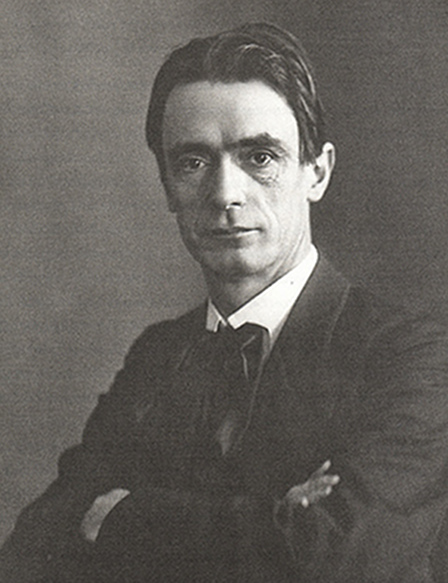

Join Conner Habib for the Evolver video webinar, "Anthroposophy 101: Rudolf Steiner, Freedom, and the Western Esoteric Tradition," tomorrow, August 22. Click here to learn more.

Who was Rudolf Steiner and who’s working with Steiner’s ideas today?

Rudolf Steiner was a scientist, philosopher, and spiritual thinker who lived in the late 19th and early 20th Century. He produced a huge body of work, including thousands of lectures, a whole shelffull of books, and a building in Switzerland called the Goetheanum. His work, and the work and perspective of those who are influenced by his ideas, is referred to as anthroposophy.

His influence is felt most strongly around the world in the system of agriculture he created, called biodynamic farming; in Waldorf schools; and in CSAs (community-shared agriculture) which he laid the foundations for. But Steiner also created a new form of medicine, bee keeping, a way to create stained glass, jewelry making, and more. His spiritual perspective was even poised to inform the structure of European government around World War I.

Steiner’s work has also deeply influenced scientists and ecologists; Rachel Carson was inspired by the work of anthroposophists, for example.

So there are tens of thousands of people interacting with anthroposophical ideas, whether they know it or not. Some people directly influenced by Steiner’s work include novelist Saul Bellow, writer CS Lewis, actor Jennifer Anniston, scientist James Lovelock, artist Joseph Beuys, and more.

How did I get interested in Steiner?

When I was in grad school, Rudolf Steiner’s name kept popping up in reading I was doing, but I never really looked into it. When I went to an environmental conference with my teacher and mentor, biologist Lynn Margulis, I came across a brochure for a place called the Nature Institute, which had a three month-long program on Goethe’s method of science.

Even though I was in school already, Lynn said, “If you can get into that program, you’re going.” You didn’t argue with Lynn Margulis about stuff like that. So I got in and went, having no idea that Goethe was one of Steiner’s main influences. Suddenly, I was soaking in anthroposophy. I got an apartment that was literally next to a biodynamic farm and across the street from a Waldorf school. It was the perfect fit for me: I was in grad school for creative writing and biology, and anthroposophy bridges the gaps between the arts and the sciences. Eventually I was reading Steiner’s lectures, and even though I didn’t understand any of it at first I felt a feeling of growth as I worked to comprehend what he’d said.

What are the basics of anthroposophy?

There aren’t really any basics explicitly laid out, partially because anthroposophy is so far-reaching and complex, partially because it evaded dogma, and most importantly because anthroposophy is so deeply individualized. Everyone’s ideas of what the fundamentals are will be different.

That said, there are certain threads that seem to show up again and again in Steiner’s work, so I think of those as my fundamentals.

They are:

* The principle that thoughts are as real as objects. In other words, we need to understand that the thought-world is as important as the material world. In the current mainstream worldview we tend to dismiss thoughts as illusory, but Steiner would say they are just as foundational to reality as material is.

* The evolution of consciousness. Steiner taught that consciousness evolves over time. He didn’t just mean that the content of our thinking evolved, but that the structure of thought, feeling, and perception evolved. The difference between what a person six hundred years ago thought and what we think today isn’t just a difference of what but how. Many anthroposophical thinkers, like writer Owen Barfield, developed this work – pointing to the forms of language we use and art we make as evidence for this.

* There is a spiritual landscape populated by spiritual beings, and these beings are constantly interacting with us. For anthroposophists, these beings are not merely conceptual metaphors, but actual entities. There’s a vast hierarchy of creation that can be understood only by studying, contemplating, and considering these beings. This is the hardest principle for people unfamiliar with anthroposophy to deal with, so Steiner goes into great detail about what he means and helps to assist people to discover this on their own (or to reject it!), rather than just taking his word for it.

* The highest principles of being are freedom and compassion. By freedom, Steiner means thinking, feeling, and acting with real intention, rather than being led by compulsion. Like many spiritual thinkers, Steiner understood that even when we believe we’re acting out of freedom, we are very often not. His best solution for this was to work on having compassion for others as a way to develop freedom for yourself and to cultivate an atmosphere of freedom for others to develop in. If you didn’t buy any of the other stuff about anthroposophy, but got this part down, you’d have a good handle on it. As usual, Steiner doesn’t just assert this, but gives practical guidance on how to work on this faculty.

How did Steiner use his spiritual insight to create practices and change in the world?

Steiner’s work was about spiritualizing the material and materializing the spiritual, so that we could heal the rift we perceive between the two. To that end, his efforts were always holistically inspired.

For example, biodynamic farming isn’t just about making better tasting blueberries. It’s about healing the soil the blueberries grow on, creating a healthy environment for the farmers, and creating a farm for those blueberries in which each component — the cows, the other plants, the farmers — act as “organs” in the “body” of the farm “organism.” (By the way, the blueberries taste delicious.)

Another example is the Camphill movement, which works with people who have learning and mental disabilities. Rather than just shuffling them away or trying to “fix” these people, who are residents at the Camphill communities, Camphill considers them as whole human beings, with their own lessons to teach and lives to live. They’re no more deficient or in need of “fixing” than you or I, and our destiny is intertwined with theirs.

A third example is Steiner’s work with money (currently pioneered by organizations like RSF. Steiner wanted us to reconsider our relationship to money, and rather than demonize it, elevate it into its proper place. Money, he taught, was actually brotherhood. It revealed to us our relationships when we interacted with strangers and people we know in exchange. So to help improve money, we need to restore it to it its principle of caring relationship.

Those are just three examples in the huge web of Steiner’s efforts to bring the principle of love and spirituality to a world that was becoming heavier and heavier with material and consumerist impulses. They all stem from the principles discussed above, which Steiner wrote and spoke about and enacted his entire adult life.