This will be about Anne Waldman’s new book of poems, Trickster Feminism, but I want to begin by looking at the background, the context for the emergence of a contemporary poetry of consciousness, of which Waldman is a master. (Throughout, I have punctuated the text with lines from the book, which appear in italics.)

In the introduction to their epochal anthology Poems for the Millennium, Jerome Rothenberg and Pierre Joris feature a quote from the visionary poet-painter William Blake as indicative of an intuition that persists in some of the poetry our own time: “poetry fetter’d, fetters the human race.” If this is true, then the inverse is also true: freeing poetry frees humanity. Allen Ginsberg, himself a scholar of Blake, put it as follows. “A change of poem is a change of mind.” From Blake’s time to the present, the idea has persisted that new forms of language convey new forms of consciousness and can thereby reinvent reality. It’s a romantic notion, but that doesn’t mean it’s wrong.

Thank you poets./ You rescued our minds./ Turned grief into tenderness./ Into a world of tangible things.

For example, at the most basic level of political history, it is practically a cliché to refer to the United States, say, or to the French Republic as “an idea,” in other words, a thing made of language. Free speech makes free nations. The words of Thomas Jefferson kicked off the American Revolution, and the words of Thomas Paine sustained it. Words matter: they have material consequences. The ancient roots of poetry in ritual magic were not mere superstition. We still, now, at every moment call our world into being in and through language. In 1980, Julia Kristeva wrote of “the determinative role of language in the human sciences” as an idea that came to prominence in the post-World-War era, but the idea of language as determinative of reality goes back to the book of Genesis, “and God said,” and the creation hymn of the Rig Veda, where the first poets “found the bond of being within non-being with their heart’s thought.”

What shape, body?/ with what do you inspire devotion?/ how do you construct existence?

In his book The Birth of the Modern Mind, Paul Oppenheimer argues that the invention of the sonnet in the 13th century was evidence of a new mind, a new self-consciousness. The sonnet was the first poem intended to be read silently. The dominant poetic forms of the period were made to be sung in public, but the sonnet was a meditation to be conducted in private. It’s about how “I” feel. It’s a wonderful form capable of containing great beauty, but it is also indicative of the emergence of the isolating narcissism that laid the groundwork in consciousness for the emergence of capitalism. We might say that in order for there to be private property, we first had to invent privacy. The triumph of capital came, in terms of consciousness, in the establishment of the unquestioned and universal sovereign self, every home a castle and every man a king.

In the 1940s, the literary theorist Mikhail Bakhtin championed the novel for its democratic, inclusive nature in representing all kinds of people at every level of society, and decried poetry as the aristocracy’s celebration of itself. It is true that what we might call the poetry of “I feel” has presented a strong through-line from the Renaissance to the present, but it is also true that different strains emerged. It is to these that Joris and Rothenberg refer in their Poems for the Millennium.

In the twentieth century, in the USA in particular, there was a shift in poetry away from the sentimental expression of personal feelings and toward the observation of mind, a change of subject from emotions to consciousness. It was not universal, of course, and the poetry of feelings (“confessional” poetry is the conventional term) is still with us, and in many ways is still dominant in those popular media that still present poetry, but beginning in the 19-teens there emerged what was called Objectivism and Imagism, which prioritized, in the words of Ezra Pound, “direct treatment of the thing,” the presentation of the perceptions versus feelings, open form, and an experimental approach to language. In a sense, the subject of poetry became not the self, but language itself. It was in part a reaction against the romantic excesses of the symbolists, and much of it was influenced by Asian sources — for Pound, Confucianism and ancient Chinese verse, and for key figures in the subsequent generation, Buddhism.

Buddhism initially came to the west in the nineteenth century through the writings of missionaries, scholars and colonial officials. It influenced Schopenhauer (1788-1860) as well as the American Transcendentalists and was praised by Nietzsche (1844-1900). The first known Western converts to Buddhism came in the 1880s. Chinese laborers established temples in America in mid-century; in 1893, a Japanese delegation to the World Parliament of Religions included Zen priest Soyen Shaku, and in 1899, Japanese immigrants established the Buddhist Missions of North America. The event that would prepare the way for the widespread influence of Buddhism in America came in 1897, with the arrival of scholar D. T. Suzuki, a student of the aforementioned Soyen Shaku, who would prove to be the most important bearer of Zen to the west. Suzuki’s lectures at Columbia University (1952-57) were attended by emerging figures of the New York Avant-Garde, including John Cage, the Beats, and the New York School painters and poets.

Jack Kerouac popularized Buddhism with his novel Dharma Bums (1959), the hero of which was based on west coast poet Gary Snyder, who had taken Buddhist vows in Kyoto in 1955. In 1959, Zen master Shunryu Suzuki Roshi arrived in San Francisco, attracting many followers among the artists and writers of the area. Alan Watts’s 25 books had an impact, particularly The Way of Zen (1957), which was a bestseller. Following the Chinese crackdown on Tibetan resistance in 1959, a number of Tibetan teachers began coming to the US, and in the 1970s a number of Tibetan Buddhist centers were established. In 1974, Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche established the Naropa Institute in Boulder Colorado as the first Buddhist college in America, and his students Allen Ginsberg and Anne Waldman, and Diane Di Prima, who studied with Suzuki Roshi, founded the writing department at the school.

It was not serendipitous that the turn to a poetics of consciousness coincided with the importation and spread of a spiritual practice based in the observation of mind. Thus San Francisco poet Philip Whalen, who became ordained as a Zen teacher in the lineage of Shunryu Suzuki, wrote in 1959, “This poetry is a picture or graph of a mind moving.” The movement of mind is the subject of the poem, not reflection on oneself. The poem is not about me; it’s about consciousness. The thought is the thing, not the thinker.

I once heard a Buddhist monk from Bodh Gaya say, in answer to a question about meditation as a way of finding oneself, “To search for the self is to look for a black cat in a dark room in which it is not.” In a similar vein, Nietzsche had dismissed the doer in favor of the deed before the turn of the 20th century. “There is no ‘being’ behind the deed, its effect and what becomes of it; ‘the doer’ is invented as an after-thought, – the doing is everything” (Genealogy of Morals section 13).

The thinker as after-thought invokes a question Allen Ginsberg used to bring up when looking at students’ poetry: “What were you thinking before you thought you were writing a poem?” It was an extension of his teacher Chögyam Trungpa’s “first thought, best thought” and William Blake’s “First Thought is Best in Art, Second in Other Matters.”

Mind moves; self is a retrospective construction. Charles Olson, writing in 1950, emphasized the importance of the poet realizing that one thought is followed “instanter” by another. “One perception must immediately and directly lead to a further perception.” The job of the poet was to keep it moving. It was a dynamic age. The Futurists, beginning in 1909, had championed a new beauty: speed. By Olson’s time, even the most static of forms, painting, had become “action.” Jazz is another case in point. In its most characteristic moments, it is invented in flight. In the 1960s, the last vestiges of established form were jettisoned altogether in “free jazz.”

All of this harkens back to art’s origins in shamanism, ritual, and performance. 20th century poetry saw a performative turn, specifically in the return of poetry to the voice. After 500 years of poetry as a largely private, silent practice, we had an aural renaissance, beginning in San Francisco in the 1950s, and soon carried to New York with the Beats. With the return of performance came, in various ways in various artists, a return of the sense of the spell, or the sense of poetry as ritual purification, transcendence, and change. For some, it was subtle, a kind of humorous self-deprecation through serious play; for some it was a troubling of established forms linked to a revolutionary agenda; for others it was quite consciously magical incantation; or it was some mix of all of the above.

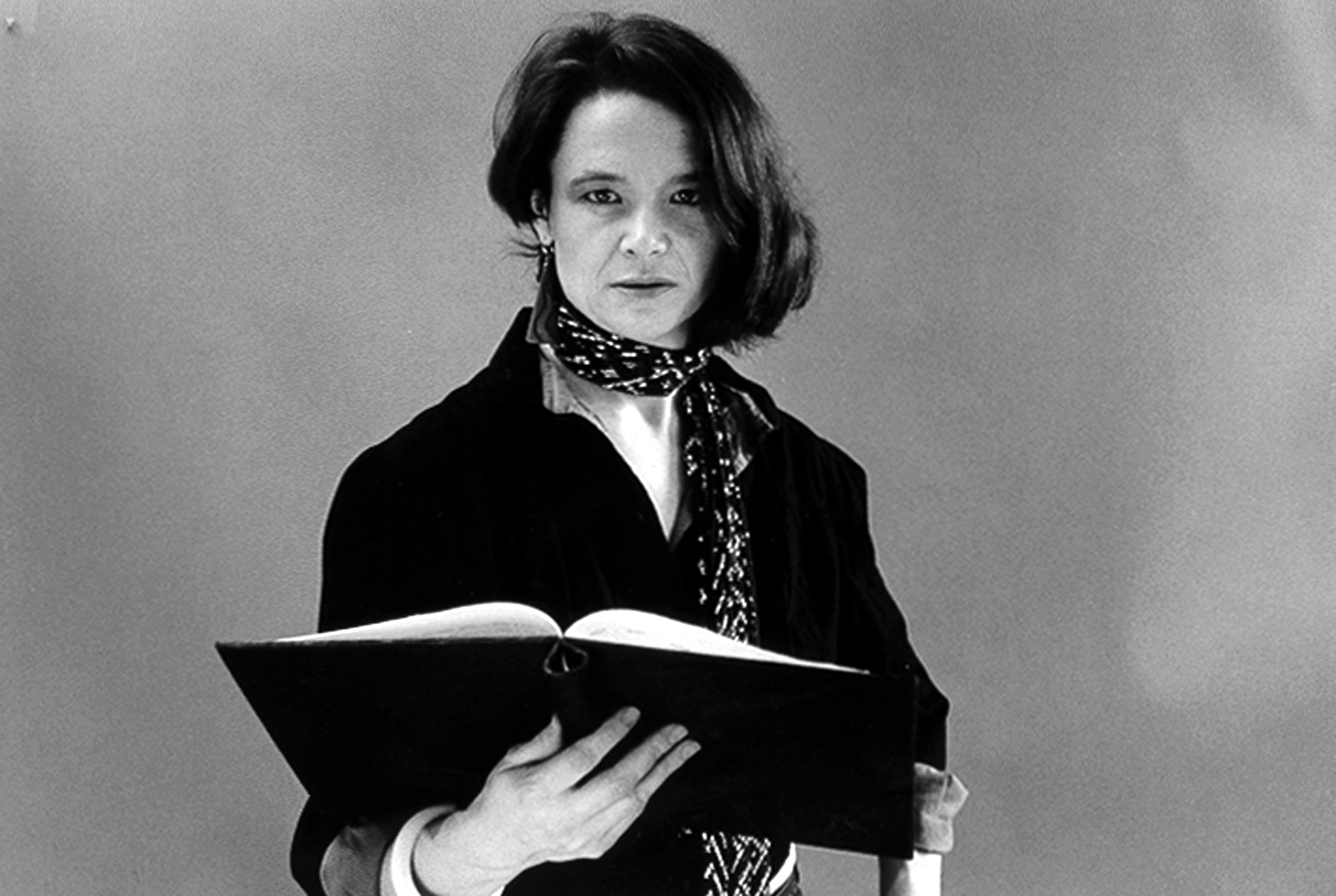

This brings us to Anne Waldman, one of the most dynamic bearers of the lineage of the Objectivists, Beats, and New York School. As one reviewer has noted, “Waldman’s work is the antithesis of stasis. . . . She is a flame.” Her bibliography lists more than fifty books and pamphlets of poetry. Add to that the anthologies and zines she has edited, the recordings, the performance works and videos, decades of international touring and teaching, her activism for peace and justice, and her co-founding of the Poetry Project in New York in the 60s and the Jack Kerouac School of Disembodied Poetics at Naropa in the 70s (both of which she directed for decades), and she appears as a formidable force in the new American poetry of the past half century. And she’s still cooking. Witness the latest book of poems, Trickster Feminism, published in 2018 by Penguin.

Allen Ginsberg called Anne his “spiritual wife.” She is a lineage holder in the Beat, New York School, and Black Mountain streams, but she transcends these because she draws strongly upon feminism and practices poetry intentionally as shamanism, and because she has made her own way.

By way of perspective on how it was to emerge as a woman artist in the mid-twentieth century, I recall hearing the late great Joanne Kyger (also a long-time Buddhist) say that when she became active in poetry circles in San Francisco in the late 1950s, she was told that it wasn’t possible for a woman to be an artist because an artist is a lover of the muse and the muse is a woman. Apparently the possibility of love between women didn’t figure in that view. I also remember a panel discussion about the young Beats and related movements in mid-century poetics, all of which were pretty much boys’ clubs, and someone asking why there weren’t many women, and Gregory Corso saying there were women poets on the scene, but their parents had them committed to insane asylums. Of course there were exceptions, and these cases seem extreme, but they do speak of the obstacles facing women in the arts of the period. Of the circles most influenced by Buddhism, the main female figures are Waldman, Di Prima, and Kyger.

Lyn Hejinian said of Anne’s book Voice’s Daughter of a Heart Yet To Be Born (2016) that it “brings Waldman’s work into the more intimate paradoxical folds of poetic (and prophetic) knowledge.” Her new book Trickster Feminism is of the same stream.

Where there is oppression there is paradox. Trickster feminism is a mode of disarming paradox by performing it. It’s a both/and-neither/nor ontology. It is trans-genus.

No fixed feminine, no fixed constituents cut through this body of difference. . . . Your wounds, your hurricanes, your artifacts. Identities to get by. Genders try you on.

Trickster feminism is a mythology, as in a deconstruction of myths, or a mythos that recognizes itself as such. According to Claude Lévi-Strauss, who analyzed hundreds of myths from indigenous and folk traditions, the function of myth is to reconcile a paradox. Many myths do this by invoking a trickster figure. Apparently irreconcilable opposites like life and death are reconciled in a trickster such as Coyote or Raven; they embody the paradox: they make life out of death (they live on carrion). I would add that Jesus, too, is a trickster; he makes life out of death. Donna Haraway says tricksters are like angels, or like mucous; they occupy the in-between spaces and grease the works. Got lube? It’s all metaphor. What isn’t? Material reality, the suffering of sentient beings. Poetry begins as relief of suffering through magic. What we call world is word magic. Change the words, change the world.

What myth is structuring my imagination? The end of democracy? . . . Take back founding myth of Americas: evil of the Feminine.

This poetry is a mind moving. It shows you your mind unstuck and wily like a coyote, or slippery like an angel, that’s the delight in it. Just don’t get hung up on your feelings. The poet and novelist Bobbie Louise Hawkins used to tell her students, “nobody cares about your feelings, darling.” It’s not that your feelings aren’t important, but that’s not poetry. That’s why so much of the poetry in so many of the magazines is not poetry. Trickster Feminism is poetry. As the poet Lee Ann Brown said to me in another context long ago, “better git it.”