The following is excerpted from the essay “H.R. Giger and the Zeitgeist of the Twentieth Century,” included in Modern Consciousness Research and the Understanding of Art, by Stanislav Grof, M.D., recently published by the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies (MAPS).

The stress and excessive demands of modern life, alienation, and loss of deeper meaning of life and of spiritual values engendered in many people a consuming need to escape and seek pleasure and oblivion. The use of hard drugs—heroin, cocaine, crack, and amphetamines—reached astronomic proportions and escalated into a global epidemic. The empires of the drug lords and the vicious battle for the lucrative black market with narcotics on all its levels contributed significantly to the already escalating crime rate and brought violence into the underground and streets of many modern cities.

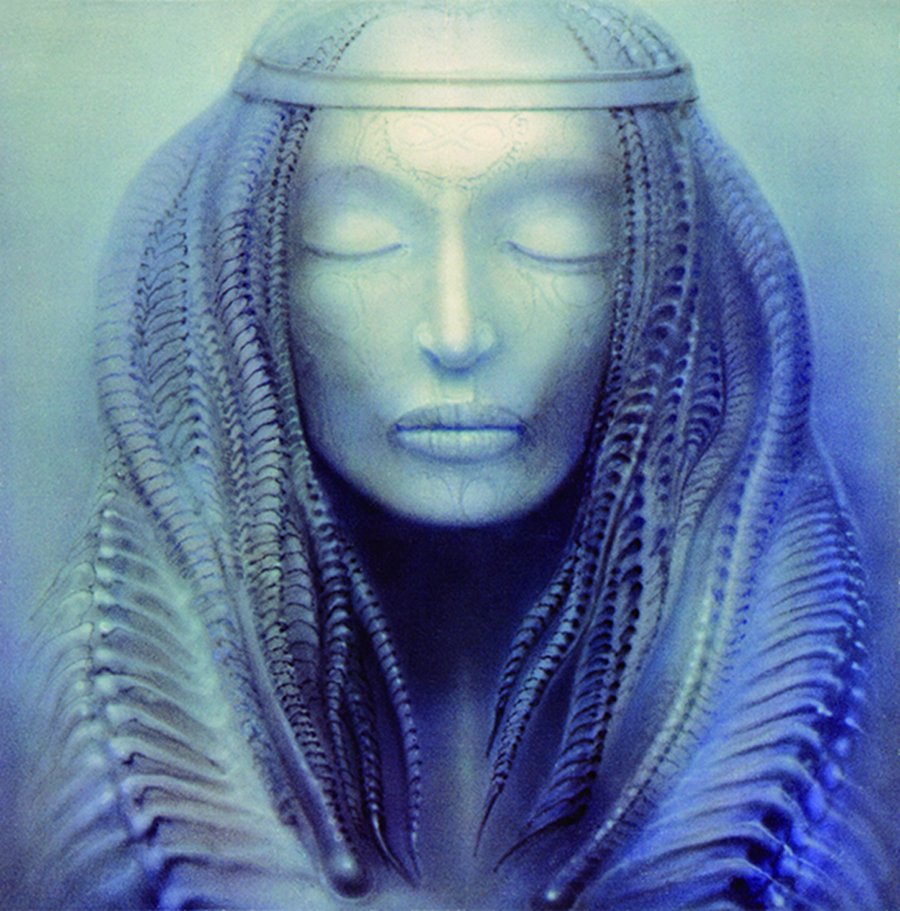

All these essential elements of the twentieth century’s Zeitgeist are present in an inextricable amalgam in Giger’s biomechanoid art. The entanglement of humans and machines has been over the years the leitmotif in his paintings, drawings, and sculptures. In his inimitable style, he masterfully merged elements of dangerous mechanical contraptions of the technological world with various parts of human anatomy—arms, legs, faces, breasts, bellies, and genitals. Equally extraordinary is the way in which Giger blended deviant sexuality with violence and with emblems of death. Skulls and bones morph into sexual organs or parts of machines and vice versa to such degree and so smoothly that the resulting images portray with equal symbolic power sexual rapture, violence, agony, and death. The satanic dimension of these scenes is depicted with such artistic skill that it gives them archetypal depth.

Giger portrayed in his unique way the horrors of modern war, the specter that plagued humanity throughout the twentieth century as part of everyday reality or as a haunting vision of possible or plausible future. We can think here about his Necronom II, the three-headed skeletal figure wearing a military helmet, which combines in a terrifying amalgam symbols of war, death, violence, and sexual aggression. Many of Giger’s paintings depict the ugly world of the future, destroyed by excesses of technology and ravaged by nuclear winter—a world of utter alienation, without humans and animals, dominated by soulless skyscrapers, plastic materials, cold steel structures, beton, and asphalt. And in his Atomic Children, Giger envisioned the grotesque population of mutants, who have survived nuclear war or the accumulated fall-out of the nuclear energy plants. Allusions to drug addiction appear throughout Giger’s work in the form of syringes inserted into the veins and bodies of his various characters.

There is one recurrent motif in Giger’s art that at first glance has very little to do with the soul of the twentieth century—the abundance of images depicting tortured and sick fetuses. And yet, this is where Giger’s visionary genius offers the most profound insights into the hidden recesses of the human psyche. Adding the prenatal and perinatal elements to the symbolism of sex, death, and pain reveals depth and clarity of psychological understanding that by far surpasses that of mainstream psychiatrists and psychologists and is missing in the work of Giger’s predecessors and peers—Surrealists and Fantastic Realists.

Mainstream psychology and psychiatry is dominated by the theories of Sigmund Freud, whose ground-breaking pioneering work laid the foundations for modern “depth-psychology.” Freud’s model of the psyche, however avant-garde and revolutionary for his time, is very superficial and narrow, as it is limited to postnatal biography and the individual unconscious. The members of his Viennese circle who tried to expand it, such as Otto Rank, with his theory of the birth trauma (Rank 1929), and C. G. Jung, with his concept of the collective unconscious and the archetypes (Jung 1956, 1960), became renegades. Rank was ousted from the psychoanalytic movement and Jung left it after a heated confrontation with Freud. In official handbooks of psychiatry, the work of these renegades is usually discussed as historical curiosity and considered irrelevant for clinical practice.

As we have seen, Freud’s theories had a profound effect on art. Freud’s discovery of sexual symbolism and his interpretation of dream imagery was one of the main sources of inspiration for the Surrealist movement. In the 1920s, Freud was even referred to as “patron saint” of Surrealism. It became fashionable for the artistic avant-garde to imitate the dream work by juxtaposing in a most surprising fashion various objects in a manner that defied elementary logic. The selection of these objects often showed a preference for those which, according to Freud, had hidden sexual meaning.

However, while the connections between the seemingly incongruent dream images have their own deep logic and meaning, which can be revealed by analysis of dreams, this was not always true for Surrealistic paintings. Here shocking juxtaposition of images often reflected empty mannerism missing the truth and logic of the unconscious dynamic. This can best be illustrated by considering the famous Surrealist dictum, which poet-philosopher André Breton borrowed from Count de Lautréamont’s (Isidore Ducasse’s) Chants de Maldoror (Songs of Maldoror). This succinct statement describing the aesthetic of jarring juxtapositions represents a manifesto of the Surrealist movement: “As beautiful as the unexpected chance meeting, on a dissecting table, of a sewing machine and an umbrella.”

Another important inspiration for Surrealism was medieval alchemy. André Breton came across a medieval image from one of the alchemical texts, representing the synopsis of the first and second opus of the “royal art”. The picture was extremely complex and featured all the most important symbols used to portray various stages of the two works of the alchemical process. Breton was fascinated by the fantastic array of seemingly incongruous images that this picture brought together and the shocking surprise it induced in the viewer. As C. G. Jung discovered in twenty years of his intense study of alchemy, the alchemical symbolism—like the symbolism of dreams—reflects deep dynamics of the unconscious and reveals important hidden truth about the human psyche. The same certainly cannot be said about most of surrealist art.

While the combination of a sewing machine, a dissecting table, and an umbrella might provide an element of surprise for the viewer, it would be very difficult to find a meaningful psychodynamic connection between these three images. Similarly, the assemblies of objects in most surrealist paintings would not make much sense to an alchemist familiar with the symbolism of the “royal art.” Giger’s art is diametrically different in this regard. The combinations of images in his paintings might seem illogical and incongruous only to those who are not familiar with the discoveries of pioneering consciousness research in the last several decades. The observations from the study of holotropic states of consciousness have revealed that Giger’s understanding of the human psyche was far ahead of mainstream professionals, who have not yet accepted the new observations and integrated them into the official body of scientific knowledge.

Giger spent many months analyzing his dreams, using the technique invented by Sigmund Freud and described in his Interpretation of Dreams. This focused self-exploration provided the inspiration for Giger’s collection of drawings entitled Feast for the Psychiatrist (Fressen für den Psychiater)(Giger 2000). However, Giger’s self-analysis reached much deeper than Freud’s. By seeking the source of his own nightmares, terrifying visions in psychedelic self-experiments, and disturbing fantasies, Giger discovered, independently from the pioneers of modern consciousness research and experiential psychotherapy, the paramount psychological importance of the trauma of biological birth.

Unlike the psychoanalytic renegade Otto Rank, author of the book The Trauma of Birth, whose primary emphasis was on the “paradise lost” aspect of birth—the unfavorable comparison of the prenatal and postnatal state and craving to return to the maternal womb, Giger’s emphasis was on the various forms of distress associated with the torturous passage of the fetus through the birth canal. It is interesting to notice in this context that Sigmund Freud, during the very short period when he considered that biological birth might be psychologically important as a possible source of all future anxieties, came closer to Giger’s understanding of birth than Rank. Freud put emphasis on the difficult emotions, physical sensations, and innervations generated by the passage through the birth canal, rather than the loss of the intrauterine paradise.

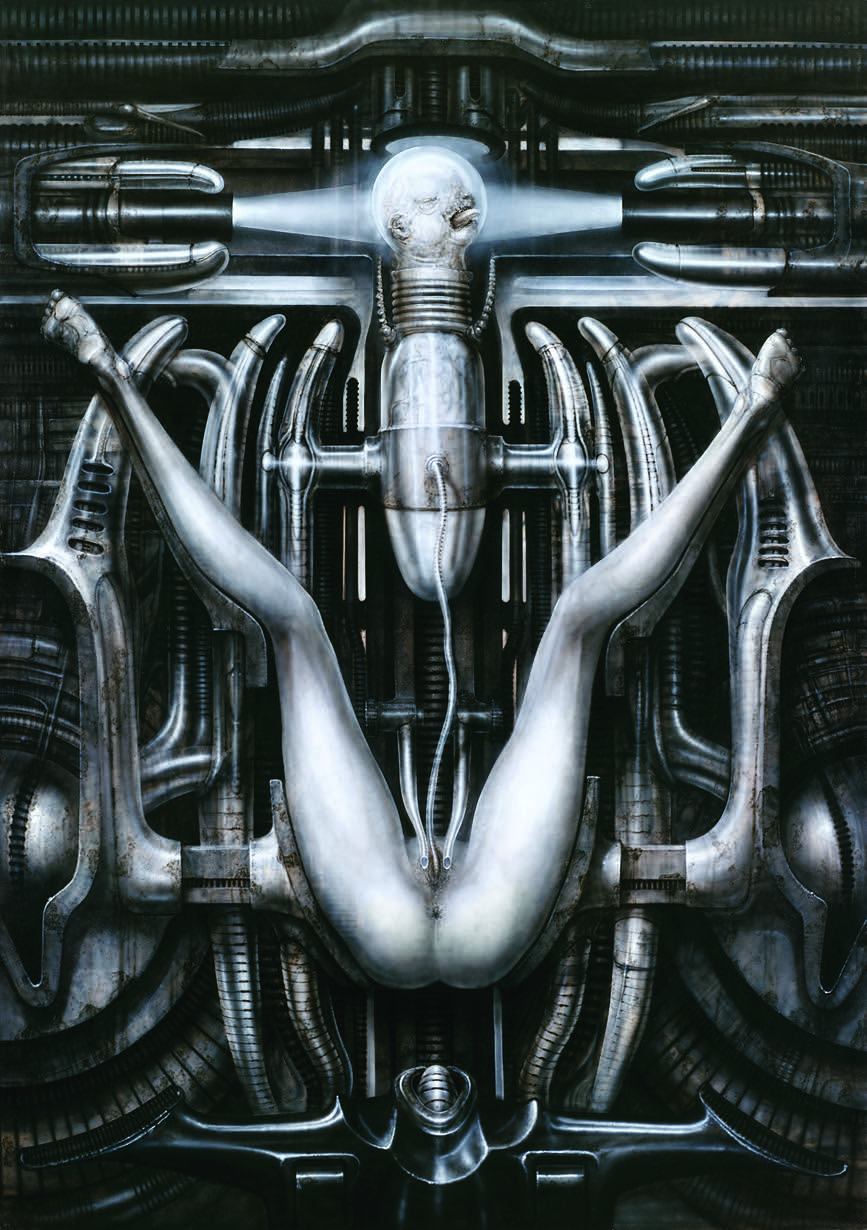

However, Giger went far beyond Freud’s relatively tame description of the passage through the birth canal; he captured the torturous ordeal the fetus has to endure in the grip of the “death-delivering machine” of the uterus. Steel rings and vises crushing the heads, mechanical contraptions with cogwheels, compressing pistons, and spikes that can hurt feature abundantly in his paintings. Equally frequent are elements associated with the emotions and physical feelings accompanying the difficult passage, such as grotesque, repulsive, terrifying, and demonic creatures, sadistic archetypal figures, vomit, and other scatological motifs. As we will see, Giger’s’s understanding of the psychological impact of birth has been confirmed by modern consciousness research.

The very term used for Giger’s art—biomechanoid—reflects the nature of human birth. Birth takes place within a biological system—female reproductive organs—and is governed by anatomical, physiological, and biochemical laws. Yet, at the same time, it has a distinctly mechanical features, which it shares with the world of machines—the power of the uterine contractions oscillating between fifty and a hundred pounds, pushing the fetus against the narrow opening of the pelvic opening and its hard surfaces, forceful torques, and the hydraulic quality of the process. It is thus not far-fetched when Giger used for his paintings the name “birth machine” and portrayed the birth mechanism as a system of cylinders and pistons.

The existence of a fascinating and important domain in the human unconscious, which contains the shattering memory of our passage through the birth canal, intuited by Giger and reflected in his art, has not yet been recognized and accepted by official academic circles. Intimate knowledge of this deep realm of the psyche is also absent in the work of Giger’s predecessors and peers—Surrealists and Fantastic Realists. Giger’s artistic skills and his talent to portray the Fantastic match those of his models—Hieronymus Bosch, Salvador Dalí, and Ernst Fuchs, but the depth of his psychological insight is unparalleled in the world of art.

Some critics described Giger’s work as being simultaneously a telescope and a microscope revealing dark secrets of the human psyche. Looking into the deep abyss of the unconscious that modern humanity prefers to deny and ignore, Giger discovered how profoundly human life is shaped by events and forces that precede our emergence into the world. He intuited the importance of the birth trauma not only for postnatal life of the individual, but also as source of dangerous emotions that are responsible for many ills of human society. He said about the tapestry of babies he painted:

“Babies are beautiful, innocent and, yet, they represent an uncanny threat and beginning of all evil. As carriers of all kinds of plagues, they are predestined to represent the psychological and organic harms of our civilization.”

One could hardly imagine a more powerful representation of the terrifying ordeal of human birth than Giger’s Birth Machine, Death Delivery Machine, or Stillbirth Machines I and II. Equally powerful birth motifs can be found in Biomechanoid I, featuring three fetuses as heavily armed grotesque Indian warriors with steel bands constricting their foreheads, in Giger’s self-portrait Biomechanoid II on the poster for the Sydow-Zirkwitz Gallery showing him as a helpless warrior encased in a heavy metallic cage, and in Landscape XIV that portrays an entire tapestry of tortured babies. The symbolism of Landscape X is more subtle and less obvious; here Giger combined the uterine interior, symbolizing sex and birth, with black crosses in the shape of Swiss army’s targets for shooting practice that signify death, as well as violence. Echoes of birth symbolism can also be easily detected in his Suitcase Baby, Homage to Beckett, and throughout his work.

Two motifs that appear in Giger’s art do not involve explicitly fetal images, but represent important perinatal symbols—the spider and the volcano. As we saw earlier, spider is an image that often appears in the context of psychedelic or holotropic sessions dominated by the second perinatal matrix (BPM II), usually in the form of giant terrifying tarantulas. As C. G. Jung correctly described in his book Symbols of Transformation (Jung 1956), spiders often symbolize the Devouring Feminine. This reflects the fact that they rob insects of spatial freedom, something that the fetus experiences in a good womb. The explosive liberation during the final stages of birth often takes the form of experiential identification with a volcano. Both spiders and volcanoes belong to Hansruedi Giger’s favorite themes.

Once we have recognized the prenatal and perinatal roots of Giger’s art, it is easy to understand why he incorporated into his drawings, paintings, and sculptures the motif of syringes, toxic substances, and drug addiction. Most of the disturbances of prenatal life are due to toxemia of the mother and for many of us the anesthesia administered at our birth represented our first escape from pain and anxiety into a drug state. It does not seem to be an accident that the generation afflicted by the current drug epidemic was born after obstetricians started using anesthesia routinely and indiscriminately in delivering mothers.

Hansruedi Giger was in touch with the perinatal domain of his unconscious since his childhood. He had always been fascinated by underground tunnels, dark corridors, cellars, and ghost rides. Many of his nightmares and experiences during his psychedelic self-experiments spawned by his memory of the birth trauma gave him a deep understanding of the symbolism of the perinatal process. He knew intimately the agony of the embryo in a hostile or toxic womb, as well as the suffering of the fetus during the arduous passage through the birth canal. And he was fully aware of the fact that the source of this knowledge was his own memory of birth. The following is his description of one of his nightmarish experiences, involving the sense of terrifying engulfment characteristic for the onset of the birth process (BPM II):

“Again horror took control of me. Harmless passersby who my mind turned into insane murderers had to be avoided by making wide detours around them. Everything seemed evil to me. The houses, the trees, the cars. Only water could placate my spirit. I felt as if I was about to be swallowed by a hole. The sidewalk became so steep that I was always about to fall off it and into the adjoining gorge. With tears streaming from my eyes, I clutched onto Li (his girlfriend at the time) without whom I would have been lost.”

Experiences of this kind were not limited to Giger’s dream life: they occasionally occurred in the middle of his everyday life. Horst Albert Glaser made the following comment about this aspect of Giger’s life: “The artist has always been interested in what might be called the cracks in a seemingly smooth daily life. Places where the dreamer steps into a bottomless abyss and the sleeper contorts his body—this is what captures the artist’s frightened inner child. What seems to be the road to freedom is a plunge into black nothingness.”

The motif of the engulfing vortex that transports the subject into a terrifying alternate reality appears in several of Giger’s paintings. I mentioned earlier in this book that another experiential variety of the beginning of birth is the theme of descending into the depths of the underworld, the realm of death, or hell, known from the initiatory visions of the shamans and from the mythology of the hero’s journey, as described by Joseph Campbell in his book The Hero with a Thousand Faces (Campbell 1968).

This immediately brings to mind Giger’s childhood fantasies of monstrous labyrinths, spiral staircases, and subterranean enclosures that served as inspiration for his Shafts and Under the Earth. The claustrophobic nightmarish atmosphere of a fully developed BPM II dominates many of Giger’s paintings. He portrayed with extraordinary artistic power the torment, anguish, and hopeless predicament of the fetus caught in the clutches of the uterine contractions and the ordeal of the delivering mother. Clinically, this is the domain of the unconscious that underlies deep depression. But Giger’s masterful depictions of the no exit situation reach beyond the ordeal of the fetus to other situations involving similar desperate ordeals.

Giger’s art features torture chambers, in which various eerie creatures are tied, stabbed, mutilated, crushed, and crucified. His incisive probing vision traces this suffering to its sources in the archetypal depth of the psyche, where it assumes hellish dimensions. Giger’s gallery of bizarre mutants represents a category of its own. These strange creatures are not like Frankenstein’s monster, who was composed entirely of heterogeneous human parts, nor are they android robots, lifeless automatons only remotely resembling people and imitating human activities. Giger’s biomechanoids are strange hybrids between machines and humans, like the Cyborgs from the Star Trek space odyssey, and they are surrounded by a world that itself is biological and mechanical at the same time. As we have seen, this is the same combination that characterizes childbirth.