The following is excerpted from Magic in Islam by Michael Muhammad Knight, published by TarcherPerigee, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC.

An attempt to examine the question of “astrology in Islam” might first ask if Muslims are doing anything unique: If there is in fact an “Islamic position on astrology,” is this position especially Islamic for any reason other than the sources cited and authorities to which one appeals? Can something be gained by carving all Muslim responses to astrology from their respective contexts and isolating them within the category of Islam? Does this actually paint a helpful picture of anything? Or does the category show its incoherence and start to disintegrate before our eyes?

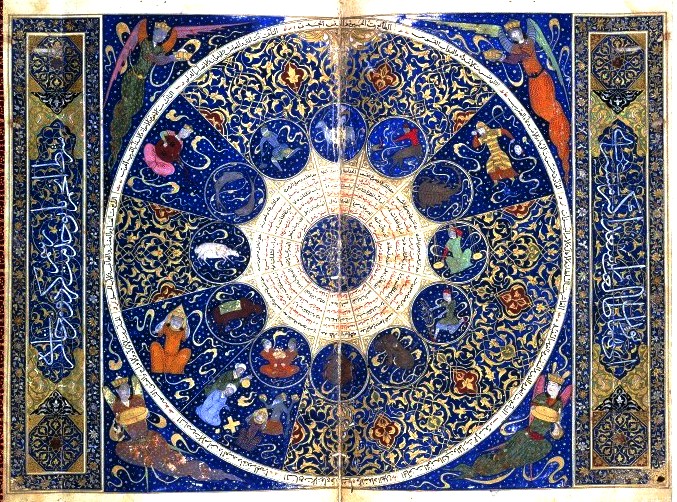

Though now closer to the “magic” section of the bookstore, astrology once enjoyed the full prestige of science, and the assumptions upon which astrological traditions rested were widely accepted—even by astrology’s most vehement opponents—as basic facts of nature. At another point in history, everyone knew that the earth occupied the center of a series of spheres, that these planets were embedded in the spheres, and that in our own sub-lunar realm, we were subject to the effects of forces moving in those spheres. Because there were seven planets—according to a definition of “planet” that included the Sun and Moon, but not the earth—there were seven celestial spheres, all existing within an outermost sphere that encompassed everything. Depending on one’s precise religious orientation, these facts produced different consequences. But the consequences are too varied for us to name the “Islamic position” on astrology. Even if a Muslim accepted as valid the prophetic statements that prohibited the knowledge of stars as a form of detestable sihr, this acceptance could still signify different openings and closures to different readers. Some Muslims regarded astrology as a kind of polytheism; others believed that astrology provided special evidence of harmony between heavens and earth that served to prove divine unity, the uncontested sovereignty of a shared creator and lord. There were even claims that astrological analyses of history proved Muhammad’s prophethood. Some Muslims acknowledged astrology’s˙ potential efficacy, but rejected the field as having originated via humans learning from jinns or demons. Their fellow Muslims, however, could cite alternate sources that repositioned astrology as having originated with genuine prophets who received this knowledge as divine rev-elation. And while the Qur’ān makes several references to stars without ever giving a clear verdict on the issue of astrology, both astrology’s opponents and its supporters have cited the Qur’ān in support of their opinions.

While theologically driven opposition to astrology can be found in any period of Muslim history, believers who engage astrology today are likely to be accused not only of bad religion, but also of bad science. Astrology has surrendered its scientific gravitas, but believers continue to argue that science is on the side of their faith. Muslims disseminate pamphlets and Web sites attempting to prove that the Qur’ān contains miraculously advanced scientific knowledge regarding matters such as fetal development and ge-ology. Christian opponents of evolution do not only counter Darwin with a valorization of blind faith in scripture, but have produced a sizable industry of textbooks, films, and even museums that claim to scientifically prove their scriptural creation narrative.

Beyond natural sciences, religious adherents will play by the rules of dominant knowledge regimes even when attempting to refute them. So apologists for patriarchal norms might counter feminism by using arguments that only feminists made possible, i.e., defending conservative gender restrictions as empowering and liberating for the individual woman of faith against sexism and objectification that exist in broader society. Neotraditionalists can disdain modern critical theory but might pick up enough of it to wield against their opponents, without ever turning that tool upon their own assumptions about the “classical tradition” that they claim to know and represent.

The various rises and falls of astrology throughout history point to the instability of religions that we imagine as timeless and unchanging. In some historical settings, astrology provided a useful resource for proving one’s own religious claims against whoever one marked as unbelievers, or clearly establishing God’s favor for one empire against another. Different fields and methods have supplanted that resource, and I wonder if any tradition can survive these seismic shifts and remain the same tradition.

Modern believers in any premodern tradition conceptualize the universe in ways that would have been unthinkable to their predecessors. Our ideas about the structure of created existence would make no sense to our coreligionists from previous eras, and perhaps not even to foundational and prophetic figures of the traditions that we claim. Is it the same Islam? Does Muhammad’s celestial ascension through the seven heavens preserve its “traditional” meanings and consequences if we no longer uphold these seven heavens as the actual organization of the universe? And what are the consequences as we claim the authority over our traditions to decide when premodern theologians, philosophers, mystics, or jurists speak only within the limits of their own world’s science, as opposed to their universal and timeless truths?

If a consideration of Muslim astrologies throughout history points to the instability of Islam as a construct, it also challenges Islam’s pristine purity and self-containment against other tradi-tions. Astrology was a shared technology that crossed boundaries of faith confessions. Muslims, Christians, and Jews were doing similar things with the stars and actively informed each other’s projects. This is in part because they shared similar conceptions of how the universe was ordered—and not only because they were all “children of Abraham,” but perhaps more so because they studied the same corpus of scientific works, much of which was written by polytheists, and ascribed to shared sets of assumptions within their historical settings. Theophilus of Edessa (d. 785), a Christian who worked as court astrologer for the ’Abbāsid caliph al-Mahdī, calculated that Islam was to last 960 years, the amount of time that it would take for the Saturn-Jupiter conjunction to reappear in Scorpio. In the early twelfth century, a Jewish astrologer in

Spain calculated that in the year 1226, a great Saturn-Jupiter conjunction in Aquarius would correspond to the disappearance of both Christianity and Islam from the earth and herald the appearance of the Jewish Messiah.50 His work relied on a tradition of conjunction-based prediction astrology that had been championed in Muslim caliphates, with its formative thinkers in the ’Abbāsidera being the Jewish astrologer Mashā’allāh and al-Kindī’s Muslim/atheist disciple, Abū Ma’shar, who themselves worked with a pre-Islamic Persian legacy of reading kingdoms’ rises and falls through Saturn-Jupiter conjunction theory.

Because we are products of our own historical moment, Muslim beliefs today sometimes have more in common with the views of contemporary adherents of other religions (or even secular humanists!) than with Muslims from other periods. For those who mark consistency as a religion’s first claim to legitimacy, this could be unsettling. To consider a field such as astrology and recognize its changes throughout Muslim traditions subjects Islam itself (along with the traditions imagined as Islam’s “Abrahamic” cousin faiths) to the possibility of change. Meanwhile, taking a close look at Islamic astrology as a concept reveals Islam to be continually remade in collaboration with other traditions, denying the suggestion of a clear and stable “inside” that can ever hope for protection from the “outside.”

***