This article is taken from the author's forthcoming book, The Medium Picture: A Theory of Technological Mediation.

"Technology is a way of organizing the universe so that man doesn't have

to experience it." — Max Frisch

"We keep waiting for the robots to crush us from the sky

They sneak in through our finger-tips and bleed our fingers dry."

— Milemarker, "Frigid Forms Sell You Warmth"

We live in a realm where once clear boundaries have been reformed, pushed back, reconfigured, and often blurred beyond recognition. The age-old stable image of photography — once considered by most as a reliable visual representation of some brief slice of reality — is now suspect due to digital editing techniques. Since humans started externalizing knowledge, everything we experience is subject to mediation: by language, by technology, by marketing, by advertising.

Though Gutenberg's printing press represents what Marshall McLuhan referred to as the first assembly line — one of repeatable, linear text — and is what made large-volume printed information a personal, portable phenomenon, the advent of the telegraph brought forth the initial singularity in the evolution of information technology. As James Carey pointed out in 1988, the telegraph separated communication from transportation. As news on the wire, information could spread and travel free from its human progenitors. Information was thusly commoditized. Liberated from books and newspapers, news and ideas have since become a larger part of our economy, and indeed of our culture, than physical products.

The telegraph is so far antiquated in the landscape of communication technology, simply bringing it up in a serious manner seems almost silly. It's quite literally like using a word that has fallen out of favor. Words are metaphors, and metaphors are expressions of the unknown in terms of the known. Once a new word is known, it becomes assimilated into the larger language system. The same transition occurs in the evolution of technology: Once a device has obsolesced into a general usage, we forget its original impact. The technological "magic" dissipates.

I've been half-jokingly calling this transition the "Alf moment." When the television show Alf became popular in the mid-to-late 80s, no one wondered what was making Alf move or talk. Growing up with Jim Henson's alternate universe of Muppets had stripped the "magic" out of the medium. We were left free to enjoy the hi-jinks of this puppeted, cat-eating alien.

Mobile TV supposedly reached its "Alf moment" in 2006, but as has always been the case with communication technology, the most enthusiastic prophecies come from those with stakes in the bottom line. According to BBC News, this year's World Cup was its time. "TV is a medium that everyone understands, and so is mobile," said Dave McQueen, principal analyst at Informa Telecoms and Media, "Combining the two in the imagination of consumers is not as great a challenge as it is for other forms of mobile entertainment." Technological mediation is not inherently a bad thing, for technology holds the potential to augment our experiences as much as it does to obstruct them, but as each advance becomes "forgotten" as a part of our media lexicon, we should be mindful of what we've potentially lost.

James Howard Kunstler uses a computer systems metaphor to discuss out built environment, with the networks of the built environment as "hardware" and people's social roles within those networks as "software," but that's where his insight stops. "Computers only assisted predatory corporations in more successfully parasitizing existing value in victimized localities," he wrote. "They were most efficient at sucking the lifeblood out of complex communities" (The Long Emergency, 2006, p. 221). This latter attitude is part of the problem. Every line we draw between what's "natural" and what's "technological" gets crossed (and moved) as our world becomes more and more technologically mediated. Kunstler's line is closer to the forest where others' are closer to the fray, but neither a Heideggerian disdain for all technology (he saw no differentiation between atomic bombs and bridges) nor a gadget-headed geekiness will change the reality of the situation. We shape our tools and our tools shape us, as McLuhan put it.

Take the telephone, for example. The telephone augments communications by allowing one person to speak to another outside the constraints of place or time. It simultaneously obstructs communication by stripping it of nonverbal cues such as facial expressions and hand gestures, among other things. Upwards of sixty-five percent of face-to-face communication is nonverbal. This fact makes the telephone a leaner channel (i.e., devoid of the rich cues of face-to-face communication) than we usually assume. When we replace one channel of communication with another more-mediated channel, something is lost. This "something" of mediation is expanding exponentially, especially in the lives of our progeny.

We are literally saturated by media. Youth culture is rife with media technology. So much so that one wonders if there would be youth culture without it. Where the last generation grew up with the car, the television, and the telephone, the next generation has the personal computer, the web, and the cellular phone. If the telephone helped create adolescence, what is the cell phone creating? Advertising has grown right along side — and sometimes on — these devices. With the average child viewing more than 20,000 commercials each year, it has gone so far as to become an ontological issue. According to Adbusters editor Kalle Lasn, we've gone from "being" to "having" to "appearing to have." Our very sense of being is now mediated by our technologies.

Think I'm being melodramatic? Okay, think about how much of your time is "screen-time," that is, time spent looking at screens — TV screens, computer screens, windscreens, cell-phone screens, etc. Quite a lot, huh? How authentic can your day feel if most of it is spent staring at some screen or another?

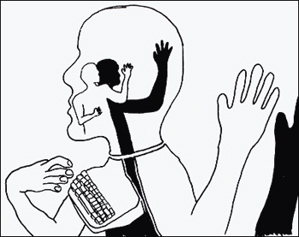

Chatter, books written, and hand-waving about the merging of humans and machines has been prevalent since the computer reared its digital head. From artificial intelligence and humanoid robots to microchip implants and uploading consciousness, the melding of biology and technology has been prophesized everywhere. Humans are indeed merging with machines, but don't believe the hype: It's not happening in the way those old science fiction books would have you think. It's been happening since we started painting on cave walls. As soon as humankind started externalizing its knowledge through the technology of language, we began blurring the lines between our tools and ourselves. The average American family now spends more every month on communication than they do on food. Technological mediation is now ubiquitous. Mediating devices infiltrate our reality through everything from our language and our clothes to our communication and transportation. We now mediate all of the spaces between ourselves and our environment, ourselves and our information, and indeed ourselves and each other.

"Technology is fairly good at controlling external reality to promote real biological fitness," writes Evolutionary Psychologist Geoffrey Miller, "but it's even better at delivering fake fitness-subjective cues of survival and reproduction without the real-world effects." Fitness-faking is the extreme effect of technological mediation, and according to Miller, it's out-pacing us: "Fitness-faking technology tends to evolve much faster than our psychological resistance to it. With the invention of the printing press, people read more and have fewer kids. (Only a few curmudgeons lament this.) With the invention of Xbox 360, people would rather play a high-resolution virtual ape in Peter Jackson's King Kong than be a perfect-resolution real human." Communication theorists call fake relationships with TV characters "parasocial relationships," and as Miller puts it, "Having real friends is so much more effort than watching Friends." Mediation isn't inherently bad, as it has the potential to augment our experiences as much as it does to obstruct them, but I think sometimes we have to take a step back — maybe even a step away — from all of these screens and things.

Do you ever find that your most emotional moments are during or after movies? Do you sometimes feel like you go through more experiences vicariously that you do directly? This is an idea that scares me more than most anything else. Here is one of my favorite passages on the subject. This is a quote from writer Nina Simons, and she says it better than I ever could:

It's important that we gather ourselves to participate more fully in the stories of our time and our lives. There's a serious threat of couch-potatoism in our culture, and we need to make a conscious effort to avoid it and to recognize the enormous energy that comes from participation. It's easy to get bogged down in the circumstantial and mundane, but if we connect to our passion, that in itself will be regenerative; we won't have to wait for the energy, it will be there. But how do we connect to that passion? One of my favorite phrases, which a friend taught me, is that we need to pay 'exquisite attention' to our responses to things — noticing what makes our flame glow brighter. If we pay attention to those things, we'll be able to catch the flame and feed it.

Sometimes I think we need to get out of our routine, to get out of our pattern, to talk to people we wouldn't normally talk to. Change jobs. Move away. Gather up some friends, go outside, and play football, instead of playing Madden NFL 06. Take it upon yourself to change something about your day. Anything. Even if you have a bad experience, you will have had an experience. You will have learned something that you can take with you next time. And if you have a good experience, remember what gave you the feeling and do it again. Soon.

Technological mediation isn't going to go away. In fact, it's only going to become more pervasive. At the most basic level, technological mediation creates an illusion. When augmenting our experiences, it makes us feel closer to our environment, but it obstructs them by adding a layer of abstraction between us and our environment — the latter of which when often do not notice or just forget about once the technology has been assimilated into our world of media. As Pat Califia puts it, "We have to find a way to synthesize the rhythms of nature with our electronic lives. A fuzzy-headed, sentimental longing for bucolic utopia will not save us from toxic waste or nuclear weapons. We need a world where we can have both computers and campfires." Indeed, from language to advertising to technology, all of our experiences are mediated to some degree. We just need to be more mindful of what constitutes authentic experience, find a path through our mediated world, find a balance, live without dead time, live an authentic life without artifice.

Image by Roy Christopher.