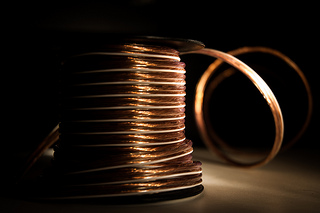

In the 1940's, Emery Blagdon began making "pretties," his name for the copper-wire wrapped hangings he created in his free time. Little is now known about Blagdon's life, which was ordinary by all accounts. Blagdon was born in 1907, and spent the Great Depression years riding the rails. He inherited his uncle's farm in North Platt, Nebraska in the 1950's, which is where he spent the remainder of his life expanding on the creation of his "pretties."

Blagdon worked the land only enough to provide adequate food for himself and his family. He spent his spare time working in a shabby shed and workshop he constructed behind his family's home. Here, he began to actualize his vision of a Healing Machine. Blagdon, who lost both his parents and three younger siblings to cancer, believed himself to be particularly sensitive to electrical currents. He wanted to create a machine which could conduct these currents and promote healing. He eventually crafted more than 400 complex and intricate pieces for his Healing Machine, which were each made up of an array of components, some of which included batteries, TV and radio parts, paintings, wire hangings, paint can lids, magnets, lightbulbs, painted popsicle sticks, boxes of found materials, coffee cans, and much more. This chaotic mix of ingredients somehow combined to make a room that looked like a work of art, but served a purpose: healing with electrical currents.

The Healing Machine in Blagdon's backyard shack featured a false floor, concealing networks of live charged wires. The false floor also helped the Healing Machine draw energy from the earth beneath it. Many said there was a palpable energy in the air that would make your hair stand up on end.

The paintings Blagdon created were geometric and colorful. Instead of being hung, though, they were arranged in unusual ways, sometimes face-down on the floor, and other times placed in stacks facing each other. Blagdon believed each unique placement helped better conduct the electrical currents.

Blagdon, who grew increasingly reclusive in his older age and was afraid shaving or cutting his hair would lead to his death, consulted Dan Dryden, a pharmacist, about obtaining conductive "elements." Dryden supplied him with various salts and crystals, and remained interested in Blagdon for the rest of his life. When Blagdon finally succumbed to the cancer that had been ravaging him for years and for which he never sought treatment other than his Healing Machine, Dryden banded together with a group of friends to purchase the Healing Machine from Blagdon's estate.

Dryden and his friends were the keepers of the Machine for more than 20 years. Now, much of it has found a home in the John Michael Kohler Arts Center in Sheboygan, Wisconsin, where it rests in good company with other incredible examples of non-formally trained art, sometimes referred to as "folk" or "outsider."

When Blagdon finished the Healing Machine, he invited people from the community to come and sit in it to receive physical and psychological healing. Dryden says this of his experience in the Machine:

"He [Blagdon] opened this door and reached around the corner, threw on a couple of switches. All the Christmas tree lights came on. Some stayed on. Some were blinking on and off, reflecting off hundreds and thousands of pieces of copper wire, tin foil, painted tin can lids. It hit me all at once. This panorama — even though it was a small room — it looked like a vast panorama … the room looked ten times larger than it was … [J]uxtapose that with the fact that outside there are miles and miles of nothing but Sandhills, a few corn fields, a few cattle, otherwise absolutely nothing – and here [was] this whole world, contained within the shed …"

For a mind-boggling look inside the Healing Machine and for more information about its individual components, watch this YouTube video.

Image by Thomas Grooms, courtesy of Creative Commons licensing.