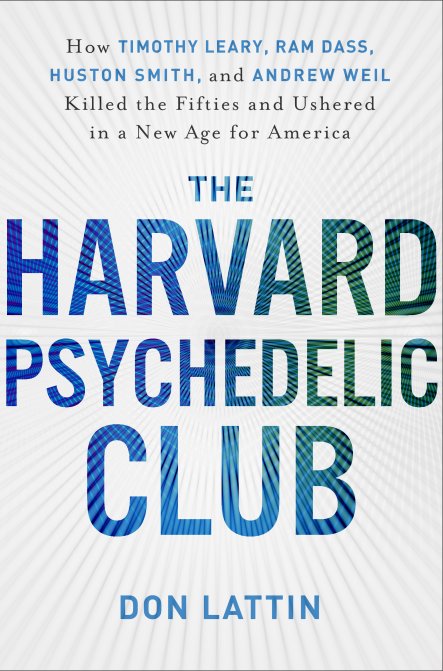

The following is excerpted from The Harvard Psychedelic Club available from HarperOne.

Huston Smith had come to MIT in 1958. He was thirty-nine years old and just hitting his stride as a scholar and commentator on the world’s religions. Nearly five decades later, he sits in a sunny window in the living room of his home in Berkeley, California. He’s still married to Kendra, but he’s an old man now. He has trouble hearing, and with the help of a walker he can barely make it from his study to his living-room chair. But when he tells the story of that New Year’s Day in Timothy Leary’s living room, his eyes widen and he seems to lose ten years.

“What a way to start the sixties,” he says, laughing.

Seeker: Newton, Massachusetts, February 1961

Richard Alpert would have taken the magic mushrooms in Mexico with the rest of the gang, back in the summer of 1960, but he arrived a few days after Leary’s first trip. Everyone was still aglow in the aftermath of the experience, but the mushrooms were gone. Richard would have to wait nearly nine months before he got his own psychedelic baptism back home in Timothy Leary’s living room. Back in Mexico in the summer of 1960, Leary was still feeling the mystic wonder of it all when he met Alpert at the Mexico City airport. Richard had quite an adventure just getting there. He’d just bought his fl ying teacher’s Cessna and had decided to fly from San Francisco to Mexico City — over the startled objections of his instructor.

“There’s no way you can do that,” his teacher warned. “That’s a really difficult airport to fly into. Traffic control is a mess down there.”

“Don’t worry,” Alpert said. “I’ll be fine.”

He bought the plane on a Saturday and flew down on Sunday. He had not told his flight teacher he was going to fly down tomorrow. If he had he probably wouldn’t have gotten the keys. Alpert had already rounded up a Stanford anthropologist who needed a lift to Mexico, but he didn’t tell him he had just bought the Cessna the day before. Mexico City is at a high elevation, making it a difficult place to land. His passenger sat next to Alpert with a terrified look on his face as Richard dodged other airplanes on his approach.

“Don’t worry,” Alpert said. “We’ll be fine.”

They arrived and found Leary waiting in the terminal. Richard was eager to tell Tim about the terrors of his airplane trip, but it turned out Leary had an even more amazing trip to talk about.

They stood in the lobby as Alpert told the story about buying the plane and flying down to Mexico the next day.

“That’s quite a trip, Richard,” Leary said. “You know, I’ve been doing some flying myself — internally.”

They got to the villa, and all the guests were sitting around the pool talking up the mushrooms. But the magic fungi were gone, and no one knew how to find Crazy Juana and score some more. Meanwhile, Leary was already planning his mushroom research project and wanted to begin as soon as he got back to Harvard. He and Alpert were trained clinicians, but this was not going to be like other drug tests. They were going to change the world.

“We’re going to take a whole new approach with this research,” Leary told Alpert. “Everyone thinks these drugs cause psychosis, but that’s because they’ve been controlled by psychiatrists. Of course they’re going to view this as psychosis. That’s all they know. But there is really something deeper going on here, Richard. Wait until you try them. I learned more about psychology from these mushrooms than I did in graduate school. These drugs can revolutionize the way we conceptualize ourselves — not to mention the rest of the world. It’ll be great. We’ll give them to philosophers, poets, and musicians.”

Alpert had been working with Leary for about a year at Harvard. Richard might have had the bigger office at the Department of Social Relations, but Tim was clearly the mentor in their relationship. There were about ten research psychologists in the department, all of them interested in the dynamics of the human personality. As he got to know Leary, Alpert started changing the way he looked at Harvard, and the way he looked at himself. Until Tim showed up, Richard was happily playing the professor role. He’d go to faculty meetings, sit in big chairs, and have tea from a silver tea service. It was easy to let the whole experience go to your head. Alpert would walk through Harvard Yard and begin to think he really was somebody. He was a member of the Harvard faculty. But Tim wasn’t like that. He was the first guy Alpert ever met who was not impressed by Harvard. It was just a job.

Their relationship went beyond the office — even before they made the psychedelic bond. Tim arrived at Harvard with two children and no wife. Richard started hanging out with the kids, Susan and Jack, and began taking care of them. They started calling him “Uncle Dick,” and he started acting out the role of surrogate mother. Richard was a bachelor. Tim was a bachelor with kids. Sometimes they’d find another baby sitter and go out drinking in Harvard Square. Lots of drinking, as in that 1950s kind of drinking.

Alpert had missed out on the mushrooms in Mexico and wasn’t in Cambridge in the fall of 1960, when Leary started gathering together the tribe that would become the Harvard Psilocybin Project. Alpert had been teaching that semester as a visiting scholar at the University of California at Berkeley, but he was getting lots of fascinating reports about what was happening back at Harvard. He couldn’t wait to get back and join the party, and his chance finally came one day in February 1961.

Alpert returned just as the biggest storm of the season dumped two feet of snow on the streets of Newton. Leary invited him over to his house for a Saturday-night initiation. By now, Leary and his growing band of graduate students had started experimenting with a new batch of drugs they’d gotten from Sandoz Laboratories in Switzerland. The drug was a synthesized form of psilocybin, the active ingredient in the magic mushrooms of Mexico. The psychic effects were the same, but the dose was easier to control.

While Alpert had been in California, Leary had begun to assemble an eclectic squadron of test pilots at his increasingly chaotic home. They included Beat poet Allen Ginsberg; jazz trumpeter Maynard Ferguson; William Burroughs, the legendary novelist and heroin addict; and Alan Watts, the popular Buddhist writer and commentator. Ginsberg was sitting at Leary’s kitchen table the day Alpert burst in from the cold. Alpert joined them at the table, upon which stood a bottle of pink pills from Sandoz labs. He measured out ten milligrams of the drug and washed the pills down with a few gulps of beer.

Allen and Tim and Richard sat down in the kitchen and waited. Right away there was a bit of a melodrama. Tim’s son, Jack, was upstairs when the boy’s dog ran out of the house. The dog had been out galloping around in deep snow and came in panting heavily. They all started thinking, “Oh, no! The dog is dying!” Then they figured out that they really couldn’t tell if the dog was dying because they were so high. Their thinking and senses were too distorted. Jack was eleven years old. He was upstairs watching television and a bit peeved that these silly adults were bothering him. He came down, assured them that the dog was fine, then marched back upstairs to the TV.

Alpert started really coming onto the psilocybin. There was too much talking in the kitchen, so he walked into the living room, a darker and more peaceful setting. He sat down on the sofa and tried to collect himself. Looking up, he saw some people over in the corner. Who were they? Were they real? Then he started to see them as images of himself in his various roles. They were hallucinations, but they seemed so real. There was the professor with a cap and gown. There was a pilot with a pilot’s hat. There was the lover. At first, he was a bit amused by the vision. Those are just my roles. That role can go. That role can go. I’ve had it with that role. Then he saw himself as his father’s son. The feeling changed. Wait a minute. This drug is giving me amnesia! I’ll wake up and I won’t know who I am! That was terrifying, but Alpert reminded himself that those roles weren’t really important. Stop worrying. It’s fine. At least I have a body. Then Alpert looked down on the couch at his body. There’s no body! Where’s my body? There’s no-body. There’s nobody. That was terrifying. He started to call out for Tim. Wait a minute. How can I call out to Tim? Who was going to call for Tim? The minder of the store, me, would be calling for Tim. But who is me? It was terrifying at first, but all of a sudden Alpert started watching the whole show with a kind of calm compassion.

At that moment, Richard Alpert met his own soul, his true soul. He jumped off the couch, ran out the door, and rolled down a snow-covered hill behind Leary’s house. It was bliss. Pure bliss. At the time, Alpert’s parents were also living in Newton. Their home was just five blocks from Leary’s house on Homer Street. It was three in the morning, but that didn’t stop a stoned Richard Alpert from storming through the snow to go see his parents. When he got to his parents’ house, he saw that no one had shoveled the deep snow off their walkway. So he went into the garage and got the shovel. In his drugged state, he saw himself as a young buck coming to the rescue. He was all- powerful. He would save his parents! It all seemed so mythological. Then he looked up at the window and saw his parents standing there. They were obviously peeved, or at least confused. Then they assumed that their son must have been drinking with Leary. Alpert saw them up in the window and waved at his startled parents. Then he stuck the shovel in the snow and started dancing around it. He felt so fine, perfectly fine.

Alpert recounts this tale of snowy bliss just a few days shy of the forty-seventh anniversary of the event, yet he remembers it like it was last night. As he tells the tale he’s sitting beside a large picture window overlooking the rugged coast on the island of Maui. He says he’s come here to Hawaii to die. But when he tells the story of that wondrous winter night his eyes light up like those of an excited little boy. He was twenty-nine years old then. He’s seventy-six years old now. Leary is dead. Ginsberg is dead. Alpert is no longer a young buck. A nearly fatal stroke a decade earlier has left him paralyzed on his left side and confined to a wheelchair. The stroke nearly destroyed his ability to find words and speak them. He struggles mightily to tell the story, once again, of the events that changed his life.

“Until that moment I was always trying to be the good boy, looking at myself through other people’s eyes,” he says. “What did the mothers, fathers, teachers, colleagues want me to be? That night, for the first time, I felt good inside. It was OK to be me.”

Copyright © 2010 by Don Lattin. Used with permission of HarperOne, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.

Don Lattin is the author of Jesus Freaks: A True Story of Murder and Madness on the Evangelical Edge. His work has appeared in dozens of magazines and newspapers, including the San Francisco Chronicle, where he covered the religion beat for nearly two decades. Lattin has also appeared on Dateline, Good Morning America, Nightline, Anderson Cooper 360, and PBS’s Religion and Ethics Newsweekly.

Teaser image by Ryuugakusei, courtesy of Creative Commons license.