This story was previously published in Fiddler’s Green Peculiar Parish Magazine.

When I was young, there was a tree…

It was probably dead by the first time I noticed it, but I am not sure. That was a long time ago. If the wind blew in the slightest, this old tree would moan and creak like some ghost ship lost upon the heaving sea. However, even when the air was still, it seemed to issue eerie sounds whenever I passed by.

The tree was perhaps an eighth of a mile downhill from the farm where I grew up, a few feet from the road, up a bank and just at the edge of a trail-less section of woods. These were the 1970s and, though it may be somewhat difficult to imagine now, I was allowed to roam the rural neighborhood by myself from a very young age. I have memories of being as young as six or seven years old and walking through the woods and fields or along the rural roads by myself.

I could not have been much older than that when a boy named Mike, who lived up the road and was some years older than I, said to me, “Do you hear that creaking? That’s the Witch Tree. They hanged a witch on that tree. Her soul is trapped in the tree. That creaking is the witch saying her spells.

I have never been short on imagination and I seemed to have a preternatural ability to summon the strange and the frightening from shadows—to terrify myself, if no one else. That said, I have also somehow been given the ability to—not so much overcome these fears, be they self-made or other, but to force myself into them—sometimes to the point of rather enjoying the sensation.

That being so, I was prone to such thoughts before this older boy ever put these images of hanged witches and trapped souls into my mind. Imagine, then, how this figured into both my conscious and subconscious. Where I listened curiously before, now I would speed up whenever passing this tree. Where before I heard creaking, I began to try to make out words—or to imagine the witch’s soul chanting in eldritch tongues. Those times I had to pass the Witch Tree at night, I would hold my breath and try to move as quietly and quickly as possible, so as not to draw the witch’s attention.

Of course, I know a person was not likely hanged from that tree—for witchcraft or for any other reason. That said, I don’t know if Mike made up the story of the Witch Tree himself or if he was just passing along folklore he had learned from someone else. As time went by, perhaps because fewer children roamed this rural road, the legend seemed to pass from folk memory. When I asked around years later, no one seemed to remember much about the Witch Tree. In recent times, when I talked with one of my brothers about it he said, “Oh yeah, that old tree you used to be afraid of…” as if he had not thought about it for decades. He could recall nothing else about the haunted tree. It seems that I alone carried the Witch Tree in my memories.

It is strange indeed to have such a thing take an important place in my memory. It certainly held that place in my youth, for I became somewhat entranced by this tree, this haunted tree that was based not on a historical event, but just on some story, a story that never happened. Perhaps it was even a lie that one child told to a younger child in order to frighten him. It’s not something that would have been out of character for Mike. When I was a teenager, he snuck into my house as I was sleeping and leaned over me, flicking my ears and frightening me awake. I punched Mike out that night—a clean strike to the jaw which put him flat on his back. He never tried to frighten me again.

There was a bit of the Trickster in Mike, and I now forgive him for doing what was in his nature to do. He could be mean at times. He could be cruel. He could be a bully. He could also be a lot of fun and he did always seem to have a story. Mike gave me the Witch Tree. Whether it was of his own invention or something he simply passed on to me, he gave it to me and I did not take the gift lightly, then or now.

Even if no one else much cared about the Witch Tree, or if they brushed off the story as nonsense, I took it to heart. Looking back, I now wonder if I ever really believed the story was based in fact or if I simply willed it to be true with such pure, youthful desire that it began to become real in my youthful mind. On hot summer nights I would lie awake in bed straining to hear the Witch Tree through my open window. It was too far away to hear from the farmhouse…and yet what was that creaking, squeaking moan? Was that a whisper?

Every Halloween I would find myself drawn to the tree. With short breaths and quickened heart, I would push myself step by step down the hill wondering if I would faint should something move in those woods, or should the creaking become angry, or intelligible. There was so much to fear, in my mind, and yet I made myself go to her.

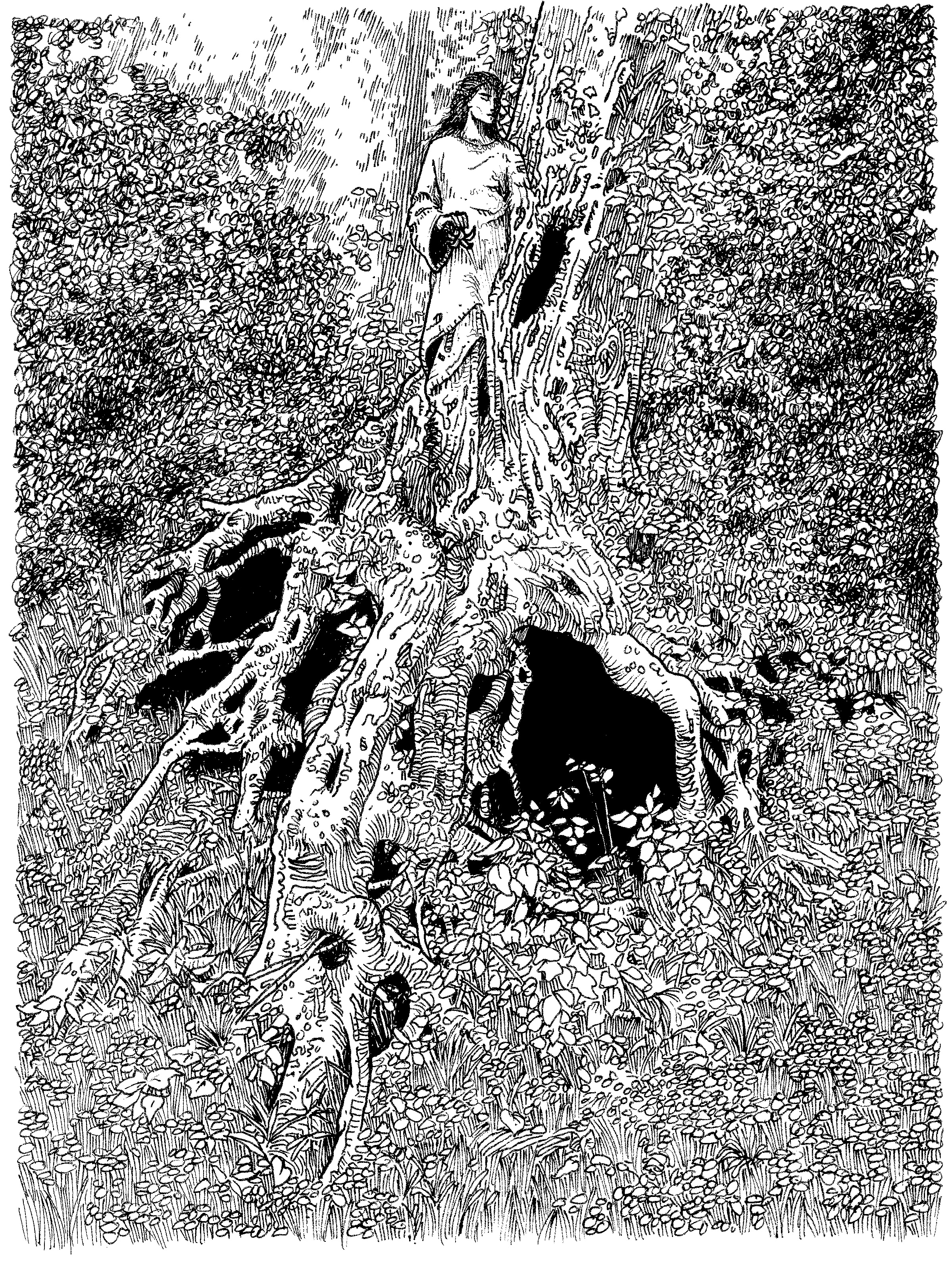

Yes, her. I had well personified this tree. This witch trapped in rotten wood. I knew her—or more accurately, she knew me. She knew when I walked down the hill. She knew when I thought about her. She knew when I visited her. She knew when I didn’t. I never gave her a name, because her name was not in the story Mike told to me. She was simply “the Witch.”

Witch: I’m sure that word conjured particular images for most children—storybook women in black, with warty noses shaded by pointed, wide-brimmed hats, stirring steaming cauldrons—or perhaps the green-faced Wicked Witch of the West, from Oz, cackling on her broom. To me, the word “witch” would call to mind images of that old tree—with some kind of strange old bony thing trapped fetus-like in its trunk, always chanting in cracks and creaks, always squeaking and moaning, always trying to scratch her way out.

For other children, witches came from haunted houses or dark castles in faraway lands. My witch was a neighbor in a dark patch of woods.

::

For what it’s worth, I lived on an old rural route renamed sometime after my birth as Dark Hollow Road. It was so named for the dark valley that cut through the rolling hills by way of a winding creek. Dark Hollow Road lived up to its name. It could be a strange place. The Witch Tree was in that dark hollow. I saw ghosts in our old farmhouse, not as a child but much later. I did see a UFO there as a child, hovering above the trees for hours. And though I never saw it myself, other people in the neighborhood reported seeing a large black panther on several occasions. Some of my earliest memories involve a recurring something—perhaps a hypnopompic state, perhaps a vision, perhaps the wild imagination of a child, or perhaps something else entirely—but I remember waking up, before anyone else in the family, literally paralyzed by fear, and hearing voices speaking a language I did not understand. I came to the conclusion, somehow, that these disembodied voices belonged to three witches—who were in the room below my bedroom. These witches came years before I heard the story of the Witch Tree and I do not believe they are related, except in that hazy fog of the strange where all of these odd things seem to be related by some tenuous and uncertain web.

In my book, Beyond the Seventh Gate, I note how weird things—cryptids, ghosts, mystery lights, and anomalous animals—often seem to be seen around creeks, streams, springs, and rivers. I wasn’t the first to recognize this pattern. For those keeping track of such things, as I now do, there was a creek that passed close by the Witch Tree and arced around the back side of the farm, marking the border of our property on the east side.

In the book, I go to some lengths to clarify the historical truth behind some legends from York County, Pennsylvania, where I now live. It was very important to me to set the record straight. I believe this is valid. If someone is supporting their stories by making up fake histories about supposedly haunted places, I believe it is important to document the truth, which, as the old adage goes, can often be stranger than fiction.

There is, however, another side to this coin, a side that has been scratched and worn and obscured so that the original text and dates are unreadable. New text and weird symbols have been carved over what was first stamped into the coin. This is where we get into even stranger territory. There are many ghost stories based on things that never happened, or on unprovable legends. This happens in every town, I’m sure. Stories twist and turn as they get whispered from person to person; they take on elements of pop culture or change in reaction to social issues of the time. This is a natural part of storytelling. This is folklore. To me, however, things get more interesting when, no matter whether the stories are based in fact or not, people start experiencing odd and paranormal things relative to these places. There are, for example, stories of people seeing ghosts of supposedly “real” people at haunted sights after historians have proven that these people never existed.

It’s as if all the concentration and energy people have put into these places has made them haunted. This gets into the hazy territory of the tulpa and the egregore—concepts requiring entire books to explore fully, but which can be boiled down to the term thought-forms. Could it be that all of the concentration on these places has made them haunted—not by the souls of the dead, but by thoughts somehow manifest in the physical realm, however faint and ethereal? Could it be that the children of Dark Hollow Road somehow willed a witch into that dead tree?

Childhood is by nature a liminal state—kids are neither baby nor adult. Roads, too, are liminal places—neither here nor there. It often seems to be that supernatural activity is experienced in liminal states and locations. The Witch Tree, beside a creek, beside a road, was the object of the local children’s attention and the near obsession of at least one child. The parts were all in place. The ghost assembled itself.

I wish I could tell you I saw shadows move around that tree, or that I heard clear, audible speech; perhaps that I saw strange lights dance around the trunk or horrible screams issue from the woods where it was rooted. The truth is nothing so fantastic or dramatic. The truth is I listened to creaks and moans issue from that tree for many years. I tried to make them into words, but the witch’s language was lost to me. The truth is, I was scared of that tree for a long time. However, with time things seem to change.

As I aged into my teenage years and adulthood, I knew logically that a witch had not been hanged on that tree. I visited her less frequently, and thought of her only on occasion. But I did still think about her, and I did still visit her. The Witch Tree had become a place of power to me, a place of meaning.

It does not matter that a witch was never hanged from that tree. The truth is that Mike, or whoever told Mike the tale, placed a witch inside that tree. Both tale and witch grew roots through my mind and into my heart and filled my childhood with fear and excitement, eventually leading to a kind of mystical connection between trees and souls in my mind.

There was a tree. It stood along Dark Hollow Road, at the edge of the woods, just up the hill from the creek. These things are true, even to those who refuse or do not care to see anything more.

To me, it was much more than just a tree.

::

Some fifteen years ago or more, as I was driving to the farm, I saw that a tree had fallen into the road. As I came closer, I saw that it was the Witch Tree. A great sadness came over me. The Witch Tree had been dead for years—I knew she would not stand forever—but it was still a shock to see her prone by the road. She seemed so exposed outside the tree line.

I went to visit her one last time. I realized that I had never actually gone up the bank, had never actually touched the Witch Tree before. The fear of my youth had turned into a kind of reverence in later years. It seems fitting now. When the tree was standing, it was something weird and other having taken physical form. I had no business touching the other. Now that she had fallen, I looked more closely.

I picked up some splintered wood that had broken off of her in the fall. It was colored a deep blue-green. Some people call this “blue wood”—it is also known as “green stain” and comes from a certain wood fungus. I would later learn that this blue wood is prized by some woodworkers—and is often used in inlay work. I took two pieces of blue wood from the Witch Tree. I have one. My musical partner Prydwyn has the other. The rest of the tree was eventually hauled off, unceremoniously, by some county road crew. They knew nothing of the magic they carried away.

Up the bank, a hole was left where the roots of the Witch Tree once were. Beside the hole was a single black feather and an empty whiskey bottle. I considered taking these items, but it seemed to me as if they made some sort of shrine. Whether they were placed there with intent or found their way there by chance didn’t matter, just as it didn’t matter whether or not a “real” witch was hanged from that tree.

After my last visit to the Witch Tree, I met my brother at the farm. He told me that Mike, who had been suffering from Lou Gehrig’s disease, had died the night before, the same night the Witch Tree fell.

The Witch Tree has fallen. The Witch has been freed from her earthly prison. The piece of blue wood I took from her sits in my studio, the place where I sing songs and make art. I look at it often. I pick it up, and I remember.