported food and from Chili saltpeter. Nitrogen is, of course, the basic ingredient of the ammunition that keeps the armies in the field. German scientists developed a method of fixing nitrogen from the air, which is composed of 79 percent N, as an inert gas. Thus, problem-solving in the arms industry and the fertilizer industry is a result of the war, with nitrogen salts becoming readily available and food production being subsumed under the war effort.

It is a similar story from the Second World War. Much research had been done in between the wars in chemical warfare materials, and poisons were stockpiled. When the second war broke out, both sides were afraid to use these stockpiles, so they became diverted toward the war against insects. DDT, used for the first time successfully by the Allies to save the liberated city of Naples from a lice and flea epidemic, was the first of a number of chlorinated hydrocarbons that would wage war against a healthy environment. The unfortunate and unforeseen effects are only now being realized.

The Vietnam War was not without its "spin-offs" for agriculture: complicated defoliants and herbicides were developed further and productive capacities expanded. Though that war is over, the stockpiled chemicals are marketed and passed off to the farmer and to county agencies that spray roadsides and irrigation canals, irrespective of the ecological damage incurred. It is not surprising; what other fruits can be borne out of war research, which is motivated by fear and hostility?

Copyright © 2013 by Wolf D. Storl. Reprinted by

permission of publisher.

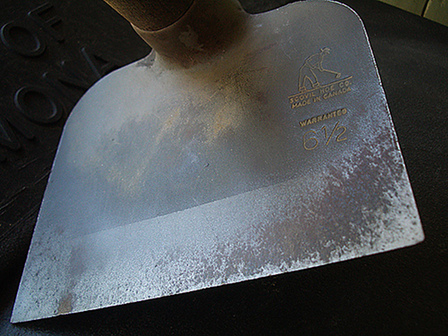

Teaser image by The Marmot, courtesy of Creative Commons license.