This article is excerpted from “The Initiatory Path in Fairy Tales: The Alchemical Secrets of Mother Goose” by Bernard Roger, published by Inner Traditions.

In the etymological and true sense of the word, initiation means “to put on a path, to introduce someone into a way.”[1] It involves a dynamic projection starting from an initially static position.

The origin of initiation is one with that of the existence of humanity, as it is with the birth of each of its representatives. With respect to these latter, the first initiator is the mother when she expels the fetus that forms part of her body and projects the child into the world, where it will grow and become an individual.

With respect to humanity, myths on the one hand and the scientific hypotheses concerning the emergence of the human race on the other offer their own versions. In the Western world, the most widespread myths concern the “original fall” among monotheists, whereas the polytheism of antiquity evoked the interventions of Prometheus and Pandora in man’s fate. When one refers to the contemporary evolutionary model, it seems that the humanization of certain creatures of the animal kingdom was not unconnected with the acquisition of the mastery of fire by these creatures, coinciding with a selection from within this kingdom.

Was it through his “initiation” to the art of fire that man was able to extract himself from the womb of nature? The “first man” of the religions of the Bible would have allegedly lived in blessed ignorance if it were not for the intervention of the woman, who, inspired by the “adversary,” made him eat the forbidden fruit. “‘Behold, the man has become like one of us by knowledge of good and evil,’ the Creator then said. ‘Now, he must not stretch forth his hand to take also from the Tree of Life, so that he might eat its fruit and live forever.’ And Yahweh drove him from Eden to work the ground from which he had been taken,” and posted at the garden’s gate in order to forbid entrance, “the cherubim and the flame of the turning sword.”

On the other hand, the story of Prometheus, to which that of Pandora gave the finishing touch, tells how the fire guarded so jealously by the King of Heaven was stolen for mankind by the one who had created them with his own hands. Pandora, whose name can be translated as “the gift of all” and as “she who gives all,” was the creation of Hephaistos, who crafted her from clay. She was sent by the gods to humanity, which was then living in the tranquil bliss of the golden age. She gifted them with trials and tribulations that spread over the entire world once her mysterious box had been opened. In its depths, still hidden, was the invisible light of discreet Hope.

Here the myths are eloquent. At humanity’s origin—meaning at the starting point of the initiation of individuals summoned to leave the state in which nature had set them to take the path of becoming human beings—we find in direct relationship with the process of separation, whose principal agent is fire in all its demonstrative forms,[2] the transgression of a law. This transgression, according to the Bible, is responsible for the fall into matter; in pagan myth it brought about the end of the golden age.

Here we find man sent off on the path of mental development; he must start to “work the ground from which he had been taken.” This is a necessarily ambiguous path as it is based on—to use the expression from the sacred text—the “knowledge of good and evil.” We know today how it gave man, among other powers, the ability to destroy the fruit of billions of years of evolution in an instant or, if he chooses, to transform life on the planet into a waking nightmare.

Yet there is good reason why the contemporary scientist Carl Sagan defined humans as “star stuff,” and why an anonymous philosopher, who two centuries ago dedicated his work “to virgin, unsoiled Nature,” thought to describe himself as “a mote of dust from paradise.” Each of these individuals acknowledged, in his own way, the luminous origins of human nature.

Upon his arrival on the moon, where Cyrano de Bergerac fell by good fortune, he says that without a certain secret he would “have been killed a thousand times over.” By the Tree of Life growing at the center of the Garden of Eden, he tells the story of his encounter in a “forest of myrtle and jasmines” with the prophet Elijah, who entrusts him with this secret about the Tree of Knowledge.

Its fruit is covered with a skin that produces ignorance in whoever eats it, and it is beneath this skin that the spiritual virtues of this fruit of knowledge are contained. After God expelled Adam from this blessed place, he rubbed his gums with this skin so that he could not find his way back.

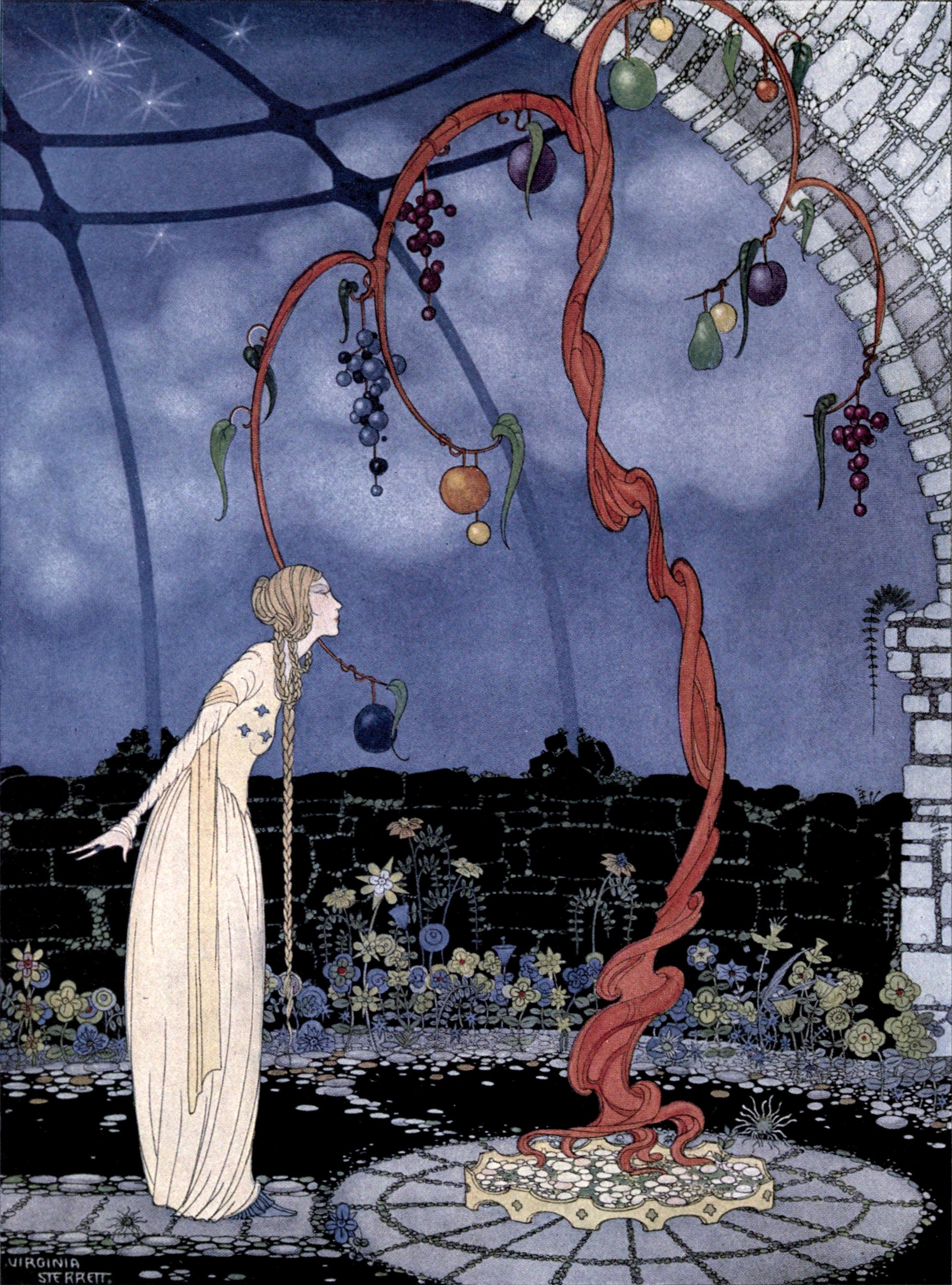

In the biblical narrative, man is sent away from Eden to cultivate the earth from which he had been made. But to cultivate the “dust of paradise,” mentioned by the erudite “inhabitant of the North,” it is first necessary to eat, beneath its thick “skin,” the subtle pulp inside the fruit of the Tree of Knowledge to find the way back to the Tree of Life and cross through the curtain of fire. This is the true object of “initiatory Work.”

Common language uses the term initiation in a wide variety of circumstances. A person can be “initiated” into the art of handling arms or the secrets of the stock market. An individual can “initiate” himself into the rudiments of a trade or art.

But this term will only be used here in its traditional sense, which involves departing on an ascending path—toward an inner light. Yet his first steps on this path will plunge the initiate into the darkness of a mystery. Its direction is indicated by the extremely orthodox etymology of the word, formed from the Latin in, “in” or “on,” and iter, “path.” Inere can be translated as “to penetrate” and as “to begin.” Initiate literally means “to set off on the path that leads within.”

Initiation is a perilous journey by boat toward a sacred center, the crossing of an ocean where the navigator quickly loses the trace of any signs of land. To protect his vessel, the course must be maintained by an expert pilot, coming from the depth of ages through what is customarily called an “initiatory tradition” in the specific sense of “transmission of a spiritual influence,” to use René Guénon’s term. Transmitted from person to person, generation to generation, this “spiritual influence” is not of human origin because it belongs to the domain of universal light out of which humans were created.

Initiation is not directed at the intellect. It is not communicable in the way a technique, knowledge, or science is taught. Closer to art because it, too, requires inspiration, initiation is the upheaval of the personality triggered by painful moral or physical ordeals, which can sometimes leave deep marks in the flesh of the initiate. Once this radical stage of upheaval has been traversed, initiation is the re-creation of the individual and his or her greater receptivity toward the interior world and the inner self.

So while information is the horizontal communication of knowledge by the exterior path of a mental representation and is directed at the “skin,” initiation is vertical participation with universal rhythm through the inner path of a ritual and involves the “pulp.”

Initiation and Fairy Tales

The valuable collection that Emmanuel Cosquin has assembled under the title Contes populaires de Lorraine opens with the story of Bear John and begins like this:

Once upon a time there was a man and wife who were woodcutters. One day when the wife was bringing soup to her husband, she was caught on a branch in the middle of the woods. While she was struggling to free herself, a bear grabbed her and carried her off to his lair. Some time later, the woman, who was pregnant, gave birth to a son who was half-bear and half-human. He was named Bear John.

Endowed with superhuman strength, Bear John, when he was seven years old, removed the boulder that sealed the entrance to the cave where he and his mother had been imprisoned, and both returned to the woodcutter’s house. Increasingly unruly and dangerous, the child was sent to apprentice to three successive smithies. After performing deplorable work, he learned the trade in which he eventually became quite skilled. He then decided to set off in search of adventure, but not before he forged for himself a walking stick to fit his enormous size. He used his last employer’s entire stock of metal: a quarter ton of iron.

The story of Bear John is often considered to be one of the oldest that people have passed down, and not without good reason. Its introduction, in Cosquin’s version, immediately draws attention to elements worth emphasizing because they evoke the time of “beginnings.” The first two characters we meet are a woodcutter’s wife and a bear. The scene takes place in the woods, a wild natural place in which any trace of civilization is absent: one of those places that in the Middle Ages were called “deserts.” The woodcutter’s wife is trapped there, snagged by a branch; in other words she is entirely dependent on nature in its primordial state. The bear has just rescued her in order to carry her off to his cave, where he makes her his mate.

The woodcutter’s wife is a woodswoman, or wild woman, from the family of “wild men,” “green men,” and “woodsmen” who were depicted in the Middle Ages as covered with hair and clad in leaves. This is a close relative to our probable tree-dwelling ancestors, whose instincts even today are probably responsible for the pleasure children feel when climbing trees, where they can dream for hours while sitting in the hollow formed by its branches—a secret world that adults have totally forgotten.

The word bear alone summons multiple resonances. In many Northern regions in both the Old and New Worlds, the bear was regarded as man’s ancestor. Depending on the time and place, the bear was “a former man, a remote ancestor, or the brother of the tribal ancestor, or the direct ancestor, the father of all humans. It could also be considered to be the maternal or paternal uncle, grandfather, grandmother, or father.” It was also a “culture hero that gave human beings fires and various tools, and taught people how to use them.” Painted “on the lower half of the leather surface of the shamanic tabor, beneath the line representing the underground world,” it is a psychopomp like the Greek Hermes Chthonios. As the two constellations of Ursa Major and Ursa Minor, the bear indicates the axis in the night sky (for an inhabitant of Earth) around which the universe revolves. In the boreal hemisphere, these constellations dominate the Arctic region, whose name derives from the Greek word for bear, arktos. Until the invention of the compass, sailors used the pole star in Ursa Minor as their guide. The two “Bears” are also the Large and Small Chariots.[3] The Saxons considered the Large Chariot as the vehicle of the mythical King Arthur, and Japanese tradition even today considers it as that of the emperor.

The bear of the story does not simply free the woman from the branches holding her captive in order to bring her to his lair, and no one is capable of sounding the depths of the den of the bear, the abyss in which the pole resides. By all evidence, the bear as a “culture hero” is an initiator and world axis. The bear is the vertical path that travels through the visible surface to soar upward and to dive downward into the invisible; it is the ladder up which the individual must climb to cross through the gates of death.

Bear John was born in the cavern of the pole, the preeminent candidate for initiation. A brutal and undisciplined child and an individual of low birth who is endowed with incredible strength, he learns the trade of forging iron, in which he becomes highly skilled, and he uses that skill to cast his cane for taking the high roads of adventure of his shining destiny. A man born of an animal, John represents the dawn of the human race, which can be viewed either from the evolutionary perspective or from that of the faith of those who see an angelic spirit that has come down to inhabit the human animal’s physical envelope. When studied closely, the two theories are not so contradictory. The beginning of Bear John’s tale suggests a fundamental parallelism between the birth of humanity in the axis of the universe and the start of its initiatory progression.

Initiation in the Western World

In all nations under all skies, the reason for the existence of initiation is the same, but the paths it takes can be different for different cultures. “If the goal is the same for all,” Guénon writes on this subject, “the starting points are infinitely varied and can be compared to the many points on a circumference from which emerge an equal number of radii that meet at a single center and are thereby the image of the very paths in question here. The pragmatic orientation of the nations of the Western world has encouraged paths based on the working and transformation of matter. These are in fact the paths offered even today by Freemasonry and alchemy, which can thus be considered the only two traditional paths whose remnants have managed to survive in our culture, despite the erroneous interpretations that both have often inspired.

Freemasonry, in its current form, based on the medieval guilds and on the symbolism of builders, assigns itself the purpose of the symbolic construction of Solomon’s Temple, in whose highly inaccessible center resides a soaring abyss.

Alchemy, which is both a practical and a symbolical discipline similar to “a physic-chemical science” but also and more importantly an “experimental mysticism,” to use René Alleau’s expression, first endeavors to create the salt of wisdom, which could just as easily be described as the “Salted temple” or the “temple of the salt of Ammon,” expressions that make two allusions to a “Lanternois”[4] justification of the renowned “wisdom of Solomon.”

While their practical progression is made by means of very different vehicles, the symbolism of Freemasonry and that of alchemy are parallel, and the final direction of the first one’s trajectory is analogous to that of the second, about which Alleau says, “It desires to free spirit through matter by freeing matter through spirit.”

The Stages

In order to be put on the path of Masonic initiation, the postulant must first be recognized as a candidate for initiation. In parallel, on the paths of practical alchemy, the first step consists of identifying the eligible subject in the mineral kingdom, that is to say the prime matter from which the Work can be started.

The human “subject” must feel as if he has been called. Where does this call come from? The one who hears it will recall a day, or a single circumstance, that aroused desire within for the other world, hidden behind his practical concerns and the objects of his everyday life.

Where can the origin of this desire be situated; how is he to recognize the chain of encounters and crossroads, the succession of paths chosen, the web of “coincidences,” dreams, and words of disconcerting resonance—everything in short that speaks to him of the castle in which Beauty lies sleeping? Fairies probably have their part in this.

Every veritable initiation begins with a descent into the subterranean reaches of consciousness, the visit “inside the earth” for which the Masonic sigil V.I.T.R.I.O.L. is an invitation. Is it by chance that the most powerful acid discovered by ancient chemistry was the one it called “oil of vitriol,” the SO4H2 of the French nobleman and chemist Antoine-Laurent de Lavoisier’s successors? As if under the effect of a powerful corrosive, the mental construction of the “profane” would be dissolved during this fall into darkness. This is the phase in which the aspiring Freemasons “strip their metals.” This takes place in a dark cave where silence and solitude hang heavily. The alchemists, meanwhile, often designated their mysterious prime matter with the name of “vitriol.” Medieval iconography and alchemical symbolism everywhere have depicted the initial dissolution, the prerequisite for opening the “door of the temple,” as the battle between a knight and a dragon.

The obvious consequence of the dissolution of a structure—whether that of a metal or a mind—is the death of all it supported, and the physical result of this produces chaos. It is from chaos that the “canonical” labor of the alchemist begins. And it is only after the death of his “profane” ego* at the threshold of Masonic initiation that the neophyte is introduced into the sacred enclosure and deprived of sight in order to undergo ordeals, the first of which follows a plunge into a world before the “beginning of time” in a space of complete disorder and imbalance. However, there is no lack of attentive hands to help support the neophyte, invisible guides who seem to have loomed up from elsewhere and without whose assistance he would never escape from the labyrinth.

The destruction of the form inside the ground has liberated a seed. Below it plunge its roots and above it rises the stem of the new plant that spring will cause to emerge into the air, shape with water, and bloom beneath the sun when it has successfully passed the test of fire to prove itself worthy of receiving the sun’s light. This is how the initiate is born on a level of existence that places him on the path of higher consciousness.

Operative alchemy has a similar process for the “stone” during the “First Work,” whose purpose is the creation of primal mercury or “common mercury.”

There are countless “fairy tales” bearing signs, clues, and counsels related to the operative phases of the Great Work and to the stages of the path of initiation. It is in search of these that the following pages will be devoted, thanks to the examination of stories taken for the most part from the collection of the Grimm Brothers and that of Emmanuel Cosquin, as well as Paul Delarue and Marie-Louise Ténèze’s Le conte populaire français (The French Folk Tale) or the regional anthologies published by Erasmus Editions in the middle of the last century.

***

1. *From the Latin in, meaning “in” and “on,” and iter, meaning “path,” “trajectory,” “journey”

2. *According to certain Australian and South American legends, fire was originally hidden inside the belly of a woman. This association of fire and womb is confirmed in ancient Greek, for whom the word eschara meant both “an altar fire” and “the female sex organs.”

3. *[In English they are now more commonly known as the Big and Little Dippers. —Trans.]

4. *[Lanternois is based on the land of learning, “Lantern Land,” in the work of François Rabelais. —Trans.]

5. *I need to stress the fundamental difference between the liberation for the individual with regard to his social “ego,” which is the case here, and the abandonment of ego for subservience to the interests of a sect, which would fall under the heading of counterinitiation.