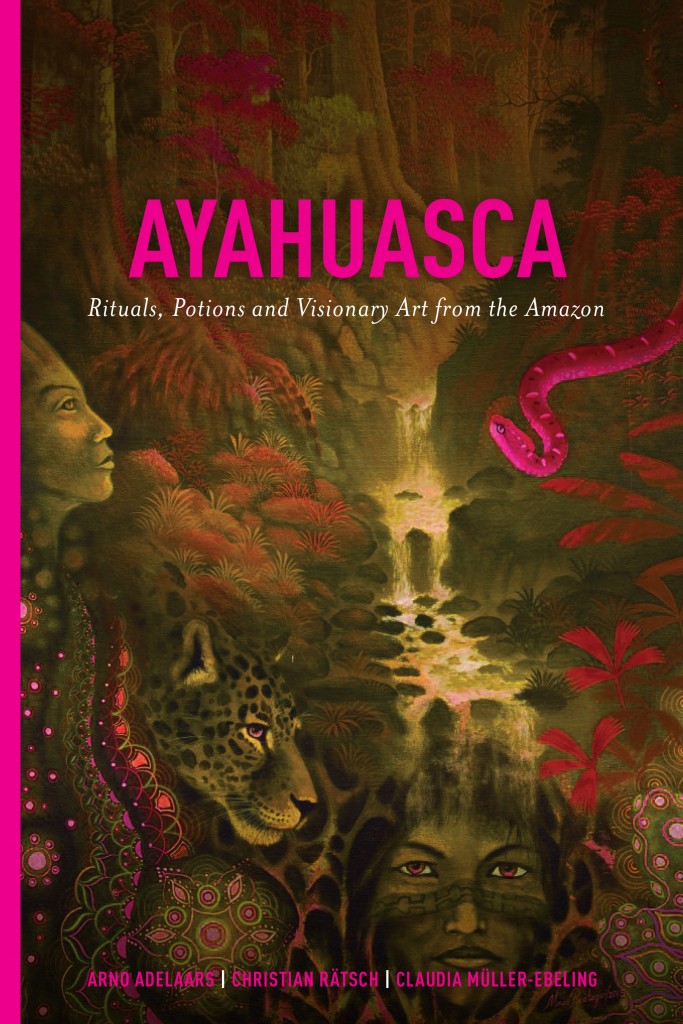

The following interview is excerpted from Ayahuasca: Rituals, Potions and Visionary Art from the Amazon, edited by Arno Adelaars, Claudia Muller-Ebeling, Ph.D, and Christian Ratsch, published by Divine Arts Media.

Hilario Chiriap is a traditional Ecuadorian shaman from the Shuar tribe. These self-confident indigenous people are better known in the West under the name of the Jívaro and are stereotypically termed “the fierce people.”

In the Shuar language shamans are called uwishin. Their shamanism is traditionally characterized by rivalry and aggressive confrontations.

However, Hilario considers it necessary to collaborate with as many shamans from different South American regions as possible. His Western upbringing and his initiation into the knowledge handed down by his ancestors predestine him as an ideal figure to bridge the divide between Amazonia and the West.

Hilario Chiriap: My Shuar name is Tsunki Shiashia Churuwia. Tsunki means “gods of the waters”; Shiashia signifies the power of nature and the forest in the form of the jaguar as the guardian of knowledge; Churuwia is the name of the harpy eagle that lives high above the cliffs of the waterfalls and embodies the supreme spirit. Many waterfalls are sacred to the Shuar. Today we inhabit territory in Peru and Ecuador. Our people are divided into seven clans: Shuar, Achuar, Awagun, Kantuash, Patukmai, Wampi, and Shiwiar, who live in Ecuadorian Amazonia along the Cordilleras, the Andes, and the Río Maranon.

I was born in 1964 in the Cordillera del Cóndor, which today lies on the borders of Peru and Ecuador. Back then it was a remote region in a largely untouched jungle. I am a descendant of the Patukmai and Awagun clans; I come from a family of uwishin and was initiated as a shaman. My forefathers were warriors. My grandfathers and uncles were bound to the uwishin tradition as tsantsa (headhunters). Every clan has its own particular capabilities and harbors special secrets. As an uwishin one doesn’t necessarily know the secrets of other clans as well.

Arno Adelaars: So you only know the secret lore of your own two clans?

At first I learned the secrets of my own two clans, but later I also made contact with other clans. In the 1930s and 1940s conflict broke out among the Shuar people, and it escalated. Many significant personalities of our uwishin tradition fell victim to this tribal war. In my own family only my father survived, for example. Much of the knowledge that had been handed down was lost during this power struggle among the shamans. Many fled to other regions, and the cultural bond was broken. My father fled toward the southeast from the place where we had originally lived. He was a guardian of the traditions. Back then he passed on his knowledge to various Shuar communities throughout the entire region.

When I was five or six years old, my brother and I were initiated into the tobacco and angel’s trumpet rituals. These involve a special species of angel’s trumpet that only grows in this region. My father was a true warrior — very stern and demanding. He insisted that his sons underwent the impending trials in a disciplined manner.

Arno Adelaars: Your father was also an uwishin?

Yes — and a warrior. So he taught me how to survive. He taught me all his tricks and the art of surviving in the jungle. His instruction lasted two years. In 1970, when I was six years old, the missionaries came. They brought me, my brothers, and all the children of the surrounding area to schools that were two days’ walk from the place where we lived. My father had visions and thought: “That is good for my sons.” Until that point in time we had not known any schools. Before the missionaries came sons learned from their fathers.

I only spoke Shuar. In the following six years I learned Spanish in school and got to know something about how white people think. I had to stay in the mission school where we Indian children were treated in an inhumane manner. We weren’t allowed to speak our own language or follow our own traditions. We had to do hard physical labor in the fields, in the jungle, and in the mountains, and we were treated more or less like slaves. Today I would say it was practically like a concentration camp there. We weren’t allowed to go home. If any children managed to escape, the missionaries would send people out to capture them again, and then they would be severely punished. I spent all my time thinking over possibilities to escape that hell. And so I told the missionaries that I wanted to become a priest. They selected two children — me and another boy to go and study in Cuenca, a town in the Andes. There was a boarding school there with an atmosphere similar to that of the mission school. Nevertheless, it was more bearable there, because at least Cuenca is a town.

After I graduated at Cuenca I was approved for two years of higher education in Quito, the capital of Ecuador. Afterward I studied philosophy and psychology for some years at the Catholic University of Quito. In the meantime I was nineteen years old, and it was clear to me that I didn’t belong to the Catholic Church, to the university, or to the society of Ecuador. I had the need to follow another path in my life.

From the time I left my family and was forced to go to the mission school, I sensed a curiosity and yearning for the rituals and ceremonies of my people. Thus I sought out knowledgeable elders and shamans in various Indian communities. Many of the wise old men who had taught my father were dead by that time. So I visited regions where other clan members lived and where I had never set foot. In many of the communities that I visited I encountered conflicts, difficulties, envy, and jealousy. Some clans didn’t want to teach me. It went so far that they even sought to kill me. I had to face these threats, and we — my companion and I — armed ourselves in defense. Eventually I was able to overcome the dangers and follow the traditions in a constructive manner.

Many Shuar associate shamanism with practices that hurt other people — with negative aspects that are normally understood as brujeria or witchcraft. However, I understand shamanism as an act of healing, as something positive and as a path of light. From it I draw the power to survive and carry forward the good aspects of this shamanic tradition. I was lucky enough to find good teachers who transmitted this positive power to me. My teachers predicted that I would need four years for my training with them. Then they dismissed me. I gained their blessing and made a pledge to carry forward their tradition. Having returned home, for four years I practiced what I had learned from them.

In the early 1990s I visited other regions and found traditional lore there. I met some of my uncles and others who had known my grandfather, and who had been scattered to the four winds by the tribal conflicts of the 1930s and 1940s. They helped me to integrate some of the traditional aspects of our learning into modern times. They were aware that it was important to save them, to reconstruct them and adapt them to contemporary conditions.

I managed to establish a positive approach to traditional methods and healing practices. In retrospect I understand why I was burdened with six years in the mission school. Only in this way could I become acquainted with both worlds. Now I can convey the traditions of my Indian culture to the towns and universities; I feel at home in both worlds, and I need not fear different ways of thinking.

The Condor and the Eagle

You are concerned with the connections between diverse indigenous peoples. The encounter between the condor and the eagle is of central significance in this regard. We find ourselves in a time of upheaval.

According to the prophecy of Cuauhtémoc, the condor and the eagle will meet each other after five hundred years.

Can you go into more detail?

This prophecy comes from the Aztecs. Their ruler Cuauhtémoc prophesied that the world in which we live is the true paradise that we must preserve with the help of rituals and traditional knowledge. This prophecy comes from the north, from Mexico. Therefore the brothers of the north (the eagle) must be united with their brothers from the south (the condor).

In Quito, the capital of Ecuador, there was a meeting of indigenous peoples in December 1993. Native Americans from North and Central America met with their indigenous brothers from South America. During this meeting they exchanged their different traditions with one another. More than sixty wise elders from various regions of Ecuador were present, and more than 350 people took part in ayahuasca and peyote rituals.

Since that time I have been bound to the Indian traditions of the north by an oath and a familial, cultural, and spiritual relationship, above all with my brother Aurelio Diaz Tekpankalli. Aurelio was a leader of the Native American Church from Arizona who later emigrated to Mexico. He is the founder of the “Red Path” (Camino Rojo). In the past four years I have taken part in sun-dance ceremonies six times; I have also gone on a vision quest. In 1996 I was elected as the South American representative on the council of the Native American Church.

The police tried to stamp out this new peyote cult, as they had stamped out the ghost dance, not because peyote was a drug — drugs weren’t on our mind then — but because it was Indian, a competition to the missionaries. (Lame Deer and Erdoes 1972: 58)

There was a process of cultural and ritual exchange. I am able to perform peyote rituals of the Native American Church (NAC) that I have learned from my brother Aurelio. He introduced the use of peyote and aguakulla into the ritual. At the same time some other Shuar and I imparted our knowledge and our rituals to certain members of the NAC. Thus there is a mutual agreement that we may perform our rituals in different regions of the world.

By 1993 the time was ripe for the fulfillment of the prophecy. At that time we established these councils uniting the Indian traditions from South and North America in order to preserve rituals and lore. We strove for alliances with other ethnic groups — not only for the sake of indigenous peoples, but for the sake of all children of this Earth. We wanted to take this message to the world. Initially we were concerned with acquainting the indigenous peoples in North and South America with the various rituals, and then we sought to propagate them in other parts of the world. We were entrusted with this task by our wise old men, who were no longer capable of traveling or learning other languages. In 1997 I was invited to the south of France, where a meeting of representatives of shamanic traditions from all corners of the globe was taking place. Five hundred delegates traveled there, including the Dalai Lama. I met many shamans from Africa, Asia, Australia, and Europe.

Since then I’ve been coming to Europe every year. I’ve been invited to Germany, Spain, France, England, Italy, Austria, Slovenia, Belgium, Holland, and Switzerland. Relationships have emerged as a result. Through this crucial work people have become acquainted with our jungle medicine. They gained first impressions, deepened their insight, and eventually they wanted to know more and more about it.

For many years you have been coming to Europe and meeting some people again and again. Have you been able to detect a certain development among them?

I have noticed that people are becoming increasingly interested, and that the number of those interested is constantly growing. In the meantime some of them have a certain amount of experience with ayahuasca; I have noted that they are more seriously interested in a deeper knowledge, and that they want a more precise understanding of exactly how one may work with this medicine. They have more trust and confidence. A spark has been kindled in them, and that motivates me to return. They have recognized the value of our jungle medicine, approach the matter more seriously, and have become healthier through this experience.

What is your goal? What motivates you?

First and foremost I want to pass on our traditional teachings on the use of healing plants and “plant teachers,” in particular ayahuasca. How these plants were originally employed in Amazonia, and how they should be used. That is my central concern. In addition, I want to show people how they can mobilize their own healing powers and find a balance in their lives; how they can experience the beneficial effects of this medicine; and how they can learn to use it in the correct, traditional way. In so doing I am primarily concerned with passing on the healing power of the plants and the medicine, and ensuring that they are correctly used.

That is my mission at the moment: to transmit the practice in accordance with the instructions of my teachers who passed this task on to me. This is what is missing in people’s lives at the present time, and I must make this knowledge available to them for as long as they require it. Whether that will take ten, twenty, or thirty years, I do not know.

You are an uwishin and you work here in Europe. In what way does your work here also benefit your own people?

Here I am endeavoring to help people bring their lives into harmony. In Ecuador we are engaged in the preservation of the traditional lore. Until now this knowledge has been passed on from father to son, turning every family into a kind of school for life. This form of transmission of traditional knowledge is now threatened with extinction by the influence of schools, modern lifestyles, and migration from the country to the towns. In my homeland our work consists in making the traditional knowledge available again, in bringing it back to life and establishing it. In order to reproduce the original, traditional framework, it is necessary to cultivate the healing plants and build educational institutions in which our traditional knowledge can be transmitted.

Nevertheless, the positive results that have been achieved — be it in Europe or in Ecuador — are relatively similar. I want to create contacts between Europeans and my fellow citizens and promote mutual exchange. It would be great if journeys to Ecuador could be organized in Europe in order to establish spiritual and emotional contacts, which would promote a deeper understanding for the needs and problems of Ecuador. The capitalist encroachment and the economic interest in the exploitation of natural resources and the promotion of oil present a real and serious problem. Although my people are numerous, ultimately they are in the minority. We are subject to a constant threat, and so it is good for us to have advocates and allies in the West.

What ideas do you have for the future in this regard?

That is a very important topic for us. In 2002, four representatives of the Shuar who had vehemently resisted the interests of the mining and oil companies were killed in a plane crash that remains unexplained.

I am well aware of the extent of this problem. Nevertheless, things transpire on both the material and the spiritual planes. A fragile equilibrium exists between the two; if this equilibrium is lost, it is possible that terrible consequences will result. Perhaps the spiritual plane manifests itself in this way… We understand the principles of Realpolitik. Power politics makes use of these forces in order to achieve its aims. We are well aware of this.

Our culture is based upon martial principles. But today we are no longer warriors. Instead we employ our martial experience to develop an astute understanding of the goals of our opponents, and to open up our spirit to how these are manifested on the spiritual plane. If that fails, then we accept whatever happens — even when that means that our land must be delivered up to impending developments.

In this decade we find ourselves in the midst of a phase of turmoil. War is omnipresent. We must accept the spirit of the time. Currently the material powers are gaining the upper hand. Yet we are also experiencing the culmination of this process. You could compare it to a sick body. Mother Earth is sick. She is suffering from a fever and must vomit and cleanse herself. Her whole body is wracked with fever and at a given time it must throw up and be purified. I am speaking here of a comprehensive cleansing and purifying process, which we are all passing through at this point in time. The spirit recognizes where people are to be found who respect the Earth and accept her as their mother. A new power will emanate from these places. Every single one of us must surrender ourselves to the obligation of restoring the equilibrium of powers and respecting Mother Earth.

Vigorous efforts to restore the traditions and integrate them into our lives are currently underway. Without these efforts it would all be futile. The restoration of the true work is important. In Colombia there are shamans who cooperate with the guerrillas; others have joined the army. In Ecuador the leaders of indigenous tribes have been recruited as representatives of various mining and oil companies, and they have been used in those companies’ interests.

However, those who follow the true shamanic path, and who sing the traditional songs together with others in honor of the mystery of the Earth — they cannot be recruited. It is important that this recovery process is implemented as quickly as possible, and with the help of as many shamans who follow the traditional path — and not its perversion — as possible. It is very important to revive the traditions, because there is quite some confusion prevailing with regard to them.

This work is very complex, as there are many different traditions. Anyone who takes the vow will follow it for their entire life. That involves many different facets, not only ayahuasca and the healing traditions. It is substantially more complex. You must approach the entire matter step by step.

The Making of a Shuar Shaman

How do you become an uwishin? You mentioned that you spent four years in the mountains. In Europe there are no longer any living shamanic traditions. Nevertheless, many people feel attracted by them. There are many among us who call themselves shamans. Can you give us some insight into your initiation?

Traditionally you went to an uwishin from whom you wished to learn and asked him for his instructions. If he accepted the pupil he would develop a special training program for him. He gave him certain tasks that he had to fulfill unconditionally. In earlier times, when the training followed universally binding rules, the initiation took place at special places in traditional malocas. Three separate rooms were specially constructed for the training period: one for healings, one for the training, and one spiritual site reserved for the retreat of a shaman’s apprentice. These days there aren’t many of these left, because now it’s all about competition, money, and individuality. For that reason a shaman’s apprentice simply lives in the household of the uwishin.

The first phase of the training is dedicated to the sharpening of the senses at a secluded site, where you spend seven, nine, or even thirteen days in silence. During this period you fast, without food and without water. In the following three months communication with other people is limited to what is absolutely essential. In this phase of silence you primarily sharpen the faculty of hearing and — secondarily — the faculty of sight. During the training period sexual abstinence is very important. It promotes inner awareness, which is easier when you are in close proximity to the teacher. I spent four years in this state of seclusion, although twelve to fifteen months is more common. Today some people even consider a period of fourteen days to be sufficient… Three months is better and six months is customary. But in my case it was in fact four years. We are speaking here of a holistic invigoration of the spirit, the body, and the spiritual energy that manifests itself physically.

Depending on the teacher, there are also specific dietary regulations concerning foodstuffs that may or may not be consumed. Some forbid every kind of meat, others prohibit particular animal foods. No pork and monkey meat, for example, or only bird flesh, or only fish and mussels. What you may or may not eat depends on the individual teacher. Other common diets prohibit salt, sugar, coffee, tea, and cheese. The duration of such restrictions is quite variable. Some last for one, two, or three months; others a few weeks or a whole year — this too is decided upon by each individual teacher.

This spiritual training also involves the cultivation of particular behavior patterns and abilities: exercising patience, for example, and remaining calm. During my four-year basic training I often thought to myself: “What am I actually doing here?” Again and again, doubts emerged. But then I heard an inner voice that whispered to me: “You are in the right place. Just keep going — follow your path, just keep going.” I was plagued by intense doubts for two months long. Then I thought to myself: “If hundreds and thousands of people have followed this path and have survived it, there must be something real hidden on this path of knowledge, and I must continue on it and break through to this truth.” For most of my fellow apprentices this inner power was not strong enough, and they succumbed to the craving of sexual lust or other distractions. They said to themselves: “What is the point in spending my time here? I should be earning money or going to school instead.”

The goal of this learning process is acquaintance with subtle energies. But you learn this in a very practical and empirical way, based upon concrete experiences. You learn the songs and the force that lies within them. You practice making contact with the spirit world, and in the invisible world you gain access to the animals. You learn how to hunt them and how to locate them. You also learn to build houses, which is very practical. But the most important goal is to come into contact with the subtle energies of the true knowledge.

A shaman enjoys a certain social prestige. For this reason some people are very eager to call themselves shamans. They watch how I lead my ceremonies, sing songs, and play my instruments. It all seems very easy to them. They don’t see the hard side of this path. However, you can’t take a “holiday” from this path when the going gets tough. You must follow it relentlessly. This path never ends. It goes on forever.

Hilario, many thanks for your vivid insights into the life and career of an uwishin.

***