Danny Goldberg’s new book In Search of the Lost Chord, an antidote to 2017, introduces us to inspiring political and artistic good examples, and bad ones whose mistakes we can learn from, like a guide to people, events and culture worthy of further research.

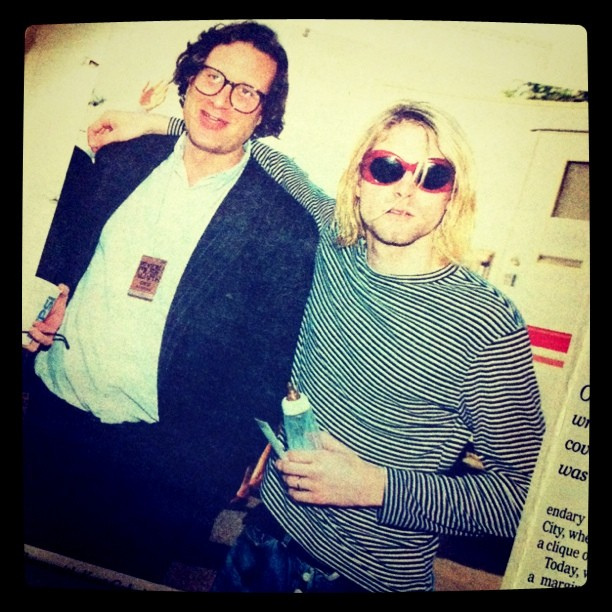

Led Zeppelin, Nirvana, Warren Zevon, Stevie Nicks, Steve Earle, the list of great artists Danny has helped develop as a manager and record company president are only part of his story. From going to high school with Gil Scott Heron in 1967 to his friendships with Patti Smith, Ram Dass, Tim Leary and Allen Ginsberg, Danny is a witness to history who writes eloquently, with brevity and humor.

2017 late Autumn is in the air. The presidency has become a reality TV show. The foundations of democracy are trembling as stories about the Yellowstone super volcano invade our feeds.

Jimi Hendrix, Janis Joplin, The Doors, Pink Floyd, Leonard Cohen, The Velvet Underground, David Bowie, Dolly Parton, Al Green, Sly and the Family Stone and The Grateful Dead, all released their first records in 1967. The Beatles released Sergeant Pepper. Kurt Cobain was born that year. That’s just a taste of the music. Every other art form had its own renaissance and so did the battle for civil rights.

But revealing the amazing events of 1967 is only part of the purpose of this book. The idea of hippie is equally important. In a recent speech Chris Hedges compared Trump to the ill fated Roman Emperor Commodus. The only note of hope Hedges had to share was that what happened in the 60’s still lives and could happen again. Not so much a cultural revolution but a collective awakening of brotherly love.

Denying the reduction of hippie to fashion and music, and the stereotype of the feckless hippie stoner, Danny includes in the conclusion of the book a brief who’s who of hippies who went on to do wonderful things themselves or with charities they helped create and guide: Michael Lerner, Bill Zimmerman, Stewart Brand, Wavy Gravy, Larry Brilliant.

Many of the themes first popularized by hippies are still important today: ecology, meditation, yoga, world music, interest in Indigenous and Asian spirituality, organic food, vegetarianism, liberated sexuality, the use of drugs especially cannabis, to moderate mental and emotional challenges and to explore altered states, resistance against a government dominated by older white males. But hippie is still a dismissive label, which brings me to my first question for Danny.

Tamra Lucid: Just before beginning this interview I posted a pic of myself barefoot wearing American flag jeans. I was called a dirty hippie. How did hippie become a dirty word? And why has it stayed that way?

Danny Goldberg: The word hippie was drained of meaning very quickly because of mass media attention, so the original spirit which I was inspired by scattered and the external symbols were used in dumbed down entertainment and appropriated by a wide array of bullshit artists. Many conservatives, most notably Ronald Reagan, quickly found the cartoonized version of hippie culture an effective whipping boy to scare and motivate enough of middle America to win elections. Many political radicals failed to understand the spiritual power of the counter-culture and were frustrated when people like the members of the Grateful Dead and Tim Leary didn’t want to take marching orders form authoritarian Marxists and the like. If I had been born in 1960 instead of 1950 and grew up with the image of hippie cliches expressed in the media I probably would have the same contempt for the word “hippie” that many in the punk movement did. One of the reasons I wrote the book was to re-discover the idealistic and spiritual essence that inspired me as a teenager and to differentiate it from the cartoon version.

You’ve worked with so many iconic artists including Led Zeppelin, Stevie Nicks, and Nirvana, and many were no doubt labeled hippies. How did they feel about that? Any stories to tell?

In the case of Nirvana, notwithstanding the name of the group, Kurt never talked to me about hippie culture. He was born in 1967 and was inspired by punk culture as a kid. Stevie Nicks somehow internalized a lot of hippie imagery and spirit and re-invented it on her own terms but I always had the sense she was very inner-directed and not reacting to sixties culture. Robert Plant and Jimmy Page of Zeppelin, by contrast, knew hippie culture intimately, loved the Incredible String Band and early Joni Mitchell and respected the romantic ideal of early Haight-Ashbury and drew on it in many ways. And John Paul Jones arranged Donovan’s great psychedelic albums including Sunshine Superman.

While you’ve written other books, this one, although it includes some of your memories of 1967, is less autobiographical and more an historical survey of a pivotal year. You did research and conducted interviews for it. What motivated you to take on this subject so seriously, and how long did you work on it?

I have long felt that most histories of the sixties, both film and literary, focused so much on protest that they neglected or marginalized the spiritual and cultural aspects that inspired me equally as a teenager. Late in 2015 my lit agent told me that there might be a market for books about the 50th anniversary of 1968 and I had an immediate visceral reaction that it would be a great shame to neglect 1967 which, to me, is the peak hippie year. So much got a lot darker in 1968 and thereafter. I started right away and was finished by November, 2016 so it could come out for the fiftieth anniversary of the Summer of Love, so it took a little less than a year but it was a year when I had to be very focused on researching and writing in order to get it done.

What’s the most hippie thing that’s ever happened to you?

Prior to Thanksgiving, 1967 I was in the San Francisco airport about to fly home to NY to see my family . I was barefoot in the airport, and told by the airline official I couldn’t board without shoes. I looked around the terminal and spotted a young guy with long hair, told him of my predicament and asked to “borrow his shoes” which he immediately gave to me. We were instant brothers in a spirit that was very real for the moment.

You describe the culture of 1967 as feeling like you were all taking a trip together, with “All You Need is Love” for your soundtrack. Do you think this was comparable to a mass experience of cosmic consciousness?

There was a brief period where I think there was a mass counter-culture consciousnesses. The closest thing to it in later years that I experienced were a few spiritual discussions led by Ram Dass and some Grateful Dead concerts, but even they were more limited and circumscribed than the mass community that sprang up, and for a brief time could use the words “peace and love” without irony.

You knew Timothy Leary during the later part of his life. Can you share with us a moment you shared with him?

I met Tim in the eighties and immediately took a liking to him. By that time the struggles of the sixties were behind him and he was unpretentious, friendly, and brilliant. When he found out he was dying in 1995 I was running Mercury Records I went to see him and he immediately said “Let’s do a project,” and we agreed to do an album and a documentary. While I was there William Burroughs called him. Afterwards he said to me “If there is one person I thought I could count on not to be sentimental about my dying it was Burroughs but he was blubbering and telling me how much he loved me. ” So did I.

You’ve known Ram Dass for many years. Can you share a personal story about him characteristic of his wisdom?

He still says “be here now”and he still means it. I asked him if he thought that the sixties culture he was part of had more light than darkness and he said he believed it did. But he also said that he and others had underestimated the polarity caused by the counter-culture and feels that some of that reaction helped create the climate for Trump. His guru told him to love everybody and he says he still aspires to that. One way he does it is by having a photo of a Republican on his puja table–now its of Trump.

Do you think that the internet is a help or a hindrance to the idea of hippie, that is, to agape?

Its neutral and can be used either way. The internet is external–love comes form within.

What was in your opinion the greatest good and the greatest bad to come out of 1967?

The greatest good was a mass awareness of the inner world and a broadened effort to make love a priority over materialism. And the greatest public figures in my view were Martin Luther King and Allen Ginsberg. The worst was widespread use of heroin and speed, co option of external hippie symbols by corporations and predators, and the violent reaction against the counter-culture by the government. Within the counter-culture the worst thing was tribalism that led to so much infighting that Che Guevara said “when you ask the American left to form a firing squad they get into a circle.”

What gives you the most hope in 2017, and what concerns you most?

My hope is based on an awareness that we have gone through worse times before as a country and love and morality have persisted and incrementally grown in influence. My biggest concern is that we will forget that and resort to counter-productive negativity.