The following originally appeared in the MAPS Bulletin.

Join Kevin Franciotti for the upcoming live, interactive video course “Psychedelic Science and Spirituality: How to Apply What We’re Learning to Your Life,” hosted by Brad Burge of MAPS, and discover how to apply insights from psychedelic science to your life with leading experts in the fields of psychedelic research, medicine, and spirituality. This 5 session course starts November 4. Learn more.

The faint light in the distance signals to me that the dawn is near, and yet I don’t feel as if I’ve been up all night. My body is both exhausted and restless, but my mind is clear—almost agonizingly clear. I am aware that the journey has only just begun, and while I have a slight ambivalence regarding the day that awaits me, I don’t realize just how long this day will be.

I wonder to myself, “What time is it right now?” I start to go through my mental record of the past couple of days. A mere 48 hours ago, I am sitting on the bed in my old room at my parent’s house trying to time my last shot. I intend to bring my last bag of heroin with me to the airport, and shoot up in the bathroom just before I go through security. I stare at the clock, knowing that my plane is scheduled to depart in just over three hours, but it has only been a couple of hours since my last fix. I decide that I can’t wait until getting to the airport, so I load up the needle one last time.

Less than 12 hours later, I am waiting at the passenger pickup area at the San Diego airport for my ride to the clinic. I don’t mind the wait. I walk back and forth and pull discarded, half-smoked cigarettes out of the sidewalk bins. I pace back and forth, managing to grab enough used cigarettes that I chain-smoke for the two hours it takes for my ride to arrive.

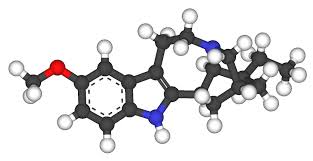

The driver, who happens to run the clinic, informs me that we need to make a nearby stop for him to pick up some forms. He tells me that he is helping to recruit subjects for a study sponsored by the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies (MAPS), an observational investigation into the long-term outcomes of ibogaine treatment for opiate addiction. We meet up with Tom Kingsley Brown, Ph.D., the Principal Investigator for the study, and he asks me if I’m interested in being a participant. I say yes, and after leaving Brown we stop at a grocery store before heading to the border.

Following the two-hour drive down the Baja California coastline I arrive at the clinic in La Misión with a sense of relief as I tour the facility and am comforted by the safe and beautiful neighboring village. I meet the staff who will be monitoring me throughout my stay—a nurse who speaks fluent English, and his assistant, who speaks only Spanish. I am shown to my room, where I lay down on the bed and immediately pass out. I don’t wake up until the next morning. I eat a light breakfast and have a discussion about my upcoming ibogaine treatment later that night, and agree that I will not have anything more to eat until the following morning. In order to enroll in the MAPS study, I read and sign the consent forms and have a Skype interview with Brown to complete my baseline measures. I inform him that while my withdrawal symptoms are relatively mild at the moment, I am anxious to proceed with the treatment.

In the afternoon the nurse leads me to a room and runs an EKG on me to make sure my heart is healthy enough to handle the medicine. Then I wait in my room until the evening to begin the treatment. About an hour before I take the medicine, the nurse runs an IV bag of nutrients to hold me over through the night. Then I receive a test dose to see that my body doesn’t react adversely to the medicine. A few minutes later, after having no reaction to the test dose, I am given a brief synopsis of what to expect from the onset of the medicine: a buzzing noise in my ear will signal that the effects are about to take hold. I start the regimen building up to what is known as a “flood dose” (around 12.5mg per kg body weight) of ibogaine HCl, swallowing three capsules spaced 10 minutes apart. Though I feel anxious with anticipation, I am relaxed and comforted by the last piece of advice—to simply open my eyes if I am overwhelmed with frightening visions.

Less than half an hour after I ingest the last capsule, I notice a bizarre sound that almost seems like it’s coming from landscaping equipment somewhere outside the window. As I wonder who could possibly be working this late at night, I remember what I was told to expect before the medicine took effect. Upon this realization, I realize that this is going to be quite an experience. Moments later, while I’m lying on my side with my eyes closed, I feel an intense rush of energy that pulsates throughout my body. Immediately I understand why it’s called a “flood dose.” My body feels washed in a cleansing energetic blanket that completely removes the physical discomfort I’m feeling after 36 hours without heroin. In my mind there’s a vision like I’m being launched through a worm-hole which spits me out into what looks like outer space. I’m having a very rapid succession of incredibly insightful thoughts and ideas, and I’m broadly contemplating various abstract concepts such as relativity theory, evolution, and photosynthesis.

I’m capable of an easy maneuverability where I’m in complete control of my thoughts, and yet I’m experiencing vivid, fluidly changing visions corresponding to every thought. I experience a rapid course of the entire history of life on Earth tracing back to before the Big Bang. There are scenes of large-scale battles among clashing tribes of human beings, with one side eventually absorbing the other and awaiting the next civilization to overthrow. Later on, more personal elements take over, such as long-forgotten memories from childhood, things I would think about at young ages and experiences I am essentially reliving. I feel a close connection to memories of my familial ancestors and of various organisms in humanity’s evolutionary past. A vision of bees dancing between patches of wildflowers changes to a scene of young infants sitting in a circle learning to share toys with each other. This part of the trip, what I later would call the “fireworks show,” lasts all through the night.

The physical sensation ends abruptly as I notice the dim light coming in through the window, and despite being able to ignore my withdrawal symptoms all night they now return with an intensity that reminds me that they were present all along. My mind is still fairly lucid but obviously altered, and I’m very unsteady when I try to stand up and walk to the bathroom. Even though the effects are not as pronounced, I remain under the influence of the medicine, so the nurse helps me to my feet and walks me to the bathroom. I lie back down on the bed, but my whole body is shaking. I’m flexing my hands and legs while tossing and turning in an effort to make the extreme discomfort even slightly more tolerable. Despite strong feelings of guilt and shame, I even feel the desire to use heroin to make the discomfort go away. The nurse who was monitoring me throughout the evening during the peak effects of the medicine leaves the room, telling me: “This is what is going to keep you clean. You will be staying in this room today.” I can only imagine what he means as I look over to the nightstand and see only a tissue box and a water bottle. I’m suddenly filled with panic at the idea that I’ll be alone all day. Maybe a day of agony is the price of admission for the fireworks show that entertained me throughout the night before.

I have no idea what time it is, but it feels like it’s been a while since sunrise. “It must be afternoon by now,” I think to myself. Though I was told to leave my phone off I have a strong desire to tell my family that I’m OK, and I’m desperate to know what time it is, how much more of this day I’ll have to endure. I’m completely alone in the room, and as I take my cell phone out of my bag and turn it on I am shocked when I read the time on the screen: 9:00 AM. Knowing how much more time lay ahead I feel defeated, confused, alone, and afraid. I send a message to my Mom: “I’m at the clinic, I’m safe and all right. Will call later.” I have no idea if she’ll receive the message, but I’m comforted knowing that at least my thoughts are with her. If I could only tell my family how much they mean to me and how sorry I am for all of the things I put them through, maybe life can go back to normal. I stand up, my muscles weak and aching from withdrawal, but I can’t lie on the bed any longer. I pace around the room; keeping my body in motion seems to distract me from the physical and emotional pain. After an hour I realize how hungry I am, and the nurse brings me breakfast: yogurt and granola with banana slices. I eat it slowly and savor every morsel. It has been over 24 hours since I last ate something, and this simple meal tastes like the most incredible dish I’ve ever eaten.

After hours of pacing, I lie back down on the bed, still feeling wide-awake. I stare at the wall across the room and I am struck by the pattern bordering the closet and bathroom doors. I didn’t notice it earlier, but it’s an image of flower patches with bees flying between them, just like the vision I had. I smile at this synchronicity, and start to feel a relief as I notice the sun beginning to set. The nurse calls me to dinner, and I’m treated to another delicious meal: salmon and wild brown rice. After dinner I return to my room and listen to music. The nurse comes in around 11pm and gives me some sleep medicine. The pills don’t do much, but I manage to rest for a few hours on and off throughout the night.

The following morning I feel like a new person. I eagerly complete the post-treatment interview with Brown, telling him that ibogaine successfully attenuated my withdrawal and I have a new perspective on my life because of the medicine. I stay at the clinic for an additional five days to relax and reflect on my experience and the direction I want my life to take from here on in. For the first time in my life, I accept that my unhealthy relationship with drugs reflect a deeper need for healing than just detoxing from opiate dependency. While I recognize the help that long-term aftercare will have on my ongoing recovery, I am apprehensive about the structured treatment that I agreed with my family to follow through on after I leave the clinic. Then I recall my experience with ibogaine, how I felt a guiding embrace that seemed to come from a place of unconditional love and genuine care for my well-being. I feel profoundly humbled, as I realize that my parents are also coming from that same place, so I decide that it’s time to accept the help that the people who love me are offering.

I’m driven back to the airport in San Diego and board a flight to south Florida, where I meet with my parents and agree to move into a halfway house. The requirements for staying at the house include complete abstinence from drugs, get a job, attend a 12-step meeting every day, obtain a sponsor, and submit to random urine screenings. In addition to the accountability required by the halfway house, my lawyer got the judge to allow me to complete the treatment court program in Florida. This involves attending three group sessions a week at an outpatient treatment program for a year. As if the mandated accountability measures I have to complete to remain out of jail and off the street are not enough, I have a phone interview once a month with Brown to update him on my progress and complete structured interviews for the MAPS study. He also sends me two psychological surveys each month, which I complete and mail back to him. I regularly submit urine tests for the halfway house and the outpatient program, and separate hair tests seven months and 12 months after the ibogaine treatment for Brown’s study.

There are some modest moments of celebration that accompany my first year of recovery, including completing a seven-month stay at the halfway house and graduating from treatment court with all of my charges dropped. But as an avid believer and supporter of psychedelic medicine and MAPS, I am perhaps most proud to bring strong evidence to Brown’s study, that ibogaine and aftercare helped me remain completely abstinent from drugs and alcohol for the entire year following treatment. My recovery continues, and I remain abstinent today—over four years since taking ibogaine. Since those early days of recovery, I returned and completed my undergraduate program at the university I withdrew from when my addiction became more important than my classes. I am currently applying to graduate programs in psychology with the hope of working with the same medicines that helped save my life. I have meaningful relationships with my friends and family, and perhaps above all else I am profoundly happy to have the opportunity to embrace the fullness of life.