Over the course of the following decade, I got four more tattoos. All of them fairly small (on my wrists and the back of my neck), aside from the prominent arm band tattoo that I designed and drew myself and got tattooed on my right arm when I was nineteen. I admittedly didn’t think a lot about the tattoos I was getting over the years, but I did notice every time I had the inspiration to get a tattoo, it coincided with a time in my life when I was going through a major challenge, crisis, or transition. The tattoos signified something for me about change, self-determination, and self-ownership. I also just loved the experience of making my body into its own unique art piece.

This past month, I got my first large scale tattoo done in Nepal, which was by far my most ambitious statement. A torso piece that starts on my lower pelvis, circles like a vine across my stomach and ribs, weaves in spirals up my back, before finally curling itself over the top of my shoulder. The tattoo itself took eight hours to finish, and I refer to it as Black Fire. The piece has multiple layers of meaning for me, some that were conscious when I got it and some that were unconscious and have continued to reveal themselves over the past month.

As a writer, I naturally wanted to write something about the meaning behind my tattoo and what inspired me to get it. I also wanted to comment on the larger cultural trend of tattooing that has skyrocketed in popularity among young women in the West over the last decade. Therefore, I designed this article to be part historical excavation, part feminist inquiry, part erotic imaginary, and part intimately personal reflection on the many meanings behind tattoos today. My aim is to reach a more nuanced understanding of the place of tattoos on women’s bodies in contemporary culture, and what they have meant historically; including all the contradictions and conflicts they raise about beauty, power, sexual agency, and sexual objectification.

From Ice Men to High Society Women

Tattooing itself is far from a recent phenomenon, but it has risen to an entirely new level of popularity in North America over the last few decades, particularly for women. In 2012 a poll confirmed that, for the first time in history, women in the U.S. were getting tattooed more than men (23% of women compared to 19% of men). This may come as a surprise to those who still equate tattoos with male sailors, underground gangsters, drug dealers, and prison inmates. Tattooing has historically been a male dominated profession with a few female exceptions (particularly if we are speaking of the West), but the practice of tattoos has an elaborate history and goes back centuries, with some form of tattooing tradition found in nearly every culture around the globe.

The famous “Otzi the Ice Man”, who was discovered on the Otztal Alps between Austria and Italy in 1991, was confirmed the oldest and most well preserved body ever found. Otzi was dated at over 5000 years old and was found to be sporting an impressive 57 tattoos dispersed all over his body, speaking to how far back the practice of tattooing goes. For Pacific cultures, tattooing has had huge significance historically and ritualistically. Polynesian tattooing is considered the most intricate and skilled of the ancient world, as Polynesians believe that a person’s mana, their spiritual power or life force, is expressed through their tattoo. The Egyptians also highly valued tattooing, and elaborate tattoos have been found on mummified remains of ancient Egyptian priests and priestesses. Egyptians also had a huge impact in spreading the practice of tattooing throughout many parts of the world during its third and fourth dynasties.

Western culture was somewhat late to embrace tattoos as an acceptable cultural practice. Although the early Greeks and Romans dabbled with tattoos (having learned the practice from the Persians), as Christianity spread throughout the Roman Empire tattooing gradually fell out of favor. A slew of Popes forbade tattooing of any kind and the practice became virtually unknown for centuries. Surprisingly, one of the major resurgences of interest in tattoos in Europe occurred among 19th century high society Victorian women (as well as men), after British explorers encountered tattooed cultures on their voyages to the South Pacific and brought back the practice to Britain. Feminist art critic, Margot Miffin, in her fascinating book Bodies of Subversion: The Secret History of Women and Tattoos, explains how tattooing became an upper class social fad during the 19th century and gave women a way to subtly challenge prevailing Victorian ideals of feminine purity, as tattoos had long been associated with deviance in the West. Tattoos gave Victorian women an experience of power and self-ownership in a time when they had little sexual or political agency.

The tattoo craze grew during the 19th century, and even Winston Churchill’s mother had a tattoo of a snake eating its tail (the symbol of eternity) on her wrist. Queen Victoria was also believed to have had a tattoo of a Bengal tiger fighting a python. From Victorian Europe, the craze spread to America. In 1897, Miffin says that an estimated 75% of American society women were tattooed, usually in places that could be easily covered.

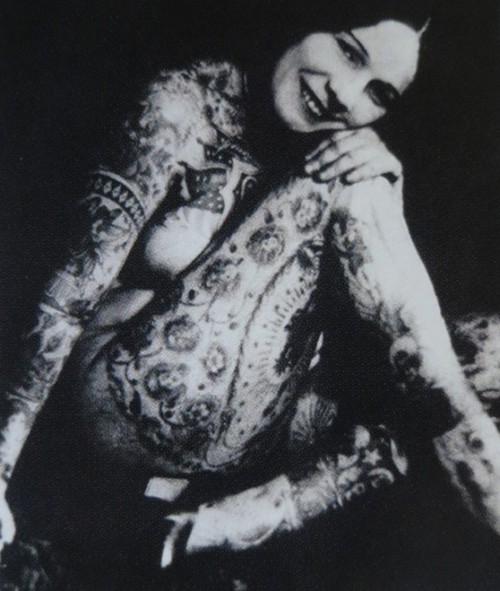

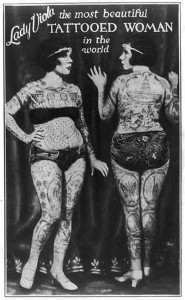

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries some of the first women appeared with tattoos covering their entire bodies, performing in freak shows and circus acts where women could make more money than men doing “flash shows”. These women were mostly of lower class who performed as a way to make a living. They submitted themselves to getting entire body suit tattoos that were done by hand needle by male tattooists (this was before the time of machine tattoo guns–ouch!). Some of these women felt oppressed and exploited by the experience, while others felt liberated and empowered by the chance to act outside of traditional feminine roles and occupations and continued modeling their tattoos even after retirement.

The Mark of Tattoos on the Feminist Sexual Revolution

For second wave feminists who chose to get inked, I imagine tattoos would have posed a useful double challenge to both Victorian notions of women’s sexual purity, as well as Freudian psychoanalytic notions of passive femininity, the latter of which had dominated cultural ideas about women’s sexuality in the post-war era. Despite the common contemporary misconception that second wave feminists were anti-sex, in reality sex was arguably the central pivot point on which second wave feminism turned. As Jane Gerhard points out in her illuminating book, Desiring Revolution: Second Wave Feminism and the Re-Writing of American Sexual Thought, a concern with re-inventing sexuality, claiming the female body as sexual agent, and freeing female sexuality from confined Freudian definitions of passive femininity was central to the political and personal agenda of second wave feminism. Ideas about what sexual liberation meant were incredibly diverse among second wave feminists, but tattoos could have easily been seen by many women of the time as a complimentary “accessory” to their goals of sexual revolution.

It was also during this time that women began entering the male dominated profession of tattooing, and opening their first tattoo shops. Where women in the West had historically been the models and muses of male tattoo artists, women were now taking up tattooing as a medium of creation and self-expression. Some of the earliest female tattooists offered to do tattoos free of charge on other women as an expression of solidarity.

Tattoos and the Paradox of Empowerment

Tattoos became increasingly accepted into mainstream culture in the 80s and 90s, as tattoo art became a way for women to express their inner lives and tell their stories on their bodies. Tattoo culture also underwent a distinct shift at this time as their popularity arose in parallel with the rise in cosmetic surgery and the mainstreaming of pornography in the 80s and 90s.

Marisa Kakoulas, a New York Lawyer and tattoo model speaks to the huge change she witnessed in tattoo culture from the 80s and 90s to the new millennium. She laments how tattoo magazines moved from their early focus on body art, where models of different ages, both male and female alike, exposed their body art in diverse ways to be photographed (these were the magazines I used to peruse in my teens), to what became a focus on a singular model of the “sexy woman” at the turn of the millennium. Tattoo magazines learned that they could sell more copies if they constantly featured sexy naked tattooed young women in the same suggestive poses on their covers. This was part of a much larger trend towards “sexiness” aimed at young women that was taking place in nearly every corner of the culture–from music videos to Halloween costumes. Thus, slowly, tattoo magazine culture shifted from focusing on the diversity of body art tattoos, to an increasingly narrow representation of one kind of sexy tattooed female body. The more tattoos became mainstream and fashionable, the more their original deviant erotic appeal became commodified and sold to the masses.

Despite the conflicted messages commodified tattoo culture is giving to young women today, I still believe in the power of tattoos as an empowering art form for women, if done consciously. I also need to say that choosing not to get a tattoo can be an equally empowering choice for a woman. The most common reasons cited by women for why they get tattoos are: a) to feel empowered, b) to feel sexy, c) to reclaim their body after sexual abuse, trauma, or cancer, d) to mark an important milestone in their life, e) to enact a form of rebellion. Tattoos are as diverse as the women who wear them, and they have the ability to uplift us as much as they do to degrade us. Looking back at my own journey with tattoos over the past 13 years, I would say that my own motivations for getting tattoos were a mix of all these themes at different points in my life.

It’s undeniable that I was influenced by the culture around me in my teens, and that a desire to be seen as sexy and rebellious played a role in my choice to start tattooing myself. I carried a genuine creative impulse in my desire for tattoos, but it was more immature and dis-embodied in my late teens; it was less connected to that fearless sense of self-possession and sexual agency that I had wanted to emulate in the tattoo models that I idolised. My relationship to tattoos gained more dimension and depth as I got older. My tattoos came to express more of my mature erotic and artistic side, and displayed my “rebellion” against conventional standards of feminine beauty that I had always felt confined by. I had never strongly identified with being feminine (even though I look quite feminine) or masculine in the conventional sense. Tattoos were my way of disrupting any comfortable gendered dichotomies or expectations the culture or others might impose on me. Despite the many mixed motivations that were involved for me from the beginning, tattoos have always been a way that I worked toward discovering my own personal power, a way I confronted and challenged gender assumptions in the culture around me, and a way that I uncovered my own erotic and spiritual depths, through trial and error.

From Butterflies to Black Fire: A Rite of Passage

From as early as I can remember my life journey has been marked by a fire walk through the dark side. I’ve written elsewhere about some of the traumas that impacted and fragmented the formation of my self-identity as a young child, and the unique and dangerous journey through madness and mysticism that I underwent in my twenties as a result. I’ve also written elsewhere about my relationship with the Liminal, which I define as an in-between space of darkness, ambiguity, and creativity, that has been central to my inspiration as an artist and to my identity as a nomadic traveler. Black Fire, my latest tattoo, represents, for me the unique soul print I carry as a result of this precarious and difficult path I’ve taken through the dark side in this lifetime, and the untamable creativity that has emerged in my life as a result of that crucible.

The tattoo also marks a major milestone and turning point in my life, and I experienced the process of getting it as a ritualistic rite of passage. Perhaps also part of turning 30 this year. Over an eight hour period of getting the tattoo, where I endured a lot of physical pain at different points, I found myself spontaneously entering into different forms of meditation. Sometimes I would fall into a natural rhythm of matching my breath with the breath of my tattoo artist for hours; my mind completely peaceful and emptied of all content. At other times, painful memories, images, emotions, and body traumas came to the surface. Many uncomfortable energies of pain, anger, fear, loss, disappointment, and resentment that I’d held onto subtly and unconsciously for years in my body rose to the surface to be felt. I experienced some of these energies as very visceral, ancient, and preverbal; as if I had descended into the underworld where symbols and words no longer made sense to my conscious mind. As feelings, images, and memories surfaced, I found myself spontaneously inviting them into my heart, filling them with light, and then releasing them with love on my out breath, without trying to make any story about them. The experience was very deep and guttural, and intensely painful. I had to be with the pain fully, in tandem with the physical pain of getting the tattoo, and release the emotional energy on its own terms through a state of surrender and without a story. It was a kind of surrender to love that is as evicerating as it is liberating.

Despite the deeply personal processing I was undergoing, I also found the experience of getting my tattoo incredibly relational. My tattoo artist and I co-designed the piece together, and we worked out the lines literally as he was drawing them on my body. I experienced the artistic process as much more intimate and co-creative than tattoos I’ve gotten in Canada, but that may have also been a result of the scale of the tattoo itself. The design pattern was abstract and emergent and had to be strategically wrapped around my body at every step, so it required a lot of team work to execute well.

Close to the end of the healing process of the tattoo, my energy started to feel more focused and channeled. I’ve always been a very creatively charged person, but I started to feel a bit like lightening, literally. Most importantly, I felt like channeled lightening, with less like scattered energy and attention. Certain distractions and negative thought patterns naturally became dimmer and fell to the background, and certain difficult decisions and boundaries I had needed to make in my life for a long time I finally started to make. By the time the month of healing for my tattoo was over, I felt subtly but distinctly different. I felt stronger and humbler, more embodied and more fiercely committed to my own voice and creative fire. I experienced more spaciousness from the holds of my past and more intimacy in my own skin in the present. I felt the tattoo itself had taken my life journey and my crucible through the dark side and transformed it into a unique meditation; an expression of beauty and strength that would be forever displayed on my body.

The Evolving Culture of Tattoos

Despite the ancient practice of tattooing, the culture surrounding tattoos is ever evolving and innovating. This past month, I was able to attend a tattoo convention in Kathmandu featuring tattoo artists from around the world who were showcasing their work as part of a public exhibition. Every country had a stand set up at the convention with tattooists from each country tattooing people live, as well as showcasing photographs of their past work. It was an amazing opportunity to see the innovations in technique, color, and quality of tattoos that have occurred over the past decade, and to contrast the different art forms that were favoured in different countries and cultures. I found myself most drawn to the artwork coming out of Japan, Nepal, and Thailand, which tended to be much more intricate work with a lot more abstract designs crafted seamlessly with the contours of the body. I found most of the tattoo art coming out of the U.S and UK to be quite pictoral and blunt (like hanging a picture on someone’s body), whereas the Asian art was much more “in movement” and in tune with the body’s natural lines. I was also impressed to see that for every country in attendance at the convention there was an equal number of female tattoo artists as men.

Perhaps interesting to note is that modern interpretations of tribal-like pattern designs (like the one I got in Nepal) are starting to become more popular in the West as well. More women are starting to opt for large scale tattoos rather than small flowers or butterflies, the latter of which have been the most popular among women in the recent past. In our modern Western culture where the importance of ritual practices and sacred rites of passage for girls have been downplayed or forgotten, it is perhaps unsurprising that a resurgent interest in tribal-like tattoo patterns– patterns that give a modern flare to the ancient themes of our ancestors–is coming increasingly into vogue.

Tattoo culture will continue to evolve in the years to come, and women’s unique place in tattoo culture will likely continue to transform. The most important advice I would give to a young woman (or anyone) who is considering getting a tattoo is to really do your research. Equip yourself with deep knowledge about tattoos and what is involved in getting one. Make sure you go to places that are safe and clean; and most importantly, really think about why you are getting a tattoo and what it means to you. Statistics show that women have a higher percentage rate of tattoo regret later in life than men do. So if you are getting a tattoo just to be cool, it is more likely you will regret it later. Understanding our own personal motivations as best we can, as well as knowing the historical, social, political, and spiritual dimensions that intersect at the site of tattoos on women’s bodies, will hopefully support new generations of woman to make more empowered choices when it comes to getting (or not getting) a tattoo for themselves.