Nobel Prize winner Jose Saramago died

last Friday. In addition to being a non-repentant communist, he was a dedicated

supporter of the indigenous Mayan communities in rebellion in Chiapas, Mexico.

He travelled to Mexico and Chiapas on several occasions and met with the

insurgent women and men there. Once, while in Mexico City he gave a speech in

which he said, "when I come to Mexico I am not a communist, I am a

Zapatista." In the mid-1990s I had the privilege to meet with Saramago in

New York City with Juana Ponce de Leon, Dan Simon and others to discuss his

work and invite him to write the foreword to a book Juana and I were working on

together for Seven Stories Press — Our Word is Our Weapon: The Selected

Writings of Subcomandante Marcos.

Saramago agreed to write the essay, which is posted below.

During our

meeting with Saramago in New York, the issue of the "real" identity

of Subcomandante Marcos came up. At first, Saramago thought we should cite

Subcomandante Marcos's "real name." Juana and I took issue, and countered

that the name Saramago proposed we use for Marcos was the name that the Mexican

government had used in their propaganda campaign to neutralize the Zapatistas.

The rebel communities call him Subcomandante Marcos, and is the name he uses to

sign his writings. The great maestro paused a moment, touched his glasses and

in response told us the following story….

"During a high point in the

Mexican government's campaign against the Zapatistas, the Zedillo

administration circulated a press release claiming to reveal the real identity

of Subcomandate Marcos was Rafael Sebastian Guillen Vicente. As part of the

campaign, then Mexican President Ernesto Zedillo said 'I'll meet with Rafael

Gullien any time , anywhere.' A few days later Subcomandante Marcos responded

to Zedillo's taunt by saying, 'Excellent. Then the three of us can all meet

together.'"

— Greg Ruggiero,

Editor, City Lights Books Open Media Series

* * *

The following is excerpted from Zapatista by Jose Saramago, translated from the Portuguese by Gregory Rabassa, Foreword to Our Word is Our Weapon: Selected Writings of

Subcomandante Insurgente Marcos, edited by Juana Ponce De Leon. Published by Seven Stories Press.

In 1721, with a feigned innocence

that couldn't conceal his tart sarcasm, Charles-Louis de Secondat asked: "Persians? But how is it possible for someone to

be Persian?" It's been almost

three hundred years now since the Baron de Montesquieu wrote his famous Lettres

Persanes and even today we haven't succeeded in putting together an intelligent

answer to this most essential of all questions found on the historical agenda

of human relationships. As a

matter of fact, we still can't understand how it was ever possible for someone

to have been a "Persian," and furthermore, as if such a peculiarity

were not out of the question, to persist in being one today when the picture

the world lays before us seeks to convince us that the only desirable and

profitable thing to be is what in very broad and artificially conciliatory

terms is customarily called "Western" (Western in mentality,

fashions, tastes, habits, interests, manias, ideas…), or, in the all too

frequent case of not suc ceeding in reaching such sublime heights, to be

"Westernized" in some bastard way at least, whether the results were

attained through force of persuasion or in a more radical way, if there was no

other solution through persuasion by force.

To be "Persian" is to be someone strange, someone different,

in simple terms to be the "other." The very existence of the

"Persian" has been enough to disturb, confuse, disrupt, and perturb

the workings of institutions; the "Persian" can even reach the

inadmissible extreme of upsetting what all governments in the world are most

jealous of: the sovereign

tranquility of their power.

The indigenous were and still are "Persians" in Brazil (where

the landless now represent another type of "Persians"). The indigenous in the United States

once were but have almost ceased to be "Persians." In their time

Incas, Mayas, and Aztecs were "Persians" and their descendants were

and still are "Persians," wherever they have lived and still live.

There are "Persians" in

Guatemala, Bolivia, Colombia, and Peru.

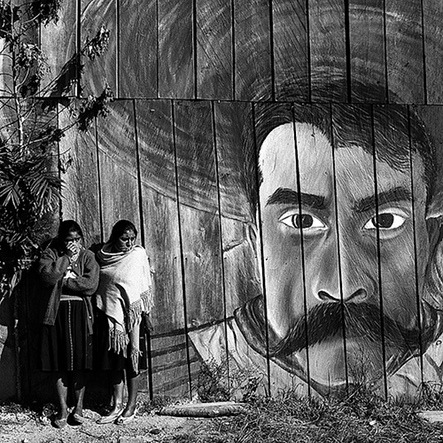

There is also an overabundance of "Persians" in that painful

land of Mexico, where Sebastiao Salgado's inquiring, rigorous camera drew

shudders from us with the challenging figures facing us. They ask: How can it be that you

"Westerners" and "Westernized" people to the north, south,

east, and west, so cultured, so civilized, so perfect, lack that modicum of

intelligence and sensibility necessary to understand us, the

"Persians" of Chiapas?

It is really only a matter of understanding, understanding the

expression in those looks, the solemnity of those faces, the simple way of

their grouping together, feeling and thinking together, weeping the same tears

in common, smiling the same smile, understanding the hands of the sole survivor

of a slaughter that are held like protective wings over the heads of her

daughter, understanding this

endless stream of living and dead, this lost blood, this acquired hope, this

silence of someone who has borne centuries of demanding respect and justice,

this suppressed anger of someone who has finally wearied of hoping.

Six years ago, changes were

introduced in the Mexican Constitution in obedience to the neo-liberal

"economic revolution" directed from without, and were mercilessly

applied by the government to bring agrarian reform and redistribution to an

end. This reduced to nothing the possibility for landless peasants to have a

parcel of land to cultivate. The indigenous thought they could defend their

historic rights (or simply their common-law ones, in case it was assumed that

indigenous communities had no place in the history of Mexico… ), by

organizing into civic societies which were characterized, and still are, in the

singular matter of renouncing any kind of violence, starting with the one that

was their due.

These

societies had the support of the Catholic Church from the beginning, but that

protection was of little use to them.

Their leaders and representatives kept being jailed, the systematic,

implacable, and brutal persecution by the powers of the State and the large

landowners increased in conjunction with and under the shadow of the interests

and privileges of both. They

continued the violent acts of expulsion from the indigenous' ancestral lands,

and the mountains and jungle, many times over, became the last refuge of the

people displaced. There in the

dense mists of the heights and the valleys the seeds of rebellion would

germinate.

The indigenous of Chiapas aren't the only humiliated and offended people

in this world. In all places and

at all times, regardless of race,

color, customs, culture, religious belief, the human creature we are so proud

to be has always known how to humiliate and offend those whom, with sad irony,

he continues to call his fellows.

We have invented things that don't exist in nature: cruelty, torture,

and disdain. By a perverse use of

race, we've come to divide humanity into irreducible categories: rich and poor, master and slave,

powerful and weak, wise and ignorant. And incessantly in each of these

divisions we've made subdivisions so as to vary and freely multiply reasons for

disdain, humiliation, and offense.

In recent years Chiapas has been the place where

the most disdained, most humiliated, and most offended people of Mexico were

able to recover intact a dignity and an honor that had never been completely

lost, a place where the heavy tombstone of an oppression that has gone on for

centuries has been shattered to allow the passage of a procession of new and

different living people ahead of an endless procession of murders. These men, women, and children of the

present are only demanding respect for their rights, not just as human beings

and as part of this humanity, but also as the indigenous who want to continue

being indigenous. They've risen up

most especially with a moral strength that only honor and dignity themselves

are capable of bringing to birth and nursing in the spirit even while the body

suffers from hunger and the usual miseries.

On the other side of the heights of Chiapas lie

not only the government of Mexico but the whole world. No matter how much of an attempt has

been made to reduce the question of Chiapas to merely a local conflict, whose

solution should be found within the strict confines of an application of

national law-hypocritically malleable and adjustable, as has been seen once

again, according to the strategies and tactics of economic and political power

to which they are surrogate-what is being played out in the Chiapas mountains

and the Lacondona Jungle reaches beyond the borders of Mexico to the heart of

that portion of humanity that has not renounced and never will renounce dreams

and hopes, the simple imperative of equal justice for all.

As that figure, exceptional and

exemplary for many reasons, whom we know by the name of the Subcomandante

Insurgente Marcos has written, "a world where there is room for many

worlds, a world that can be one and diverse," a world, I might add myself,

that for all people and all time declares untouchable the right of everyone to

be a "Persian" any time he or she wants to and without obeying

anything but one's own roots…

The mountainous highlands of Chiapas are without a doubt one of the most

amazing landscapes my eyes have ever seen, but they are also a place where

violence and protected crime hold forth.

Thousands of indigenous, driven from their homes and

their lands for the "unpardonable crime" of being silent or open

sympathizers with the Zapatista Front of National Liberation, are crammed into

camps of improvised huts, where there is a lack of food, where the little water

available is almost always contaminated, where illnesses like tuberculosis,

cholera, measles, tetanus, pneumonia, typhus, and malaria are decimating adults

and children. All this is hppening in full view of the indifferent authorities

and official medicine.

Some sixty thousand soldiers-no more nor less than a third of the

permanent strength of the Mexican army at present-occupy the State of Chiapas

under the pretext of defending and assuring public order.

The factual reality, however,

gives the lie to this justification. The Mexican army is protecting one part of

the indigenous population; it is not only protecting it but at the same time is

teaching, training, and arming these indigenous who are generally dependent

upon and subordinate to the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI), which for

sixty years has been exercising uninterrupted and practically absolute power.

These indigenous are-not by any extraordinary coincidence-the ones who make up

the various paramilitary groups organized with the sole objective of

undertaking the dirtiest work of suppression: the attack, rape, and murder of

their own brothers and sisters.

Acteal was one more episode in the terrible tragedy that begun in 1492

with invasion and conquest. All

through the five hundred years the indigenous of Ibero-America (and I use this

term intentionally so as not to let escape judgment of the Portuguese and later

on the Brazilians, who continued the genocidal process that reduced the three

or four million Indians existent in Brazil during the period of discovery to

little more than 200,000 in 1980) were passed, in a manner of speaking, from

hand to hand. They were handed from the soldier who killed them to the master

who exploited them, while in between there was the hand of the Catholic Church,

which made them exchange one set of gods for another, but which in the end was

unsuccessful in changing their spirit.

After the butchery of Acteal there began to be

heard over the radio words that said "We're winning." Some unaware

person might have thought that it was a matter of an insolent and provocative

proclamation by murderers. He

would have been mistaken. Those

words were a message of hope, words of courage which like an embrace over the

airwaves united the indigenous communities. While they wept for their dead-another forty-five added to a

list five-centuries old-the communities stoically lifted their heads and said

to each other "We're winning," because it really could only have been

a victory, and a great one, the greatest of all, being capable of surviving

humiliation, offense, disdain, cruelty, and torture in that way. This was a

victory of the spirit.

Eduardo Galeano, the great Uruguayan writer, tells how Marcos went to Chiapas and spoke to the

indigenous, but they didn't understand him. "Then he penetrated the mist, learned to listen, and

was able to speak." That same mist which prevents one person from seeing

is also the window that opens onto the world of the other, the world of the

indigenous, the world of the "Persian"… Let us look in silence, let us learn to listen, perhaps

later we'll finally be able to understand.

* * *

A video interview with Jose Saramago, shot by Michael Eisenmenger, may be seen here.

Mr. Saramago was known almost as much for his unfaltering Communism as

for his fiction. In later years he used his stature as a Nobel laureate to

deliver lectures at international congresses around the world, accompanied by

his wife, the Spanish journalist Pilar del Río. He described globalization as

the new totalitarianism and lamented contemporary democracy's failure to stem

the increasing powers of multinational corporations. To many Americans, Mr. Saramago's name is associated

with a statement he made while touring the West Bank in 2002, when he compared

Israel's treatment of Palestinians to the Holocaust. As a professional novelist, Mr. Saramago was a late

bloomer. A first novel, published when he was 23, was followed by 30 years of

silence. He became a full-time writer only in his late 50s, after working

variously as a garage mechanic, a welfare agency bureaucrat, a printing

production manager, a proofreader, a translator and a newspaper columnist. In 1975, a countercoup overthrew

Portugal's Communist-led revolution of the previous year, and Mr. Saramago was

fired as deputy editor of the Lisbon newspaper Diário de Noticias. Overnight,

along with other prominent leftists, he became virtually unemployable. "Being fired was the best luck of

my life," he said in an interview in The New York Times Magazine in 2007. "It

made me stop and reflect. It was the birth of my life as a writer." — Excerpt

from the New York Times obituary.

Image by mexadrian, courtesy of Creative Commons license.