Much has been said about Carl Jung over the years, and despite the fact that many now in psychiatry and even some therapists seem to find him irrelevant, the amount that has been written about his ideas belies this claim. So much as is possible in a short article, I would like to consider his contribution as well as provide a possible critique of some of his thought. Through that I hope to highlight the value of relating to symbols as psychological facts.

I was in a house that I did not know, which had two stories. It was “My House.” I found myself in the upper story, where there was a kind of salon furnished with fine old pieces in rococo style. On the walls hung a number of precious old paintings. I wondered that this should be my house, and thought, “Not bad.” But then it occurred to me that I did not know what the lower floor looked like. Descending the stairs, I reached the ground floor. There everything was much older, and I realized that this part of the house must date from about the fifteenth or sixteenth century. The furnishing were medieval; the floors were of red brick. Everywhere it was rather dark. I went from one room to another, thinking, “now I really must explore the whole house.” I came upon a heavy door, and opened it. Beyond it, I discovered layers of brick among the ordinary stone blocks, and chips of brick in the mortar. As soon as I saw this I knew that the walls dated from Roman times. My interest was by now intense. I looked more closely at the floor. It was of stone slabs, and in one of these I discovered a ring. When I pulled it, the stone slab lifted, and I again I saw a stairway of narrow stone steps leading down into the depths. These, too, I descended, and entered a low cave cut into the rock. Thick dust lay on the floor, and in the dust were scattered bones and broken pottery, like remains of a primitive culture. I discovered two broken skulls, obviously very old and half disintegrated. Then I awoke.

In this dream, the house is built up in layers, a level and room atop the next, and it later occurred to him that these showed an ideological history which shaped his thought to that point, but in which he was also an active participant — the basement was built upon by the first floor, and so on, just as the “primitive” world was, according to this narrative, proceeded by the dark ages and Christian eras that were quickly losing power by the late 1800s.

To his thinking, this dream demonstrated the way that what he calls the collective unconscious overlaps the personal one, or perhaps how it is all a progressive shade of grey without a single defining line, save the ones we bring.

We can at this point move away from his own interpretation to consider it in its own context. The specific history this dream lays out is in fact quite telling, as it is at least one vantage point of Jung’s sense of his own collective history, the history of western “progress.” A linear history, such as one presented within a worldview or ideology as the Enlightenment, is also a narrative. In fact, in literary analysis, the basis of narrative is generally understood as just that: the narrative skeleton is the collection of facts in a particular order. From the choices made in terms of which pieces to value, and in what order they are presented, one’s authorship is defined. The final flesh would be style, meaning, and the aesthetics that reflect back at the surface.

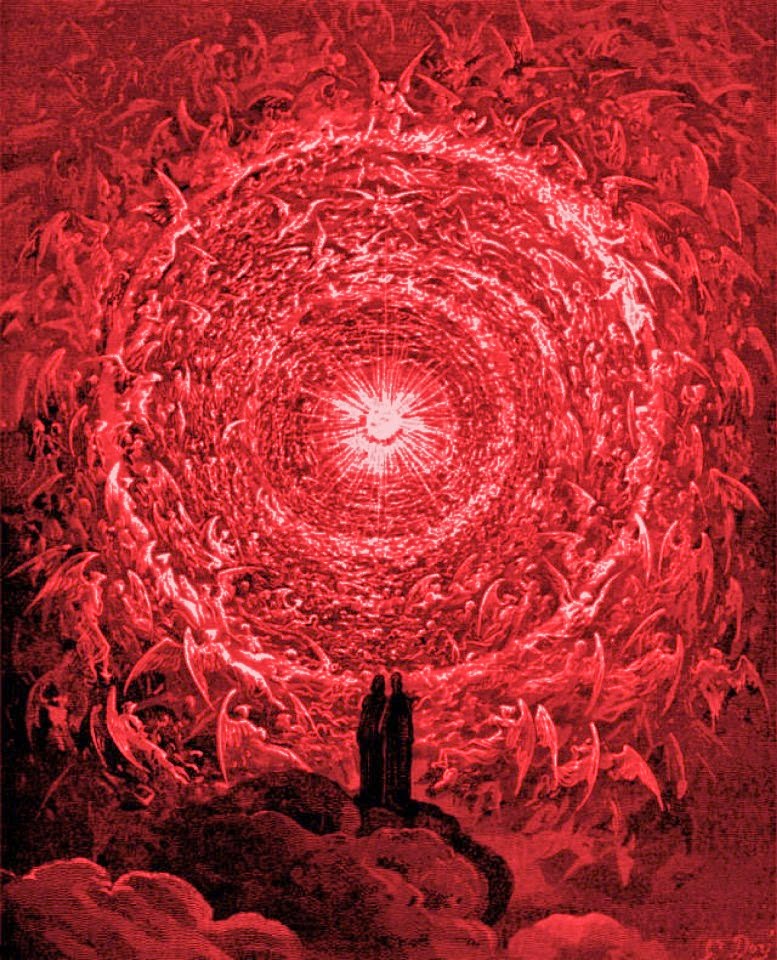

He chose to interpret a room in a multi-level house in terms of a cultural history of religion, industry, and colonialism, and that those strata should be arranged in such and such a way. (Chronological-historical is not the only way to arrange a narrative, indeed, our experience of life is multi-threaded and non-linear. For example, as you walk down the street you think of a song from your youth, you laugh and it makes you think of a school dance ten years later, then you hear a car honk in the moment, and it puts you in another time. Meditation is such a challenge in part because it seeks to make our time-travelling more at our will, rather than the whim of our unconscious). It may even be a symptom of the Enlightenment ideology to hang Foucault’s pendulum in the center of the city of one’s birth and arrange the whole world round that psychological center. This was frequently the metaphorical-spatial sense he used when creating symbols, as we see in the layout of his mandalas or the quadripartite ‘types’, or the many other circular center oriented symbols he uses as guides.

So we can see that Jung’s thought is in some sense structured by the meta-narratives of the Enlightenment, and one might expect to see this structure the process and stated goals of his approach to psychology, which he clearly defines as the striving for and attainment of individuation.

These aren’t isolated incidents. The biases of the Enlightenment run through all of his work, even more than the light and dark of the religious or industrial myths that were more germane to his place and time to some extent, excepting the obvious influence of a particular version of Enlightenment ideology that entered the German speaking world in the 20th century. He seems to mostly share its ideals, and its perspectives toward other cultures, for instance the concurring idyllic, somewhat romantic image of women (wherever well and ill dignified.) This is helped little by the fact that archetypes, which factor heavily into his analysis, are by their very natures sort of symbolic cliches; but they are cliches that have retained their psychological power. In fact it is precisely through all that psychological common ground that they gain their “manna” so to speak.

Before going on, it’s worth saying that we might recognize much good about the Enlightenment, especially in its ideals. It not only paves the way for the transition from the medieval world (built atop what he calls “primitive society”) and modernity, but also prioritizes the scientific method in intellectual matters. It is characterized in fact by this kind of optimism that the faculties of human reason can overcome all obstacles. However, it was also the cultural force that supported rampant colonialism, and in the path of paving that route to industry, re-enslaved much of the world. This would be, in his terms, its shadow. And so, by extension, it is a part of his as well.

Some credit is due, for unlike Sigmund Freud, Jung seemed aware of the possible dangers of the psychological imbalance presented within this ideology — much as each individual in his thinking has a prominent mode, whether thinking, feeling, sensing or intuiting, so a given group consciousness might present the same. For instance, the following passage from Memories, Dreams and Reflections shows some of the history bound up with Enlightenment optimism.

“We always require an outside point to stand on, in order to apply the lever of criticism… How, for example, can we become conscious of national peculiarities if we have never had the opportunity to regard our own nation from outside? Regarding it from outside means regarding it from the standpoint of another nation. To do so, we must acquire sufficient knowledge of the foreign collective psyche, and in the course of the process of assimilation we encounter all these incompatibilities which constitute the national bias and national peculiarity.”

When speaking with Ochiaway Biano of the Pueblo Indians, this seems to come together most clearly:

“See,” Ochiaway Biano said, “how cruel the whites look. Their lips are thin, their faces furrowed and distorted by folds. Their eyes have a staring expression; they are always seeking something. What are they seeking? The whites always want something; they are always uneasy and restless. We do not know what they want. We do not understand them. We think they are mad.”

I asked him why he thought the whites were all mad.

“They say that they think with their heads,” he replied.

“Why of course. What do you think with?” I asked him in surprise.

“We think here,” he said, indicating his heart.

I fell into long meditation. For the first time in my life, or so it seemed to me, someone had drawn for me a picture of the real white man…. I felt rising within me like a shapeless mist something unknown and yet deeply familiar. And out of this mist, image upon image detached itself: first Roman legions smashing into the cities of Gaul, and the keenly incised features of Julius Caeser, Scipio Africanus, and Pompey. I saw the Roman eagle on the North Sea and on the banks of the White Nile. Then I saw St. Augustine transmitting the Christian creed to the Britons on the tips of Roman lances, and Charlemagne’s most glorious forced conversions of the heathens; then the pillaging and murdering bands of the Crusading armies…. What we from our point of view call colonization, etc., has another face — the face of a bird of prey seeking with cruel intentness for distant quarry — a face worthy of a race of pirates and highwaymen.

So it is somewhat unfair to dismiss his work entirely for presenting a historical or ideological bias, especially since it is absolutely impossible for any writer or thinker to do otherwise, unless they deal purely in the realm of axiomatic fact without adding a shred of their own perspective to an analysis. Nevertheless, some particular repercussion of these biases is frequently used to dismiss the Jungian approach entirely. I raise this brief critique of Jung for the opposite purpose — to help contextualize his work and emancipate his ideas from his corpse. As with anyone, he must be a product of his time. In a sense, none of our work can be seen for its self while we still live and block its light. But in that post-mortem unveiling of a life’s work, it is just as common for it to be misunderstood or shoved aside.

Fritz Perls may have had the Jungians in mind when he objected that ‘many psychologists like to write the self with a capital S, as if the self would be something precious, something extraordinarily valuable. They go at the discovery of the self like a treasure-digging. The self means nothing but this thing as it is defined by otherness.

By taking the Self seriously, in other words, in applying what is often seen as a lightly Buddhist-influenced, “oriental” approach to psychotherapy, to a philosophy that contradicts a very important tenet of Buddhism — that the self is transient to the extent of absolute phantasm — there is, no question, an ideological bias. Libidinal hangups seemed to lead Freud to an obsession that blocked all in its path; Jung discusses his growing horror in recognizing this in his friend ranting about “the world being consumed under a flood of occult mud.” In Jung, what we are seeing is not so much a holdover of Enlightenment thinking as a central part of a gnostic ideology. Jung was perhaps most profoundly influenced by a variety of gnostic and alchemical texts, and it was in this research that the true significance of symbol as indispensable psychological tool was seen.

As is often the case, the worst in someone or something, from a certain perspective, yields the very best it has to offer, from another. It is my opinion that the gnostic current provided his most interesting insights.

Further, it is in Carl Jung’s willingness to consider so-called paranormal activity, UFOs and so on, as well as in his willingness to consider literary and artistic symbols within the same context as all experience that his work has at times been used to support a sort of “loose thinking” that he would have likely found abhorrent.

Before we can look at this insight, I’d like to tie off this point about Enlightenment ideology. A critique of Jung’s theories might also make us ask how we might entertain so-called “Jungian ideas” independent of his writing. This is the project undertaken by many groups such as the PAJA, though in such organizations one often sees a conflict between truth toward the source and a question of what direction to move forward, if that work isn’t merely a collection of museum pieces. What might the Jungian method look like when used from a different ideological / historical context? How might we unmoor it from the precepts of the Enlightenment?

The general narrative (which itself might be called a product of Enlightenment thinking) is that following the Enlightenment came the Industrial Revolution, and hard upon that came the World Wars and Postmodernism. It is natural to consider the postmodern / ideological re-terrialization in the West, namely the transition from the centrally arranged quadripartite city and self model, so well emulated in Jung’s interpretation of the Mandala process, to the post-modern city that has no center. In other words we might consider Jung’s model of the self as similar to the planned city of the 18th-early 20th centuries, while we have since been presented with models that see no centralized principle. (Of course plenty of “organic” cities like London and Boston have followed the supposedly organic growth process long before the 20th century, and most cities actually contain a mixture of planned and naturally grown structures.)

This raises a significant problem. Are we still in the post World War Two anxiety? Is post-modernism really the End of History? I’m not personally satisfied with leaving ourselves in more or less the same condition as the psycho-historical framework that was punctuated by the mutual annihilation of modernity in the fires in Dresden, the death camps, or the leveling of Hiroshima. Psychology is always rooted in history, but what it reacts to is rarely clear to the conscious mind except in retrospect.

Unfortunate we must raise some of these questions without being able to answer them in a simple way. The present is, in some sense, always the End of History. At this very moment we too are subject to a new structural model, a force of mythic history and culture, and are under the sway of myths that flow from that schema, but we can’t see it yet. Not entirely, although it is up to the artists to help us see the contours of that narrative.

In other words, it is precisely because we are no longer living in Jung’s time that the bias that was naturally invisible to him should be all too clear to us. But we must beware the ever-present delusion that we live at the end of history when we are instead merely standing in its shadow. This perhaps shows the clearest distinction between what we might call narrative and myth. Myth seems to originate from the past, and yet if it is still living, we remain in its wake. A myth too is a type of narrative, but it is much more common for us to use the word “narrative” to refer to what is immediately under our noses. (I have certain discomforts with such pat distinction and simplistic analysis, but exploring that would too easily lead us off topic.)

Before moving on to what is, at least to my mind, Jung’s greatest contributions, we should also provide a final critique, in similar terms, about the Enlightenment concept of gender, and how this can impact the psychoanalytic process. This too could easily be the topic of a book in its own right, but suffice it to say there are ideas about the roles, psychology, and innate desires of the sexes which were the result not of material fact, but rather cultural stereotype.

In other words, gender essentialism was the norm, and heterosexuality was generally considered the only healthy and logical sexual expression. You see evidence of this in Jung’s otherwise apt schema of the anima or animus, the anima being the female projection of the male, and animus of the female. There is little flexibility then, as now in some circles, regarding different family or sexual relationships, and therefore little consideration of how these might structure the patterns of the psyche, short of the bigotry of the inherent pathology of the homosexual, etc. Despite this rather glaring issue, there is a surprising amount of experiential support for at least the general shape of the anima/animus concept, and that confirmation is in itself a demonstration of psychological validity in the sense of symbols, though not in any way of some kind of underlying or objective truth.

The distinction between these two senses of the word ‘truth’ point us toward the heart of the matter: tossing out an inquiry because it raises psychological discomfort is precisely the kind of behavior that will forever keep us in the dark about ourselves. Problems of this sort don’t point to falsity, but instead to a particular type of truth in the form of psychological energy, which is almost without fail tied up in paradox and contradiction.

We should not therefore discard Jung’s schemas as out-of-date relics. There are many corollary reasons but I will sketch out two, as well as outline related concepts:

1. Functional Appropriation. Jung had a talent for creating relatively simple, functional psychological models (“schemas”), which are straightforward enough that they have often entered the common modern lexicon. For instance, introvert/extrovert, the four-way or quaternary arrangement of the self types, the shadow — these are all dangerously practical ideas. I say dangerously because they are often so straightforward that people seem to frequently treat them as facts in themselves, despite Jung himself being quite clear that all schemas are merely inventions so we might get any kind of handle on what might be a completely muddled mess otherwise. So the self may not “actually” have four parts or be organized around a central point; certainly you won’t find any indication of that in the structure of the brain, nor will we find the symbolic illustration of the chakras in our spines.

It is precisely this organizing principle that is under critique in this article, not because it is flawed, but because we cannot create a schema without giving away our cultural bias and position in history. The best we can do is be aware of it.

2. The Central Role of Symbols In The Psyche. Jung’s greatest contribution is sadly also his most overlooked, outside those that are explicitly following from his work. This is the crack he opened in the impenetrable divide between science and myth, which Joseph Campbell further explored and popularized. This is the recognition that all symbols are every bit as “real” as any other phenomena, as they are all psychological experiences first and foremost. This does demand an active discernment between those things known also through axiomatic, so-called objective experiment — but it does not in itself provide a hierarchy of value, only a fundamental ontological distinction between a proton shot through gold foil and the tentacles of a sea monster encountered in dream. But those who dismiss the latter as merely empty fantasy will be cursed to never know themselves, and so we see the outline of the present cultural dilemma, where we learn more and more about the external world, and know ourselves less with every turn.

Jung was aware of this problem, and was quite frank about it in the final chapters of Memories, Dreams, and Reflections. The language and schemas of psychology are confused and misunderstood (especially in pop cultural portrayals), by the fact that all pathology that doesn’t seem to arise directly from biological morphology or genetics is processes that occur in nearly every human psyche in some form. This has been commonly observed in the introduction of psychological “abnormality.” In other words, pathology is simply “normal” process that is out of proportion or unbalanced, and even then we can only evaluate that in relative terms of what is culturally accepted. This is most clearly demonstrated with so called cultural illnesses, psychological “disease” that occurs only in one culture. (See also: Cultural Illness and the Curse of Shifting Sands.)

However, diagnosis as well as symptoms may vary from group to group, and so here too is a very large philosophical issue within psychology that is often brushed under the rug as a curiosity.

Narrative and myths play a principal role in our lives from the inside out (sense- and identity-making), and from the outside in (narratives place ourselves in relation to one another, conceptualizing the structure and nature of the outside world), and they are self perpetuating (narratives as pedagogical or even mimetic device).

If we have any doubt about the centrality of narrative in our extended, communal, and personal lives, one need only turn on the news or witness how, without changing one’s own behavior, another may change their story from how amazing and wonderful you are to how awful and villainous. What has changed in this case except their internal narrative? The levels and dimensions of this process are quite simply endless, and try as we might to extricate ourselves, it is our investment in a particular narrative over another that defines belief.

For all these reasons, I see Carl Jung as an important beginning to a conversation on symbol, self and the psyche which in no way ended with him. In fact, this topic is still in its infancy, at least insofar as it has been adopted and understood by the majority of the world. Yet nothing is more desperately needed, as so long as we misunderstand the psyche, we misunderstand one another, and so long as we do that, atrocity is inevitable.