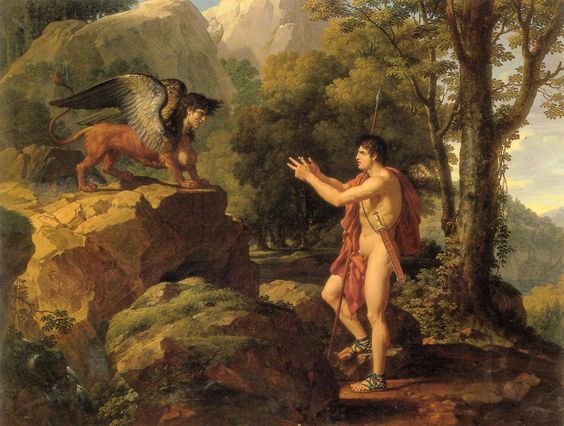

“The city of Thebes was afflicted with a monster which infested the highroad. It was called the Sphinx. It had the body of a lion and the upper part of a woman. It lay crouched on the top of a rock, and arrested all travellers who came that way, proposing to them a riddle, with the condition that those who could solve it should pass safe, but those who failed should be killed. Not one had yet succeeded in solving it, and all had been slain. Oedipus was not daunted by these alarming accounts, but boldly advanced to the trial. The Sphinx asked him, ‘What animal is that which in the morning goes on four feet, at noon on two, and in the evening upon three?’ Oedipus replied, ‘Man, who in childhood creeps on hands and knees, in manhood walks erect, and in old age with the aid of a staff.’ The Sphinx was so mortified at the solving of her riddle that she cast herself down from the rock and perished.”

— Thomas Bulfinch, The Age of Fable (S. W. Tilton & Company, 1855)

Not far from where I live stands a tall hill, which I sometimes surmount as a means of exercise while on neighborhood walks. My regimen is far from perfect, and during long stretches of concentrated desk-work I tend to let these walks go by the wayside.

Such was the case last autumn as I completed laying out The Troll Cookbook, my collaboration with Karima Cammell. I had jettisoned regular exercise during the final weeks of preparing the book for press, and let myself be consumed by the process. Or perhaps it’s more accurate to say consumed by something, and this something had a taste for my knees, a fact that became painfully apparent each time I rose from my desk, my knee joints aching and emitting faint crackling sounds. They complained further if I stood upright for longer than a few minutes, or when I walked down stairs.

This didn’t strike me as the healthiest turn of events, and I realized that I’d been favoring my mental, inner life at the expense of my physical form. “Use it or lose it,” the saying goes, and I was losing it. So the next available morning — it happened to be a Monday — I set off around dawn to climb the hill.

During the walk I pondered the legend of the sphinx and the enigma of the three-legged creature. Indeed, what strange animal had I become, puffing a bit and eagerly gripping the railing on a staircase set into the hillside as I made my semi-triumphant descent home? I certainly was not a creature who walked on two legs alone. The ripe old age of 41 seemed too early to succumb to frailties, though, so I vowed to climb the hill every day for a month and see how I felt, weak knees be damned.

The exercise paid off fairly immediately. By Friday the aching and crackling had subsided, and within a few weeks I was making the climb in rude health. The movement, and the fresh air, and the vistas glimpsed from atop the hill rejuvenated my psyche as well, and reminded me of the necessity of finding balance between inner and outer activity, that each feeds the other and leads to a healthier life.

To Stave Off Mortality

In his foundational book of occult philosophy, Transcendental Magic, Eliphas Lévi considers the answer to the sphinx’s riddle to be both literal and metaphoric, and applicable to mankind’s spiritual development as well, saying, “Infant humanity walks on four legs, evolving humanity on two legs, and to the power of his own mind the redeemed and illuminated magus adds the staff of wisdom. The sphinx is therefore the mystery of Nature, the embodiment of the secret doctrine, and all who cannot solve her riddle perish. To pass the sphinx is to attain personal immortality.”

It’s a bold claim, to be sure, but one which resonated with my musings on the sphinx’s connection to inner life. I don’t hold out hope for attaining physical immortality in this life, nor do I think I’d enjoy it. There are parts of ourselves we can cultivate that carry on past our earthly existences, though. Our children, our finances, the results of our careers, and the memories we leave our loved ones are all examples of this. For the ambitiously creative among us, though, deathlessness is largely attained through our completed works of art, a process which takes artwork and artist alike through a four-, two-, and three-legged progression, one watched over by the harshest, most bloodthirsty critic ever known. Whether the sphinx is seen as a metaphor for society, the artist’s self-doubt, or the creative process itself, if there is to be art—immortality attained—then the monster must be defeated and toppled from its perch.

Following the artist’s initial creative impulse, a period of time is spent “crawling,” so to speak. Whether it’s true literally (imagine Jackson Pollock lurching around atop his canvas) or purely figuratively (the philosopher turning an idea over in her mind), this early stage of the creative process is all about discovery. The infant crawls on all fours; the artist immerses herself in the material. Research and play can be as one, and the phrases “messing around” and “getting your hands dirty” bear this out as the artist absorbs—and is absorbed by—the work at hand. In mythological terms, here we may say that Oedipus approaches the sphinx, who compels him to answer the riddle.

If fruitful, this opening four-legged phase culminates in a breakthrough flash of understanding, a revelation rivaling the original inspiration, a conquering moment of “standing up.” The artist no longer crawls through the creative landscape but now, on two legs, exists in relation to it. The substance of the art—be it pigment for the painter, clay for the sculptor, or language for the writer—is tamed, brought under control, or at least into negotiation. The artist is no longer subject to the whim of the material but may provide direction of her own. It is only now, the artist standing upright, that it may be shaped according to the extent of her will and ability: the dexterity of the painter or sculptor, for example, or the vocabulary of the writer. There is a meeting between artist and artwork, and for a time they are in dialogue with one another. Oedipus considers the riddle. The sphinx leans forward with a hungry look in its eyes.

The Sphinx Overthrown

At this point the riddle must be solved, the nature of the third leg discovered. If the creative process is to reach culmination, then something original—something perhaps even clever or profound—needs to be brought to the work. The form and deployment of this final ingredient is up to the artist, and is influenced by a number of factors, among them skill, material resources, and previously accumulated wisdom. It need not be a dramatic change, and indeed some of the world’s most potent artwork finds its strength in subtlety, but when it is done both artwork and artist are transformed. Oedipus answers, and the cruel sphinx is sent hurtling from its woeful throne.

The immortality of the three-legged creature isn’t confined to myth and philosophy, but is a physical reality in our world. Stood upright, a chair with only one leg will tip over immediately. A two-legged chair (such as the ones given to groggy milkmaids) falls just as quickly if the person atop it loses concentration, and a chair with four legs wobbles if imperfectly made, or if the floor beneath it is uneven. In contrast, the three-legged chair can stand without teetering indefinitely, and is nimble enough to do so even on rocky ground.

A three-legged fate awaits all of us fortunate to live long enough. The construction of our staff of support, however, is entirely in our own hands. An artistic practice is only one of the ways it may manifest. Physical health, a set of glad memories, a robust garden or thriving business, regular gatherings of family and friends, accumulated wealth or good will…each upholds us through life’s trials, and perhaps even allows parts of ourselves to carry on past this life. We crawl, we stride, and by journey’s end we stand supported. In many ways, though, our travel never ends. There is always more to be discovered about the enigma of the sphinx.

By its nature, wisdom never comes without cost. The sphinx claimed many lives in its day. It’s no wonder we sometimes stumble as we travel the rugged road to Thebes, but along the way each of us finds our own means of achieving balance, and as we do, we catch sight of our own immortality.

Image: “Oedipus and the Sphinx,” by François-Xavier Fabre (1806-1808)