As most of us know, the human race has been using psychedelics for centuries, and those original uses were rooted in spirituality, ritual, and medicine.

The Babongo tribe of Gabon in Central Africa utilizes the bark of the iboga plant in Bwiti for rites of passage, communal events, and personal spiritual growth. Ayahuasca is used for emotional and physical purging in the Andes and Amazon regions of South America. In Aztec and Central Native American cultures, peyote was used in communal events for emotional enlightenment, in the pacific islands, kava is practiced for both sacred and social situations, and in Mazatec practice, psilocybin is consumed for healing rituals.

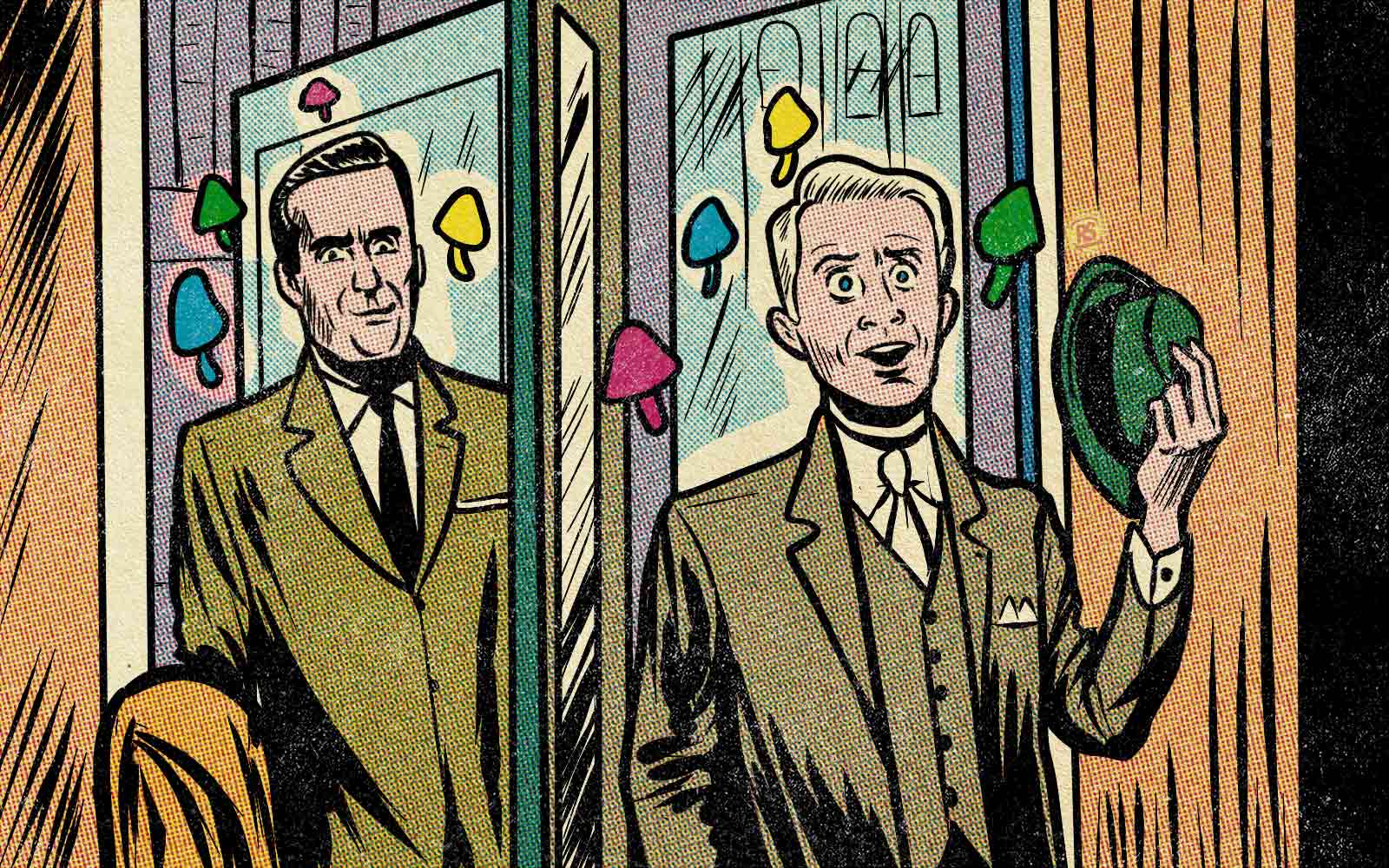

So how did psychedelics go from spiritual and communal events guided by shamans to becoming a cog in the Western corporate machine?

The gentrification of psychedelic culture has been taking place for a very long time. Not only can it be culturally exploitative of these traditions, but it can bear a threat to the ritual itself — we see this in tourism a lot. In a National Geographic article, Hannah Lott-Schwartz writes: “The draw to the substances is so powerful that it’s also compelled interested outsiders to become active partakers, creating a whirlwind of well-documented drug tourism, and, consequently, the commercialization and commodification of religion, threatening not only the practices themselves but also, in some cases, the plants central to them.”

But it’s not just tourism that appropriates the psychedelic cultural importance — capitalism is around the corner too. Psychedelics in America are being pulled away from the fringe, stripped of their cultural significance, and pushed into the mainstream. We have more pop culture surrounding the use of psychedelics, and we also have more scientific explorations of how substances like LSD and psilocybin can be integrated into Western medicine to help heal and treat ailments.

Before we go further, let’s look at the definition of gentrification: “the process of making someone or something more refined, polite or respectable” (right from the jump, it’s pretty problematic to suggest that sacred cultures that have been around for thousands of years aren’t respectable or refined, but we digress).

In the case of businesses, we can absolutely see that gentrification exists in things like development companies investing in compounds that don’t cause bad trips or opportunists flocking to the industry for lucrative employment prospects. According to Lewis Goldberg, managing partner for KCSA, it looks like the foundation is being built for a multi-trillion-dollar industry.

Rolling Stone expands on other potential business ventures within the industry: “Indeed, it’s not just those developing the drugs who will be in on this industry — careers will span from lawyers who specialize in helping entrepreneurs navigate the legal landscape, to therapists who help patients integrate their experiences after a psychedelic trip, to receptionists who greet visitors at psychedelic clinics across the country.”

By making psychedelic products more palatable for the masses, businesses can make more money. And this is a double-edged sword. The plus side: commercializing psychedelics could lead to more inclusive laws, legalization and decriminalization. The downside: mass-production and mainstream marketing rarely go hand-in-hand with cultural reverence. In fact, we can already see more funding going toward corporations rather than grassroots-style of businesses.

There are those who are trying to nip this attitude in the bud, however. Charlotte James, co-founder of The Ancestor Project, an educational platform offering plant medicine journey resources and workshops that are designed for people of color, says, “This will require a lot of personal and internal decolonization work by the emerging ‘leaders’ of this space. We believe that by doing this work first, it then becomes natural to understand your role in the collective liberation movement that this medicine wants us to usher in. An equitable ‘industry’ won’t be an ‘industry’ as we currently understand it to be, and instead, a mycelial-like network of co-creation across diverse communities and environments.”

James also touches on how a hyper-focus on productivity will negatively impact psychedelic culture, both in a traditional and modern sense. “In order to move away from capitalism, we have to break the work patterns that are ingrained in us… Those patterns that contribute to the glorified ‘hustle and grind’ culture are actually just extensions of systemic oppression. Reclaiming our relationship to creativity and productivity will support us in being able to imagine a different and more equitable future in which our value is not defined by our bodies or our productivity.”

This paradigm shift will take work from both employees and employers too. At Magic, a marketing agency for the psychedelic space, CEO and co-founder Gareth Hermann lists the company value of “bringing your full self to work.” Magic’s Chief People Officer, Jennifer Ellis explains, “At Magic, we don’t like the term ‘balance’ because it brings up the image of being on a seesaw, so we’re creating a culture that’s more celebratory of work-life ‘presence’ to create a space for the whole human to show up at work.” Refreshingly, Magic actually offers support for their employees on making this happen by offering repatterning programs and resources.

Mike Margolies of Psychedelic Seminars is another voice that’s calling attention to how a shift in how we view productivity could be healthy for people inside or outside of the psychedelic space. “It’s crazy that [the 40-hour workweek has] become the standard,” Margolies says. “The goal isn’t to get everyone working, but how do we get everyone self-actualized? Achieving collective self-actualization is intrinsically the pathway to creating the most value for each other.”

There’s a lot of work and conscious effort to be done if we want to keep psychedelics from getting lost in the productivity-obsessed clutches of capitalism, but it is possible — and worth it.