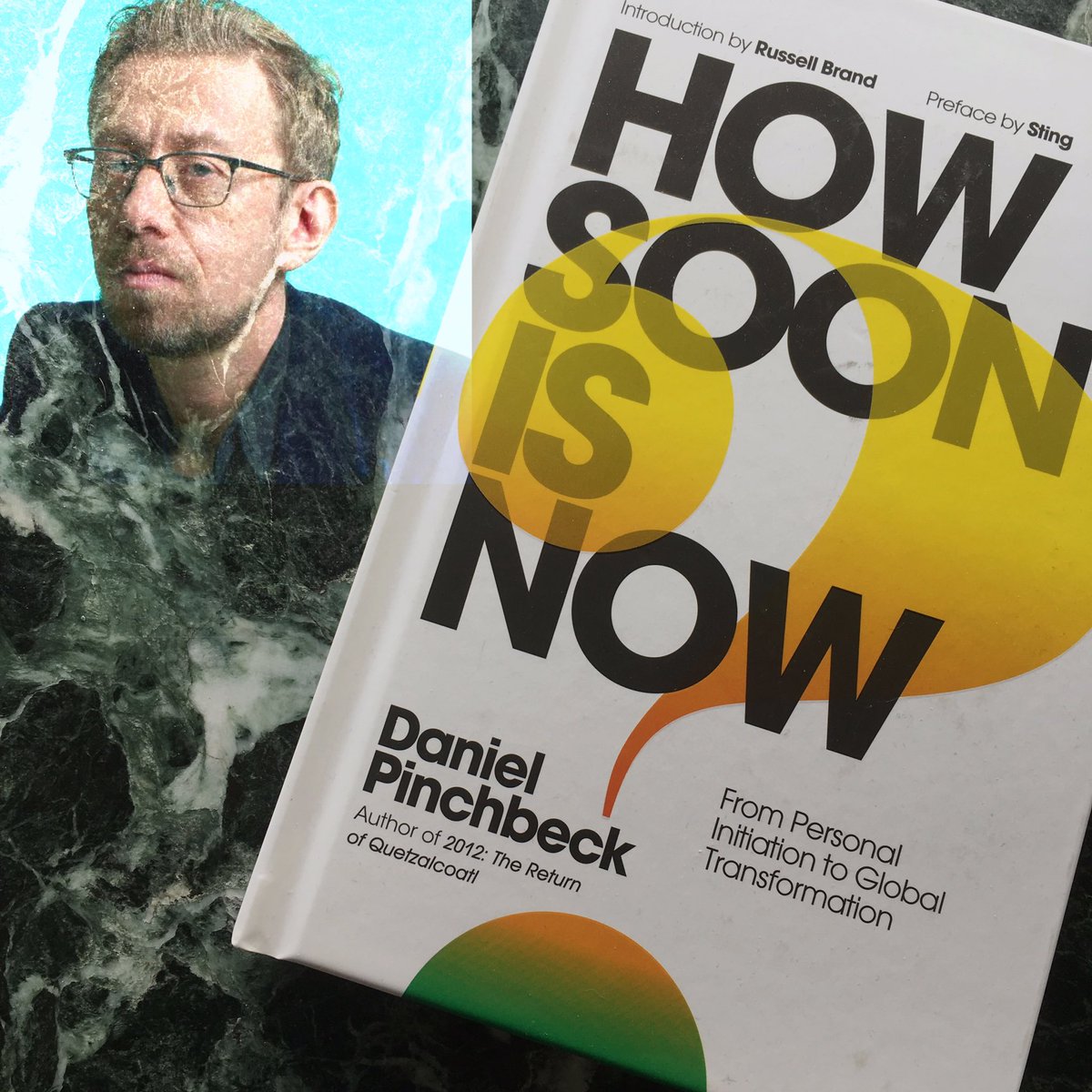

After his decade of research about the probability of imminent worldwide catastrophe and the people who are working to avoid it or at least survive, Daniel Pinchbeck’s new book How Soon Is Now: From Personal Initiation to Global Transformation is a terrifying yet exhilarating guided tour through what may be the most dangerous case of mass denial in human history.

Over the last ten years Pinchbeck has participated in Occupy Wall Street and wandered the streets of Paris à la Guy Debord with Alejandro Jodorowsky. In Colombia he studied the rituals of the Kogi and Arahuak. In a chartered copter Pinchbeck flew over crop circles in England with Sting and his family. In a geodesic dome in Utah he debated Russell Brand. In Palo Alto, California, Pinchbeck helped organize a climate change summit at Facebook headquarters.

How are the elite handling the fact that life as we know it may be about to change drastically? Pinchbeck provides this simultaneously inspiring and chilling example:

I write this having just returned from New Zealand where I attended a futurist conference organized by two young tech geniuses, in their early thirties, who dropped out of Harvard ten years ago to build a massive data processing company, which they sold for a fortune. With the proceeds, they acquired 2,000 acres of Kiwi forests and dairy farms. They are integrating the most up-to-date methods of organic agriculture, food forestry and solar-powered villages, assembling a dream team of yogis, reiki healers, permaculture designers, and software engineers. They chose New Zealand, after surveying the options, as the most likely place in the world to survive runaway climate change, global social breakdown, and everything else that’s coming. They may be the smartest people I know.

But what if instead of a fortress, survival experimental communities like this might be the proving grounds for a better future? Pinchbeck is far from a pessimist. He believes that humanity has manifested this crisis to force our own evolution. It’s a human characteristic to let things slide until the emergency becomes unavoidable, and what are such emergencies but invitations to greater consciousness and conscience?

Mainstream media has not given this book the attention some of his earlier works enjoyed. That might be because he had the courage to begin the book with a confession. What became the book began during a drug trip at Burning Man that inspired the author to take the stage to declare a messianic vision. Among other things he wanted to immediately create at Burning Man a massive coordinated effort to address the most dire problems of humanity. One can imagine straight-laced media types getting uncomfortable reading this despite Pinchbeck’s self-deprecating humor. When he became as Colbert put it “another Timothy Leary,” people of all walks of life wanted to tell him their psychedelic experiences, but this book presents a more somber expertise.

Is the problem that the messenger, a long time explorer of the cultural edge, is just too out there for coverage in Trump’s America? Or is that these issues are so overwhelming, the statistics so horrifying, that when confronting them denial becomes automatic? What parent wants to consider the possibility that life as we know it is about to end? What does it do to our comforts and our ambitions when we are told that many millions will almost certainly die off, and that the culture to which we’ve grown accustomed for generations probably won’t survive? What about the inadvertent message that the generations now and most recently inhabiting the earth may be the most irresponsible in history, almost certainly to be looked down upon as monstrously selfish?

To complicate matters, ever since the election of President Trump the daily news is so full of reasons for outrage and despair that it’s hard to keep the big picture in mind. Threats to health care, assistance and education, threats to what little ecological protections we employ, and to our liberty, along with disturbing scandals and shocking violence, fill our feeds. The existence of such a thing as a fact is questioned, and alarms are sounded weekly that the country is on the slippery slope to fascism. Perhaps this helps us ignore the more enormous problem. Maybe worrying about Trump is a relief when compared to contemplation of the terrible consequences of blind greed and irresponsible destructiveness. It’s easier to ignore the absence of honey bees and monarch butterflies in the garden when you’re arguing with trolls about politics. You might even be duped into thinking you’re doing something about it.

In this book Pinchbeck provides a comprehensive survey of all the ways petroleum man is wreaking havoc on the environment. He examines the hope and doubt engendered by such partial solutions as renewable energy, ride sharing, and scientific and technological breakthroughs. He asks us to consider the difference between shifting entirely to renewable energy in fifty years versus ten years. How could humanity mobilize to accomplish such seemingly impossible goals as revolutionizing energy infrastructure? Pinchbeck suggests that perhaps the answer is as near as Facebook and Google.

While many dismiss Facebook as qvetchbook, or a mere platform for advertising, Pinchbeck explains that Facebook is more like a utility. The Trump campaign and Cambridge Analytics demonstrated the power of using Facebook to connect people. Pinchbeck believes Facebook itself could champion a sort of moonshot orchestration of public opinion by providing accurate information and the tools people need to get organized. Events like the Women’s March and the Arab Spring demonstrate the potential power of social media networks.

More traditional institutions could also provide opportunities for faster education and action. Pinchbeck wonders what would happen if the Catholic Church truly embraced the environmentalism of the Pope? The most traditional and the most innovative institutions together could provide the infrastructure for people to organize. What if television, film, the internet and politics fostered community and empathy instead of being devoted merely to profit and trolling?

Reading How Soon is Now I was reminded of the Whole Earth Catalog, which was a kind of paperback internet for hippies, providing contacts to all the latest innovators. I found myself hoping for an online directory to all the worthwhile efforts Pinchbeck describes, a way to make it easier to support or to just follow the progress of the people working on answers to the most difficult questions.

In this way, Pinchbeck suggests, a group of early adopters could organize improved models for necessary breakthroughs. That demonstrated superiority could then win over enough converts to make the change. He describes a new kind of corporation organized not for profit but for achievement of common good. He highlights the amazing potential of blockchain to revolutionize everything from financial systems to voting. He wonders why with today’s new technology an election couldn’t happen whenever the majority suffers a crisis of confidence. With modern tech why couldn’t a Trump be voted out and a Bernie Sanders be voted in if that’s what the majority of us really want? Why must we be trapped in manipulated voting technologies and archaic terms of office?

Pinchbeck also explores the idea of moving past monogamy, suggesting society could heal gender issues and create a more natural interaction. Many men, he points out, exist in systems of competition where the winner allegedly has the best selection of mates and where wives must be jealously guarded to insure the passage of possessions from father to child. What if men didn’t have to win women by driving fancy cars and having fat bank accounts? He adds that child care and elder care must be part of the gender New Deal.

Personally, I like Pinchbeck’s original idea at Burning Man, too, a Festival Earth where holy people pray down the vision, eggheads work out the plans, while artists of every kind record it all for posterity, and bands and other sound makers provide the march music and ambiance; that would be quite an event. Meanwhile let’s hope that a documentary or perhaps a documentary series is in the works, as the horrible threats and hopeful opportunities captured in this book, need to be more widely shared and discussed.