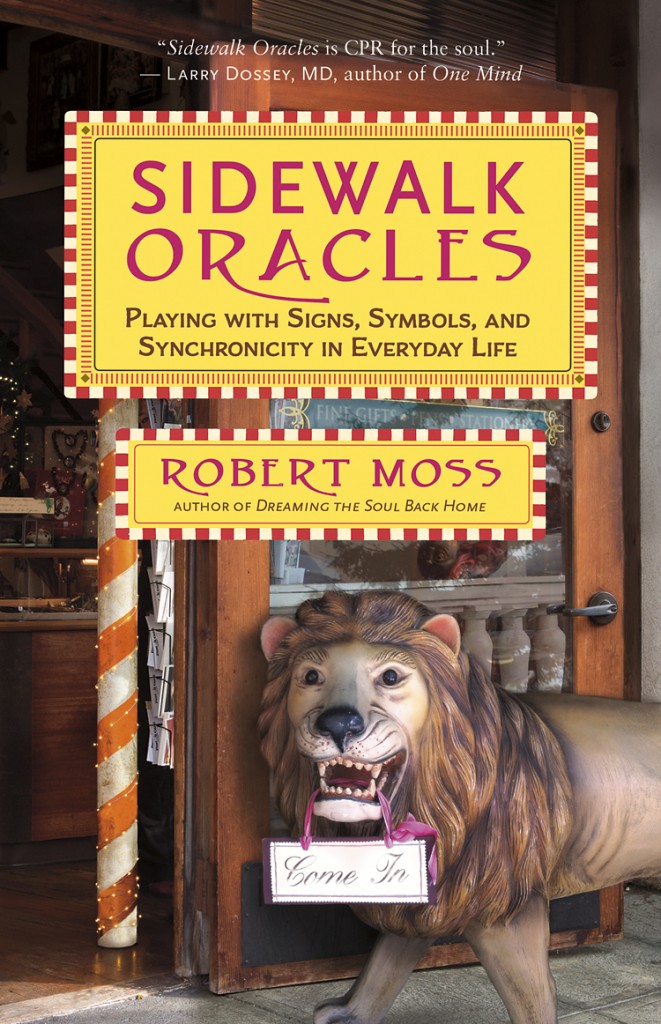

The following is excerpted from Sidewalk Oracles: Playing with Signs, Symbols and Synchronicity in Everyday Life by Robert Moss, published by New World Library.

Jung dreamed of a tower and he built it, on old church land at the edge of the village of Bollingen, on the shore of the Obersee basin of Lake Zurich. He started work soon after his mother’s death in 1923. What began as a simple neo-medieval tower with a pointed roof grew, in successive waves of inspiration and construction, into a small castle. Jung embarked on the final phase of construction after his wife Emma’s death in 1955, adding a high upper room he called “the chapel” to the middle building between what were now two towers. He painted the walls with scenes of other times and filled the room with things that took him “out of time, out of the present.”

He always refused to install electricity and indoor plumbing. He lived here like a farmer of an earlier time, pumping his own water, chopping wood for his fire, lighting his candles and oil lamps, cooking his hearty stews. He spent several months of the year at Bollingen. He came for solitude and simplicity, leaving behind his patients, his lecture room audiences, and his persona as professor and professional analyst. He went about in old, comfortable clothes and was often to be seen in overalls and even, on occasion, washing a pair of jeans. He did the best of his creative writing here in the last period of his life.

Very often, if you were nearby, you could hear the tap of Jung’s chisel or the clang of his hammer. He worked here with stone as well as paper, covering many surfaces with images and inscriptions. He called the whole place his “confession in stone.” Some of the things he carved are there for any visitor to see; some are hidden. One of the hidden inscriptions reads, in Latin, Philemonis sacrum Faust poenetentia [sic], which means “sanctuary of Philemon, penitence of Faust.” Philemon was the name by which Jung knew the spiritual guide whose importance is fully revealed in the Red Book, the guide who, as he wrote, convinced him of the objective reality of the psyche and its productions. Philemon is also the name, in the myth, of a kindly old man who gives hospitality to gods who are traveling in disguise — and is killed, together with his gentle wife, through the greed and megalomania of Faust, the model of heedless Western man, in part 2 of Goethe’s Faust.

When he was writing his essay on synchronicity, Jung carved the face of a laughing Trickster on the west wall of the original tower.

Jung’s confession in stone contains many images that spark fire in the imagination but do not immediately yield explanation, except where Jung has added words, always in Greek or Latin, which he read fluently. Here is a woman reaching for the udder of a mare. Here is a bear behind her, apparently rolling a ball. Here is Salome. Here is a family crest.

The best story of Jung’s stonework involves the block that was not supposed to be delivered. Jung wanted to build a wall for his garden. He engaged a mason who gave exact measurements for the stones required to the owner of a quarry while Jung was standing by. The stones were delivered by boat. When unloaded, it was clear at once that there had been a major mistake. The cornerstone was not triangular, as ordered. It was a perfect cube of much larger dimensions, about twenty inches thick. Enraged, the mason ordered the workmen to reload this block on the boat. Jung intervened, saying, “That is my stone! I must have it.” He knew at once that the stone his mason had rejected would suit him perfectly for a purpose he did not yet understand.

Fairly soon, he decided to chisel a quotation from one of his beloved alchemists on one side of the cube. But something deeper was stirring, through affinity between Jung and the stone itself. On a second face of the stone, he saw something like a tiny eye, looking at him. He chiseled a definite eye. Around it he carved the shape of a little hooded figure, a homunculus. He had a name for this figure, Telesphoros. The name means “one who guides to completion.” In Greek mythology, he is a son of Asklepios, the patron of dream healing. This figure was a recurring archetype in Jung’s inner life, one he sought to give physical form with pen and chisel and, as a boy, with a pocket knife. When he was ten years old, Jung carved a little manikin of this kind from a school ruler and kept it hidden in a box. He regarded this as his first great secret in life, and “the climax and conclusion” of his childhood.

Now, around Telesphoros, he chiseled words in Greek that came to him. In Memories, Dreams, Reflections they are translated as follows: “Time is a child — playing like a child — playing a board game — the kingdom of the child. This is Telesphoros, who roams through the dark regions of this cosmos and glows like a star out of the depths. He points the way to the gates of the sun and to the land of dreams.” The broken first sentence is a loose translation of one of the most mysterious and compelling fragments of the ancient Greek philosopher Heraclitus. Key words are open to rival translations. The word Jung renders as “time” is aion, and that is perhaps not a strong enough rendering. A recent translation of the line from Heraclitus offers this: “Lifetime is a child at play, moving pieces on a board. Kingship belongs to the child.”

I wonder whether Jung played with the idea, as he chiseled, that what Heraclitus was talking about was a secret law of manifestation, perhaps none other than what Jung dubbed synchronicity. Beyond logic, beyond causation as it is commonly understood, the play of forces outside time determines what happens within the human experience of time. Play is what we must be most serious about. Play in the spirit of the child, who plays without concern for consequences, because the play is the thing.

So: “Synchronicity is a child at play, moving pieces on a board.” On our side of reality, we see the pieces move, but not the hand that moves them.

Jung once said that he could bear the thought of being reincarnated back into this world if he could have Bollingen again. Toward the end of his life, however, he knew for sure that there was a second Bollingen, ready for him on the other side. He dreamed that he saw the other Bollingen bathed in a glow of light. A voice told him that it was now completed and ready for him to move in. Far below its towers, he saw a mother wolverine in the water, teaching her kit to dive and swim.

Jung told this dream to two women, both analysts, who were close to him and had chosen to carry on his legacy. He was nearing eighty-five, his once robust health and energy were variable, and he had lost his “two wives,” Emma and Toni Wolff. Jung and his confidants understood that the dream of the other Bollingen was making him familiar with death, showing him that he had a beautiful place to go on the other side and preparing him to enter a new phase of learning that would include operating in a new element, like the wolverine’s child in the water. After the dream, Jung no longer felt the urgent need to return to Bollingen that had often gripped him. He stayed away for many weeks at a time before leaving for the other Bollingen nine months after the dream.

Synchronicity crackled around Jung’s death, as he had suggested that it often does around the great turns in a life cycle. The last time he was out for a leisurely drive, he was held up by three wedding convoys, sowing thoughts of “three weddings and a funeral” decades before the film. Half an hour before she received the news of his death, his acolyte Barbara Hannah found that her car battery was inexplicably dead. An hour after Jung’s death, lightning struck a tall poplar at the lakeside edge of his garden, stripping the bark and spreading it all over his lawn.

A few months before Jung’s death, Gerhard Adler watched him as he sat at his desk in the “chapel” at Bollingen, looking out over the lake “but clearly looking out very much further and deeper. He sat, completely unaware of my presence, intensely still and absolutely concentrated, utterly alone with himself and engrossed in his inner images — the picture of a sage completely absorbed in a world of his own.”

***