"They believe that all dreams which they have are real. . . but to tell the truth in the matter, these are visions of the devil, who deceives and misleads them."

– Samuel de Champlain, Voyages (1603)

"I have data upon data of new lands that are not far away."

-Charles Fort, New Lands (1923)

[Daemonic Dispatches] • Every time I take a ferry across Lake Champlain, I find myself thinking about two earlier voyagers on these waters – Samuel de Champlain and Charles Fort.

On July 29th, 1609, as Champlain made his way south upon the lake that the Abenaki on the west knew as bitawbagw – "the waters between" – the explorer, navigator, colonizer, and "Father of New France," he had much on his mind. For the night before he woke from a nightmare in which he saw Iroquois warriors drowning in the lake. Each morning on the journey south from Quebec, his Montagnais and Algonquin guides pestered him, eager to learn what he might have dreamed, especially about their dreaded cannibal enemy, the Magua. Champlain dismissed their questions as illustrative of their "low, animal" beliefs. But that very afternoon they met an Iroquois war party, and the historic battle – in which Champlain felled two Mohawk chiefs with his own arquebus – would seal the fateful alliance of the French with the Algonquians, and the Iroquois with France’s nemesis – Great Britain.

Almost three centuries later, the teenage Charles Fort, with a half dozen friends, rode the train north from Albany along Lake Champlain, looking for a suitable spot for a camping adventure. Sighting an island not far off the western shore, they got off at the next stop, walked to the lakeshore, "borrowed" (à la Huck Finn) a rowboat, and colonized the island, which, much to their dismay, was already home to a well-equipped summer camp and shotgun-toting duck hunters.

While on the island, the boys never sighted Lake Champlain’s monster, "Champ," nor heard the cry of the loup garou (the Valley’s French-Canadian inhabitants' term for the werewolf), nor saw a giant black Thunderbird (reported in the 1980s from near the lake’s eastern shore) darken the skies, but all these and so many more daemonic manifestations would later become as much Fort's stock-in-trade as uncharted islands, rivers, lakes, peninsulas and peoples were Champlain's. The boy explorer/conqueror grew up to be the twentieth century’s premier cataloguer, chronicler, and interpreter of anomalous phenomena — indeed, we now call such phenomena “Fortean.” Though writer Colin Wilson called Fort “a kind of patron saint of cranks,” it would not be too much to say that long before Thomas Kuhn’s The Structure of Scientific Revolutions (1962), Fort offered in his madcap tour de forces (Book of the Damned; Wild Talents; Lo!; New Lands) a devastating critique of contemporary natural science, particularly astronomy. Fortean Times, the British magazine founded in the 1970s to continue Fort’s work, continues to feature articles on the unexplained.

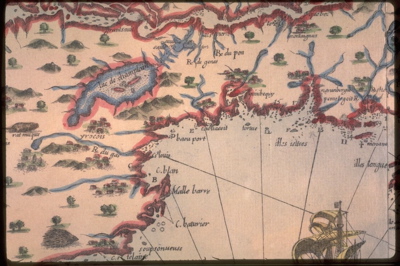

King Henry VI befriended (and later outfitted) Champlain because he was keen to know more about the vast northern lands to which he held title, and Champlain had on a two-year voyage to the West Indies shown his talents as observer and navigator of unfamiliar waters and lands. His maps and drawings of the newly "discovered" lands are a testament to his empirical acumen; but his condemnation of the Montagnais' astral acumen – their skillful navigation around the shoals and reefs of the dream world – marks him as a poor man to send into the crow’s nest. He remained completely obliviousness to his own episode of clairvoyance – his precognitive vision of the seminal battle with the Mohawk.

The Age of Exploration boasts dozens of Champlains, intrepid mappers of the physical world then coming under European domination. The world now needs as courageous a crew to map the infraphysical, the supersensible, the world that Champlain's educated contemporaries still might have termed the "daemonic," that is, "pertaining to the gods."

Charles Fort was the twentieth century’s premier cartographer of these mysterious terrains, since he no more respected the scientific gatekeepers than he did the "Keep Out!" signs on that little Lake Champlain island. The most confounding of beings – sea serpents, rains of frogs, fireballs, airships, poltergeists – reached his desk as data, as events demanding deep contemplation, not easy dismissal.

In the spirit of both Champlain and Fort, my "Daemonic Dispatches" will aim to describe with the cartographer’s discerning eye and interpret with the mythographer’s spirited clairvoyance the new daemonic lands breaking in upon human consciousness. . .