After the flood, after the Halloween hurricane stranded us in Brooklyn, sent our Lower East Side allies scrambling northwestward with their sudden pillowcases of manuscripts, after the tidal surge and the wild wind ravaged Staten Island, left our students in the Bronx without electricity, gave the better half of Manhattan neither power nor heat nor access to food and water, and generally made a joke of overpriced matchstick construction in three states, after the grid came back on, a few of us gathered on MacDougall Street to celebrate the comeback of Babylon for the present and to discuss what must be done.

De Zondvloed is Dutch for “the flood,” I think. Don’t hold me to it. The important thing in the present context is that our host for post-blackout Sunday lunch, a Dutchman, spoke of the flood with particular authority. His folks have been dealing with threatening ocean levels, big river deltas, and tidal surges since medieval times.

I paraphrase my friend here from memory. The present storm damage in NYC is nothing. There will come a total submergence of Manhattan Island. Then we will do something. We will build a series of gates to isolate the harbor from the sea. We will build channels upstate to divert the Hudson River’s down-flow outward to supply farmers, towns, and villages with our excellent mountain water for free. We can distribute our water for agriculture, fish farms, bathing ponds and general aqueous delight or we can let it kill us.

It’s a complex engineering with a tested 1000-year history and proven precedents. It’s been done, just as universal healthcare has been done.

We’re not talking about some obscure metaphysical voodoo here. We can provide health care, higher education, jobs, affordable retirement, gaiaelectrics, and local food production to everyone while preventing the rivers and oceans from uniting to drown us like rats while the deserts join to kill us with drought. We already know how to balance these elements. We know the math, the dynamics, the metallurgy, the engineering, the chemistry, the biology, the crop science, the animal husbandry, the shit fermentation specs and the financing. It’s been calculated down to the level of the boson. Let’s go.

When I was 18, my science teacher made me go to a classroom presentation by a guest lecturer who said that we could, without extracting any more resources from the earth than we already have, provide every man, woman, and child on earth with a higher standard of living than any being on earth presently enjoys. The guest’s name was Buckminster Fuller.

The extraordinary thing about the administration of what we call “America” is that the currently-powerful white men whom we call legislators are mostly from rural areas and smallish towns. They have little clue about global issues and even if they had a PhD in geopolitics and a warm spot for our mother, they would still be dependent for their careers on some fairly poisonous local interests. This was true a hundred years ago when we began to emerge as a global power and it is no less true today. Men with narrow backgrounds and largely parochial interests are making decisions on world-impacting policies while their careers are dependent upon coal bosses, fertilizer companies, and oil speculators.

As the National Lampoon put it forty years ago, “the shitheads are running the show.”

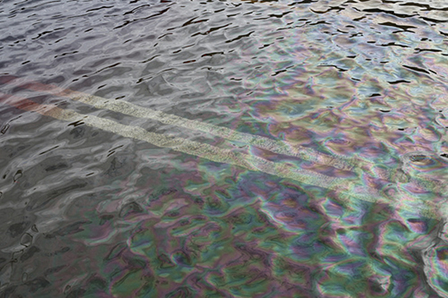

Here in New York, we live on a delta that sits between northern and western mountains that drain a rainy region. This means big-time outflow from the continent to the sea, right now, outside my bedroom window, into my garage, and up to the ceiling in my friend’s downtown office. Let’s face it, we are a stepping stone across a waterfall that meets an ocean. How many billions of gallons-per-minute flow in conflicting directions? Where’s my I.V.?

Fuller told my science class that the problem is who’s in charge. He wanted to put the scientists in charge. Can we do that? Only if that means that everyone must become a scientist. This reminds me now that J. F. Lyotard says it’s not enough to be an artist; you also have to be a philosopher. Bucky and Jean-Francois are right. Now is the time of gnosis. Our civilization, culture, whatchamacallit, has made a multi-century commitment to liberation through knowledge. We’re stuck with it. I’ll trade you Simone DeBeauvoir’s Ethics of Ambiguity for Leonardo’s studies of fluid dynamics. K? THX.

I am not a native here. I come from a country where the larger environmental forces are, of long-learned necessity, respected to some extent. We’re far from getting it quite right, but we don’t build or heat with wood, for example. Wood was a material of convenience. It’s gone, baby. The “boardwalk” is a uniquely American phenomenon that testifies to America as the land of late, great, and final waste.

The “Jersey Shore,” and the cities of the west coat, San Francisco, Los Angeles, looked to me from the first as though they were begging to be blown away. That’s why I love them. They are fragile and self destructive, like all my favorite people.

Humans make heat and structure with wood until it is exhausted, then they move to other materials. In many places where trees are no longer available, they burn and build with dung. Maybe the Atlantic City boardwalk, Staten Island, Rockaway and the south shore of Long Island and Connecticut should be rebuilt out of excrement. Two birds with one stone, as they say.

After the Halloween hurricane, in the hardest hit areas, the first institutions to be restarted were the casinos and the Stock Exchange. Dig that. The city says 40,000 people need shelter tonight. That’s on top of the 100,000 homeless who already haunt this archipelago. The mayor said we wouldn’t let the lost homeowners of beach front properties go homeless. Where was that caregiving impulse when, in the 1980s, the deinstitutionalization of insanity puts thousands of mental patients on the streets?

Only love can make the rain; love, rain on me.

Image by WarmSleepy, courtesy of Creative Commons license.