“Temples that roar with thunder…statues that cry tears of blood…chariots that levitate in the air–these were the machines of the gods.

In ancient Alexandria, Greek temples employed complex, highly sophisticated machinery to create illusion and magic. At their core, temples were theaters that produced spectacles–not of drama–but of mystery. The competition was fierce amongst the many religions, let alone the other forms of entertainment, to draw in crowds. This required a magician’s touch that could make the unbelievable happen.

Thus, the temples funded one of the greatest inventors of antiquity, Heron of Alexandria, to create the most stunning machines to awe and terrify the congregates. With technological feats as spectacular as the temple machines that Heron produced, they give us fascinating and astonishing proof of how technologically advanced the ancient world was.

Alexandria: The Pearl of the Mediterranean

Alexander the Great founded the city of Alexandria in 331 B.C.E around a small Egyptian Mediterranean port town that dated back to 1,500 B.C.E. The city grew to become the second most powerful city in the empire, next to Rome, with one of the largest ports on the Mediterranean coast. The Lighthouse of Alexandria– completed around 270 B.C.E.–remains on the list of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World.

A magnificent city, gigantesque Greek and Egyptian monuments stood together. Rich silks and fabrics from the bazaars of the Orient adorned its markets, the smell of exotic spices from Indian and Arabia perfumed the air. Traders and merchants carried a diversity of ideas and people from around the world to shore, which contributed to the city flourishing into a center for culture and learning.

Alexandria was “east meets west.” The ancient knowledge of the Egyptians met the Greek new world.

The city was world-famous for its enormous and exquisite library built, speculatively, somewhere in the first 4 centuries B.C.E. It housed the most precious knowledge from antiquity. The library drew some of the most brilliant mathematicians, engineers, artists, and academics of their time.

Feeding off this ancient knowledge, one engineer would become the mastermind of religious spectacles. With sophisticated gadgetry, Heron of Alexandria manipulated elements such as fire, water, and wind. He created illusions so mystifying that crowds flooded into the Greek temples.

Heron of Alexandria

Mathematician, inventor, mechanical genius–Heron of Alexander is the greatest experimenter of antiquity.

Heron of Alexandria lived somewhere between 10-70 A.D. As a student, Heron spent most of his education in the library at the University of Alexandria. Heron’s most famous inventions include the first recorded steam engine, a windwheel operating organ (first use of wind to power a machine), and a cuckoo clock – but none of these compare to the spectacle of machinery that he created for the temples.

First, Heron of Alexandria invented the vending machine, whose original function was to dispense holy water. One could call this “ticket sales” to the show. Thus, when an audience member entered the temple, they put their coin in a slot at the top of a simple water dispenser. The coin would drop onto a pan inside the device on a delicately balanced beam. The weight from the coin depressed one end of the beam. This would release the other end from which a small amount of water would flow out.

Greek Temple Magic

“Secretive mystery religions such as Isis were alongside more state religions, which are not so much about the magic and the gods than the maintenance of the status quo.”

At the beginning of the first century A.D., the meeting of worlds in Alexandria made for a fascinating array of religions that competed for the greatest number of worshippers. Alexander the Great’s successor Pharaoh Ptolemy I Soter had established Serapis – an Egyptian-Greek hybrid god – in an attempt to unify the two groups. Serapis had one of the most important and majestic temples of antiquity–and was one of Heron’s biggest clients. Nevertheless, there was room for everyone. In Alexandria, mystic cults met state religions, and the Christians were the new kids on the block.

“Temples were deliberately dark places. They were there to enhance a sense of mystery. They were places to go and get scared. To play on the hairs on the back of your neck.”

Chanting, prayers, the lighting of candles, the priests invoked an atmosphere in which to envelop the worshippers. In the rafters of the temple, thunder-making machines shook the temple making it roar. Wind-making devices, diamond-like objects hanging from the end of a string, would be wound up in the air. Whistling, spinning, and ominous winds would envelop the congregates.

Employing technical trickery, the priests invoked a mysterious atmosphere, communicated their authority and signaled the presence of the gods.

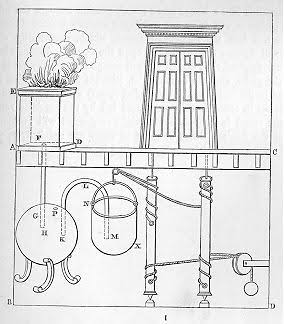

Heron of Alexandria would use the fire from the sacrifice to make the temple doors open and close automatically.

As the altar heated up, the fire would warm the air in a cylinder beneath it. That would force water into a bucket suspended by chains (this is all hidden). The doors would open as the bucket got heavier. As the fire burned out, the doors would then close as magically as they had opened.

Heron’s famous book, Pneumatica, is one of his writings on mechanics that we have left. Pneumatics is the method of using gas and air to move objects, a technique that Heron employed in his devices to achieve an otherworldly effect.

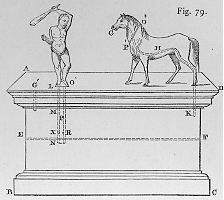

One of the most stunning machines is #78, an altarpiece featuring a stone sculpture of a cherub and a horse. The cherub would pivot to face the horse. With his knife, he would cut the head off the horse; the horse’s head was connected to his body by a telescopic pipe.

While the cherub turned to face the horse, water would fill a chamber below. The knife moved parts of the pipe apart, as it sliced through the horse’s head but it would also put the parts back together again. As the horse’s head would be falling over, the priest would put a bowl of water under the horse’s mouth. The pressure from the water filling up the chamber below would create a suction effect. Thus, the horse appeared to drink from the cup.

The gods were officially present.

At that period, priests were the keeper of secrets, and at the forefront of scientific discovery. Magicians or conjurers performed a stupefying role in interacting with the divine forces in the temples.

Using entrails, the priests employed chemistry to add an extra sizzle or crackle or a supernatural effect to the sacrifice.

According to historians, these mystery religions projected the worshipper into a state of not knowing. One cannot confirm whether or not the congregation was aware of what they were drinking and eating. However, plants were a key part of the ceremony.

“Logwood,” for example, when put into wine and consumed, dyes the person’s urine red. Then, once they stopped drinking, the urine cleared its color. Thus a malady could fall upon the worshipper, and the priests could cure it miraculously. So, priests were ringmasters, miracle-makers, and producers of theatrical events.

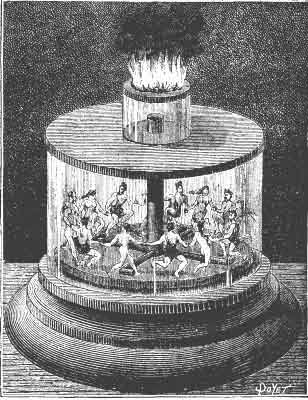

Under another altar, Heron constructed a kind of merry-go-round using the altar fire as a power source.

Beneath the altar was a transparent and circular case, covered in glass, with a few sculptures of dancing couples. The priests would be on top-performing the sacrifice. The heat from the altar flame moved down a central pipe. That pushed air into the supporting legs that turn the device. The air would come out of tiny holes in the floor of the case, each connected to a supporting leg. And, magically, the whole case would rotate. The dancing slowly came to a halt with the dimming of the fire.

Another device celebrated the mystic marriage between Mars and Venus.

Mars and Venus seated on either end of a bench, they were sculpted with two different kinds of metals. Initiating the device, they would begin to slide towards one another, but when they drew close, they would become so mutually attracted to one another that they “lept” into an embrace.

Perhaps the most astonishing mechanism was a flying chariot.

The ancients knew how to use magnetism. This is one theory that has been put forth to explain how the Egyptians built the pyramids, for example. However ancient evidence, Heron’s work, shows that they did employ magnetism to achieve unbelievable trickery in the temples. Still, the flying chariot was either dismissed or overlooked as a concept, until a Greek Historian paid closer attention.

Ioannis Arvanitis – ancient Greek historian – had long heard of the magic tricks of the ancient temples but, “…a flying chariot? Made no sense.”

Serapis, the state god that Ptolemy I had instated, was the god of the sun. The immense sculpture in his temple remains – though it was destroyed – legendary. At a particular time of the year, there was a slot in the wall in the back. At a precise moment, the sun would beam through the slot and light up the god’s face. Then, a chariot, Apollo as its eternal driver, would be magnetically pulled towards the immense and impressionable statue. When the chariot reached his feet, it would levitate into the air and hover about the god’s face.

Conclusion

In ancient Alexandria, temples funded mindbogglingly elaborate and sophisticated engineering techniques to allure, amaze, and frighten their congregations. The act of going to a religious ceremony was a theatrical event. Resources were allocated to create spectacles that would impress the feeling of awe, terror, and mystery onto the congregations. Heron of Alexandria masterminded the magic of the gods. But that does not negate the breathtaking engineering techniques used to stir, to cause an effect. Our sense that the ancient world was “behind” us, or employed less sophisticated technology, is proving to be incorrect. Furthermore, the theatricality of the event injects invention, innovation, and simply–fun–into the experience.

We participate in the creation of magic. We are divinely inspired. Though the gods did not directly generate the miraculous events that occurred in the temples, a man with the imaginative and creative power brought the gods to life.