The following is excerpted from The Magical Universe of William S. Burroughs, forthcoming from Mandrake of Oxford, Autumn 2014.

With regard to the infamous English occultist Aleister Crowley (1875-1947), William S. Burroughs certainly had an intermittent awareness of – and recurring interest in – the man who had styled himself To Mega Therion, “The Great Beast 666”, and been dubbed by the popular press of his day “The Wickedest Man in the World” and “The Man We’d Like To Hang.” As early as 1959, the fact that Burroughs had been profiled in Life magazine, after the publication of Naked Lunch by The Olympia Press in Paris, was the cause of a pained exchange with his outraged mother, Laura Lee Burroughs, in which Burroughs compares himself with the former “Wickedest Man in the World.”

After taking up his “second career” in the visual arts in the late 1980s, Burroughs even went so far as to title one of his abstract “spirit paintings” in 1988, Portrait of Aleister Crowley. Numerous occasional references crop up in interviews and throughout his fiction down the years, even if they are not always consistent – but to be fair, as self-styled Magus, occultist extraordinaire, and Prophet of a New Aeon, Crowley himself was a complex and not always consistent figure, and so any attempt at commentary is bound to be prone to similar complications . . .

As late as 1996, a phone interview with Burroughs by Robbie Conal and Tom Christie included the following exchange:

Interviewers: You’re interested in the occult, aren’t you?

Burroughs: Certainly. I’m interested in the golden dawn [sic], Aleister Crowley, all the astrological aspects.

Back in the mid-1970s, when Burroughs was introduced to Led Zeppelin guitarist Jimmy Page in New York, to record an “interview” for Crawdaddy magazine, to break the ice they discussed mutual friends and acquaintances back in London:

Burroughs thought he and Jimmy might know people in common since Burroughs had lived in London for most of the past ten years. It turned out to be an interesting list, including film director Donald Cammell, who worked on the great Performance; John Michell, an expert on occult matters, especially Stonehenge and UFOs; Mick Jagger and other British rock stars; and Kenneth Anger, auteur of Lucifer Rising . . .

After an initial correspondence, the writer Graham Masterton had become friends with Burroughs when he was working as an assistant editor to the newly founded “men’s magazine”, Mayfair, which had enabled him to commission a series of articles, The Burroughs Academy. As these has focused on a number of the author’s more “counter-cultural” interests, when Masterton agreed to an email exchange about his friendship with Burroughs in London in the 1960s, I was especially mindful to ask him as carefully as possible about this particular milieu:

MS: What William described as “the Magical Universe” is a recurring theme throughout his life & work, despite the efforts of some to deny it (or at least relegate it to a sort of eccentric footnote.) The Sixties were clearly a time when people were open like never before to all sorts of new thinking and re-examination of older ideas, including magic, mysticism, and non-Western beliefs. Brion & William had been exposed to folk-magic in Morocco, and in London they knew the likes of Kenneth Anger – Donald Cammell – Anita Pallenberg – Jimmy Page – who all had more than a passing interest in Aleister Crowley, ritual magic(k), and witchcraft; also the recently published letters favourably describe visits to ‘psychic healers’ like Major Bruce MacManaway. What impression did you get (if any) of his interest or involvement in such things?

GM: We talked a great deal about the supernatural and particularly about near-death experiences and hallucinations and whether there was any kind of life after death. I always got the impression that he believed the human mind was capable of far more than we realize (which was one of the reasons he was so interested in Scientology and Wilhelm Reich’s “orgone box” and such things) and that we all have what you might describe as a soul. But he saw it from a scientific rather than a religious perspective.

In an interview recorded some years later – after William had died, in fact – his former assistant, companion and manager (and now legal heir and literary executor), James Grauerholz, introduced a note of playful ambiguity:

. . . Burroughs considered Crowley a bit of a figure of fun, referring to him as “The Greeeaaaaaat BEEEEAST!” in that behind-closed-doors, queeny comic delivery he used sometimes: his voice rising straight up in pitch, into an hysterical falsetto . . .

But also evinced a certain lack of correct information, surprisingly, when he went on to say:

William knew quite a bit about Crowley’s life and work, and he certainly dug deep into the Necronomicon (anonymous but often attributed to Crowley) when it became available in a snazzy, black-morocco, tooled-leather hardback binding. He appreciated much about Aleister Crowley.

The Necronomicon, in fact, is an entirely fictitious work – created by “Weird Tales” author, H. P. Lovecraft, as the ultimate “damned book” or grimoire of occult blasphemies – in effect, the bible of his existentialist science fiction horror stories, the Cthulhu Mythos. Although a number of tribute or even spoof “Necronomicons” have been created as a sort of homage to Lovecraft and his works – and it is certainly true that a number of contemporary occult practitioners have experimented with this material, in an exercise of extended Post-Modern play-acting, including one-time apprentice and secretary to Crowley, Kenneth Grant – there is no evidence that Crowley had even so much as heard of Lovecraft and his fictitious grimoire, yet alone had anything to do with it (the best efforts of conspiracy theorists, esoteric scholars, and occult pranksters notwithstanding!)

Burroughs also had a recurring tendency to equate the most (in)famous dictum of “The Great Beast” with the alleged “Last Words” of the legendary Old Man of the Mountain and Master of the Assassins:

Old Aleister Crowley, plagiarizing from Hassan I Sabbah, said: “ ‘Do what thou wilt’ is the whole of the Law” . . . And then Hassan’s last words were “nothing is true; everything is permitted.” In other words, everything is permitted because nothing is true. If you see everything as an illusion, then everything is permitted . . .

The English graphic artist, Malcolm Mc Neill, first met Burroughs in London in 1970, when he embarked on what would turn into a lengthy collaboration with him, ultimately intended to be a pioneering new form of book, combining artwork and text, Ah Pook Is Here – which has never appeared in its intended form, sadly, despite seven years of on-and-off collaboration, and several hundred pages combining Mc Neill’s original images with Burroughs’ text. The spirits of Crowley and Sabbah hover around an amusing anecdote related by Mc Neill in his memoir, Observed While Falling, which concerns the Middle Aged Writer proposing a very different and particular kind of “collaboration” to the Young Artist:

On the evening in question, after lighting up his umpteenth [cigarette], he suddenly switched to a conspiratorial tone.

“So Ma-a-a-alcolm . . . the Old Man of the Mountain says, ‘Do as thou wilt shall be the whole of the law.’”

“Yes, Bill . . .”

“So why don’t we, then? We’ve known each other a while now.”

By then his left hand had made its way to my side of the table. Kind of like a crab, I thought. My knees came together. It occurred to me we were in a steakhouse, and suddenly a whole lot was at stake.

“Well, Bill,” I said, “I guess I’ll wilt.”

“I was forgetting – you like gi-i-i-i-i-rls.”

We finished the meal as if nothing had happened . . .

By the mid-1970s, Mc Neill had followed Burroughs from London to New York, in the hope of completing the Ah Pook project, and when Burroughs vacated his Franklin Street apartment in 1976 to move to the now infamous “Bunker” on the Bowery, he offered the lease to Mc Neill, leaving behind a rocking chair and an old freestanding wardrobe. Before long, Mc Neill could sense something in the flat, prompting him to ask Burroughs if he had ever “seen anything unusual” while he had been living there:

“Like what?” he asked.

“Smudges,” I said. “Sometimes I see black smudges out of the corner of my eye.”

“Whereabouts exactly?”

“By the door. Near the wardrobe.”

“Hmmm . . . that would make sense,” he said.

Returning home, Mc Neill immediately examined the wardrobe in question from all sides, eventually standing on a chair to look on top:

There I discovered a small note in Bill’s handwriting. Two dried up lemon slices were alongside and it was sprinkled with salt. It was a curse, the ‘Curse of the Blinding Worm’ to be exact, one of the many he’d recited to me back in London. They’d been taught to him . . . when he was a child, he’d said. Beneath the note was a newspaper clipping – an unflattering review of Exterminator! by Anatole Broyard.

This was not so much a case of “life imitating art,” perhaps, as art with a magical intention attempting to initiate events in everyday life. Mc Neill later observed:

The fact that the loft nearly burned down soon after the discovery of the note, was an added factor that confirmed Burroughs’ other remark in the Morgan bio, that sometimes a curse can “bounce back and bounce back double.” Though he didn’t say so – cursing amounts to dialogue.

The spirit of Aleister Crowley even gets a walk-on part, indirectly-speaking at least, in The Place of Dead Roads:

Tom introduces Kim to Chris Cullpepper, a wealthy, languid young man of exotic tastes. He is into magic and has studied with Aleister Crowley and the Golden Dawn. They decide on a preliminary evocation of Humwawa, Lord of Abominations, to assess the strength and disposition of enemy forces . . .

The scenes of ritual magic which occur subsequently are clearly influenced more by Chaos Magic and Freestyle Shamanism, however, than the more formal Ceremonial Magic of Crowley or the Golden Dawn, for all the inclusion of “barbarous names of evocation” and use of sex as a means of raising energies:

Chris has set up a stone altar in the old gymnasium with candles and incense burners, a crystal skull, a phallic doll carved from a mandrake root, and a shrunken head from Ecuador.

Kim leans forward and Marbles rubs the unguent up him with a slow circular twist as Chris begins the evocation . . .

UTUL XUL

“We are the children of the underworld, the bitter venom of the gods.”

. . . Tom is changing into Mountfaucon, a tail sprouting from his spine, sharp fox face and the musky reek.

Kim feels something stir and stretch in his head as horns sprout . . . a blaze of silver light flares out from his eyes in a flash that blows out the candles on the altar. The crystal skull lights up with lambent blue fire, the shrunken head gasps out a putrid spicy breath, the mandrake screams

IA KINGU IA LELAL IA AXAAAAAAAAA

A somewhat bizarre illustration of the interconnectedness of all of Burroughs’ creativity – writing, thinking, and, increasingly latterly, painting – also how his continuing belief in “The Magical Universe” is a central and unifying factor, is a startling admission concerning “Humwawa” in an interview ostensibly about his visual art:

I’ve got a real muse thing going. Some of my paintings are directly influenced by them – and I don’t mean the standard nine muses either. I like to invoke all sorts of muses, like Humwawa, Lord of Abominations! His head is a mass of reeking entrails. He arrives on a whispering south wind, with his brother Pazuzu, Lord of Fevers and Plagues. They come in on a whispering, fetid south wind.

This is another example illustrative of the kind of “creative confabulation” that can occur for a number of reasons where issues of art, creative imagination, and the occult intersect. The most common reason simply being misunderstanding or misremembering where arcane or esoteric material is concerned – a secondary reason being an unintentional and perhaps unrealised error of recall (especially when factors such as heavy and habitual use of alcohol and drugs are concerned) – and, thirdly, perhaps a more intentional conflation of ideas for artistic, creative, or even occult reasons, such as might occur in play with “conspiracy theory” style thinking for satirical effect.

Of the aforementioned “spoof Necronomicons” created by fans and fellow horror writers dabbling in occult themes alike, the most successful and well-known must surely be the so-called “Simon Necronomicon” (thus called because the only authorial attribution is to an alleged editor and translator, “Simon”), which first appeared in 1977. Described with some affection by Social Historian, Professor Owen Davies, as a “well-constructed hoax” the book – which appears most likely to have originated in the occult circles around Herman Slater’s Magickal Childe bookshop in New York – of course claims to be the authentic “dark grimoire of forbidden lore” referenced by Lovecraft and his literary followers, but it is in fact nothing of the sort. Rather, the material contained within the book draws mainly on Ancient Middle-and-Near Eastern Mythologies such as the Assyrian, Babylonian, Chaldaean, and Sumerian, with just enough allusions to the works of both H. P. Lovecraft and Aleister Crowley woven in to try and establish a plausible connection (at least, if you don’t question some of the apparent reasoning too rigorously . . .) The book clearly caught something of the zeitgeist: after the initial, limited edition “Schlangenkraft, Inc.” imprint Sold Out, it was bought by a mainstream publisher, and has not been out of print since.

One of the more curious coincidences, at least as far as we are concerned (although I can almost hear the ghost of William S. Burroughs moaning “There are no coincidences . . .”) is that when the first edition of the Simon Necronomicon came out, it bore the perhaps somewhat surprising endorsement:

“Let the secrets of the ages be revealed. The publication of the Necronomicon may well be a landmark in the liberation of the human spirit.” – William S. Burroughs

Varying versions of how this might have come about have been put forward: one suggested by occult author Peter Levenda – who many consider to be in fact the most likely candidate for “Simon” – being that Burroughs simply used the same publisher as whoever it was behind Schlangenkraft, Inc., and that when he saw the Necronomicon being printed there remarked it was “a dangerous book . . . the theological equivalent to a loaded gun.” The book’s illustrator, Khem Caigan – who had also assisted “American Magus” Harry Smith in an attempt at compiling a concordance of the so-called Language of the Angels, Enochian, as recorded by Elizabethan sorcerer-scholar John Dee and “The Great Beast” Aleister Crowley – has given an equally plausible and down-to-earth explanation:

It was about that time that William Burroughs dropped by, having caught wind of a “Necronomicon” in the neighbourhood. After going through the pages and a few lines of powder, he offered the comment that it was “good shit.” He might have meant the manuscript too . . .

Whatever the truth of the matter, it is interesting to note that Burroughs incorporates references to “Humwawa” and “Pazuzu” into his Magical Universe – perhaps most famously in the Invocation at the start of Cities of the Red Night, which also includes a mention of “Kutulu, the Sleeping Serpent who cannot be summoned.” Humwawa and Pazuzu, brother-demons from Ancient Mesopotamian mythology, who are both monstrous, chimaeric entities associated with fevers, plagues, and storms, do not appear anywhere in the fiction of H. P. Lovecraft – but they do both feature heavily in the Necronomicon put together by “Simon” for Schlangenkraft, Inc. Likewise, the reference to “Kutulu” is probably derived from the same source, wherein the variant spelling of the originally Sumerian “Kutu” (meaning “underworld”) has been made, doubtless to suggest some equivalency to the central embodiment of evil in Lovecraft’s nightmarish mythos, Cthulhu.

America is not a young land: it is old and dirty and evil before the settlers, before the Indians. The evil is there waiting . . . – William S. Burroughs, Naked Lunch.

After his return to the United States in 1974, Burroughs began to re-engage with more traditional styles of writing such as the picaresque, as a way of combatting the writer’s block that he felt was a dead-end almost inevitably brought about by his over-zealous commitment to non-linear, non-narrative – and even non-literary – experimentation. Using the tentative return to episodic, magical realist-style narrative that had characterised works such as The Wild Boys and Port of Saints, Burroughs began to work on what would eventually become his “comeback” novel, Cities of the Red Night, which would also be the first volume of his last great trilogy.

In June 1976, Burroughs moved into what had been the locker-room of a former YMCA at 222 Bowery – a large, bare, almost windowless space of concrete walls, floor, and ceiling, which became known affectionately as “The Bunker.” Described by Victor Bockris as a “totally white, starkly lit cavern”287 it was in the middle of a rundown area of bums and junkies in New York’s Lower East Side, but the three locked gates and bulletproof metal door between Burroughs and the street were enough to make him feel secure. Apart from its security, The Bunker had other attractions, which Burroughs, as ever, would ‘borrow’ for a setting in The Place of Dead Roads:

More advanced and detailed incantations are carried out in the locker-room gymnasium of an empty school . . . “All that young male energy, so much better than a church my dead I mean my dear, all those whining snivelling prayers . . .”

There was also the fact that Burroughs and some of his friends and visitors felt the place to be haunted, which doubtless prompted a number of his discussions at that time regarding ghosts and incubi and succubi, as well as various psychic experiments. As he would write in explanation regarding Fear and the Monkey, one of the very few of his texts that Burroughs identified as a poem, which revisits a number of familiar literary preoccupations:

August 1978

This text arranged in my New York loft, which is the converted locker room of an old YMCA. Guests have reported the presence of a ghost boy. So this is a Oui-Ja board poem taken from Dumb Instruments, a book of poems by Denton Welch, and spells an invocations from the Necronomicon, a highly secret magical text released in paperback. There is a pinch of Rimbaud, a dash of St.-John Perse, an oblique reference to Toby Tyler with the Circus, and the death of his pet monkey.

FEAR AND THE MONKEY

Turgid itch and the perfume of death

On a whispering south wind

A smell of abyss and of nothingness

Dark Angel of the wanderers howls through the loft . . .

Ever since his youth William Burroughs had been intrigued by magic and the occult, reading the Egyptian and Tibetan Books of the Dead and Eliphas Levi’s History of Magic while he was at Harvard. Evidently, with his return from the Old World to the New, he had not left such interests behind. In 2007, Malcolm Mc Neill visited Ohio State University Archives to examine correspondence between himself and Burroughs in connection with Ah Pook Is Here, and later wrote:

Most of the material in the box was familiar to me, but amongst the paperwork, I found one folder entitled “WSB Desk Scraps” that turned out to be especially enlightening. It was described as a collection of “newspaper clippings and odds and ends” that Bill had brought over from London. Amongst his little hoard of photos, bon mots, and aphorisms were several catalogues, business cards, and flyers from theosophist, spiritualist, and occult societies. Otherworldly reference he’d considered important enough to bring with him across the Atlantic.

Even towards the end of his life, William S. Burroughs’ engagement with The Magical Universe did not wane. The magical, psychic, spiritual and occult appear in his later fiction like never before, from depictions of astral travel and “sex in the Second State” to descriptions of actual rituals, referencing everything from Aleister Crowley and The Golden Dawn, to the Myths of Ancient Egypt, and even the dreaded, mythical Necronomicon of H. P. Lovecraft, as the Invocation to Cities of the Red Night showed:

This book is dedicated to the Ancient Ones, to the Lord of Abominations, Humwawa, whose face is a mass of entrails, whose breath is the stench of dung and the perfume of death, Dark Angel of all that is excreted and sours, Lord of Decay, Lord of the Future, who rides on a whispering south wind, to Pazuzu, Lord of Fevers and Plagues, Dark Angel of the Four Winds with rotting genitals from which he howls through sharpened teeth over stricken cities, to Kutulu, the Sleeping Serpent who cannot be summoned . . .

All of this was interwoven with increasingly neo-pagan concerns for the Environment, the impact on Man and Nature of the Industrial Revolution with its emphasis on “quantity, not quality” and standardisation – as well as perceived turning points in History. His adoption of the Ancient Egyptian model of the Seven Souls, continuing development of a very personalised myth of Hassan-i Sabbāh and the Assassins of Alamut, and resistance to Christianity (“the worst disaster that ever occurred on a disaster-prone planet . . . virulent spiritual poison . . .”) made him of increasing interest and relevance to the new occultists who were emerging from successive generations of counter-culture that Burroughs had helped to shape through the example of his life and work.

In the early 1990s, the elderly Burroughs was initiated into the Illuminates of Thanateros, the leading Chaos Magic group, which had been founded in the late 1970s by pioneering English occultists, Peter J. Carroll and Ray Sherwin. Perhaps this was not such a surprising development. Many Chaos Magicians clearly felt a debt to Burroughs and his peers, and shared many of the same concerns as Thee Temple ov Psychick Youth: demystifying magic, yet at the same time distilling the best from Aleister Crowley and Austin Osman Spare, while taking advantage of the latest ideas emerging in computers, maths, physics and psychology. With the experiments started at The Beat Hotel, that he then took out onto the streets of London, Paris, and New York, William S. Burroughs was recognised as a definite pioneer and precursor: and with the later connections established through a younger generation of artist-occultists, the link from “cosmonaut of inner space” to “psychonaut” was assured.

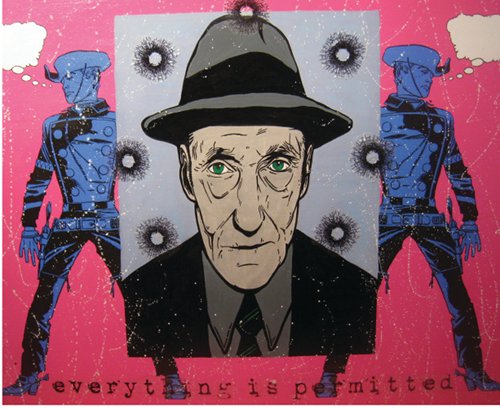

Artwork: “Everything is Permitted” by Billy Chainsaw, used by permission of the artist.