The following is excerpted from Raw Chi: Balancing the Raw Food Diet with Chinese Herbs by Rehmannia Dean Thomas, published by Evolver Editions/North Atlantic Books.

In Eastern ideology, evolution is thought to progress in a series of spirals, each one rising slightly higher than the one before it, resembling a spring from which new life can emerge.

Ancient Chinese men and women looked upon nature from their hillside caves and saw cycles of hot/dry and cold/wet. They saw night and day, that the sun progressed through longer and shorter days, creating seasons that led back to each other. They came to recognize a dynamic balancing act of two opposing forces that governed life as we know it, two polarities held in a dynamic equilibrium. Life appeared to sit delicately upon the crux of an energetic seesaw between these two extremes. These wise men and women concluded that all forces of life must be held within the balance of this dynamic equipoise. If one extreme overpowered or disabled the other, and/or the opposing energies split apart, all life would end.

These ancient people drew a diagram in which two teardrops swim around each other within a circle. The teardrops are equal in size and shape. One represents exertion, thrust, heat, and day, the other, rest, night, coolness, wetness. One teardrop represented the time when the heat came, the fruits and tubers grew sweet, and the canopy of green cast cooling shade over the people’s huts. The days were long, and the people arose earlier and hunted longer. During the time symbolized by the other teardrop, the days were shorter, and the people rested longer in their caves. They stayed out of the bitter cold and hunted less. The white snows came, and the once tufty trees in the forest dropped their leaves and stood naked, their skeletal arms reaching up in search of the sun. The white winds blew, and everything seemed to retreat to shiver in nooks and crannies. The people wondered if it all had died. How could anything live out there?

But the warm breezes came again, and the trees sprouted their green tufts. Everything returned as it had been before, when the animals, fruits, and herbs were plentiful. Everything hadn’t died after all! Life, death, and new life followed each other in cycles. The drawing of the two teardrops explained these cycles for the people of the mountain. They made a very important observation, one that forms the cornerstone for understanding the dynamic of chi and of all life. But this drawing didn’t represent the complete picture; something was missing.

The ancient people continued to observe nature’s cycles of growth, decay, and regrowth. They came to understand that energy didn’t only manifest as opposing forces in a constant tug of war; this was too extreme. There had to be a little of the opposite energy within each teardrop for the whole to maintain balance. When the cold, white winds came, and the leaves withered and fell, the forest didn’t die in the process. Perhaps a small pilot light of life still burned within, so that the next season could begin. The dormant period of rest and stasis—which these people called yin—contained within it the seed of yang, waiting to initiate the next growing season. These insightful people saw that when the hot days came and the forest was full, they needed a few cool rains and cool nights, or everything would become too dry and fires would burn in the forest. The yang period of warmth and acceleration needed to have that little yin balance, or it would consume itself.

The ancients then examined their own patterns and survival needs and found that on hot days, they needed to take more water on their hunting and gathering treks; they needed to stop and rest a while in the shade. On the cold, white days, they needed to kindle the fire hearth for warmth. When they slept at night, they didn’t die; a little pitter-patter was still going on in their chests.

Thus, these early people of the mountains of northern China drew two little dots of the opposite color within the two larger teardrops, describing life. Yin and yang were held in perfect equipoise via these two little dots; these nuclei generated the cyclical flow of yin and yang. In this way, the fires wouldn’t come, and the white winds would eventually recede. Life would thrive and transform itself into new life.

The symbol of yin and yang became the foundation of Chinese health philosophy. The ancients had realized a truth, that by keeping these forces in balance, chi would remain vibrant. Conversely, when the balance of yin and yang is upset, chi may stagnate or consume itself. These are the mechanisms of illness and disease. During yin time, what if the white winds remained too long? The pilot light might be extinguished, and new life might not be triggered. In the yang time, what if the rains and cool nights didn’t come? Fires might start and consume everything. Thus, yin and yang must balance each other for life to thrive. The same is true in the microcosm of our bodies. The flame of metabolism must be fanned, and the wellspring of our future must be filled. When these are held in balance, we enjoy the gift of health.

The Five Organ Meridians

By approximately 1500 BC, the Chinese had developed a surprisingly accurate understanding of human physiology and metabolism, including reproductive and neurological endocrinology. They perceived the body as containing five primary organ systems that must work in harmonious interaction for health to be maintained. These functional networks contain yin and yang organ meridians and other components—the heart, liver, lung, kidney, and spleen meridians. We will briefly look at these organ systems and their primary times of dominance so that we can better understand the functions of the two primary organ/gland systems that “govern” chi within the milieu intérieur* of the human body: the lung (gathering chi) system and the spleen (nutritive chi) system.

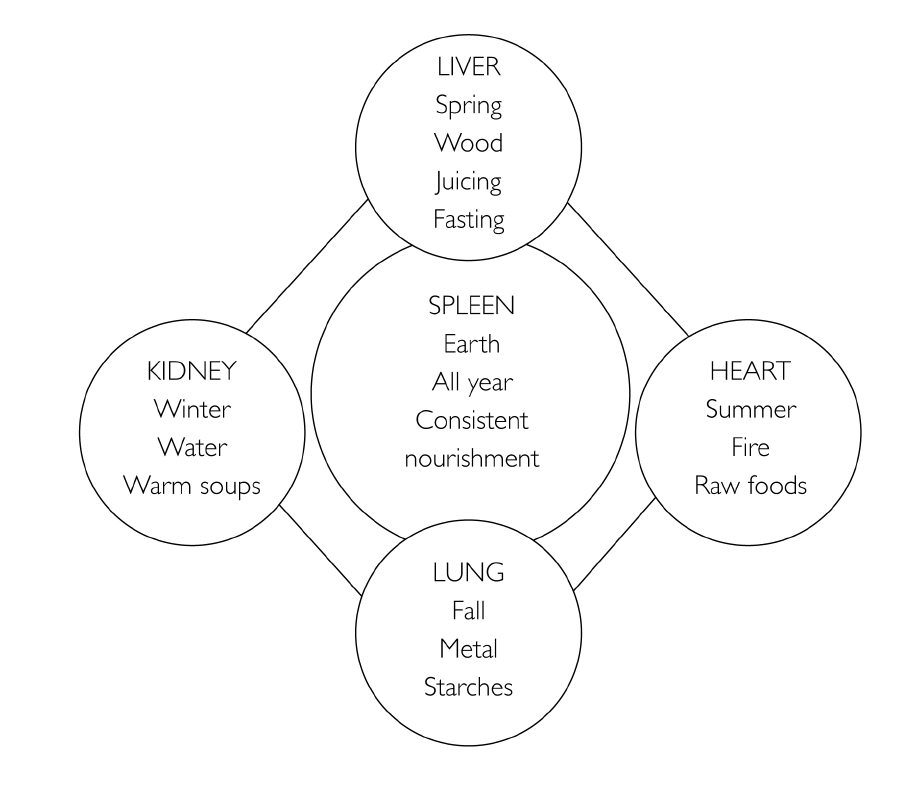

The ancient Chinese health mendicants drew a diagram of the four organ systems that they referred to as interdependent functional “meridians” on the north, south, east, and west perimeters, with the spleen meridian occupying a position in the middle. This was their way of associating the spleen meridian with the element earth, which is in the center of our cosmology. The four seasons are associated with four of the five organ systems, but the spleen system is not linked to any particular season. This is because it is seen as requiring “tonification,” consistent support, throughout the year.

The spleen meridian includes the stomach, spleen, pancreas, duodenum, and small intestine. These organs and glands comprise a functional unit that governs our metabolism.

The other four organ systems are dominant during certain times of the day and the year. For instance, spring begins with the liver meridian, which includes the gallbladder. In spring we need to cleanse the blood and liver by fasting on clean water and the juices of fresh, raw vegetables and grasses. We can lose a little weight during this time and take cleansing, herbal tonics to help remove unwanted yeasts and other microbes from the bloodstream. In Chinese ideology, the liver is associated with the element wood. The liver is dominant during the late night hours, 1–3 a.m.

In summer we must take care of our heart, as the hot weather is upon us, and we can get heated inside. This is the period when the cooling vegetables of summer ripen, and our diet may be comfortably raw. The heart meridian includes the pericardium and the arterial and vascular network and is associated with the element fire. The heart meridian is dominant during the hottest time of day: 11 a.m.–1 p.m.

During fall the Chinese say we must protect our lungs from the cooler, drier fall winds that kick up carcinogenic dusts. This is the time to carry a scarf and tie it around your nose and mouth while riding your bike! Our root vegetables ripen; our starchy foods—potatoes, squash, and onions—are ready for consumption. We can take herbal teas that include magnolia bud, licorice root, and cordyceps. These foods help warm our bodies and can aid in adding a little extra cellulose padding as we prepare for winter. The lung meridian is comprised of the lung and large intestine.

Starchy vegetables should be carefully cooked, as the starches are not easily digestible in their raw state; they are best “gelatinized” or lightly roasted for easier assimilation into the body. At this time we should modify our raw diet and allow a few cooked starches into our meals. The lung meridian is associated with the element metal and is dominant from 3 a.m.–5 a.m.

Winter is dominated by the kidney meridian, which includes the adrenals. We sleep longer, stay inside by the fire, and nurture ourselves so that we can restore our adrenals. We want to drink hot, soothing drinks and take our proteins in the form of soups and stocks. Lentil soup, barley and minestrone soup, oatmeal, dhal, miso soup, black bean soup, etc., are beneficial during this time, as are lightly steamed winter vegetables like pumpkin and squash. You can let yourself gain a few pounds, because you’re going to fast or cleanse when the spring comes. Drink hot tea during this time and take elixirs that include kidney-tonifying herbs such as ho shou wu, schizandra, goji, and rehmannia glutinosa (prepared). Kidneyessence is associated with the element water. The kidneys are dominant during the hours 5–7 p.m.

As mentioned, the spleen meridian is the governor of chi. This is where old blood is stripped down and some of the body’s new blood is built. While traveling through the other organs and glands of the spleen system, blood attains the vital freshness to hold and carry chi. Of course, all five organ systems work in tandem to maintain a healthy body, and there are confounding details in attempting to fully explain blood physiology. The liver, kidneys, and bone marrow are all involved in blood maintenance, so let us look briefly into the sojourn of chi through the body before further examining the physiology of the spleen meridian. There we will hopefully gain clarity on why the Chinese believe this organ meridian is specific to the production of chi.

*A term coined by French Physician Claude Bernard (1813–1878) while studying the beneficial role of probiotic bacteria in the human digestive system.

Image by Harry Ko, courtesy of Creative Commons licensing.