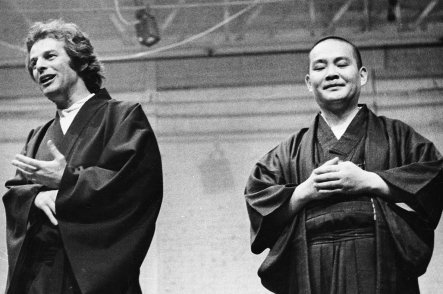

In 1970, John Lennon introduced to the world Alejandro Jodorowsky and his movie El Topo, which the filmmaker wrote, starred in, and directed. The movie and its author instantly became a counterculture icon. His spiritual quest began with the Japanese master Ejo Takata, the man who introduced him to the practice of meditation, Zen Buddhism, and the wisdom of the koans. At the direction of Takata, Jodorowsky became a student of the surrealist painter Leonora Carrington, thus beginning a journey in which vital spiritual lessons were transmitted to him by various women who were masters of their particular crafts.

This article is excerpted from The Spiritual Journey of Alejandro Jodorowsky, recenty published by Inner Traditions.

“Ejo, I want to propose something. Let us bury this stick among the trees here, as if it were a plant. Let us imagine that someday it will sprout and produce branches, even fruit . . .”

After we finished burying it, my friend gave a huge sigh. It was as if he had shed an immense burden. He burst out laughing, then he took his monk’s robe out of the net sack. “It was my master, Momon Yamanda, who gave me this kesa.* He wove into it parts of the funeral shrouds of his father and his mother. Do you understand? We often speak of the transmission of the light, but the real master transmits the shrouds of the dead. We must see life — both our own and that of the cosmos — as an agony. This is the teaching of the Buddha Shakyamuni. After his satori, he went to the place where they incinerate corpses, and he gathered pieces of cloth left there, washed them, dyed them, and sewed them together painstakingly and slowly, giving his total attention to every stitch. That kesa was transmitted from patriarch to patriarch through the ages. Everyone who wore it while meditating was burning in body and in soul. To reach the marrow of the soul, everything superfluous must be burned to ashes. By wearing the garments of so many dead people, Buddha taught that liberation is to be obtained for them as well. When a flower opens, it is springtime for the whole land. The Buddha is like the brilliant prow of a vessel that leads it and its blind passengers to the port of salvation. I know that my way is not the same as yours, for you are more attracted to artistic creation than to meditation. But you know — there is really no difference between us. Compassion inhabits us both. Just this once, please give me the pleasure of seeing you dressed in my kesa.”

It was still so early in the morning that we were alone in the woods. I undressed slowly. Sensing an abyss before me and another behind me, I inhaled every breath of air deeply and exhaled each time as if it were my last breath. Then, feeling like a fugitive so weary of fleeing that he finally surrenders to his pursuers, I entered into the folds of the robe. Although its color was a uniform ochre, that of dry earth, it was composed of many pieces of cloth of different sizes, each connected to others with large stitches that dissolved into the form of the garment. It clung to my skin readily. I absorbed the years of meditation of Ejo, his master, and those of other masters and patriarchs all the way back to Shakyamuni Buddha himself. The sensation of my body changed, and I finally understood what it was to feel like a mountain. There was no more space or time. The voice of the first awakener resounded unceasingly: “Never pretend anything that is not certain. There is no substantial ego, no object that is not impermanent. Perceptions, feelings, and visions are processes empty of real substance. Life is suffering. Birth, illness, old age, and death are suffering. To be separated from those we love is suffering. To be forced to be with those we do not love is suffering. To be unable to satisfy our desires is suffering.”

Yet Ejo’s kesa seemed to be saying to me: “Do not dwell at the surface of things. Beyond the Buddha’s words, in the deepest depths, in the highest heights, lives an exalted passion. Listen to cosmic consciousness, the phoenix surging forth from the mind in flames, for it is telling you: Life is pure happiness. Birth, illness, old age, and death are four gifts as marvelous as the cycle of the four seasons. You can never be separated from those you love, for they live in you forever. You cannot be forced to be with those you do not love, for you have let go of aversion. Your light, like that of the sun, is for everyone, and you love even those who appear odious. To be unable to satisfy your desires is not suffering-the important thing is the prodigious gift of desire itself, satisfied or not, which gives you your sense of being alive.

“Go beyond this litany of The cause of suffering is attachment to desires and things, because when attachment to desires and things is free from all possessiveness, it is sublime goodness. All that appears to be impermanent is engraved in the memory of God. Every second is eternity.

“Go beyond the litany of Put an end to all attachments and end all suffering. No-we cannot end these attachments. If all is one, then how can one detach itself from itself? Attachment through love is the way of realization. Eternal being is attached to you with an infinite tenderness.

“Go beyond even the litany of the Buddha’s Eightfold Path of ending suffering by right seeing, right thinking, right speech, right action, right livelihood, right effort, right attention, and right concentration. Free yourself from all conceptual chains; trust in the wisdom of Creation. You are not merely a part of Creation, you are Creation. To live in full happiness, walk in the infinite, pathless land. Let your eyes see what they invite you to see; do not put blinders on them. Let your thought wander in all dimensions, let your every word be rooted in your heart, act like a beloved child of beloved parents, see a thousand lives in one life. Make no effort; instead, allow things to happen through you, for every natural act is a gift. Right attention and right concentration are the offspring of a passionate love. Think, feel, desire, and live with pleasure. A cat makes no effort to concentrate when it sees a mouse.

“Go beyond the litany of Everything arises from ignorance. Why must we be born? Why must we die? Unity is total knowledge. When you become one with it, there is no ignorance. When the sun appears, darkness dissipates. We must die in order to be born. Existence venerates death; it does not deny it. There is no will to exist, for we already exist eternally. Anxiety to live is born of a lack of generous contact with the world, which is neither inner or outer, because there is no separation. To look is to bless; to hear, touch, feel, taste is to bless. The body, soul, spirit, and mental functions are one and the same. Ignorance is the desire to separate ourselves from them.

“Go beyond the litany of Everything changes ceaselessly. Everything passes. Everything is impermanent. Nothing is permanent. In God, nothing changes ceaselessly. Everything is permanent, eternal, infinite. Nothing passes away.

“Go beyond the litany of All is emptiness, ku, zero point. Nothing is ku; emptiness is an illusion. All is filled with God.”

At one crucial moment, as the rough cloth adhered to me, pressing upon me as if glued to my skin and bones, immobilizing me in a centuries-old posture while my thoughts flooded like a torrent in all directions, transforming legends, presuppositions, and written ideals into a mummified skin, Ejo Takata spoke to me in a voice full of kindness: “You are constructing everything that you think around the word God. If I took this word away from you, you’d have nothing left. Tell me: What is God for you?”

The first thing that came to mind was the definition that had fascinated poets and philosophers through the ages, from Hermes Trismegistus all the way to Jorge Luis Borges, including Parmenides, Alain de Lille, Meister Eckhart, Giordano Bruno, Copernicus, Rabelais, Pascal, and so many others. So I replied: “God is an infinite sphere whose center is everywhere and whose circumference is nowhere.”

Then, to head off any possible critique from Ejo about my intellect needing to die, I shouted: “Kwatzu!”

But then I had to confess, in a grumbling voice, that this definition was unacceptable even to me, because as soon as it was formulated in my mind, it became just one more prison. There are thinkers who are seduced by the sublime, geometric beauty of it, the sphere being the most perfect of all forms for them, but for a lover of organic beauty, a tree, a leaf, or an insect could be a better incarnation of perfection. Defining God as an infinite sphere is as absurd as defining God as an infinite fly. In any case, the infinite is beyond form by its very nature. Besides, because the center is everywhere and the circumference nowhere, there can be no parts. If all is center, what does center mean? A center requires something other than itself. It is absurd to speak of a center while affirming that this center is the only thing that exists. It is the same as saying: “God is an infinite human whose navel is everywhere and whose skin is nowhere.”

This provoked Ejo to a fit of uproarious laughter. Then he became serious again. “You still haven’t answered my question. All you’ve done is quote someone else’s definition, and then criticize it. Consult your hara** and then reply.”

“Ejo, my reason is always seeking distinctions and limits. It can neither define nor explain nor understand a reality in which absolutely everything is united and forms one unique truth, but if we grant that no concept is reality, that it is only a limited sketch, I can learn to use words not as definitions of the world, but as symbols of it. A symbol allows for a vast number of meanings, as many as there are individuals to perceive it.

“For me, the ‘personal’ God, the prime actor of every sacred work, cannot have a geometrical, mineral, animal, vegetable, human sexual, racial, or other form. He cannot even have a name and cannot be the special property of any religion. Any quality or category that I might give him would amount to only a superstitious approximation. He is impossible to define with words or images and inaccessible to search for. It is absurd to say anything about God. The only possibility that remains: to receive him. But how? How can I receive what is inconceivable, ungraspable? I can do so only through the changes and mutations that it works in my life in the form of clarity of mind, happy love, creative capacity, and a joy in living that remains in spite of the worst suffering. If I imagine God as eternal, infinite, and omnipotent, it is only by contrast with what I believe myself to be: finite, ephemeral, and impotent in the face of the transformation known as death. Yet if everything is God and God does not die, then nothing dies. If everything is God and God is infinite, then nothing has limits. If everything is God and God is eternal, then nothing has a beginning or end. If everything is God and God is omnipotent, then nothing is impossible. Though I cannot name that or believe in that, I can still intuitively sense it in my deepest being. I can accept its will, a will that creates the universe and its laws. And I can imagine it as allied to me, whatever happens.

“It’s true that I need not say all this. Words are not the direct way-they point, but they do not go there. I accept that I belong to this unfathomable mystery, an entity without being, nonbeing, or dimension. I accept to surrender to its designs, to trust that my existence is neither an accident nor an illusion nor a cruel game, but an inexplicable necessity of its work. I know that this permanent impermanence is part of what my mind calls the cosmic plan. I believe that even if I am an infinitesimal cog in an infinite machine, I participate in its perfection, and that this destruction of my body is the portal I must cross to submerge myself in what my heart feels as total love, what my sexual center feels as infinite orgasm, what my intellect calls radiant emptiness, and what my body considers its mysterious home. If we are one with the universe, then it is our temple. We are renters beholden to a landlord who feeds us and supports and sustains us in life for the lot of time according to his will. This house is our certain refuge, but we can make it into either a Garden of Eden or a garbage dump. It can be a place of flourishing creativity or a dark, stinking realm where bad taste reigns. Between these impenetrable walls we can either thrive or commit suicide. The house of God does not behave in a certain way-it is simply there. Its quality depends on the use we make of it.”

Ejo Takata smiled. Mimicking my last phrase and way of talking, he said: “The mind does not behave in a certain way-it is simply there. Its quality depends on the use we make of it.

“I would like to remind you of a koan from the secret book. The disciple Hokoji*** was agitated and came to ask his master Baso: ‘What transcends existence?’ Baso answered: ‘I will tell you when you have drunk the entire Western River in a single gulp.’ Hokoji suddenly became calm, bowed respectfully, took a cup of tea, and drank it down in a single gulp.”

“I know, I know, Ejo. It is impossible to give a true reply to such questions. How can we define the indefinable, describe the indescribable, or think the unthinkable? Instead of giving a solution, Baso demanded the impossible of his student: to swallow a river. Hokoji realized that there is nothing beyond existence. By drinking a gulp of tea, he sided with the natural against the metaphysical. Yes, I know, but I am not a monk. I am a poet. And the poet’s ideal — even though he knows the project is doomed to failure — is to express the eternal silence in words.”

“Alejandro, neither of us is a monk or a poet. We are beings beyond definitions. When I asked you to define God, I was hoping that instead of elaborating on your ‘artistic’ theories, you would say something like: ‘I will tell you when you drink an entire river and eat a herd of elephants, bones and all.’ Now, how about leaving here and having a nice cup of tea or some tacos?”

I had the sensation of lightning striking my tongue, and I felt like biting it off. Of course I understood that words such as God, spirit, and infinite circle are interchangeable, but I was still enraged. I felt an immense rage that had been accumulating for years. By what right could this Japanese make fun of me when he himself was caught like a fly in the web of Buddhism? I began to spit out words in anger. I knew that much of what I was saying was foolish, but I could not restrain myself, because I still had an arrogant desire to shake that granite self-assurance I had always perceived in him.

“Ejo, you are fond of repeating that maxim of ‘If you meet the Buddha on the road, cut off his head.’ Yet you yourself continue to meditate in the same position as the first patriarchs. You have continued to wear your kesa, which imitates the Buddha’s renunciation of the world, and you repeat like a parrot or a fanatic the sutras of his words. You fill your days with useless ceremonies that you learned as a child. You live in a past that is not even your own. Among millions of poor Indians, Shakyamuni was the son of royalty and wealth. His father, the king, gave him everything: a palace surrounded by fabulous gardens, exquisite food, the most elegant dress, the most beautiful of women, hundreds of servants. Living in this luxurious prison, he did not know the misery of the lives of his numberless servants. Suddenly, because a small, dead bird fell upon his head, the future Buddha had a crisis like that of a hysterical woman. Reality was not what he thought it was! So he reacted as spoiled children the world over react, and instead of learning to accept life as it is, he began to hate it. ‘Life is suffering!’ he proclaimed. ‘It is a horror of old age, illness, and death! This is all a result of being born! To be free, I must reject matter, reject incarnation, never create a new body by mating with a woman, never enjoy the pleasures of the senses. Flee, flee, flee this existence!’ He was capable of leaving his entire family and exchanging his palace for the shade of a tree. He was able to deny himself. Ashamed of his earlier life of wealth and privilege, he became the poorest of the poor, wearing a robe made of funeral shrouds that he scrounged at the burning ghats. But this is still essentially the reaction of a spoiled child!

“We, on the other hand, have not been raised in the luxury of an artificial paradise; we have always known the misery and conflicts of the world. We grew up knowing that even if we had a roof over our heads, there were many others in this world who didn’t and that every time we had food to eat, there were millions of children going hungry. We were raised among egoists, old people, sick people, dying people-yet we were still able to celebrate the dawning of every new day! Would we have agreed to don the garments of corpses? Never! This kesa of yours is not for us, because we do not want to escape life! Even if we see life as an endless cycle of reincarnation, why should we want to free ourselves from this sacred cycle? We shall return again and again. Little by little, we will make the world a bit better, we will alter the cruel laws of the cosmos, because we are the consciousness, the best aspect of the Creator. We must develop this consciousness from life to life by communicating it and multiplying it. Ejo, we are here in this life with an immense responsibility: We cannot cease to exist as long as we have not perfected this universe, as long as beings still kill and destroy each other. We must return again and again until everything is joy and the love of light is in perfect harmony with the love of darkness . . .”

At this point, I broke into tears and had to stop speaking. Ejo held me gently in his arms until my sobbing ceased. Delicately, he helped me out of the robe. He stretched out the kesa on the ground, folded it elaborately, like an origami design, as he had learned in the monastery, until it was reduced to a rectangle. Then he told me, calmly:

“My friend, it is easy for you to say that traditional sutras and teachings are lies, because they are only words. Yet these words propose experiences that can plunge us into a deeper reality. The foundational myths are necessary, because we cannot construct a society without them. It would be dangerous to try to destroy them, for such destruction would undermine the foundations on which human relationships are based and replace them with nothing. On the other hand, it is very useful to reinterpret them in a way that is in accord with what we both value. If you feel this interpretation, you will experience it.

“As for this kesa, it is now like an old, worn-out skin. Thanks to many generous hands, it has acquired its current form and served as a recipient for consciousness. It is like a caterpillar’s cocoon, and now the butterfly is ready to spread its wings. It would be stupid to continue to live in the boat that has served to help you cross the river to the other shore.

“The reason I revere the memory of Shakyamuni is because of what his figure has given the world-unlike you, I don’t bother about whether he was historically this or that or whether his deeds were mythic or real.

“Yet your poet’s point of view has shown me something that my monk’s imagination was unable to see: The patriarch gathered a bunch of funeral rags, sewed them together with care and respect, and made himself a robe. This amounts to an artistic creation, but for centuries, we have been merely imitating this creative act. Hence this kesa is not a creation of my own soul; it is ultimately an imitation of the work of Shakyamuni. It actually belongs to him, not to me. Times have changed, and we are not living in India or Tibet. Still less are we practicing the original Chinese Ch’an Buddhism. Zen must adapt itself to each country according to the customs of its people. Otherwise, it will become a form of religious imperialism. It is not Mexico that needs Japanese Zen, it is Japanese Zen that needs Mexico. The Tarahumaras weave a type of pure, simple, white linen cloth. It is a bit of luxury in their misery, symbolizing the desire for a cleaner and better life. I shall weave my own kesa with that cloth.”

Ejo arose, gathered some dry branches, and lit a fire. Upon it he placed his carefully folded old robe. With great tenderness, he watched it burn; he wore the kind of expression of loving farewell to a friend who will never return. His eyes full of tears, he turned his back and took the path that led out of the woods and back to the city.

Very soon, I returned to France without seeing him again.

———-

Footnote:

* A kesa is a cloth that is the symbol of the transmission from master to disciple. According to Taisen Deshimaru (Questions à un maître zen [Paris: Albin Michel, 1984]): “In order to sew the first kesas, they collected pieces of funeral shrouds, clothes from women giving birth, and various other ornaments . . . [T]hey used material that was considered polluted, undesirable, and destined for the rubbish heap. They washed all the pieces carefully and made them into the noblest form of vestment, a monk’s robe. Thus the most filthy garment became the purest garment, for everyone respected the monk’s kesa.”

** The hara is an energy center in the lower belly. In Zen as well as in the martial arts, it is considered to be the center of the human body. It is from this center that the shout “Kwatzu!” (or “Kiai!” in karate) originates.

*** Hokoji, or Pangyun in Chinese (740-810 CE), studied the Confucian classics and realized that mere literary study was not enough. Accompanied by his daughter, he traveled in China, seeking the greatest Ch’an masters in order to learn from them. He became the most celebrated layman in Ch’an. He was a disciple of Sekito Kisen and of Baso Doitsu, or Mazu Daoyi in Chinese (709-788 CE). The latter made a major contribution to the reform of Chinese Zen, thanks to his character and his teaching methods.